These ancient Jewish texts from the Second Temple era are known as the Dead Sea Scrolls, or Qumran Cave Scrolls. They were found at the Qumran Caves close to Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the northern coast of the Dead Sea, over a ten-year period between 1946 and 1956. The Dead Sea Scrolls are the oldest extant manuscripts of whole books that were eventually added to the biblical canon. They also contain extra-biblical and deuterocanonical writings from late Second Temple Judaism, and they date from the third century BCE to the first century CE. They also provided fresh insight into the rise of Rabbinic Judaism and Christianity.

Nearly all of the 15,000 scrolls and scroll fragments are kept in the Israel Museum’s Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem. The Dead Sea Scrolls were mostly discovered after Jordan annexated the West Bank and were acquired by Israel after Jordan lost the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Jordan and the Palestinian Authority dispute the Israeli government’s custody of the scrolls on territorial, legal, and humanitarian grounds, while Israel’s claims are primarily based on historical and religious grounds, given their significance in Jewish history and in the heritage of Judaism.

In the Dead Sea region, many thousands of writing pieces have been found. Most of them include just fragments of text and are the remains of bigger manuscripts that were destroyed either naturally or by human intervention. Less than a dozen manuscripts from the Qumran Caves are among the few that have survived, all of which are almost entirely complete and in excellent condition. Discovered between 1946/1947 and 1956, 11 caves in the immediate area of the Hellenistic Jewish community at the site of Khirbet Qumran in the eastern Judaean Desert of the West Bank have yielded a collection of 981 distinct scrolls that researchers have compiled.

The scrolls’ name comes from the location of the caverns, which are around 1.5 kilometers (1 mile) west of the Dead Sea’s northwest shore. The ancient Jewish sect known as the Essenes has long been linked to the scrolls by archaeologists; however, some more modern interpretations cast doubt on this relationship, claiming that the scrolls were written by Jerusalem priests or other unidentified Jewish organizations.

The majority of the manuscripts are written in Hebrew, while a small number are written in Greek, Aramaic (such as the Son of God Text), and several regional dialects, including Nabataean. Arabic (from Khirbet al-Mird) and Latin (from Masada) discoveries have been made in the Judaean Desert. The texts are written on parchment for the most part, papyrus for some, and metal for some. There are texts from related Judaean Desert locations that date between the eighth and eleventh centuries BCE, despite scholarly agreement dating the Dead Sea Scrolls to between the third and first centuries BCE.

Paleography and radiocarbon dating of the scrolls are supported by a sequence of bronze coins discovered at the same places. The series starts with John Hyrcanus, a Hasmonean Kingdom monarch (in office 135–104 BCE), and goes until the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE).

Researchers have not recognized all of the scrolls’ texts due to their poor state. Three broad categories may be made out of the identified texts:

- literature from Hebrew scriptures make up almost 40% of the literature.

- Thirty percent of the books are from the Second Temple era and were eventually excluded from the Hebrew Bible canon. Some examples of these texts include the Wisdom of Sirach, the Book of Enoch, the Book of Jubilees, the Book of Tobit, and Psalms 152–155.

- The remaining portion (approximately thirty percent) consists of sectarian manuscripts of previously undiscovered texts that clarify the laws and doctrines of a certain sect or sect within the larger Jewish community. Examples of these texts include the Rule of the Blessing, the War Scroll, the Community Rule, and the Pesher on Habakkuk.

Finding out

Between 1946 and 1956, Bedouin shepherds and a group of archaeologists found the Dead Sea Scrolls in a group of 12 caves surrounding the location that was once known as Ein Feshkha close to the Dead Sea in the West Bank (which was then under Jordanian authority). Genizah, an old Jewish ritual, refers to the practice of keeping worn-out sacred scrolls in earthenware containers buried in the ground or inside caves.

Initial discovery (1946–1947)

Between November 1946 and February 1947, Bedouin shepherd Muhammed edh-Dhib, his cousin Jum’a Muhammad, and Khalil Musa made the first find. In a cave close to the present-day Qumran site, the shepherds found seven scrolls (see § The Caves and their scrolls and fragments) preserved in jars. Based on many conversations with the Bedouins, John C. Trever pieced together the account of the scrolls. Although Edh-Dhib’s cousin was aware of the caverns, Edh-Dhib was the first to tumble into one (today known as Cave 1). He brought a few scrolls back to the camp to show his family, which Trever recognizes as the Community Rule, the Habakkuk Commentary, and the Isaiah Scroll.

In the process, none of the scrolls were damaged. The Bedouins displayed the scrolls to their people on occasion while they debated what to do with them. They kept the scrolls hanging on a tent pole. The Community Rule was divided into two halves at some point during this period. After being informed that the scrolls could have been taken from a synagogue, the Bedouins initially brought them to a merchant in Bethlehem called Ibrahim ‘Ijha. ‘Ijha returned the scrolls, declaring them to be worthless. Despite their fear, the Bedouins proceeded to a local market where a Christian Syrian offered to purchase them. They were talking when a sheikh entered the room and advised them to take the scrolls to Khalil Eskander Shahin, well known as “Kando,” a cobbler and occasional antiquities dealer.

Trever of the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) became interested in the original seven scrolls in 1947. He discovered parallels between the scrolls’ script and the earliest known bible document at the time, the Nash Papyrus. Due to the Arab-Israeli War in March 1948, some of the scrolls had to be moved to Beirut, Lebanon, for protection. Head of the ASOR Millar Burrows made the scroll finding public in a news statement on April 11, 1948.

Qumran cave exploration (1948–1949)

Professor Ovid R. Sellers, the ASOR’s successor, received some more scroll fragments that Metropolitan Bishop Mar Samuel had obtained early in September 1948. By 1948’s end, almost two years after the scrolls were discovered, researchers still hadn’t been able to find the original cave where the fragments had been discovered.

It was unsafe to conduct a large-scale search at that time due to the upheaval in the nation. The Syrians were persuaded by sellers to help in the cave search, but they could not afford their terms. The Arab Legion was given authorization by the Jordanian government to conduct a search in the region where the original Qumran cave was said to be located at the beginning of 1949.

As a result, on January 28, 1949, Arab Legion captain Akkash el-Zebn and Belgian United Nations observer captain Phillipe Lippens made a new discovery of Cave 1.

Qumran caves rediscovery and new scroll discoveries (1949–1951)

The Jordanian Department of Antiquities, under the direction of Gerald Lankester Harding and Roland de Vaux, conducted the first excavation of the site from February 15 to March 5, 1949, in response to the discoveries of what is now known as Cave 1 at Qumran. More pieces of the Dead Sea Scroll, linen, jars, and other artifacts were found at the Cave 1 site.

Excavations of Qumran and new cave discoveries (1951–1956, 2017, 2021)

De Vaux and his ASOR team started a thorough excavation of Qumran in November 1951. The Bedouins found thirty fragments in what was to become Cave 2 by February 1952. After a second cave was found, 300 fragments from 33 manuscripts were found, including Hebrew-language portions of the Wisdom of Sirach and Jubilees. On March 14, 1952, the ASOR team uncovered a third cave containing pieces of the Copper Scroll and Jubilees the following month. The ASOR crews found the remains and scrolls of Caves 4, 5, and 6 between September and December of 1952.

The Bedouins and the ASOR archaeologists intensified their respective searches for the scrolls in the same approximate region of Qumran, which was more than one kilometer in length, as the monetary worth of the scrolls increased as their historical significance became more widely known. De Vaux oversaw four further archaeological digs in the region between 1953 and 1956 in order to unearth scrolls and artifacts. The final pieces to be unearthed in the area around Qumran were located in Cave 11, which was uncovered in 1956.

Caves 1, 2, 3, and 11 are situated one mile (two kilometers) north of Khirbet Qumran, with Cave 3 being the most isolated. Caves 4–10 are grouped together in an area that is comparatively close to Khirbet Qumran, around 150 meters (160 yards). Archaeologists from Hebrew University declared in February 2017 that they had found a new cave, the 12th. One blank parchment was discovered in a jar, but pickaxes, shattered and empty scroll jars and other items point to the cave having been plundered in the 1950s.

Israeli archaeologists revealed in March 2021 that they had found scores of fragments from the Greek-written volumes of Zechariah and Nahum that included biblical text. This collection of artifacts is said to have been stashed away during the Bar Kokhba uprising in a cave between 132 and 136 CE. However, at the Muraba’at caverns in the Nahal Darga Reserve, a 10,500-year-old braided reed basket was also found. A stockpile of coins from the Bar Kochba uprising and the remains of a kid wrapped in cloth, dating to around 6,000 years ago, were among the other findings. Additional scrolls were found in 2021 by Israeli officials at the Cave of Horrors, a different cave close to the Dead Sea.

Origin

The origin of the Dead Sea Scrolls has been the subject of great discussion. The prevalent belief that the scrolls were created by the Essenes, a Jewish group that lived close to Qumran, is still in place, although a number of contemporary researchers have begun to question this view.

Qumran–Sectarian theory

Variations on the Qumran-Essene idea are known as Qumran-Sectarian theories. The fundamental point of divergence from the Quran–Esene idea is the reticence of linking the Dead Sea Scrolls, especially with the Essenes. The majority of supporters of the Qumran-Sectarian theory assert that the Dead Sea Scrolls were created by a group of Jews who lived at or close to Qumran, albeit they do not necessarily draw the conclusion that these individuals were Essenes.

A particular variant of the Qumran-Sectarian idea that first surfaced in the 1990s and has been increasingly well-known recently is the theory put out by Lawrence H. Schiffman, who suggests that a group of Zadokite priests (Sadducees) governed the community. The “Miqsat Ma’ase Ha-Torah” (4QMMT), which lists purity restrictions (such as the transfer of contaminants) comparable to those attributed to the Sadducees in rabbinic sources, is the most significant document supporting this position. Additionally, 4QMMT replicates a festival calendar that dates certain festival days according to Sadducee principles.

Christian origin theory

In the 1960s, José O’Callaghan Martínez, a Spanish Jesuit, contended that one fragment (7Q5) retains a passage from the New Testament Gospel of Mark 6:52–53. A paleobotanical investigation of the specific piece examined this idea in 2000. However there was significant disagreement over this, and O’Callaghan’s idea is still up for debate. O’Callaghan’s initial claim was supported by further analyses conducted in 2004 and 2018.

The idea that certain scrolls describe the early Christian society has been furthered by Robert Eisenman. Additionally, Eisenman contends that the events documented in some of these writings line up with the lives of Paul the Apostle and James the Just.

Jerusalem origin theory

Some academics have suggested that the scrolls originated from Jews who lived in Jerusalem and secreted them in caves close to the Qumran while escaping the Romans after Jerusalem’s destruction in 70 CE. The idea that the Dead Sea Scrolls originated in the Jerusalem library of the Jewish Temple was initially put out by Karl Heinrich Rengstorf in the 1960s.

Afterward, Norman Golb proposed that the scrolls might not have come from the Jerusalem Temple library alone, but rather from a number of libraries in Jerusalem. The differences in writing and style among the scrolls, according to proponents of the Jerusalem origin argument, disprove the idea that the scrolls originated at the Qumran.

A number of archaeologists, such as Yizhar Hirschfeld and, more recently, Yizhak Magen and Yuval Peleg, have acknowledged that the scrolls’ origin is not Qumran. They all believe that the remnants of Qumran are those of a Hasmonean fort that was repurposed at a later time.

Physical characteristics

Radiocarbon dating

Numerous Dead Sea Scrolls’ parchment has undergone carbon dating. In 1950, a piece of linen from one of the caves was used for the first test. This examination ruled out early theories linking the scrolls to the Middle Ages, providing an indicative date of 33 CE plus or minus 200 years. Two extensive sets of examinations have been conducted on the scrolls since then. VanderKam and Flint provided a summary of the findings, stating that there is “a strong reason for thinking that most of the Qumran manuscripts belong to the last two centuries BCE and the first century CE.”

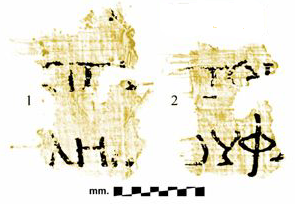

Paleographic dating

Numerous experts in the area have examined the writings of the Dead Sea Scrolls through the lens of paleography, or the analysis of letter formations. According to a thorough linguistic examination, the pieces date between 225 BCE and 50 CE. The text’s size, variety, and style were all taken into consideration while determining these dates. Later, the same fragments were analyzed using radiocarbon dating, yielding an estimated 68% accuracy rate and a dating range of 385 BCE to 82 CE.

Ink and parchment

The University of California, Davis used a cyclotron to analyze the scrolls and discovered that all of the black ink was carbon black. Cinnabar (mercury sulfide, or HgS) was discovered to be the source of the red ink on the scrolls. Throughout the whole collection of pieces from the Dead Sea Scroll, this red ink is only used four times.

Most of the black ink on the scrolls is carbon soot from lamps lit with olive oil. In order to dilute the ink to the right consistency for writing, ingredients including honey, oil, vinegar, and water were commonly added to the concoction. Occasionally, galls were added to the ink to increase its durability. Its writers utilized reed pens to put the ink to the scrolls.

Around 85.5–90.5% of the Dead Sea Scrolls were written on parchment produced from processed animal skin, known as vellum; around 8–13% were written on papyrus; and approximately 1.5% of the scrolls were written on sheets of bronze consisting of roughly 99% copper and 1% tin.

By using DNA testing for assembly reasons, academics with the Israeli Antiquities Authority (IAA) think that there may be a hierarchy in the religious worth of those scrolls written on animal skins based on which kind of animal was used to manufacture the hide. Scholars believe that scrolls written on goat and calf hides have greater religious significance in nature, but scrolls written on gazelles or ibex hides are thought to have less religious significance.

By using X-ray and particle-induced X-ray emission testing of the water used to make the parchment and comparing it with the water from the area around Qumran, tests conducted by the National Institute of Nuclear Physics in Sicily have suggested that the origin of parchment of select Dead Sea Scroll fragments is from the Qumran area.

Biblical significance

The oldest Hebrew-language Bible manuscripts before the Dead Sea Scrolls were found were Masoretic writings from the 10th century CE, such as the Aleppo Codex. The earliest Masoretic Text manuscripts that are currently in existence are thought to have been written in the ninth century. The biblical writings discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls are dated to the second century BCE, which is more than a millennium ago. For Old Testament academics, this was a major finding, as they had assumed that the Dead Sea Scrolls would support or contradict the validity of textual transmission from the original texts to the earliest available Masoretic texts.

The discovery showed that the extraordinary fidelity of transmission across a millennium made it fair to assume that the texts of the Old Testament that are in use today are accurate reproductions of the original writings.

According to The Dead Sea Scrolls by Hebrew scholar Millar Burrows

Of the 166 words in Isaiah 53, there are only seventeen letters in question. Ten of these letters are simply a matter of spelling, which does not affect the sense. Four more letters are minor stylistic changes, such as conjunctions. The remaining three letters comprise the word “light,” which is added in verse 11, and does not affect the meaning greatly.

Variations were seen between text segments. The Oxford Companion to Archaeology states that:

- Some biblical manuscripts from the Qumran show striking changes in language and substance from the Masoretic, or conventional, Hebrew text of the Old Testament, whereas other manuscripts from the books of Exodus and Samuel discovered in Cave Four are almost exactly the same. The biblical discoveries from the Qumran, with their astounding variety of textual variations, have forced scholars to reevaluate the long-held beliefs about how the modern biblical text developed from just three manuscript families: the Masoretic text, the Hebrew original of the Septuagint, and the Samaritan Pentateuch. It is becoming more and more obvious that the Old Testament was very ambiguous prior to its canonization in the year 100 A.D.

A consensus has emerged that many of the texts discovered are not biblical in nature and were considered unimportant for comprehending the composition or canonization of the biblical books. However, many of these texts are believed to have been collected rather than composed by the Essene community. It is currently acknowledged by scholars that a portion of these writings were created before the Essene period, while the biblical books were still being written or redacted into final form.

Biblical books found

The manuscripts found in the Dead Sea Scrolls contain 225 biblical scriptures, or around 22% of the whole canon, together with 10 deuterocanonical books. Parts of every book in the Hebrew Bible’s Tanakh and the Old Testament proto-canon are found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, with the exception of one. They also contain Tobit, Sirach, Baruch 6 (sometimes called the Letter or Epistle of Jeremiah), and Psalm 151, four of the deuterocanonical writings found in Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Bibles.

Scholars speculate that the reason the Book of Esther has not been discovered yet is either because the book contains the Purim celebration, which is not observed in the Qumran calendar, or because Esther is a Jew whose marriage to a Persian monarch may have been frowned upon by the people of Qumran.

The Bible’s most often represented books among the Dead Sea Scrolls are listed below, along with the deuterocanonical. The number of Dead Sea texts that can be translated into other languages and represent a copy of each biblical book is also provided.

| Book | Number found |

|---|---|

| Psalms | 39 |

| Deuteronomy | 33 |

| 1 Enoch | 25 |

| Genesis | 24 |

| Isaiah | 22 |

| Jubilees | 21 |

| Exodus | 18 |

| Leviticus | 17 |

| Numbers | 11 |

| Minor Prophets | 10 |

| Daniel | 8 |

| Jeremiah | 6 |

| Ezekiel | 6 |

| Job | 6 |

| Tobit | 5 |

| Kings | 4 |

| Samuel | 4 |

| Judges | 4 |

| Song of Songs (Canticles) | 4 |

| Ruth | 4 |

| Lamentations | 4 |

| Sirach | 3 |

| Ecclesiastes | 2 |

| Joshua | 2 |

Facts about the Dead Sea Scrolls

- The Dead Sea Scrolls discovered between 1947 and 1956 in the Judean Desert, are a collection of ancient Jewish texts that provide critical insights into Second Temple Judaism.

- They are considered one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of the 20th century, shedding light on both religious practices and historical events from over two thousand years ago.

- The scrolls were found in eleven caves near the site of Qumran, located on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea in what is now Israel.

- Written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, the texts include fragments from the Hebrew Bible, as well as non-canonical and sectarian writings.

- The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls revolutionized our understanding of the development of the Hebrew Bible and the origins of early Jewish sects, particularly the Essenes.

- Scholars believe the Essenes, a Jewish sect known for their ascetic lifestyle, were likely responsible for the preservation of many of the scrolls found in Qumran.

- Among the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Isaiah Scroll is the only nearly complete copy of the Book of Isaiah, dating back to around the 2nd century BCE.

- The Great Isaiah Scroll is particularly significant because it is over 1,000 years older than the previously known oldest manuscripts of Isaiah, demonstrating the accuracy of biblical transmission.

- The scrolls contain a range of literary genres, including biblical texts, commentaries, hymns, legal documents, and apocalyptic literature.

- Over 900 manuscripts have been identified from the Dead Sea Scrolls, though most are in fragmentary form, with some comprising just tiny pieces of parchment or papyrus.

- The scrolls are believed to date from around 200 BCE to 70 CE, during a turbulent period in Jewish history, including the Hasmonean and Herodian periods.

- The discovery was initiated by Bedouin shepherds, who stumbled upon the first set of scrolls in Cave 1 near Qumran, prompting further archaeological exploration.

- Many of the scrolls were written on parchment made from animal skins, while others were penned on papyrus, an early form of paper made from the papyrus plant.

- The texts offer a rare glimpse into the diversity of Jewish religious thought during the Second Temple period, including beliefs about the Messiah, ritual purity, and angels.

- Some scrolls include writings that were not accepted into the Jewish canon or later Christian Old Testament, such as the Book of Jubilees and the Book of Enoch.

- The Dead Sea Scrolls feature several examples of the Pesher method of biblical interpretation, where the writers applied prophetic passages to their own time and community.

- In addition to religious texts, the scrolls include community rules, such as the Community Rule, which describes the structure and regulations of the Qumran sect.

- One of the most famous scrolls is the War Scroll, which details a future apocalyptic battle between the “sons of light” and the “sons of darkness.”

- The Copper Scroll, found in Cave 3, is unique because it was written on metal and lists hidden treasures, though none of these treasures have ever been found.

- The Temple Scroll, one of the longest scrolls, contains detailed descriptions of an idealized Temple and its rituals, believed to reflect the Qumran community’s vision of a future Jerusalem.

- Carbon-14 dating and paleographic analysis have been used to date the scrolls, confirming their authenticity and providing a timeline of Jewish thought during the Second Temple era.

- The texts show evidence of conflict and tension between various Jewish sects, including disagreements over the correct calendar and observance of Jewish law.

- The Qumran community, thought to be responsible for many of the scrolls, lived a life of extreme piety and ritual purity, possibly in anticipation of an imminent end times.

- Essenes, a Jewish sect contemporaneous with the Pharisees and Sadducees, are often associated with the Qumran sect due to the lifestyle described in the scrolls.

- The Damascus Document, found in both the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Cairo Geniza, provides rules and regulations for the Qumran community and sheds light on their social structure.

- Many scholars believe that the Essenes retreated to Qumran to escape the Hellenistic influences and corruption they saw in Jerusalem and the Temple.

- The discovery of the scrolls also contributed to our understanding of the sectarianism that was present in early Judaism, prior to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE.

- Physical preservation of the scrolls has been a major challenge, with some scrolls suffering from decay due to exposure to light, humidity, and mishandling after their initial discovery.

- In 1967, after the Six-Day War, Israel gained control of the Qumran caves and the scrolls, which had previously been in the hands of the Jordanian Department of Antiquities.

- The Israel Museum in Jerusalem now houses the majority of the Dead Sea Scrolls, where they are preserved in the Shrine of the Book, a building designed specifically for their display.

- The scrolls have been the subject of much scholarly debate, particularly concerning the identity of their authors, with some scholars arguing that multiple Jewish sects contributed to the collection.

- The publication of the scrolls was delayed for many years due to the limited number of scholars who had access to them, creating controversy over the slow pace of academic research.

- In the 1990s, access to the scrolls was democratized, and high-resolution photographs of the scrolls were made available to researchers worldwide.

- Some of the Dead Sea Scrolls provide the earliest known versions of certain biblical books, such as Deuteronomy, Psalms, and Isaiah, making them invaluable for textual criticism.

- The scrolls also reveal that there was no single authoritative version of the Hebrew Bible in antiquity, as multiple textual traditions existed side by side.

- The sectarian scrolls suggest that the Qumran community followed a solar calendar, in contrast to the lunar-solar calendar used in the Jerusalem Temple.

- The texts found in Cave 4 represent the largest cache of manuscripts, comprising about 75% of all Dead Sea Scrolls fragments.

- Scholarly consensus places the origin of the scrolls within the Second Temple period, although the exact dates and provenance of some manuscripts remain a matter of debate.

- The Dead Sea Scrolls have also attracted interest from Christian scholars, as they provide historical context for understanding the environment in which early Christianity emerged.

- Several scrolls allude to an anticipated Messianic figure, reflecting the diversity of messianic expectations in Jewish thought during the Second Temple period.

- The scrolls were hidden in caves during a time of great upheaval, likely around the time of the First Jewish-Roman War (66-73 CE), to protect them from Roman forces.

- Scroll jars, pottery vessels designed to store and protect the scrolls, were found in several of the caves, including Cave 1, where the first scrolls were discovered.

- Many of the scrolls exhibit scribal errors, corrections, and marginal notes, providing insight into the scribal practices and the transmission of biblical texts during antiquity.

- The Orthodox Jewish community, while acknowledging the historical importance of the scrolls, has been cautious about their religious significance due to their non-canonical content.

- The Psalms Scroll contains over 35 psalms, many of which are similar to those found in the Masoretic Text, while some are previously unknown compositions.

- New digital technologies, such as multispectral imaging, have allowed scholars to read previously illegible fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls, unlocking new insights.

- In 2021, new fragments of the scrolls were found in Cave of Horror, marking the first significant Dead Sea Scroll discovery in over 60 years.

- The scrolls provide critical insights into the ritual purity laws, especially concerning bathing and purification rites, as practiced by the Qumran community.

- Some fragments of the scrolls suggest a dualistic worldview, where the forces of good and evil are in constant conflict, a theme prevalent in apocalyptic literature.

- Today, the Dead Sea Scrolls are recognized as one of the most important sources of information for understanding the development of Judaism and Christianity during the Second Temple period.