In the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra, India (today known as the Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district), are the Ellora Caves, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. One of the biggest systems of rock-cut Hindu temple caves in the world, it has multiple Buddhist and Jain “caves” as well as artwork from the 600–1000 CE era. Several of the structures in the complex—which is a premier example of Indian rock-cut architecture—are not exactly “caves” since they lack roofs.

Cave 16 is home to the Kailash temple, a chariot-shaped monument devoted to the deity Shiva and the biggest single monolithic rock excavation in the world. Along with relief panels that summarize the two main Hindu epics, the Kailash temple excavation includes statues of different Hindu deities.

34 of the site’s more than 100 caverns are accessible to the public; the others were all dug out of the Charanandri Hills’ basalt cliffs. These include five Jain (caves 30-34), twelve Buddhist (caves 1- 12), and seventeen Hindu (caves 13–29) caves. Each set of caves represents myths and deities that were common in the first century CE, together with monasteries of that faith. Because of their proximity to one another, they serve as an example of the religious coexistence of ancient India.

The Rashtrakuta dynasty (r. 753-982 CE) erected some of the Hindu and Buddhist caves, while the Yadava dynasty (c. 1187–1317) built many of the Jain caves. Together, these dynasties are responsible for the construction of all the Ellora monuments. Rich locals, traders, and royalty all contributed money to the monuments’ construction.

A major economic hub in the Deccan, the site was situated on a historic South Asian trade route, even though the caverns were used as shrines and a place for pilgrims to relax. It is around 300 kilometers (190 miles) east-northeast of Mumbai and 29 kilometers (18 miles) north-west of Aurangabad.

The Ellora Caves and the neighboring Ajanta Caves are now popular tourist destinations in Maharashtra’s Marathwada area, and the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has designated them as protected monuments.

Meaning and Origin

The ancient name Elloorpuram was shortened to Ellora, also known as Verul or Elura. The name’s earlier version may be found in historical references, such as the Baroda inscription from 812 CE, which speaks of “the greatness of this edifice” and states that Krishnaraja erected the Kailasa temple, a large edifice, on a hill in Elapura. Every cave in India is given a name along with the suffix Guha (Sanskrit), Lena (Marathi), or Leni (Sanskrit), which means “cave.”

Ilvalapuram, named after the asura Ilvala who dominated this region until being defeated by Sage Agastya, is another place it is said to have originated.

Place

Approximately 29 kilometers (18 miles) northwest of Sambhaji Nagar, 300 kilometers (190 miles) east-northeast of Mumbai, 235 kilometers (146 miles) from Pune, approximately 100 kilometers (62 miles) west of the Ajanta Caves, and 2.3 kilometers (1.42 miles) from Grishneshwar Temple are the locations of the Ellora Caves in the state of Maharashtra.

Ellora is located in the Western Ghats in a comparatively level and rugged area where prehistoric volcanic activity produced the Deccan Traps, layered basalt structures. During the Cretaceous epoch, volcanic activity created the west-facing cliff that is home to the Ellora caves.

Because of the resulting vertical face, builders were able to more easily reach several strata of rock formations and select basalt with finer grains for intricate sculpture.

Timeline

Since the British colonial era, scholars have researched the Ellora structure. However, it has proven challenging to come to a consensus on the order in which the Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain caves were constructed due to their shared designs. Generally speaking, the arguments center on two issues: first, whether caves—Buddhist or Hindu—were carved first, and second, when caves within a certain tradition should be dated.

Based on a comparison of Ellora’s carving styles with other dated cave temples in the Deccan, textual records from different dynasties, and epigraphical evidence from several archaeological sites in Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, and Karnataka, a broad consensus has been reached.

Three significant building eras are said to have occurred at the Ellora caves, according to Geri Hockfield Malandra and other academics [who?]: an early Hindu period (~550 to 600 CE), a Buddhist phase (~600 to 730 CE), and a later Hindu and Jain phase (~730 to 950 CE).

The Traikutaka and Vakataka dynasties—the latter of which is credited with funding the Ajanta caves—may have been the architects of the first caverns. Nonetheless, it is thought likely that the Chalukya dynasty constructed the Buddhist caves, while the Shiva-inspired Kalachuri dynasty constructed some of the oldest caves, including Hindu Cave 29.

The Rashtrakuta dynasty constructed the early Jain and later Hindu caves, while the Yadava dynasty—which had previously funded the construction of other Jain cave temples—built the final Jain caves.

Hindu monuments: 13–29 Caves

The Hindu caves were built in two stages between the middle of the sixth and the end of the eighth centuries, during the Kalachuri era. Early in the sixth century, nine cave temples were excavated, and then four more caves (caves 17–29). Prioritizing the excavation of Caves 28, 27, and 19, work also began on Caves 29 and 21, which were dug out alongside Caves 20 and 26. The final two caves to be initiated were 17 and 28.

The subsequent caverns, numbered 14, 15, and 16, were built in the Rashtrakuta era; some of them belong to the eighth or tenth century. First, work was done in Caves 14 and 15, with Cave 16, the biggest monolith in the world, being the last of the three to be built. With the help of King Krishna I, these caverns were finished in the eighth century.

Ancient Hindu temples: Cave 29 and Dhumar Lena

Before any of the Buddhist or Jain caves, construction began in the early Hindu caves. The Hindu god Shiva was often the subject of these prehistoric cave paintings, but it appears from the iconography that the artists also accorded prominence and respect to other Hindu gods and goddesses. These cave temples were all characterized by a centrally located, rock-cut linga-yoni encircled by a path for circumambulation (parikrama).

One of the largest and oldest excavations in Ellora is Cave 29, also known as Dhumar Lena. A natural waterfall called “Vale Ganga” served as the focal point of the early Hindu temple construction in the cave, which was incorporated into the structure. The waterfall, which may be seen from a balcony with rock carvings to the south, is said to be “falling over great Shiva’s brow” in the monsoon season.

The author Dhavalikar claims that although the sculptures in this cave are greater than life size, they are “corpulent, stumpy with disproportionate limbs” in comparison to the engravings in other Ellora caves.

Cave 21 at the Rameshwar Temple

Another ancient excavation, Cave 21, also known as Rameshwar Lena, is said to have been built during the Kalachuri dynasty. The cave was finished before the Rashtrakuta dynasty rose to power and expanded the Ellora cave system.

While there are certain works in the cave that are identical to those in other Ellora caves, there are also other pieces that are unique, such as those that tell the narrative of goddess Parvati’s pursuit of Shiva. Other caverns have carvings that show Parvati and Shiva relaxing, Parvati’s marriage to Shiva, Shiva dancing, and Kartikeya (Skanda).

The Sapta Matrika, the seven mother goddesses of the Hindu Shakti tradition, are also prominently displayed in the cave, with Shiva and Ganesha on either side. Other deities revered in Shakti tradition may be found within the temple, such as the Durga.

Large statues of the goddesses Ganga and Yamuna, which stand in for the two main Himalayan rivers and their cultural significance in India, flank the entrance to Cave 21.

The mandapa square concept governs the cave’s symmetrical layout, which features imbedded geometric patterns that are replicated all over the place. Situated in an equilateral triangle, the Shiva linga at the temple’s sanctum sanctorum is equally spaced from the two largest sculptures of the goddesses Yamuna and Ganga.

Carmel Berkson says that this arrangement probably represents the basic Hindu theological concept of the Brahman–Prakriti connection, which is the interdependence of the male and feminine forces.

The Kailāśa temple: Cave 16

The Kailasa temple, also known as Cave 16, is a particularly famous cave temple in India because of its grandeur, construction, and the fact that it is completely carved out of a single rock.

Shiva is the subject of the Kailasha temple, which drew inspiration from Mount Kailasha. Its architecture is reminiscent of other Hindu temples, featuring an assembly hall, a gateway, a multi-story main temple encircled by multiple shrines arranged in squares, an integrated circumambulation area, a garbha-grihya (sanctum sanctorum) housing the linga-yoni, and a spire-shaped like Mount Kailash, all carved from a single rock.

In addition to the ten avatars of Vishnu, the Vedic gods and goddesses Indra, Agni, Vayu, Surya, and Usha, as well as non-Vedic deities like Ganesha, Ardhanarishvara (half Shiva, half Parvati), Harihara (half Shiva, half Vishnu), Annapurna, Durga, and others, are all honored in other shrines carved from the same rock.

Numerous Shaiva, Vaishnava, and Shakti works can be seen at the temple’s basement level; one particularly noteworthy set of carvings is a series depicting the twelve incidents from Krishna’s boyhood, which is significant to Vaishnavism.

The building is a multi-level, freestanding temple complex that is twice as large as the Parthenon in Athens. To dig the temple, the artists are said to have excavated three million cubic feet of stone, or around 200,000 tons.

Although the Rashtrakuta monarch Krishna I (r. 756–773 CE) is credited with building the temple, Pallava architectural features have also been observed. The courtyard’s measurements are 30 meters high by 46 meters wide at the base (280 by 160 by 106 feet). There is a little gopuram at the entrance.

A Dravidian shikhara and a flat-roofed mandapa supported by sixteen pillars are elements of the central shrine that houses the lingam. On a veranda in front of the temple is a picture of Shiva riding Nandi, the sacred bull. The main temple has two walls with rows of sculptures on the north and south sides that represent the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, respectively.

Cave 15: Dashavatara

Sometime after Cave 14 (Ravan ki Khai, Hindu), another important excavation was finished, the Dashavatara temple, also known as Cave 15. The cells and arrangement of Cave 15 resemble those of Buddhist Caves 11 and 12, suggesting that this cave was originally meant to be a Buddhist cave.

Nevertheless, the inclusion of non-Buddhist elements, such as a Nrtya Mandapa (a pavilion for Indian classical dance) near the entrance, implies that this was not the case. James Harle reports that several Hindu deities have been included into the Buddhist caves in the area and that Hindu pictures have been discovered in Buddhist Cave 11.

The contrasting designs of the Buddhist and Hindu caves may have been inspired by one another, or possibly a Buddhist cave that was originally intended was transformed into a Hindu monument.

As per Geri Malandra’s assertion, the Buddhist caves at Ellora were not an addition to the pre-existing Brahmanical Tirtha (a Hindu pilgrimage destination); rather, they were an incursion.

Furthermore, the original purpose and character of these cave temples are speculative, given that both the Hindu and Buddhist caves were primarily nameless and that no donor inscriptions other than those of the Hindu kingdoms that erected the Buddhist Ellora caves have been found.

The Hindu temple located in Cave 15 is composed of an open court with an excavated two-story temple at the back and a free-standing massive mandapa in the middle. On the upper level, large sculpture panels that depict a variety of subjects, including the 10 avatars of Vishnu, are situated between the wall columns.

A Dantidurga inscription, located on the rear wall of the front mandapa, is essential to determining the temple’s antiquity. The cave’s most exquisite relief, according to Coomaraswamy, is the death of Hiranyakashipu, with Vishnu appearing as a man-lion (Narasimha) and placing a deadly hand on his shoulder. It is a sculpture from the Rastrakoot dynasty.

The Gangadhara, the union of Shiva and Parvati, the Tripurantika of the Shakti tradition, Markendeya, Garuda, facets of life, Nandi in mandapa, dancing Shiva, Andhakasura, Govardhanadhari, Gajendravarada, and other artwork are among the other reliefs found in Cave 15.

According to Carmel Berkson, the panels are organized in dyads that support one another by exhibiting “cooperative but also antagonistic energy” and a mutuality of power transmission.

Additional Hindu caves

Other noteworthy Hindu caves include Nilkantha (Cave 22) and Ravan ki Khai (Cave 14), both of which have a large collection of sculptures. Cave 25 has a ceiling carving of Surya in particular.

The Monuments of Buddhism: Caves 1–12

These caverns lie on the southern side, and their construction dates range from 600–730 CE, or from 630–700 CE. Although caves 1–5 were built in the first phase (400–600) and caves 6–12 in the later phase (650–750) of the Buddhist cave construction, it was once believed that the Buddhist caves were the oldest buildings, dating from the fifth to the eighth century.

However, contemporary scholars now believe that Hindu cave construction predates the Buddhist cave construction. The oldest Buddhist cave is Cave 6, followed by Caves 5, 2, 3, 5 (right wing), 4, 7, 8, 10, and 9. The final two caves are Caves 11 and 12, sometimes referred to as Do Thal and Tin Thal, respectively.

Viharas, or monasteries with prayer halls, make up eleven of the twelve Buddhist caves. These are huge, multi-story structures cut into the mountainside that contain living and sleeping quarters, kitchens, and other rooms.

There are shrines in the monastery caves with sculptures of saints, bodhisattvas, and Gautama Buddha. Some of these caverns have been sculpted to attempt to replicate the appearance of wood.

Buddhist caves number five, ten, eleven, and twelve are significant architecturally. Among the Ellora caves, Cave 5 is special since it was constructed like a hall with a Buddha statue in the back and two parallel refectory benches in the center.

There are just two Buddhist caves in India that are set up like this, and that is Cave 11 of the Kanheri Caves. While Cave 10, also known as the Vīśvakarmā Cave, is a significant Buddhist prayer hall, Caves 1 through 9 are all monasteries.

The three-story Mahayana monastery caverns located in caverns 11 and 12 are home to a multitude of goddesses, statues, and Bodhisattva-related imagery. They are associated with Vajrayana Buddhism. These provide strong proof that by the eighth century CE, Buddhism’s Vajrayana and Tantra concepts were well-established throughout South Asia.

The Cave of Vishvakarma

Among the Buddhist caves, Cave 10 is noteworthy. Constructed about 650 CE, it is a chaitya prayer hall known as the “Vishvakarma cave.” Due to a finish applied to the rock that makes it resemble wooden beams, it is also known as the “Carpenter’s Cave”. The multi-story entrance leads to a stupa hall resembling a cathedral, called chaitya-griha (prayer house). A fifteen-foot statue of Buddha sitting in a preaching position sits at the center of this cave.

In Cave 10, a chapel-like prayer hall with eight secondary cells—four on the right and four on the rear wall—as well as a portico in front are combined with a vihara. Built along the lines of Ajanta Caves 19 and 26, it is the sole devoted chaitya griha among the Buddhist caves.

In addition, Cave 10 has a side link to Ellora’s Cave 9 and an arched window known as a gavaksha, or chandrashala.

The Visvakarma cave’s main hall has an apsidal layout and is supported by 28 octagonal columns with simple bracket capitals that divide it into a central nave and side aisles. The stupa at the apsidal end of the Chaitya Hall is adorned with a massive image of the Buddha sitting in the teaching position (vyakhyana mudra).

At his back is engraved a big Bodhi tree. The hall features a vaulted ceiling with ribs (called triforium) cut into the rock to resemble wooden ones. The large relief artwork features figures like as performers, dancers, and singers, while the friezes above the pillars depict Naga queens.

A set of steps leads up to a court carved out of rock at the front of the prayer hall. Apsaras and monks in meditation are among the many Indian images adorning the carved facade of the Cave’s entrance. There are pillared porticos with little apartments set into their rear walls on either side of the top level.

The chaitya’s pillared verandah features a solitary cell in the far end of the rear wall and a modest shrine at either end. The caps of the corridor columns are ghata-pallava (vase and foliage) with enormous squared shafts.

The many levels of Cave 10 also have idols of both male and female deities carved in the eastern Indian style of the Pala dynasty, including Maitreya, Tara, Avalokitesvara (Vajradhamma), Manjusri, Bhrkuti, and Mahamayuri. Various artwork in this cave also show influences from southern India.

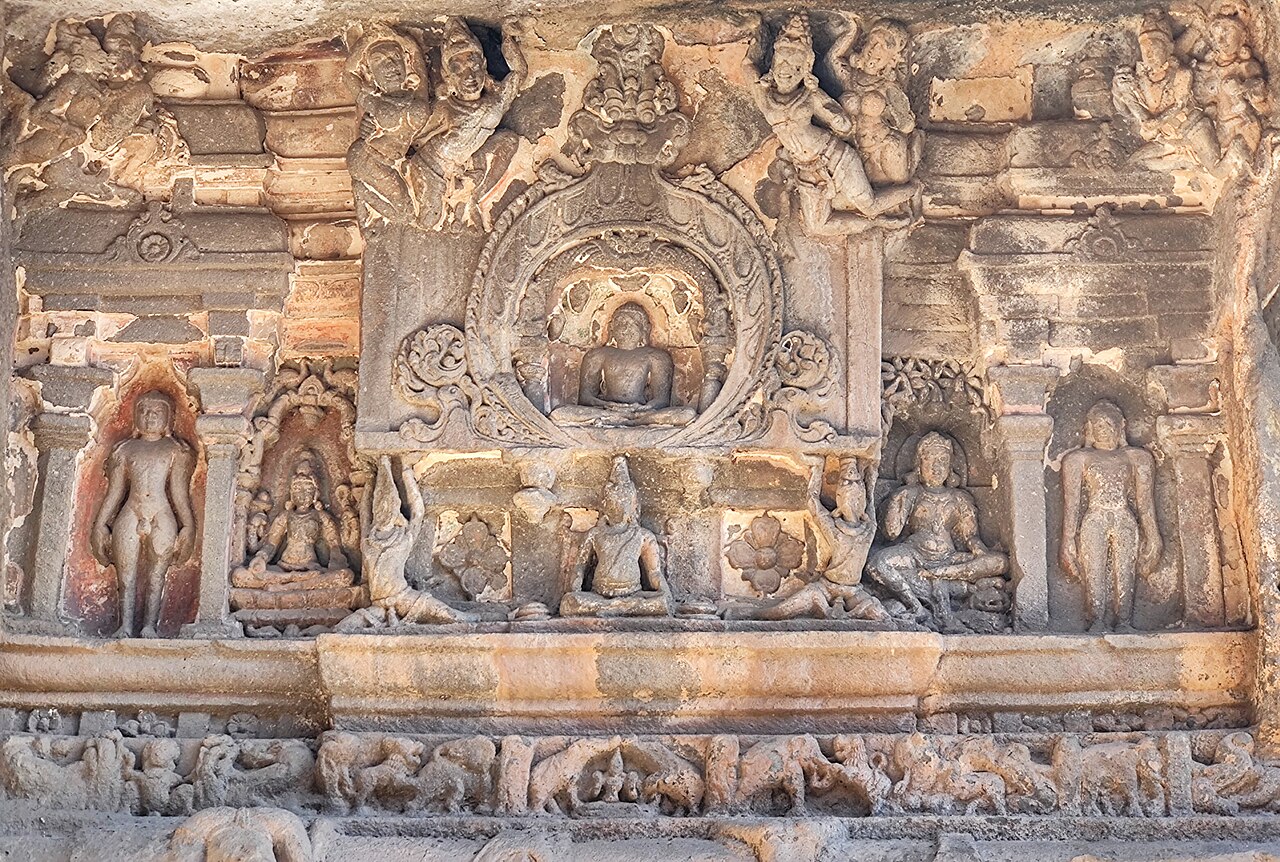

The Monuments of Jainism: Caves 30–34

The five Jain caves of the Digambara sect, which were dug in the ninth and early tenth century, are located at the northern end of Ellora. Despite being smaller than the Buddhist and Hindu caves, these caves have extremely intricate decorations. They were constructed about the same period as the Hindu caves of later times, and they both include comparable architectural and religious concepts including a pillared veranda, symmetric mandapa, and puja (worship).

In contrast to Hindu temples, though, the representation of the twenty-four Jinas—spiritual warriors who have achieved freedom from the never-ending cycle of reincarnations—is given special attention.

Jose Pereira claims that the five caverns were really 23 separate excavations conducted across various time periods. Thirteen are in the Indra Sabha, six in the Jagannatha Sabha, and the remaining ones in the Chhota Kailash.

Pareira studied a variety of sources to come to the conclusion that the Jain caves at Ellora most likely started in the late eighth century, and that work on them continued into the twelfth and thirteenth centuries until the Delhi Sultanate’s conquest of the area put a stop to them. Votive inscriptions from 1235 CE attest to this; the giver claims to have “converted Charanadri into a holy tirtha” for Jains with the donation of the excavation of lordly Jinas.

The Chhota Kailash (cave 30, 4 excavations), the Indra Sabha (cave 32, 13 excavations), and the Jagannath Sabha (cave 33, 4 excavations) are particularly significant Jain sanctuaries. Cave 31 is an incomplete four-pillared hall and shrine. There is an opening on the left side of Cave 33 that leads to the little cave known as Cave 34.

Among the devotional sculptures in the Jain caves are some of the oldest Samavasarana representations. Because it is the hall where the Tirthankara preaches after achieving Kevala Jnana (liberating omniscience), the Samavasarana is very significant to the Jains.

The coupling of revered Jain characters, Parsvanatha and Bahubali, who occur 19 times together, is another intriguing aspect of these caves. The goddesses Sarasvati, Sri, Saudharmendra, Sarvanubhuti, Gomukha, Ambika, Cakresvari, Padmavati, Ksetrapala, and Hanuman are depicted in other noteworthy artworks.

Chhota Kailasha: Cave 30

Because the sculptures on the Chhota Kailasha resemble those in the Kailasha temple, it is also known as the small Kailasha. This temple was probably constructed in the early ninth century, a few decades after the Kailasha Temple was finished, and at the same time as the lower level of the Indra Sabha.

It has two life-size reliefs of dancing Indra, one with eight arms and the other with twelve, both covered in jewels and wearing a crown. The different mudras on Indra’s arms are evocative of the dancing Shiva paintings that can be seen in the surrounding Hindu caves. But there are a few peculiarities in the iconography that suggest this cave depicts a dancing Indra rather than a dancing Shiva.

Given that the Jain religion emphasizes contemplative abstinence, art historian Lisa Owen has questioned whether music and dancing were a component of 9th-century Jainism. For instance, Rajan has suggested that Cave 30 May was formerly a Hindu structure that was subsequently transformed into a Jain temple. Owen, nevertheless, contends that a deeper understanding of the joyous artwork in this temple would be found in Jainism’s Samavasarana theory.

Given that Book Three of the Hindu Mahabharata portrays Indra’s dwelling as one populated with a variety of heroes, courtesans, and artists, amid a setting akin to heaven, the overlap between Jain and Hindu myths has generated misunderstanding. Similar to the Hindu caves, this picture is used repeatedly in Cave 30 to establish the temple’s location.

The symbolism at the temple’s center, where Jinas—the locations where Jain devotees would carry out their ritualistic abhisheka (worship)—and meditating figures are more common, however, are more in line with the central concepts of Jainism.

Cave No. 31

Cave 31, which had several engravings, a tiny shrine, and four pillars, was unfinished. The left and right walls of the hall are adorned with carvings of Parshvanatha, who is watched over by Yaksha Dharanendra, who is adorned with seven hoods, and Gommateshvara. The idol of Vardhamana Mahavir Swami is housed within the shrine. On a lion’s throne, the idol is sitting in the padmasan posture, with a chakra visible in the throne’s center panel. On the left side of the shrine is the image of Yaksha Matanga riding an elephant, and on the right side is a picture of Yakshi Siddhaiki sitting in savya-lalitasana on a lion, holding a baby on her lap.

Cave 32: Indra Sabha

Excavated in the 9th century, Cave 32 is the two-story Indra Sabha, with a monolithic shrine in its court. The temple was given the incorrect name “Indra Sabha” because 19th-century historians mistook the Jain Yaksas for several representations of Indra that could be seen in Buddhist and Hindu artwork.

Indra is a prominent figure in all three of the major world religions, but in Jainism, he is especially significant because, according to the Adipurana, a sacred text of the Jain faith, he is not only one of the 64 gods who rule over the heavens, but also the king of Saudharmakalpa, the first Jain heaven, and the chief architect of the celestial assembly hall.

The Indra Sabha Jain temple is important historically because it has literary documents and layered deposits that show the Jain community worshiped there actively. Rituals were specifically said to have taken place on the upper level, maybe with a major role for the artwork.

The temple is decorated with several sculptures, including one of a lotus blossom on the roof, just like many other caves in Ellora. A figure of Ambika, the yakshini of Neminath, sitting on her lion beneath a mango tree and bearing fruit, is located on the upper level of the shrine, which was dug near the back of the court.

Sarvatobhadra is the focal point of the shrine. Here, four Jain Tirthankaras—Rshibha (the first), Neminatha (the 22nd), Parsvanatha (the 23rd), and Mahavira (the 24th)—are arranged in accordance with the cardinal directions to create a place of prayer for followers.

Cave 33 of the Jagannatha Sabha

Based on the inscriptions on the pillars, the second-largest Jain cave at Ellora is called Jagannatha Sabha (Cave 33), and it is believed to have been built in the ninth century. It’s a two-story cave carved from a single rock with twelve enormous pillars and elephant heads protruding towards a porch.

The hall is composed of four pillars in the center, two large square pillars facing forward, and an interior square major hall supported by pillars with fluted shafts. The pillars are all well-carved with brackets, ridges, and caps. Parshvanatha and Mahavira, the final two Jain Tirthankaras, are shown inside the main idols.

Cave No. 34

Although some of the writings in Cave 34—referred to as J26 by historian José Pereira—have not yet been interpreted, they were most likely written between 800 and 850 CE. It is believed that certain inscriptions, like the one authored by Sri Nagavarma, belong to the 9th or 10th century.

This cave has a giant sitting Parshvanatha Jina accompanied by four servants from the camera, two of whom appear to come from behind the Jina’s throne with fly-whisks. This cave near the Jina also has a massive pair of yaksa-yaksi, like with many other Jain excavations. A bearded person stands behind the cave, holding a bowl filled with circular sacrificial offerings that resemble sweet meat or pindas (rice balls).

This implies that the scenario could be connected to a shraddha ritual or some kind of Jain religious worship. The Parshvanatha in the cave is joined by other sculptures depicting musicians playing a range of instruments, including horns, drums, conchs, trumpets, and cymbals. It is paired with a standing Gommateshvara.

One of the cave’s most remarkable features is the enormous, open lotus sculpture on its rooftop and ceiling, which is unique to Ellora and can only be found in one Hindu Cave 25 and one other Jain excavation. The lotus, positioned on the cave instead of a sculpture, indicates that the temple is a hallowed location.

Lord Parshvanath’s picture etched into a rock

A Jain shrine on a hill northeast of the main cave complex has a 16-foot (4.9-meter) Rashtrakuta-era rock-carved deity of Lord Parshvanath bearing an inscription dating to 1234 A.D. Padmavati and Dharaıendra surround the immaculate picture.

The location is identified as Charana Hill, a sacred spot, in the inscription. Since it is still used for religion, the ASI does not provide protection. It is reached after climbing six hundred steps. The village’s Jain Gurukul is in charge of it.

Visitors, damage, and degradation

Several accounts from the decades after the caves’ construction show that they were often visited, especially as Ellora was visible from a trade route. For instance, Buddhist monks are known to have visited Ellora frequently in the ninth and tenth centuries. The site of a huge temple, a center of Indian pilgrimage, and one with thousands of cells where devotees live is wrongly referred to as “Aladra” by the 10th-century Baghdad resident Al-Mas‘udi.

Ala-ud-Din Bahman Shah’s chronicles from 1352 CE describe his camping at the site. Firishta, Thevenot (1633–67), Niccolao Manucci (1653–1708), Charles Warre Malet (1794), and Seely (1824) penned further documents.

Although Ellora is important, some accounts give false information about how it was built. Niccolao Manucci, a Venetian traveler whose account of Mughal history was well received in France, wrote in his description of the caves that the Ellora caves “…were executed by the ancient Chinese” based on his assessment of the workmanship and what he had been told. During the Mughal era, Ellora was a well-known location.

Numerous Mughal aristocrats, including Emperor Aurangzeb, had family picnics there. According to Aurangzeb’s courtier Mustaid Khan, people came to the region year-round, but especially during the monsoon.

In addition, he mentioned that all of the walls and ceilings had “many kinds of images with lifelike forms” carved on them, but the monuments themselves were in a state of “desolation in spite of its strong foundations.”

The earliest evidence that Ellora was no longer being used in the 13th century comes from the Lilacharitra, a Marathi work written in the late 13th century CE. Islamic court records stated that at this time, the Yadava dynasty’s capital, Deogiri, which was located around 10 kilometers from Ellora, was subjected to frequent attacks.

As a result, in 1294 CE, it succumbed to the Delhi Sultanate. José Pereira claims that there is proof that construction in the Ellora Jain caves had prospered under Singhana, the Yadava dynasty ruler from around 1200 to 1247 CE. Jain worshipers and visitors continued to use these tunnels until the 13th century. But when the area was ruled by Islam in the late 13th century, Jain religious activities stopped.

While there is significant damage to the idols in the Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain monuments at Ellora, the elaborate carvings of natural elements on the walls and pillars are still intact. The destruction of idols and pictures dates back to the 15th and 16th centuries when Muslim forces carried out iconoclasm in this Deccan peninsula area.

Muslims, according to Geri Malandra, were so offended by “the graphic, anthropomorphic imagery of Hindu and Buddhist shrines” that they did this destruction.

Some Muslims of this era are known to have expressed concern regarding the wanton damage and “deplored it as a violation of beauty,” according to Carl Ernst. Muslim historians of the Islamic Sultanate period mention Ellora in their descriptions of the widespread damage and fanatical destruction of idols and artwork of the region.

Inscriptions of Ellora

The most well-known of the several sixth-century inscriptions at Ellora is an inscription by Rashtrakuta Dantidurga (c. 753–757 CE) on the rear wall of Cave 15’s front mandapa, which claims that he prayed there.

Three inscriptions in Jain Cave 33, Jagannatha Sabha, list donors, and monks’ names. An inscription at the Parshvanath temple atop the hill dates from 1247 CE and lists a donor’s name from Vardhanapura.

The successor and uncle of Dantidurga, Krishna I (c. 757–783 CE), is credited with building the Great Kailasa temple (Cave 16). According to an inscription on a copper plate discovered in Baroda, Gujarat, Krishnaraja constructed a magnificent structure on a hill near Elapura (Ellora):

was responsible for the construction of a magnificent temple on the hill at Elapura. Upon witnessing its splendor, the most accomplished immortals in heavenly vehicles exclaimed, “This Shiva temple is self-existent; in a thing made by art such beauty is not seen (…).” The building’s architect, who went by the name (…), was startled and said, “Oh, how was it that I built it!”

— Karkaraja II copper inscription, 812 CE

Latest Updates

Let’s imagine, explore, and uncover the mysteries together!

Let’s imagine, explore, and uncover the mysteries together!