The thirty rock-cut Buddhist cave structures known as the Ajanta Caves are located in the Aurangabad area (also known as the Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar district) in the Indian state of Maharashtra. They date from the second century BCE to around 480 CE. One of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites is the Ajanta Caves. The caves, which are widely recognized as masterpieces of Buddhist religious art, contain sculptures and paintings that have been called among the best examples of ancient Indian art that have survived. These include expressive paintings that convey emotions via gesture, position, and shape.

The caverns were constructed in two stages: the first began in the second century BCE, while the second, according to earlier reports, took place between 400 and 650 CE. Later research places the second phase of construction between 460 and 480 CE.

The Ajanta Caves are a series of ancient Buddhist temples, or Chaityas, and monasteries, or Viharas, carved out of a 75-meter (246-foot) rock wall. Along with rock-cut sculptures of Buddhist deities, the caverns also have paintings that show the Buddha’s former incarnations and rebirths and visual narratives from Aryasura’s Jatakamala.

According to written accounts, these caverns provided monks with a monsoon refuge and a place to rest for pilgrims and traders in ancient India. Historical documents testify to the abundance of vibrant colors and mural wall paintings throughout Indian history, but the biggest collection of surviving ancient Indian wall paintings is found in the Caves 1, 2, 16, and 17 of Ajanta.

Various memoirs written by Chinese Buddhist travelers during the medieval times mention the Ajanta Caves. They were hidden by the forest until Captain John Smith, a British colonial commander, “discovered” them by mistake while on a tiger-hunting expedition in 1819 and brought them to the notice of the West. The caverns are located on the steep northern wall of the Deccan plateau’s U-shaped River Waghur valley. There are several waterfalls in the gorge that may be heard when the river is high from outside the caves.

Transport

Ajanta is one of Maharashtra’s most popular tourist destinations because of the Ellora Caves. It is around 350 kilometers (220 miles) east-northeast of Mumbai, 59 kilometers (37 miles) from the Indian city of Jalgaon, and 104 kilometers (65 miles) from the city of Aurangabad. The Ellora Caves, which have Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu caves—the latter of which dates to a time similar to Ajanta—are located 100 kilometers (62 miles) from Ajanta.

The Ellora Caves, as well as other locations including the Elephanta Caves, Aurangabad Caves, Shivleni Caves, and the cave temples of Karnataka, are additional examples of Ajanta architecture. Mumbai is the closest airport, followed by Jalgaon and Sambhaji Nagar. The closest train stations are Bhusawal and Jalgaon.

Past Events

Most people assume that the Ajanta Caves were created in two separate stages: the first phase occurred during the first and second centuries CE and the second phase occurred several centuries later.

There are 36 distinguishable foundations in the caverns, some of which were unearthed after the caves were first numbered 1 through 29. The letters of the alphabet have been added to the later-discovered caves. For example, cave 15A has been identified between caves 15 and 16. Convenience dictated the cave numbering system, which does not correspond to the sequence in which they were built.

First-period caves (satavahana)

Caves 9, 10, 12, 13, and 15 A make up the oldest group. These caverns include paintings that tell tales from the Jatakas. The Gupta period’s artistic impact may be seen in later caves, however opinions on when century the early caverns were constructed vary. Walter Spink states that they were created between 100 BCE and 100 CE, most likely with the support of the local Hindu Satavahana dynasty (230 BCE–220 CE). Some date systems favor the Mauryan Empire era, which lasted from 300 to 100 BCE.

Of these, caves 9, 10, and 12 are stupa with chaitya-griha-shaped prayer halls, while caves 13 and 15A are vihāras (descriptions of these types may be found in the architectural section below). The stupa was emphasized in the early Satavahana era caves rather than figurative sculpture.

Spink claims that after the creation of the Satavahana period caverns, the site was not used again until the middle of the fifth century. But according to the records provided by the Chinese pilgrim Faxian around 400 CE, the early caves were used throughout this inactive era, and Buddhist pilgrims paid a visit to the location.

Caves from the Vakataka or Later Era

At the Ajanta Caves location, the second phase of development got underway in the fifth century. Long believed to have been constructed over an extended period from the fourth to the seventh century CE, the later caves were actually mostly constructed between 460 and 480 CE, during the reign of the Hindu Emperor Harishena of the Vākāṭaka dynasty, according to a series of studies conducted in recent decades by Walter M. Spink, the foremost authority on the caves.

Although some academics have criticized this viewpoint, most writers of general books on Indian art, including Huntington and Harle, today generally agree with it.

The theistic Mahāyāna, or Greater Vehicle tradition of Buddhism, is credited with the second phase. The 1–8, 11–14–29 caves belong to the second phase; some of them may be expansions of previous caves.

The remaining caves are viharas, while caves 19, 26, and 29 are chaitya-grihas. During this time, the most ornate caverns were created, and some of the earlier caves were also renovated and painted.

According to Spink, dates for this era may be determined with a very high degree of accuracy; a more detailed explanation of his chronology is provided below. Though there is still controversy, Spink’s ideas—at least the general conclusions—are becoming more and more accepted.

The conventional dating of “the second phase of paintings started around 5th–6th centuries A.D. and continued for the next two centuries” is still displayed on the Archaeological Survey of India website.

A few years after Harishena’s death in 480 CE, according to Spink, affluent benefactors abandoned the completed Ajanta Caves’ development. However, according to Spink, the wear on the pivot holes in the caverns built about 480 CE suggests that the caves have been inhabited for a while. The second stage of Ajanta’s building and ornamentation reflects the pinnacle of Classical India, often known as India’s golden period.

The Vakatakas were, in fact, one of the most powerful empires in India at the time because the Gupta Empire was already waning due to internal political strife and Hūṇa attacks.

At the time the Ajanta caves were constructed, a portion of the Hūṇas, the Alchon Huns of Toramana, were precisely governing the neighboring region of Malwa, at the doorstep of the Western Deccan.

At the time when some designs of Gandharan inspiration, like Buddhas in robes with lots of folds, were being decorated in the Ajanta or Pitalkhora caves, the Huns may have served as a cultural bridge between the region of Gandhara and the Western Deccan thanks to their control over vast areas of northwest India.

Richard Cohen claims that fragmentary medieval graffiti and a description of the caverns by the Chinese traveler Xuanzang from the 7th century indicate that the Ajanta caverns were recognized and perhaps used later on, but there was no consistent or permanent Buddhist community present. The Ajanta caves are described as twenty-four rock-cut cave temples with magnificent idols apiece in Abu al-Fazl’s 17th-century work Ain-i-Akbari.

Colonial period/Revolution

While out hunting tigers on April 28, 1819, a shepherd child from the area led a British commander named John Smith of the 28th Cavalry to the entrance to Cave No. 10. Locals already knew a lot about the caverns.

In order to remove the tangled jungle vegetation that was making it impossible to access the cave, Captain Smith went to a nearby town and invited the residents to gather to the location armed with axes, spears, torches, and drums. He initially saw ceilings with exquisitely rendered faces, and upon seeing monastery halls, he was able to determine that the ceilings were Buddhist in nature.

Then, he purposefully ruined a picture on the wall by erasing his name and the current date over the bodhisattva artwork. He was standing on a five-foot-tall mound of debris accumulated over time, so the inscription was well above the normal adult’s eye level. In 1822, William Erskine presented a presentation on the caverns to the Bombay Literary Society.

The caverns rose to fame in a few of decades due to its remarkable and distinctive murals, stunning architecture, and unusual surroundings. In the century after their finding, many sizable endeavors were undertaken to replicate the paintings.

Under the direction of John Wilson, the Royal Asiatic Society formed the “Bombay Cave Temple Commission” in 1848 with the goal of organizing, cataloging, and clearing the most significant rock-cut sites in the Bombay Presidency. This served as the foundation for the newly formed Archaeological Survey of India in 1861.

The Ajanta site was located in the princely state of Hyderabad during the colonial era, not in British India. The last Nizam of Hyderabad, Mir Osman Ali Khan, hired specialists to repair the artwork, turned the location into a museum, and constructed a road so that visitors could visit the site for a charge in the early 1920s.

According to Richard Cohen, these initiatives led to early mismanagement and accelerated the site’s decline. The Maharashtra state government constructed facilities for arrival, and transportation, and improved site management after independence. Good parking and public restrooms can be found at the Contemporary Visitor Center. Buses run by ASI operate on a regular schedule between the Visitor Center and the caverns.

To repair the murals in the caverns, the Director of Archaeology at the Nizam sent in two Italian experts: Count Orsini and Professor Lorenzo Cecconi. Regarding Cecconi and Orsini’s study, the last Nizam of Hyderabad’s Director of Archaeology stated:

Due to the strong ideas and scientific approach used in the restorations of the caverns and the cleaning and protection of the frescoes, these unparalleled monuments will have a new lease of life for at least a few decades.

Even with these attempts, the paintings’ quality eventually declined once more due to neglect.

The Ajanta caves have been recognized as one of India’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 1983. The Ajanta and Ellora Caves are now the most visited tourist destinations in Maharashtra.

Because of their popularity, the caves—especially the paintings—are more vulnerable to damage during the busy vacation season. In order to alleviate crowding in the original caves and provide visitors with a clearer visual representation of the paintings—which are poorly lit and difficult to read in the caves—the Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation announced plans in 2012 to expand the ASI visitor center at the entrance with full replicas of caves 1, 2, 16 & 17.

Locations and Monasteries

Places

The caves are part of the Deccan Traps, a series of cliffs sculpted by volcanic eruptions at the end of the Cretaceous geological era, out of granite and flood basalt rock. The horizontally stratified rock has varying degrees of quality. The artists had to modify their carving techniques and designs in certain areas due to the variations found in the rock strata. In the centuries that followed, the inhomogeneity of the rock also caused fractures and collapses, as shown by the disappearance of the portico to Cave 1.

As can be seen from several of the incomplete caves, including the partially constructed vihara caves 21 through 24 and the abandoned incomplete cave 28, excavation started by digging a small tunnel at roof level and then expanded downward and outward.

The complex carvings on the pillars, ceiling, and idols were probably created by the sculpting artists in addition to mining the rocks; also, the painting and sculpture inside a cave were done in tandem. At the highest point of the horseshoe-shaped valley, between caves 15 and 16, as viewed from the river, a magnificent entrance to the site was carved.

It is adorned with elephants on both sides and a nāga, or guardian Naga (snake) god. Some cave temples in India, including those associated with Jainism and Hinduism, use comparable techniques and artistic skills. The Ellora, Ghototkacha, Elephanta, Bagh, Badami, Aurangabad, and Shivleni caves are a few of them.

It appears that the first-period caves were funded in part by many donors in order to accrue merit, as multiple inscriptions document the giving of specific sections of a single cave. According to inscriptions like those found in Cave 17, the later caves were all ordered as a unified unit by a single sponsor who belonged to the local monarchs or their court elites.

This was likely done because the caverns were thought to have worth in Buddhist afterlife beliefs. Following Harisena’s passing, smaller donors who were driven by merit added miniature “shrinelets” or statues to already-existing caves. Approximately two hundred of these “intrusive” additions were made of sculpture, and there were even up to three hundred intrusive paintings in Cave 10 alone.

Monasteries

Vihara halls with symmetrical square floor designs make up the majority of the caverns. Smaller square dorm chambers set into the walls are linked to each vihara hall. A shrine or sanctuary is attached to the back of the cave, centered on a large statue of the Buddha, along with incredibly detailed reliefs and deities nearby, as well as on the pillars and walls, all carved out of the natural rock.

The majority of the caves were carved during the second period. The transition from Hinayana to Mahāyāna Buddhism is reflected in this alteration. It’s common to refer to these caverns as monasteries.

Square columns that delineate the center square space of the viharas’ interiors provide an almost square open area. On either side of these are long, rectangular aisles that resemble cloisters. Numerous tiny cells with tiny recesses on their back walls and roughly square shapes may be seen along the side and rear walls.

These chambers are accessible through a short entryway. Their doors were made of wood at first. There is a bigger shrine room with a massive Buddha statue in the center of the back wall.

The early viharas are devoid of shrines and are considerably simpler. According to Spink, the transition to a shrine-adorned design occurred in the midst of the second period. Numerous caves were modified to incorporate a shrine either during or after the initial phase of excavation.

Though it is fairly typical of the later group, the layout of Cave 1 displays one of the biggest viharas. Numerous others, like Cave 16, don’t have the shrine’s entryway, which goes directly off the main hall. With sanctuaries on both levels, Cave 6 consists of two viharas, one above the other, joined by interior stairs.

Halls of worship

The other kind of main hall architecture is called chaitya-griha, which means “the house of stupa” and has a smaller rectangular shape with a high arched roof. A symmetrical row of pillars divides this hall lengthwise into a nave and two smaller side aisles, with a stupa situated in the apse. There are pillars all around the stupa, and there is a circular path that one may stroll around.

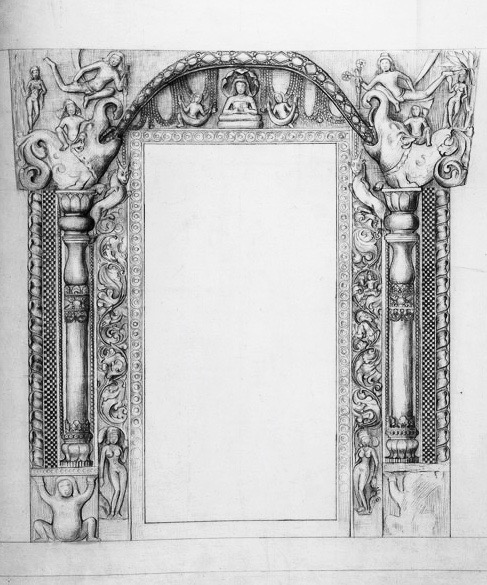

A few of the caverns include ornately carved entrances, while others feature sizable windows that let light in. A colonnaded porch or verandah is frequently present, and the cave’s breadth is extended by an additional area within the entrances.

The earliest worship halls at Ajanta date from the second to the first century BCE, while the most recent ones date from the late fifth century CE. Both buildings’ construction is similar to that of a Christian church, although without the chapel chevette or crossing.

The Lomas Rishi Cave of the Ajivikas near Gaya in Bihar, which dates to the third century BCE, is one of the earlier rock-cut cave sculptures of ancient India that has the Cathedral-style architecture seen in the Ajanta Caves. Worship or prayer halls are the names given to these chaitya-griha.

Caves 9 and 10 from the early era and Caves 19 and 26 from the later period are the four finished chaitya halls. All have high ceilings and a central “nave” that leads to the stupa, which is located in the rear but enables people to walk behind it. This is characteristic of other stupas, as walking around stupas was and still is a common part of Buddhist devotion (pradakshina).

The earliest two are believed to have employed real wooden ribs and are now smooth, with the original wood likely having perished. The latter two, on the other hand, have high ribbed roofs cut into the rock that mimic timber forms.

A massive relief sculpture of the Buddha, standing in Cave 19 and seated in Cave 26, fronts the stupa in the two later rooms, which have an odd configuration also seen in Cave 10 at Ellora. A very late and unfinished chaitya hall is Cave 29.

The earliest period’s artwork has extremely basic, unadorned columns in both of the chaitya halls. These columns were eventually painted with pictures of the Buddha, humans, and robed monks. Columns from the second era were much more creative and diverse; they frequently had elaborately carved capitals that spread widely and changed profile as they rose in height.

Numerous columns, some fluted and others carved with designs all over, like in cave 1, with floral themes and Mahayana deities carved all over them.

Paintings

Almost all of the mural paintings and the majority of the Ajanta caves were created during a second building period, some 600 years after the first. The Jataka stories are mostly depicted in the paintings found in the Ajanta caves. These are stories from Buddhism that recount the Buddha’s past incarnations. The fables and legends contained in Hindu and Jain scriptures also include old principles and cultural heritage that are ingrained in these tales.

The Buddha’s life example and the sacrifices he made in hundreds of previous incarnations—in which he is said to have taken on the form of an animal or a human—serve as examples for the Jataka stories.

There are still mural paintings that can be seen in both the older and later cave groupings. The earlier caves (Caves 10 and 11) contain several mural fragments that are essentially the only examples of ancient Indian paintings from this era that have survived.

These fragments “show that Indian painters had mastered an easy and fluent naturalistic style by Sātavāhana times, if not earlier, dealing with large groups of people in a manner comparable to the reliefs of the Sāñcī toraņa crossbars.” There is evidence of a similar artistic style and some linkages to the art of Gandhara.

Large, comparatively well-preserved mural paintings in four of the later caves capture “the great glories not only of Gupta but of all Indian art” and, according to James Harle, “have come to represent Indian mural painting to the non-specialist”. They may be divided into two style groups: the most well-known ones are found in Caves 16 and 17, whereas Caves 1 and 2 appear to have later paintings.

Although it was believed that the latter set was a century or later than the others, Spink’s updated chronology would put them in the 5th century as well, maybe contemporaneous with it in a more advanced style or one that represented a team from a different location.

Paintings in “dry fresco” are done over a surface covered in dry plaster as opposed to wet plaster. Every artwork seems to have been created by artists who were financed by sophisticated metropolitan clientele and discerning connoisseurship. Literary sources have informed us that painting was a popular art form throughout the Gupta dynasty.

In contrast to many Indian mural paintings, these compositions depict expansive scenes that branch out from a central person or group rather than being arranged in horizontal bars like a frieze. Additionally, the ceilings are painted with intricate and complex ornamental designs, many of which are inspired by art.

The paintings in cave 1, which Spink claims were ordered by Harisena himself, focus on the Jataka stories that depict the Buddha in past incarnations as a monarch rather than as a deer, elephant, or another Jataka animal. The Buddha is shown in the scenes preparing to give up the life of royalty.

As demonstrated by caves 2 and 16 in particular, the later caves often appear to have been painted on completed sections while excavation work proceeded elsewhere in the cave. Based on Spink’s chronology of the caves, the absence of painting in areas like cave 4 and the shrine of cave 17, which were subsequently plastered in preparation for murals that were never completed, might be attributed to the cessation of work in 478 following a brief period of activity.

Spink’s timeline and the history of caves

In contrast to previous academics, Walter Spink has produced a fairly accurate and circumstantial chronology for the second era of construction on the site, placing it totally in the 5th century over the course of the last few decades.

This is supported by data from the numerous incomplete cave features, the age of neighboring cave temple sites, artistic style and inscriptions, and a comparative chronology of the dynasties. Like other researchers, he dates the first set of caves only roughly to “between 100 BCE – 100 CE,” but he believes that at some time in the past, they were fully abandoned and stayed that way “for over three centuries.”

This was altered during the Vakataka Dynasty’s Hindu ruler Harishena, who ruled from 460 until his death in 477 and financed the construction of many additional caves. The Gupta Empire governed northern India during this time, and the Pallava dynasty ruled much of the south. Harisena’s authority expanded the Central Indian Vakataka Empire to cover a portion of the east coast of India.

Spink states that Harisena urged a group of cronies, such as his prime minister Varahadeva and Upendragupta, the sub-king whose domain included Ajanta, to excavate new caves. These caves were commissioned one at a time, and some of them had inscriptions attesting to their contribution.

This began about 462 in several caves at the same time. Threats from the nearby Asmaka rulers caused this work to be mostly halted in 468. After that, only Caves 1—a commission from Harisena—and 17–20—a commission from Upendragupta—were still under construction. The situation worsened to the point where, in 472, all work was ceased, a period Spink refers to as “the Hiatus”.

This lasted until around 475, by which time Upendragupta had been supplanted as the local monarch by the Asmakas.

After that, work was resumed, but was once again hampered by the death of Harisena in 477. Major excavation then stopped, with the exception of Cave 26, which the Asmakas were funding on their own. The Vakataka Dynasty came to an end when the Asmakas revolted against Harisena’s son.

Major excavations carried out between 478 and 480 CE by well-known benefactors were replaced by a plague of “intrusions”—statues put into already-existing caves and little shrines strewn wherever there was room between them.

These were commissioned by some of the less powerful people, the monks, who had not been able to add to the extensive excavations of the kings and courtiers before. They were added to the walls inside the caverns, the facades, and the return sides of the entrances.

“After 480, not a single image was ever made again at the site,” claims Spink. Nonetheless, there is an inscription by Rashtrakuta outside cave 26, which dates to the late seventh or early eighth century, indicating that the caverns were not abandoned until that time.

Spink states that “one should allow a margin of error of one year or perhaps even two in all cases” yet does not include the word “circa” in his dates.

Support from Buddhists and Hindus

The Buddha and the Hindu gods were both highly esteemed in Indian culture around the time the Ajanta Caves were constructed. The royal Vakataka benefactors of the Ajanta Caves most likely worshipped both Buddhist and Hindu deities, according to Spink and other academics. Inscriptions proving this point show that these rulers—also referred to as Hindu devotees—made Buddhist offerings to the caverns. As stated by Spink,

Varahadeva’s involvement in this matter might be explained by the possibility of worshiping both the Buddha and the Hindu gods, in the same way that the emperor Harisena could support the amazing Cave 1 despite the consensus among scholars that he was a Hindu, similar to previous Vakataka rulers.

Walter Spink, Ajanta: Development and History, Cave by Cave,

In addition, a recently unearthed burnt-brick vihara monastery opposite the caverns on the right side of the Waghora River revealed a ceramic plaque depicting Mahishasuramardini, popularly known as Durga.

This implies that the craftspeople may have been worshiping the deity. Yuko Yokoschi and Walter Spink assert that a large number of builders were employed by the Ajanta caves based on the discovery of 5th-century items nearby.

Cave No. 1

Located at the easternmost point of the horseshoe-shaped scarp, Cave 1 is the first cave that a tourist will come upon. Originally, this cave would have been near the end of the row in a less noticeable location. As per Spink’s account, this cave was among the final ones to be dug, as the prime locations had already been claimed. The Buddha figure in the center shrine was never fully dedicated for worship.

The lack of sooty deposits from butter lamps on the base of the shrine image and the absence of damage to the paintings—which would have resulted from any usage of the garland hooks surrounding the shrine—both attest to this. According to Spink, the Vākāṭaka Emperor Harishena was the work’s sponsor.

This is indicated by the cave’s concentration on royal iconography and the selection of Jataka stories that describe the Buddha’s former lives as royalty.

This cliff’s slope is steeper than that of the other caves, therefore in order to create a towering, imposing front, a significant incision had to be made into the slope, creating a spacious courtyard in front of the face. Before the current front, there was a columned portico that was “half-intact in the 1880s” according to photos taken at the location. However, this fell completely and the remnants, which still had beautiful carvings on them, were heedlessly tossed down the slope into the river and disappeared.

One of the most intricately carved facades, measuring 35.7 m by 27.6 m, features relief sculptures on entablature and ridges, with ornate carving adorning most surfaces. Along with other ornamental designs, there are episodes from the life of the Buddha engraved on them. The pictures from the 19th century show a two-pillared portico, which is no longer there.

The cave features a courtyard with vestibules supported by pillars on either side, fronting the cells. The plinth level is high on them. There are simple chambers at both ends of the porch in the cave. The porch may not have been dug during the most recent Ajanta period, when pillared vestibules were the norm, based on the lack of pillared vestibules on the ends.

There used to be paintings all over the porch; many of the remains are still visible, particularly on the ceiling. A center entryway and two side entrances make up the three doorways. To lighten the interiors, two square windows were cut between the doors.

The interior hall’s walls are 20 feet (6.1 m) in height and over 40 feet (12 m) in length. Inside, a square colonnade of twelve pillars supports the roof and forms roomy aisles along the sides.

An amazing sitting figure of the Buddha with his hands in the dharmachakrapravartana mudra is housed in a shrine carved into the back wall. There are four cells on the left, right, and back walls; however, the ends of the back aisle lack cells because of a rock fault.

Both the ceiling and the walls of Cave 1 are covered in artwork. Despite the fact that the entire project was never finished, they are in a decent amount of preservation. The scenes from the Jataka accounts of the Buddha’s previous incarnations as a bodhisattva, the life of Gautama Buddha, and those of his reverence are largely didactic, religious, and decorative.

The two over-life-size representations of the guardian bodhisattvas Padmapani and Vajrapani on either side of the Buddha shrine entrance on the wall of the back aisle are the two most well-known individual painted pictures at Ajanta (see illustrations above). The stories of Sibi, Sankhapala, Mahajanaka, Mahaummagga, and Champeyya Jataka are among the other notable paintings in Cave 1.

In addition, the cave paintings depict the narrative of Nanda, the story of Siddhartha and Yasodhara, the miracle of Sravasti, where the Buddha simultaneously arises in multiple forms, and the temptation of Mara.

Cave No. 2

The paintings that have been preserved on the walls, ceilings, and pillars of Cave 2, which lies next to Cave 1, are well-known. It is more preserved and resembles Cave 1 in appearance. The elaborate rock carvings, paintings, and the cave’s feminine theme are what make it so famous, yet the artwork is inconsistent and unfinished. This cave’s 5th-century frescoes depict students attending a school; those in the front rows are seen focusing on the instructor, while those in the rear are portrayed performing and becoming distracted.

Beginning construction in the 460s, Cave 2 (35.7 m × 21.6 m) was mostly carved between 475 and 477 CE, most likely under the sponsorship and patronage of a lady who was close to Emperor Harisena. Its porch differs greatly from Cave 1’s. Looks like even the sculptures on the façade have changed. The sturdy pillars that hold up the cave are decorated with patterns. The front porch is made up of cells with vestibules on either end that are supported by pillars.

There is a square in the middle of the hall surrounded by four colonnades that support the ceiling. There is an aisle between each arm, or colonnade, of the square that runs along the corresponding hall walls. There are rock beams both above and below the colonnades. Various decorative themes, such as ornamental, human, animal, vegetal, and semi-divine figures, are carved and painted on the capitals. Among the important sculptures is the goddess Hariti.

Her initial form was that of a child-eating demon associated with smallpox, but the Buddha transformed her into a goddess of fertility, simple childbirth, and baby protection.

Numerous publications have featured the artwork found on Cave 2’s walls and ceilings. They portray the Purna Avadhana and the stories of Hamsa, Vidhurapandita, Ruru, and Kshanti Jataka. Additional murals include the dream of Maya, Ashtabhaya Avalokitesvara, and the miracle of Sravasti.

Similar to how cave 1’s stories highlight royalty, cave 2’s stories include several strong, noble women in key roles, raising the possibility that the patron was an unidentified woman. The doorway that leads to the hall is located in the center of the back wall of the porch. A square-shaped window to let light in the inside is located on either side of the door.

Cave No. 3

Cave 3 is only the beginning of an excavation; Spink states that it was started immediately after the conclusion of the last round of work and quickly abandoned.

The sole evidence of this completed monastery is the early excavations of the pillared veranda. One of the final projects to begin at the location was the cave. Its date might be about 477 CE, right before Emperor Harisena’s unexpected demise. After clearing away a crude entryway to the hall, the work ceased.

Cave No. 4

Mathura, probably a rich devotee rather than a nobleman or royal official, was the sponsor of Cave 4, a Vihara. Given that this is the biggest vihara among the original group, it is likely that he was extremely wealthy and powerful even though he was not a public servant. Its placement at a much higher elevation may have resulted from the artists’ realization that they had a greater possibility of a big vihara at an elevated site and that the rock quality at the lower and similar level of other caves was poor.

The height of the front cells on the left side suggests that the architects intended to sculpt another sizable cistern into the rock for additional occupants to the left courtside, mimicking the arrangement on the right. This is another plausible explanation.

It is dated to the sixth century CE by the Archaeological Survey of India. By contrast, Spink dates the opening of this cave to around 463 CE, a century earlier, based on other inscriptions and the manner of construction. Cave 4’s center hall exhibits signs of a spectacular roof collapse that most likely occurred in the sixth century due to the cave’s size and natural rock faults.

Later, in an effort to get over this geological imperfection, the artists dug deeper to expose the basalt lava that was imbedded, boosting the ceiling’s height.

The cave’s floor design is square, and within is a massive statue of the Buddha standing in a preaching position, surrounded by bodhisattvas and heavenly nymphs. It is made up of an antechamber-equipped sanctum, a hypostylar hall, a verandah, and many incomplete cells. This monastery, measuring around 970 square meters (10,400 square feet) (35 m × 28 m), is the biggest of the Ajanta caves.

The door frame has beautiful carvings on either side that depict a Bodhisattva relieving the Eight Great Perils. The Avalokiteśvara litany panel is located on the back wall of the veranda. The cave’s main layout was probably compromised by the fall of its ceiling, leaving it unfinished.

With the exception of the features the sponsor deemed most significant, only the Buddha statue and the main sculptures were finished. No other features within the cave have ever been painted.

Cave No. 5

Unfinished excavation Cave 5 (10.32 × 16.8 m) was intended to be a monastery. All that remains of the architecture and sculpture in Cave 5 is the entrance frame. Indian arts from the ancient and medieval periods include feminine figures adorned with legendary Makara animals in the elaborate carvings on the frame.

Due to natural weaknesses in the sandstone, the cave’s construction was probably started about 465 CE but was later abandoned. After Asmakas began work at the Ajanta caves in 475 CE, the building was put on hold once more as the artists and patron revised the plan and concentrated on an enlarged Cave 6 that borders Cave 5.

Cave No. 6

A two-story monastery (16.85 × 18.07 m) is Cave 6. It is made up of a hall on two floors and a sanctum. The attached cells and pillars support the bottom level. There are additional auxiliary cells in the top hall. A Buddha in the teaching pose may be seen in the sanctums on both levels. The Buddha is shown in several mudras elsewhere.

Legends of the Miracle of Sravasti and the Temptation of Mara are painted on the walls on the lower level. In cave 6, just the lower level was completed. There is a shrine Buddha and several individual votive sculptures on the incomplete top level of cave 6.

During the second stage of construction, Cave 6’s bottom floor was probably the first excavation to be conducted. About four centuries after the previous Hinayana theme building, this era of Ajanta renovation signaled the beginning of the Mahayana theme and the Vakataka Renaissance period.

The top story was constructed as an afterthought, perhaps about the time when the artists and architects gave up on trying to improve the geologically faulty rock of Cave 5, which lies right next to it. The higher story was not originally intended. Both Cave 6’s top and lower levels exhibit shoddy experimenting and construction flaws. The cave painting, which is the first to depict attendant Bodhisattvas, was most likely completed between 460 and 470 CE.

Construction on the top cave likely started around 465 and advanced quickly, going far farther into the rock than the lower level.

Both floors’ walls and the sanctum’s door frame have elaborate carvings. These include subjects like apsaras, makaras, and other mythological animals, elephants in various states of action, and women waving or making welcome gestures. Cave 6’s top level is noteworthy because it depicts a devotee bowing at the feet of the Buddha, suggesting that by the fifth century, people were practicing devotional worship.

The enormous Buddha at the shrine was completed in a hurry in 477–478 CE, following the death of King Harisena, despite having an intricate throne back. Only five of the Six Buddhas of the Past are carved in the shrine antechamber of the cave, which is home to an incomplete collection of these sculptures.

This concept could have been inspired by those found in Madhya Pradesh’s Bagh Caves.

Cave No. 7

Similar in size (15.55 × 31.25 m), Cave 7 is a one-story monastery. It is made up of eight tiny monastic chambers, an octagonal pillared hall, and a sanctum. The image of the sanctum Buddha is one of preaching. Numerous artwork panels depict Buddhist themes, such as the Miracle of Sravasti and the Buddha with Nagamuchalinda.

Cave 7 features two porticos and an imposing front. Eight of two kinds of pillars support the veranda. One features a lotus capital and an octagonal base with amalaka. The other has a simple capital and an octagonal shaft in place of a base with a characteristic form. The antechamber is accessible from the veranda.

This antechamber’s left side features standing and sitting sculptures, including 25 carved images of sitting Buddhas with distinct facial expressions; the right side features 58 images of sitting Buddha reliefs in various poses, all of which are positioned on lotuses. Buddhist theology’s Miracle of Sravasti is portrayed in sculpture by these Buddhas and others on the antechamber’s inner walls.

Two hooded serpents known as nagas are depicted in the bottom row, clutching the lotus stalk in blossom. Through a door frame, the sanctuary is accessible from the antechamber. Two female figures are carved on this frame, perched on legendary sea animals known as makaras. Within the sacred space, the Buddha is seated in a cross-legged stance on a lion throne, encircled by more Bodhisattva images, two servants wearing chauris, and soaring apsaras overhead.

Cave 7 was never explored all the way down to the edge of the cliff, maybe due to rock flaws. There is no center hall; it just has the two porticos and a shrine room with an antechamber. A few cells were installed. It’s possible that the artwork in the cave was updated and changed throughout time. The initial form was finished by 469 CE, and the many Buddhas were added and painted between 476 and 478 CE, a few years later.

Cave No. 8

Another incomplete monastery measuring 15.24 x 24.64 meters is Cave 8. In the 20th century, this cave served as a generator room and storage for many years. The Archaeological Survey of India claims that this cave, which is substantially lower than other caves and conveniently located at river level, may be among the oldest monasteries. Its front is largely destroyed, most likely from a landslide. After stable engravings were disrupted by a geological fracture consisting of a mineral layer, the cave excavation proved challenging and was likely abandoned.

On the other hand, according to Spink, Cave 8 may be the oldest cave of the second phase, with its shrine being an “afterthought”. According to Spink, it could be the earliest Mahayana monastery ever unearthed in India. Since the statue has disappeared, it’s possible that it was loose rather than carved into the live rock. There are just faint remnants of the painted cave.

On the other hand, according to Spink, Cave 8 may be the oldest cave of the second phase, with its shrine being an “afterthought”. According to Spink, it could be the earliest Mahayana monastery ever unearthed in India. Since the statue has disappeared, it’s possible that it was loose rather than carved into the live rock. There are just faint remnants of the painted cave.

Cave No. 9

Caves 9 and 10 are the two chaitya, or prayer halls, from the first building phase, which lasted from the second to the first century BCE. However, both were altered toward the conclusion of the second construction period, in the fifth century CE.

Though smaller than Cave 10 (30.5 m × 12.2 m), Cave 9 (18.24 m × 8.04 m) is more intricate. This has prompted Spink to believe that Cave 9 was created around a century after Cave 10 and that Cave 10 may have originated in the first century BCE. The second era also includes the little “shrinelets” known as caves 9A through 9D and 10A. These were ordered by private citizens. The remaining shape of the Cave 9 arch indicates that its fittings were probably made of wood.

The apsidal form, nave, aisle, and apse of the cave are reminiscent of European cathedrals constructed decades later, concerning iconography, construction, and layout. There is a row of 23 pillars in the aisle. There is a vaulted ceiling. A circumambulation route encircles the stupa, which is located in the middle of the apse. The base of the stupa is tall and cylindrical. Voters are approaching the stupa on the cave’s left wall, indicating a devout custom.

Spink claims that the paintings in this cave were added in the fifth century, along with the obtrusive standing Buddhas atop the pillars. Bright paintings of the Buddha with Padmapani and Vajrapani beside him, wearing necklaces and jewels, can be seen above the pillars and behind the stupa.

Yogis, commoners, and Buddhist bhikshu are depicted approaching the Buddha with garlands and offerings, with men in dhoti and turbans wrapped around their heads. There are friezes of Jataka stories on the walls, although they probably date from the early Hinayana period of building. Certain panels and reliefs found both within and outside Cave 10 are associated with Buddhist stories, however they do not make narrative sense.

The reason for the narrative’s lack of coherence might be that these were added in the fifth century, wherever there was adequate room, by various monks and official sponsors. It is most likely because of this devotionalism and the worship hall aspect of this cave that four further shrinelets, 9A, 9B, 9C, and 9D, were erected in between Caves 9 and 10.

Cave No. 10

Dated to around the first century BCE, Cave 10, a spacious prayer hall known as Chaitya, and the neighboring Vihara Cave No. 12 are also ancient. Thus, these two caverns are among the Ajanta complex’s earliest. It has a sizable nave that divides its aisle, a series of 39 octagonal pillars supporting the central apsidal hall, and a stupa for worship at the end. There is a circumambulatory walk, or pradakshina patha, on the stupa.

This cave is important because of its size, which attests to Buddhism’s dominance in South Asia by the first century BCE and its sustained if waning, presence in India until the fifth century CE. Moreover, the cave bears several inscriptions describing various sections as “gifts of prasada” from various people, indicating that the cave was supported by the society as a whole rather than by a single monarch or high-ranking official.

Another reason Cave 10 is significant historically is because it was discovered in April 1819 by British Army commander John Smith, who made the finding known to Western audiences.

Chronology

Around the same time, a number of further caves were constructed in Western India with royal support. The sequence of these early Chaitya Caves is believed to be as follows: Cave 9 at Kondivite Caves comes first, followed by Cave 12 at Bhaja Caves, both of which precede Ajanta Cave 10.

After Ajanta Cave 10, the following caves are listed chronologically: Cave 3 at Pitalkhora, Cave 1 at Kondana Caves, Cave 9 at Ajanta (which may have been constructed approximately a century later due to its more elaborate designs), Cave 18 at Nasik Caves, and Cave 7 at Bedse Caves. The “final perfection” of the Great Chaitya at Karla Caves is the last cave.

Inscription

An interesting archeological find is a Sanskrit inscription in Brahmi writing found in Cave 10. Paleographical dating of the Brahmi characters places the inscription at the earliest Ajanta site, dating to the second century BCE. It says this:

𑀯𑀲𑀺𑀣𑀺𑀧𑀼𑀢𑀲 𑀓𑀝𑀳𑀸𑀤𑀺𑀦𑁄 𑀖𑀭𑀫𑀼𑀔 𑀤𑀸𑀦𑀁

Vasithiputasa Kaṭahādino gharamukha dānaṁ

“The Gift of a cave-façade by Vasisthiputra” Katahadi.”

— Inscription of Cave No.10.

Paintings

The paintings in Cave 10 comprise a great number of smaller late intrusive images for votive purposes, mostly Buddhas and many with donor inscriptions from individuals, as well as some that survive from the early period, many from an incomplete modernization program in the second period. they mainly avoided over-painting the “official” program; the hands of several different painters are evident, and the total number of them (including those that are now destroyed) was probably over 300.

After the best spots were taken, these were tucked away in less conspicuous positions that had not yet been painted. Many of the paintings, which span two eras, tell the Jataka stories in a clockwise manner.

Stage paintings from the Hinayana and Mahayana periods may both be distinguished, while the former are more worn and dirty from early Hinayana worship periods.

The fable of the six-tusked elephant, known as the Saddanta Jataka, and the narrative of the man who dedicates his life to helping his blind parents, known as the Shyama Jataka, are of particular interest here.

Stella Kramrisch claims that the earliest layer of the Cave 10 paintings is from around 100 BCE, and the compositional ideas of these paintings are similar to those found in Sanchi and Amaravati at the same period.

Cave No. 11

The 19.87 x 17.35 m monastery known as Cave 11 was constructed between 462 and 478. The pillars supporting the cave veranda have square bases and octagonal shafts. There are indications of floral patterns and deteriorated reliefs on the veranda ceiling.

The Buddha is portrayed with devotees forming a line to worship before him in the center panel, which is the only one that can be seen. The cave’s interior has six chambers and a hallway with a long rock bench. The Nasik Caves include stone seats that resemble these. There is a sanctuary with four cells and a Buddha reclining against an unfinished stupa at the end of another pillared verandah.

There are a few murals in the cave that depict the Buddha and Bodhisattvas. The Padmapani, a praying couple, two peafowl, and a painting of a female figure have all survived in the best shape. This cave’s sanctuary, with its circumambulation route around the seated Buddha, may be one of the last buildings at Ajanta.

Cave No. 12

Cave 12 is an early-stage Hinayana (Theravada) monastery (14.9 x 17.82 m) from the second to first century BCE, according to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). However, Spink only assigns a date of the first century BCE.

The front wall of the cave has totally fallen, causing devastation. Inside, twelve cells with two stone beds each are located on its three sides.

Cave No. 13

Another little monastery from the early era is Cave 13. It is made up of a hall with seven chambers that are all cut out of the rock and have two stone beds in each. The monks’ beds are carved out of rock in each cell. Gupte and Mahajan date both of these caves to the first and second centuries CE, two to three centuries later than ASI’s estimate.

Cave No. 14

Above Cave 13, but with dimensions of 13.43 x 19.28 meters, Cave 14 is another incomplete monastery. The framing of the front door displays sala bhanjikas.

Cave No. 15

Cave 15, measuring 19.62 × 15.98 meters, is a more comprehensive monastery that has signs of painting. The cave is made up of an antechamber, a verandah supported by pillars, and an eight-celled hall that ends in a sanctum. The sanctum Buddha is depicted in the reliefs sitting in the Simhasana position. Pigeons eating grain are carved on the entrance frame of Cave 15.

Cave 15A.

The smallest cave, cave 15A, has one cell on each side and a hall. Its entrance is immediately to the right of Cave 16’s elephant-decorated entrance. Three chambers surround a little central hall in this old Hinayana cave. The doors are embellished with an arch and rail design. It formerly had an inscription, lost to time, in an antiquated script.

Cave No. 16

Situated at a prominent location close to the center of the complex, Cave 16 was funded by Varahadeva, the minister of Vakataka monarch Harishena (r. around 475–500 CE). He adhered to the Buddhist faith.

With an inscription expressing his wish that “the entire world (…) enter that peaceful and noble state free from sorrow and disease” and reaffirming his commitment to the Buddhist faith—” regarding the sacred law as his only companion, (he was) extremely devoted to the Buddha, the teacher of the world”—he dedicated it to the monk community.

According to Spink, he was most likely a worshipper of both the Buddha and the Hindu gods, as he declares his Hindu ancestry at a neighboring cave called Ghatotkacha.

The cave was identified as the site’s entrance by the Chinese explorer Xuan Zang in the seventh century.

Cave 16, measuring 19.5 m by 22.25 m by 4.6 m, had an impact on the whole site’s design. Referred to as the “crucial cave” by Spink and other academics, it aids in establishing the chronology of the second and last phases of the intricate building of the entire cave.

The typical configuration of a main gateway, two windows, and two aisle doors may be seen in Cave 16, a Mahayana monastery. This monastery’s veranda is 19.5 m by 3 m, and its main hall has a side measuring 19.5 m, making it nearly a perfect square.

Cave 16 contains a large number of artwork. Stories contain a variety of Jataka stories, including the Sutasoma fables, Mahaummagga, and Hasti. Other frescoes show the narrative of Trapusha and Bhallika, the plowing festival, the conversion of Nanda, the miracle of Sravasti, Sujata’s offering, Asita’s visit, and the dream of Maya.

The Hasti Jataka frescoes narrate the tale of a Bodhisattva elephant who discovers that a sizable gathering of people are famished and instructs them to descend a precipice to a place where food is available. The elephant then gives himself up by leaping off the cliff, turning into food to help the humans live. The story is told in a clockwise manner in the frescoes located in the main corridor, just to the left of the entry.

The left wall of the hallway has the Mahaummagga Jataka frescoes, which depict the tale of a young Bodhisattva. After that, the story of Nanda’s conversion—the Buddha’s half-brother—can be found in the left corridor.

The narrative presented is one of the two main interpretations of the Nanda tale in the Buddhist tradition. In the version, Nanda aspires to live a sensuous life with the girl he recently got married to, and the Buddha shows him the spiritual perils of such a life by taking him to paradise and then hell.

The Nanda-related frescoes are followed in the cave by Manushi Buddhas, Buddha seated in teaching asana and dharma chakra mudra, and flying votaries carrying offerings to honor the Buddha.

Scenes from the life of the Buddha are shown on the corridor’s right wall. These include the future Buddha sitting by himself beneath a tree, Sujata bringing food to the Buddha in a begging bowl while wearing a white clothing, Tapussa and Bhalluka standing next to the Buddha after they offered wheat and honey to the Buddha as monks, and the Buddha at a plowing ceremony.

Buddha’s parents are depicted in one artwork as attempting to talk him out of becoming a monk. Another depicts the Buddha in the palace, surrounded by women in saris and men in dhotis, with his demeanor exhibiting the four indicators of impending renunciation.

Additionally, paintings depicting the future Buddha as a baby with sage Asita and rishi-like features may be found on this side of the passageway. Some of the Cave 16 paintings, according to Spink, were left unfinished.

Cave No. 17

Among the several caverns supported by Hindu Vakataka prime minister Varahadeva were Cave 17 (34.5 m × 25.63 m), Cave 16 with two enormous stone elephants at the entrance, and Cave 26 with a sleeping Buddha. An inscription in Cave 17 attests to the fact that the place was also supported by other donors, including the monarch Upendragupta.

Among the cave’s most notable and well-preserved murals are some of the largest and most intricate vihara designs. Although Cave 16 is recognized for portraying the life stories of the Buddha, Cave 17’s paintings have garnered significant attention for their narrative of the Jataka tales, which exalt human qualities. What Stella Kramrisch refers to as “lavish elegance”—a realism achieved by skilled artisans—and meticulous attention to detail are features of the storytelling.

According to Kramrisch, the ancient painters attempted to depict the wind blowing over a crop by bending it into waves, and they also used a profusion of rhythmic sequences that graphically express the metaphysical by unraveling narrative after story.

The Cave 17 monastery has several unique features, such as a colonnaded porch, many pillars, a peristyle internal hall design, a shrine antechamber tucked away deep within the cave, wider windows and doors for more light, and numerous incorporated sculptures of Indian gods and goddesses.

This monastery has a 380.53 square meter (4,096.0 square foot) hall supported by 20 pillars. According to Spink, the large-scale carving also caused mistakes while shaping the walls by removing too much rock, which caused the cave to spread out toward the back.

King Upendragupta wrote a lengthy inscription in Cave 17 explaining that he had “expended abundant wealth” on the construction of this vihara, which greatly pleased the devotees. At least five of the Ajanta caves are known to have been financed by Upendragupta overall. It’s possible that he overspent on his religious endeavors, as the Asmaka’s onslaught finally proved to be too strong for him.

There are thirty large paintings in Cave 17. Buddha is seen in Cave 17 in a variety of guises and shapes, including Vipasyi, Sikhi, Visvbhu, Krakuchchanda, Kanakamuni, Kashyapa, and Sakyamuni. Avalokitesvara, the tales of Udayin and Gupta, Nalagiri, the Wheel of Life, a panel honoring several traditional Indian musicians, and a panel detailing Prince Simhala’s journey to Sri Lanka are all shown.

The tales of the Jatakas, including Shaddanta, Hasti, Hamsa, Vessantara, Sutasoma, Mahakapi (in two versions), Sarabhamiga, Machchha, Matiposaka, Shyama, Mahisha, Valahassa, Sibi, Ruru, and Nigrodamiga, are portrayed in the narrative frescos. The depictions incorporate the social mores and cultural standards of the early first millennium.

They feature a wide range of topics, including a shipwreck, a princess getting ready, lovers having passionate moments, and a pair enjoying wine while sitting amorously together. Some frescoes include animals and attendants in the same scene in an attempt to illustrate the main characters from different sections of a Jataka story.

Cave No. 18

Cave 18 is a tiny, rectangular room measuring 3.38 by 11.66 meters that connects to another cell with two octagonal pillars. Its function is unknown.

Cave 19 (5th century CE)

Dated to the fifth century CE, Cave 19 is a worship chamber (chaitya griha, 16.05 × 7.09 m). Buddha is painted in the hall, appearing in various stances. Through what was formerly a carved chamber, one now enters this worship hall. The fact that this chamber is located before the hall indicates that the original design called for a courtyard in the mandala pattern where devotees may congregate and wait.

The entrance and façade to this courtyard, however, as well as other structures, are now lost to history. Among the caves renowned for its sculptures is Cave 19. It has Naga figures, like to those found for spiritual symbols in the ancient Jain and Hindu traditions, guarding the Buddha under a serpent canopy.

Yaksha Dvarapala is among them [in what language?] What language is this? (Guardian) pictures on the side of its vatayana (arches), indications that the ceiling was formerly painted, flying couples, sitting and standing Buddhas, and more.

The design and testing in Cave 9 served as a basis for Cave 19. Since the king and dynasty that built this cave were from the Shaivism Hindu tradition, it made a significant break from the earlier Hinayana tradition by carving a Buddha into the stupa. This decision implies that Spink must have come from “the highest levels” in the 5th-century Mahayana Buddhist establishment.

When Cave 19 was consecrated in 471 CE, it was still unfinished, despite the fact that its excavation and stupa were probably in place by 467 CE. The cave’s artistic work and completing lasted until the early 470s.

The Cave 19 Worship Hall has a beautiful front facade. A porch is supported by two circular pillars with carved garlands and fluted floral motifs. An inverted lotus leading to an amalaka serves as its capital. A devotee is kneeling at the feet of the standing Buddha in the varada hasta mudra to its left. A lady is depicted in relief on the right, one hand on her chin and the other gripping a pitcher.

Buddha sitting in mudra for meditation, above. The “Mother and Child” sculpture is located to the right of the entryway. The Buddha is seen with a begging bowl, and his son and wife are standing by him.

With fifteen pillars separating it into two side aisles and one nave, the worship hall is apsidal. The round pillars have Buddha capitals on top of a fluted shaft decorated with flower reliefs. Elephants, horses, and flying apsara friezes, which are prevalent across India, are positioned next to the Buddha in the capitals and are indicative of the Gupta Empire’s artistic style.

Sharma claims that Cave 19 could have been designed after the Karla Caves Great Chaitya, which were constructed in the second century CE, due to parallels between the two sites.

Within the worship hall, murals adorn the walls and the ceiling of the side aisles. These depict the Buddha, flowers, and the “Mother and Child” narrative once again in the left aisle.

Cave No. 20

A 5th-century monastic hall measuring 16.2 by 17.91 meters is located in Cave 20. King Upendragupta announced his intention “to make the great tree of religious merit grow” when he began work on it, according to Spink. Cave 20’s construction was done concurrently with other caves.

According to Spink, Cave 20 contains excellent workmanship, although it wasn’t given as much emphasis as Caves 17 and 19. There were periods when work on Cave 20 was discontinued, but it was resumed in the next 10 years.

A large number of the decorative and figurative sculptures in Cave 20 are comparable to those in Cave 19 and, to a lesser extent, Cave 17. This might be as a result of the three caverns’ development being overseen by the same craftsmen and architects. One of the Ajanta site’s distinctive features is the quasi-structural door frames seen in Cave 20.

According to Spink, Cave 20’s decorations are particularly inventive. One such image depicts the Buddha sitting between two cushions with “a richly laden mango tree behind him.”

Cave No. 21

Cave 21 is a hall measuring 29.56 x 28.03 meters that has a sanctuary, twelve rock-cut monastic chambers, and twelve pilastered and pillared verandahs. There are floral and animal sculptures on the pilaster. The pillars are adorned with reliefs depicting devotees kneeling with the Anjali mudra and apsaras, Nagaraja, and Nagarani.

There is proof that the hall was formerly entirely painted. The image of the sanctum Buddha is one of preaching.

Cave No. 22

Cave 22 is a tiny vihara measuring 12.72 by 11.58 meters, including four incomplete chambers and a slender veranda. It requires climbing a set of steps to access since it is dug at a higher elevation. The Buddha sits in pralamba-padasana within. Cave 22’s painted figures depict Manushi-Buddhas alongside Maitreya. On the left side of the Cave 22 veranda, there is an inscription in Sanskrit prose on a pilaster.

Though partially broken, the inscription still reads “meritorious gift of a mandapa by Jayata”, referring to Jayata’s family as “a great Upasaka” and concluding with the words “may the merit of this be for excellent knowledge to all sentient beings, beginning with father and mother”.

Cave No. 23

Similar in layout to Cave 21, Cave 23 is likewise incomplete and consists of a hall measuring 28.32 × 22.52 meters. The naga doorkeepers and the pillar decorations inside the cave are unique.

Cave 24

Though considerably bigger, Cave 24 is an incomplete version of Cave 21. After Cave 4, it has the second-largest monastic hall measuring 29.3 × 29.3 meters. The Cave 24 monastery has been crucial to the site’s scholarly investigations because it demonstrates how several labor groups accomplished their goals concurrently.

As soon as the aisle was dug out and the main hall and sanctum were being built, work on the cells started. Although the building of Cave 24 was scheduled to begin in 467 CE, it most likely began in 475 CE with assistance from Buddhabhadra. Then, in 477 CE, the sponsor King Harisena’s death brought the project to an abrupt halt.

It is noteworthy because one of the most intricate capitals can be seen on a pillar at the Ajanta site, demonstrating the artisans’ proficiency and ongoing refinement as they worked with the cave’s rock. Working in low light in a small cave, the artisans carved fourteen intricate miniature sculptures on the middle panel of the right center porch pillar.

In a similar vein, the medallion reliefs in Cave 24 depict humanoid artwork and loving couples as opposed to the flowers of the previous building. The sanctuary of Cave 24 has a sitting Buddha in pralamba-padasana.

Cave No. 25

It’s a monastery at Cave 25. Comparable in size to other monasteries, its hall (11.37 × 12.24 m) is dug at an upper level, lacks a sanctuary, and has an enclosed courtyard.

Five Centuries CE Cave 26

Similar in layout to Cave 19, Cave 26 is a worship hall (chaityagriha, 25.34 × 11.52 m). It has features of a vihara design and is substantially bigger. This large cave was provided by a monk named Buddhabhadra and his buddy, a minister who served the monarch of Asmaka, according to an inscription.

“A memorial on the mountain that will endure for as long as the moon and the sun continue” is the stated goal, along with a vision statement, according to Walter Spink’s translation. It’s possible that the architects of Cave 26 chose to emphasize sculpture over paintings because they thought stone carvings would last far longer than wall paintings.

More complex and detailed sculptures may be seen in Cave 26. One of the final caves to be discovered, ASI notes that an inscription points to the late 5th or early 6th century. An apsidal hall with side aisles for circumambulation (pradikshana) makes up the cave.

Entire Buddhist stories are carved along this walkway; three representations of the Miracle of Sravasti are located on the right ambulatory side of the aisle; and Buddhas are sitting in various mudras. The initial planners’ intentions were obstructed by the addition of several elements that were added subsequently by followers. The artwork starts on the aisle wall just to the left of the entryway.

The Mahaparinirvana of Buddha (the reclining Buddha) and the narrative known as the “Temptations by Mara” are the two main artworks. One of the temptations is being seduced by Mara’s daughters, who are seen underneath the Buddha in meditation.

They are depicted in skimpy clothing and sensual poses, with Mara’s legions positioned on both sides of the Buddha, trying to frighten him with violence and divert his attention with noise. A picture of a despondent Mara, unhappy that he could not break the austere Buddha’s determination or focus, may be seen in the upper right corner.

A stupa made out of granite sits in the middle of the apse. The stupa has a three-tiered torana above the Buddha, 18 panels on its base, 18 panels above it, and a picture of the Buddha on the front. The anda (hemispherical egg) stupa is carved with apsaras.

A nine-tiered harmika, representing the nine saṃsāra (Buddhist) heavens in Mahayana cosmology, is perched atop the dagoba. Buddhist motifs are intricately carved on the triforium, pillars, walls, and brackets. As part of the site conservation efforts, several of the severely damaged wall reliefs and pictures in this cave have been repaired.

An inscription from the late 7th or early 8th century, written by a courtier of Rashtrakuta Nanaraj (referenced in the Multai and Sangaloda plates), is located between cave 26 and its left wing. It is the final Ajanta inscription.

Cave No. 27

It’s possible that Cave 27, a monastery, was intended to be an addition to Cave 26. Its top story has largely fallen, and its two levels are damaged. The layout is akin to that of other monasteries.

Cave No. 28

Near the westernmost point of the Ajanta complex, Cave 28 is an incomplete monastery that has been partially excavated. It is inaccessible.

Cave No. 29

Located geographically between Caves 20 and 21, Cave 29 is an incomplete monastery situated at the highest point of the Ajanta complex. It is believed that it was not identified during the first numbering system establishment.

Cave No. 30

A landslide in 1956 buried the trail that led to Cave 16. Workers along the stream bed discovered a tiny aperture and votive stupa in the rubble while attempting to clean up and rebuild the path. Excavations and additional research revealed a hitherto undiscovered Hinayana monastery cave, which dates to the first and second centuries BCE.

It’s possible that Cave 30 is the earliest cave in the Ajanta complex. The cave is 3.66 m by 3.66 m and has three chambers, each with two stone beds and stone cushions on the side. There are lotus and garland sculptures on the cell door lintels.