The Voynich manuscript is a codex with illustrations that was handwritten in Voynichese, an unidentified script. It is written on vellum that has been carbon-dated to the early 1500s (1404–1438). The manuscript may have been written in Italy during the Italian Renaissance, according on stylistic research.

Though the manuscript’s origins, author, and purpose remain unclear, theories range from a script for a constructed or natural language, an unread code, cipher, or other type of cryptography, or possibly a hoax, glossolalia, reference work (such as a folkloric index or compendium), or work of fiction (such as science fiction, metafiction, speculative fiction, or fantasy) that is currently missing the necessary context and translation(s) to properly entertain or rule out any of these possibilities.

The Polish book merchant Wilfrid Voynich, who bought the manuscript in 1912, is honored in the document’s name. The text is estimated to be 240 pages long, although there may be some missing pages. Some of the pages are foldable sheets with different widths, and the text is written from left to right.

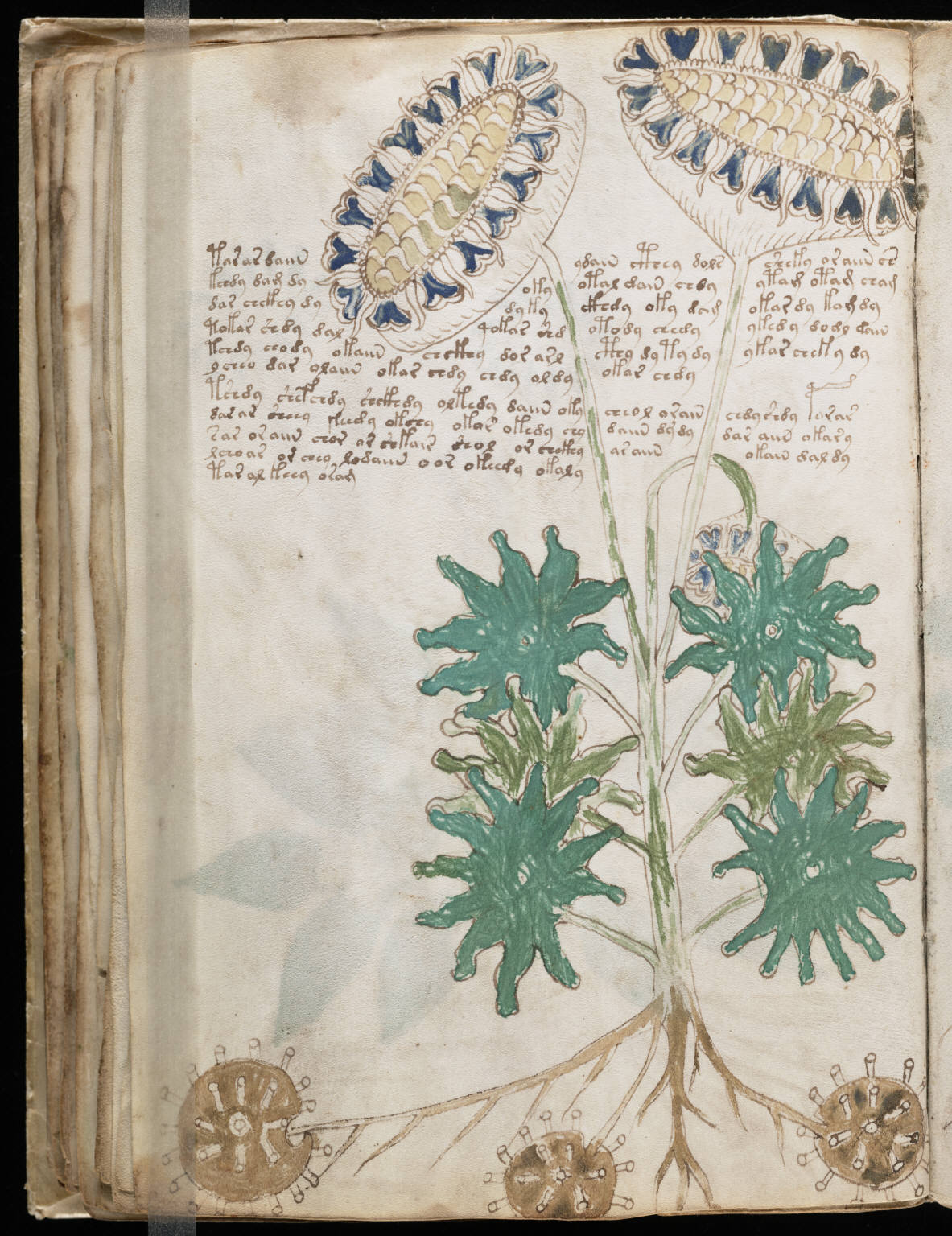

The majority of the pages feature fanciful schematics and images, some of which are badly colored. Parts of the book feature humans, imaginary vegetation, astrological symbols, and other things. It has taken place in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University since 1969. The complete work was made available online in 2020 by Yale University’s digital library.

Professional and amateur cryptographers have examined the Voynich manuscript, including American and British codebreakers from World Wars I and II. John Tiltman, Elizebeth Friedman, William Friedman, and Prescott Currier were the failed codebreakers.

None of the above theories have been independently confirmed, and the writing has never been clearly deciphered. Its meaning and origin are an enigma that has sparked research and conjecture.

Description

Codicology

Researchers have examined the manuscript’s codicology, or physical attributes. The manuscript, composed of hundreds of vellum sheets gathered into eighteen quires, measures 23.5 by 16.2 by 5 cm (9.3 by 6.4 by 2.0 in). About 240 pages altogether, however, the precise count varies depending on how the odd foldouts in the text are counted. Using a style of numbers consistent with those used in the 15th century, the quires have been numbered from 1 to 20 in various spots, and each recto (righthand) page has been numbered from 1 to 116 in the upper right corner using a style of numerals that dates from a later period.

Based on the different numbering gaps in the quires and pages, it is probable that the manuscript included at least 272 pages in 20 quires at one point in time, some of which were missing when Wilfrid Voynich bought it in 1912. There is compelling evidence that the book’s pages were initially arranged differently than they are now and that many of the bifolios have undergone several reorderings during the book’s existence.

Parchment, covers, and binding

2009 saw the University of Arizona radiocarbon date samples from different sections of the document. All analyzed samples yielded similar findings, which placed the parchment’s dating between 1404 and 1438. The parchment was made of calfskin, as confirmed by protein testing in 2014; multispectral analysis demonstrated that it had not been written on prior to the creation of the text, indicating that it is not a palimpsest. Although the paper is of mediocre quality and includes flaws like holes and splits that are typical of parchment codices, it was also meticulously prepared to the point that the skin side and the flesh side are nearly identical. They start with “at least fourteen or fifteen entire calfskins” to prepare the parchment.

Folios 42 and 47, for example, are thicker than typical parchment.

The book was owned by the Collegio Romano when the goat skin binding and covers were added. The manuscript’s first and final folios in the current sequence have insect holes, which indicates that a wooden cover existed before the subsequent covers. Edge discoloration indicates a tanned leather inside cover.

Ink

There are large, paint-colored charts and pictures on several pages. Based on contemporary investigation using polarized light microscopy (PLM), the text and figure outlines were created with a quill pen and iron gall ink. The microscopic features of the ink of the pictures, text, and page and quire numbers are comparable.

The inks were found to include significant levels of carbon, iron, sulfur, potassium, and calcium in 2009, along with trace amounts of copper and occasionally zinc, according to energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS).

Lead was not detected by EDS, although syngenite, potassium lead oxide, and potassium hydrogen sulfate were found in one of the samples examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD). The language and sketch inks’ similarities pointed to a contemporaneous origin.

Paint

The figurines were sketched in ink and then, probably at a later time, painted with colored paint, done so somewhat haphazardly. The manuscript’s paintings in the colors blue, white, reddish-brown, and green have been examined using PLM, XRD, EDS, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

- The blue paint turned out to be azurite powder with tiny amounts of cuprite copper oxide.

- Most likely, calcium carbonate and egg white are combined to make the white paint.

- The crystalline substance in the green paint may be atacamite or another copper-chlorine compound. The preliminary characteristics of the paint are copper and copper-chlorine resinate.

- The red-brown paint’s analysis revealed a red ochre including the crystal phases iron sulfide and hematite. There may be trace levels of palmierite and lead sulfide in the reddish-brown paint.

The pigments were thought to be reasonably priced.

Retouching

Jorge Stolfi, a computer scientist at the University of Campinas, pointed out that certain text and pictures had been altered, with darker ink covering an earlier, fainter writing. Numerous folios, including f1r, f3v, f26v, f57v, f67r2, f71r, f72v1, f72v3, and f73r, provide evidence for this.

Text

All of the manuscript’s pages have text on them, most of it in an undetermined language, although some also include additional Latin script writing. The 240 pages of the book are written mostly from left to right in an unidentified script. The majority of the characters are made out of just one or two basic pen strokes. A script of twenty to twenty-five characters would encompass almost all of the text; a few dozen rarer characters that appear just once or twice each would be the outliers. There is significant disagreement about whether some characters are different. Notably, there is no punctuation.

A large portion of the text is written in one column in the body of the page, occasionally with stars in the left margin and paragraph breaks and a little ragged right margin. Additional text can be found in charts or as labels next to pictures. As would be expected with written encoded language, the ductus flows smoothly, creating the illusion that the symbols were not enciphered. There is also no noticeable delay between characters.

Extraneous writing

It is believed that just a small number of words in the document were not written in the unidentified script:

- f1r: A series of Latin letters may be seen in the right margin running parallel to characters from the unidentified script. The signature of “Jacobj à Tepenecz,” which is now unreadable, is located in the bottom margin.

- f17r: A line in the upper margin written in Latin character.

f66r: The term “der Mussteil,” which is High German for “a widow’s share,” has been interpreted as a few phrases in the lower left corner next to a depiction of a naked guy. - f70v–f73v: The names of 10 months (from March to December) are written in Latin script in the astrological series of pictures in the astronomical part. The spelling of the names is reminiscent of medieval French, northwest Italian, or Iberian Peninsulan languages.

- f116v: With the exception of two words written in an unidentified script, four lines written in a somewhat deformed Latin script known as “Michitonese” The Latin script words seem to be twisted, exhibiting traits of an unidentified tongue. The words in question appear to be nonsensical in any language, despite the calligraphy bearing similarities to late 14th- and early 15th-century European alphabets.

- It’s unclear if these Latin script passages were inserted later or were a part of the original text.

Transcription

To aid in cryptanalysis, a number of transcription alphabets have been developed to translate Voynich letters into Latin characters. One such alphabet is the Extensible Voynich Alphabet (EVA), which was initially developed for use in Europe. Leading cryptographer William F. Friedman’s “First Study Group” produced the first significant one in the 1940s, transcribing each text line to an IBM punch card for machine reading.

Purpose

The manuscript’s surviving pages generally convey the idea that it was intended to be a pharmacopoeia or to include subjects related to early modern or medieval medicine. However, the enigmatic features of the pictures have sparked a lot of ideas on the history of the book, the meaning of its text, and its original intent.

Although the book’s opening part is most likely herbal, attempts to identify the plants using stylized illustrations from contemporary herbals or real specimens have not been successful. Only a handful of the plant drawings—like the maidenhair fern and a wild pansy—can be positively recognized.

With the exception of certain unlikely elements added to the missing sections, the herbal illustrations that correspond with the pharmacological sketches seem to be exact replicas of the originals. As a matter of fact, a large number of the plant illustrations in the herbal section appear to be composites, with the blooms from one species fused to the leaves of another.

When it came to harvesting herbs, bloodletting, and other traditional medicinal practices, astrological factors were often a major factor during the most likely times of the text. Apart from the obvious Zodiac symbols and one graphic that could depict the classical planets, interpretation is still speculative.

Facsimiles

Regarding the document, several books and articles have been published. Alchemist Georgius Barschius (the Latinized form of Georg Baresch; see the second paragraph under “History” above) copied the manuscript pages in 1637 and submitted them to Athanasius Kircher. Later, Wilfrid Voynich copied the pages from the text.

High-resolution digital scans were made accessible to the public online by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library in 2004, and a number of printed facsimiles were also published. A replica with scholarly notes, The Voynich Manuscript, was co-published in 2016 by Yale University Press and the Beinecke Library.

In 2017, the Spanish publisher Siloé authorized the Beinecke Library to produce a print run of 898 copies.

Multispectral scans of 10 chosen pages were released to the public in September 2024; these scans may have revealed information not discernible to the human eye.

Cultural influence

Numerous fiction pieces have been influenced by the text, including:

| Author(s) | Year | Title |

|---|---|---|

| Max McCoy | 1995 | Indiana Jones and the Philosopher’s Stone |

| Lev Grossman | 2004 | Codex |

| Scarlett Thomas | 2004 | PopCo |

| Alex Scarrow | 2011 | Time Riders: The Doomsday Code |

| Linda Sue Park | 2012 | Trust No One |

| Dominic Selwood | 2013 | The Sword of Moses |

| Deborah Harkness | 2014 | The Book of Life |

| Mircea Cartarescu | 2015 | Solenoid |

- Italian artist Luigi Serafini produced the Codex Seraphinianus, which is evocative of the Voynich manuscript and has fake text and illustrations of fictitious flora, between 1976 and 1978.

- The Voynich Cipher text, a 1995 chamber piece for chorus and ensemble by contemporary classical composer Hanspeter Kyburz, draws inspiration from the text.

- Hannah Lash was commissioned by the New Haven Symphony Orchestra in 2015 to write a symphony that was influenced by the text.

- The Book of Woo, four drawn pages influenced by the Voynich manuscript, was produced by writer Oliver Knörzer and artist Puri Andini for the 500th strip of the webcomic Sandra and Woo, which was released on July 29, 2013. Strange pictures appear next to cryptic writing on each of the four pages. The comic was featured on MTV Geek and talked about on cryptology specialist Nick Pelling’s blog, Cipher Mysteries, and on Klaus Schmeh’s blog, Klausis Krypto Kolumne. In the 2017 book Unsolved! by Craig P. Bauer [de], which explores the background of well-known ciphers, the Book of Woo was also covered. On June 28, 2018, Knörzer published the translated English text in anticipation of the 1,000th comic. This revealed the critical obfuscation involved in transforming the plain text into the invented language Toki Pona.

Some Facts About Voynich Manuscript

- The Voynich Manuscript is a mysterious handwritten book filled with illustrations and undeciphered text.

- It is named after Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish-American bookseller who purchased the manuscript in 1912.

- The manuscript is housed at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University.

- The Voynich Manuscript is written in an unknown script, often referred to as Voynichese.

- The manuscript is believed to date back to the early 15th century, around 1404–1438, based on carbon dating of the vellum.

- It contains 240 pages, though some believe there were originally 272 pages.

- The text is written on vellum, a type of parchment made from calfskin.

- The manuscript features numerous plant illustrations, but none of the plants have been positively identified.

- In addition to botanical drawings, the manuscript includes sections on astronomy, biology, cosmology, pharmaceuticals, and recipes.

- The text is written from left to right, with a consistent script that flows smoothly, indicating the scribe understood the writing system.

- The Voynich Manuscript is believed to have originated in Northern Italy, based on historical and linguistic clues.

- No one has successfully deciphered the text, and it has remained a source of fascination and mystery for centuries.

- The manuscript is sometimes called the “world’s most mysterious book” due to its undeciphered text and unknown origin.

- Some scholars believe the text could be written in a cipher or code.

- Others theorize that the manuscript is written in a constructed language, similar to Elvish or Esperanto.

- The manuscript is divided into six distinct sections, including botanical, astronomical, biological, cosmological, pharmaceutical, and recipe sections.

- The botanical section features drawings of plants with intricate root systems and leaves, none of which match known species.

- The astronomical section includes diagrams of celestial objects, stars, and zodiac signs.

- The biological section features images of naked women, often immersed in fluids or connected by elaborate tubes.

- The cosmological section contains large foldout diagrams, including complex circular designs, possibly maps or diagrams of the cosmos.

- The pharmaceutical section includes drawings of herbs and roots, along with vessels and containers for preparing medicines.

- The recipe section consists of short paragraphs, possibly instructions for creating medicinal formulas or potions.

- The manuscript is illustrated in color, with the use of green, blue, red, yellow, brown, and white pigments.

- Several hypotheses have been proposed regarding its author, but none have been confirmed.

- One theory is that the manuscript was written by Roger Bacon, a 13th-century English philosopher and scientist.

- Another theory suggests that the author could be the alchemist and physician Paracelsus.

- Some believe the manuscript is the work of a medieval hoaxer, designed to deceive scholars.

- Others speculate that the manuscript could be a herbal or medical textbook, based on the plants and pharmaceutical drawings.

- The manuscript was once owned by Emperor Rudolf II of the Holy Roman Empire, who was interested in alchemy and the occult.

- Emperor Rudolf is said to have purchased the manuscript for 600 ducats, a significant sum at the time.

- The manuscript was later owned by Georg Baresch, a 17th-century alchemist from Prague.

- In 1666, Johannes Marcus Marci, a friend of Baresch, sent the manuscript to Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit scholar, hoping he could decipher it.

- Kircher was an expert in ancient languages and had successfully deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, but he never solved the Voynich Manuscript.

- Some historians speculate that Kircher might have created the manuscript as part of his scholarly hoaxes.

- The Voynich Manuscript was largely forgotten until its rediscovery by Wilfrid Voynich in 1912.

- Wilfrid Voynich tried to decipher the text for years, but he never succeeded.

- Voynich believed the manuscript held alchemical secrets or possibly a code for transmuting base metals into gold.

- The manuscript gained widespread attention after its mention in a 1944 article by historian Ethel Voynich, Wilfrid’s wife.

- No one knows for sure whether the manuscript is a hoax, a coded message, or a genuine medieval document.

- The manuscript has been the subject of many scholarly papers and books, with numerous theories but no consensus.

- One theory posits that the manuscript is a female-centric medical text, focused on gynecology and fertility.

- Others have speculated that it might contain encoded astrological predictions or horoscopes.

- The manuscript has been analyzed with modern cryptographic techniques, but none have revealed a clear solution.

- In 2014, the manuscript was subjected to advanced imaging techniques, including multispectral scanning, to analyze the text and images more deeply.

- Some researchers believe that the Voynich manuscript’s language is an early form of shorthand.

- Linguist Jacques Guy proposed that the text could be written in an Asian language, such as Chinese, but encoded phonetically.

- In 2017, computer scientists at the University of Alberta used artificial intelligence to analyze the manuscript and suggested that the text could be Hebrew, though this is debated.

- Physical analysis shows that the manuscript’s ink and pigments are consistent with those available in the early 15th century.

- No corrections or erasures are evident in the manuscript, indicating the writer was highly skilled or familiar with the script.

- Some researchers believe that the manuscript is a form of linguistic nonsense, created to entertain or confuse readers.

- Statistical analyses of the text show patterns that resemble natural languages, but no known language fits perfectly.

- The manuscript’s illustrations are a key focus for researchers, with some believing they contain symbolic or hidden meanings.

- The plant illustrations have been a particular focus of study, with no agreement on their identity or purpose.

- The manuscript contains foldout pages, some of which are unusually large, suggesting complex diagrams or charts.

- The zodiac section includes familiar astrological symbols like Aries, Taurus, and Gemini, but the connection to the text is unclear.

- Some cryptographers believe the manuscript contains mathematical ciphers or codes hidden in the text’s patterns.

- One of the theories is that the manuscript contains medieval scientific knowledge, encoded for secrecy.

- Some researchers propose that the manuscript is the work of a single author, while others believe it could be a collaborative effort.

- The manuscript’s language remains one of the biggest challenges in decipherment, as it does not match any known script or alphabet.

- The Voynich script has been classified as isolate, meaning it is unrelated to any known languages.

- Some scholars suggest the manuscript might be written in a cipher text known only to its creators.

- The Voynich Manuscript has inspired many fictional stories, including novels, TV shows, and films.

- One theory posits that the manuscript may have been intended for mnemonic purposes, helping people memorize large amounts of information.

- The botanical drawings are often interpreted as herbals, though they bear no resemblance to real plants.

- The manuscript’s recipe section might describe alchemical or medicinal formulas, but no one has deciphered the ingredients.

- Some have proposed that the manuscript was written by a group of monks or scholars, with knowledge passed through generations.

- Alchemical symbols can be found throughout the manuscript, leading some to believe it contains hidden chemical formulas.

- Despite numerous attempts at decipherment, the Voynich manuscript remains one of the most famous unsolved mysteries in history.

- Some have speculated that the text is written backward, like Leonardo da Vinci’s notes, though this theory has not been proven.

- The manuscript’s unique alphabet contains about 20–25 characters, but there are no clear spaces between words or sentences.

- Some believe the manuscript could have been written by a mystical sect, possibly for ritual purposes.

- One theory suggests that the manuscript was an educational tool used by a medieval school for teaching herbalism or astrology.

- The Voynich manuscript has been the subject of numerous conspiracy theories, with some claiming it contains hidden knowledge about aliens or ancient civilizations.

- Some cryptologists suggest that the manuscript may contain polyalphabetic ciphers, where multiple alphabets are used to encode the text.

- Researchers continue to speculate on whether the Voynich manuscript was created by a genius or an elaborate prankster.

- The plant-like creatures in the manuscript’s illustrations could be alchemical symbols, representing transformation and growth.

- Some researchers believe the strange tubes and interconnected female figures in the biological section may represent concepts of birth or regeneration.

- The manuscript may contain layers of hidden meaning, with text and illustrations overlapping to encode complex ideas.

- The use of rare plants, such as mandrakes and dragon’s blood, in medieval manuscripts has led some to suggest herbal alchemy as a possible purpose.

- The manuscript was often stored and studied alongside other esoteric texts, including ancient grimoires and astrological works.

- Some researchers believe the Voynich Manuscript may have been deliberately designed to evade interpretation, with encrypted language, symbolism, and diagrams.

- Modern scholars have identified several distinct hands or scribes, who worked on the text, though the core script remains identical.

- Linguistic analysis shows that the text contains repetitive words and phrases, common in ritualistic or ceremonial language.

- The manuscript has been digitized and made freely available online for scholars and the public to study.

- The Voynich Manuscript has inspired countless theories, but no clear consensus has emerged.

- Some have suggested that the Zodiac illustrations are connected to almanacs or agricultural calendars.

- The manuscript’s origin could be linked to secret societies, such as the Rosicrucians or other occult groups.

- The Voynich Manuscript is one of the most studied but least understood books in history.

- Graphologists have studied the handwriting of the manuscript to identify the age and personality of the writer, but the results are inconclusive.

- The text’s structure and syntax defy typical language patterns, making it a challenge for both linguists and codebreakers.

- Some have suggested that the manuscript might contain ancient knowledge, possibly passed down from an earlier civilization.

- The Voynich Manuscript remains an object of fascination and frustration for historians, linguists, and cryptographers alike.

- The manuscript has been translated into several languages, but no version has been definitively deciphered.

- The Voynich manuscript’s illustrations are often considered fantastical, with plants and creatures that have no real-world counterparts.

- Some researchers have suggested that the manuscript was created as a noble commission, perhaps for an emperor or royal court.

- The mysterious nature of the manuscript has led some to believe it contains hidden spiritual or esoteric knowledge.

- The Voynich Manuscript has sparked debates over whether it was written by a brilliant scholar, a creative mystic, or a medieval fraudster.

- Researchers continue to attempt machine learning and AI-based techniques to decode the manuscript, with varying degrees of success.

- The manuscript’s combination of text and image suggests that it was meant to be read and interpreted visually as well as linguistically.

- The Voynich Manuscript is often compared to other undeciphered texts, like the Phaistos Disc, for its persistent mystery and historical importance.