The Illuminati (/əˌluːmɪˈnɑːti/; plural of Latin illuminatus, ‘enlightened’) is a name given to several groups, both real and fictitious. Historically, the term usually refers to the Bavarian Illuminati, an Enlightenment-era secret society founded on 1 May 1776 in the Electorate of Bavaria, whose stated goals included the promulgation of reason, science, liberty, and fraternity.

“The order of the day,” they wrote in their general statutes, “is to put an end to the machinations of the purveyors of injustice, to control them without dominating them.” The Illuminati—along with Freemasonry and other secret societies—were outlawed through edict by Charles Theodore, Elector of Bavaria, with the encouragement of the Catholic Church, in 1784, 1785, 1787, and 1790. During subsequent years, the group was generally vilified by conservative and religious critics who claimed that the Illuminati continued underground and were responsible for the French Revolution.

It attracted literary men such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Gottfried Herder, as well as the reigning Duke of Gotha and Weimar.

Later usage has applied the term “Illuminati” to various groups that are supposed to be an extension of the original Bavarian Illuminati-even though these relationships have not been proven. They are often charged with plotting control of world events by staging incidents and placing their agents in government and corporate posts in order to achieve political control, influence, and a New World Order.

A feature of some of the most common and complex conspiracy theories, the Illuminati is described as secretly running the country from behind the scenes. The character of the Illuminati has found its way into popular culture and is a regular feature in hundreds of novels, films, TV programs, comics, video games, and even music videos.

History

Origins

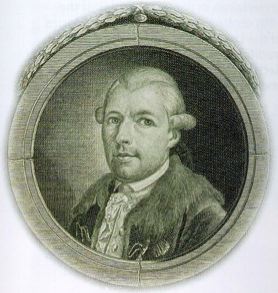

Adam Weishaupt (1748–1830) became a professor of Canon Law and practical philosophy at the University of Ingolstadt in 1773. He was the only non-clerical professor at an institution run by Jesuits, whose order Pope Clement XIV had dissolved in 1773. However, the Jesuits at Ingolstadt still controlled the finances and held some power at the university, which they continued to view as their own.

They continuously attempted to obstruct and damage the non-clerical members, especially in case of contents that they saw as liberal or Protestant within course material. From this, Weishaupt ended up being severely anti-clerical and came to the conclusion that he wanted to advance the Enlightenment ideals within a secret organization of like-minded people.

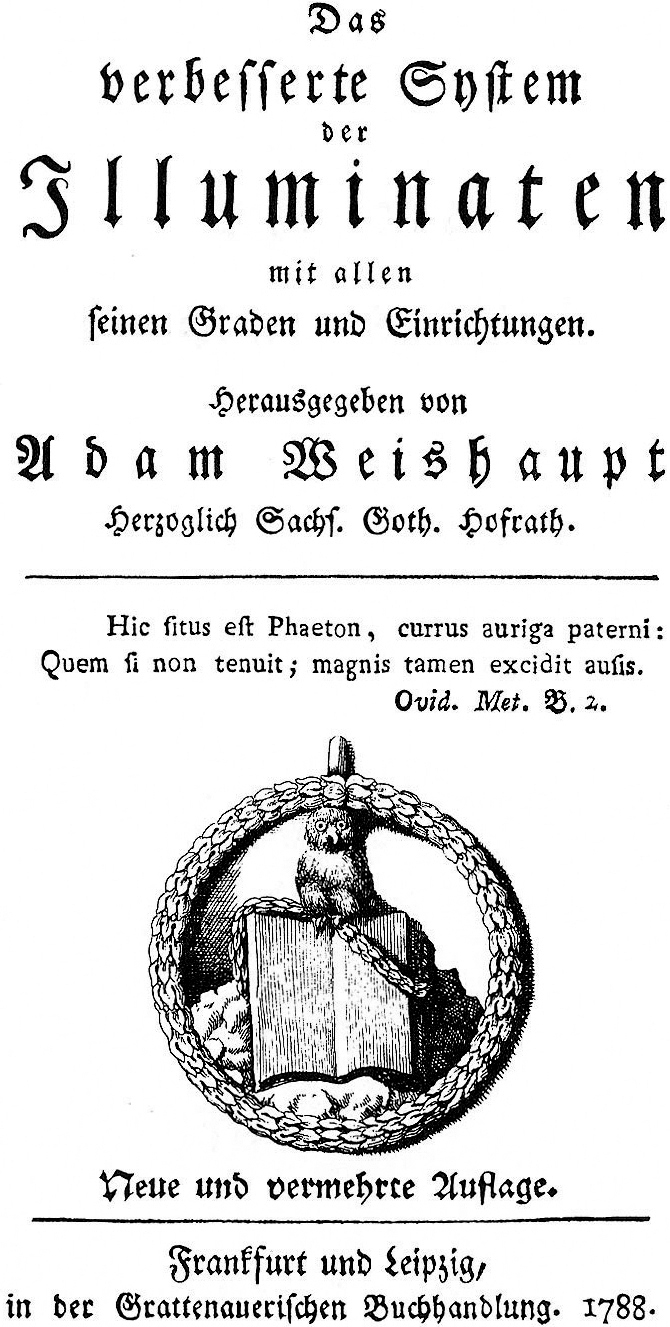

Finding Freemasonry too costly and not receptive to his plans, Weishaupt established his own organization, which was to have a system of ranks or grades similar to those in Freemasonry, but with his own agenda. He originally called the new order Bund der Perfektibilisten, or Covenant of Perfectibility (Perfectibilists), but later changed it because he felt the name sounded too unusual. On 1 May 1776, Weishaupt and four students founded the Perfectibilists, using the Owl of Minerva as their emblem.

The members used aliases within the society, with Weishaupt taking the name Spartacus. Law students Massenhausen, Bauhof, Merz, and Sutor became respectively Ajax, Agathon, Tiberius, and Erasmus Roterodamus. Weishaupt later expelled Sutor for being lazy. It became in April 1778 the Order of Illuminati, or simply Illuminatenorden, for Weishaupt had seriously taken to considering “Bee order.”

Massenhausen was the first to be actively engaged in extending the order. He is worth mentioning because while still studying at Munich soon after the formation of the order, he had enlisted Xavier von Zwack, who used to be Weishaupt’s pupil, when the latter started an important administrative career. At the time, Zwack was director of the Bavarian National Lottery.

However, his zeal proved to be damaging for Weishaupt when Massenhausen kept indulging in the practice of attempting to enrol people who were not appropriate candidates. Later on, Massenhausen’s unstable love life made him remiss.

As soon as Weishaupt transferred the Munich lodge into the hands of Zwack, he realized that Massenhausen had embezzled some subscription money and intercepted some letters between himself and Zwack. In 1778, Massenhausen graduated and moved out of Bavaria; he then lost interest in the order completely. The order by this time had a nominal membership of twelve.

With Massenhausen gone, Zwack quickly went about recruiting the older and influential members. Weishaupt was most keen to recruit Hertel, his childhood friend, who was also a canon at the Frauenkirche in Munich. By the end of summer 1778, the order had 27 members, scattered across five commands: Munich or Athens, Ingolstadt or Eleusis, Ravensberg or Sparta, Freysingen or Thebes, and Eichstaedt or Erzurum.

During this early period, there were three grades: Novice, Minerval, and Illuminated Minerval, and only the Minerval grade involved a complicated ceremony. In that ceremony, the candidate was initiated into secret signs and received a password. A system of mutual espionage made possible for Weishaupt to be aware of the activities and character of all his members.

He could promote his favorites to positions on the ruling council, or Areopagus. Some initiates were permitted to initiate others, and these were called Insinuants. Christians of good character were actively sought, but Jews, pagans, women, monks, and members of other secret societies were specifically excluded. Favored candidates were typically rich, docile, willing to learn, and aged between 18 and 30.

Transition

After failing to dissuade some of his members from joining the Freemasons, Weishaupt decided to join the older order in order to acquire material for expanding his own rituals. By early February 1777, he had been initiated into the “Prudence” lodge of the Rite of Strict Observance. But after careful progress through the three degrees of “blue lodge” masonry, there was nothing apparent on this side of the veil to inform Zwack of the inner secrets he hoped to explore.

In the following year, a priest named Abbé Marotti told Zwack that these inner secrets were founded on knowledge of the older religion and of the primitive church. Zwack convinced Weishaupt that their own order should establish friendly relations with Freemasonry and seek permission to set up their own lodge. By December 1778, the addition of the first three degrees of Freemasonry was considered a secondary project.

With little trouble, a warrant was secured from the Grand Lodge of Prussia, known as the Royal York for Friendship, and the new lodge was named Theodore of the Good Council, intended to flatter Charles Theodore, Elector of Bavaria. It was founded in Munich on 21 March 1779 and soon filled with Illuminati members. The first master of the lodge, a man named Radl, had been persuaded to return to Baden, and by July, Weishaupt’s order seized the lodge.

The next step was to gain independence from their Grand Lodge. Theodore lodge achieved this by establishing masonic relations with the Union lodge in Frankfurt, which was a lodge affiliated to the Premier Grand Lodge of England. Theodore lodge could then claim independent recognition and declare its independence. As a new mother lodge, it could then establish lodges of its own. The recruitment efforts among the Frankfurt masons also brought into the fold the allegiance of Adolph Freiherr Knigge.

Reform

Adolph Knigge

In late 1780, Knigge was recruited by Costanzo Marchese di Costanzo, an infantry captain in the Bavarian army and fellow Freemason, at a convention of the Rite of Strict Observance. Already well into his twenties, Knigge had risen through the highest initiatory grades of his order and had come with his own grand plans for reform. But, however, when his plan didn’t attract any response, he became very interested to know that the order he was keen on founding was already there.

Knigge and three of his friends became keenly interested to learn more about this order. To this end, Costanzo introduced them to material related to the Minerval grade. The instructional material for this grade was “liberal” literature, banned in Bavaria but highly known in the Protestant German states.

While Knigge’s three companions gave up and turned their backs on Costanzo, Knigge’s persistence was rewarded in November 1780 with a letter from Weishaupt. Knigge’s connections both inside and outside of Freemasonry made him an ideal recruit.

For his part, Knigge was flattered by the attention and drawn to the order’s stated aims of education and protecting mankind from despotism. Weishaupt acknowledged and pledged to support Knigge’s interest in alchemy and the “higher sciences.” In response, Knigge outlined his plans for reforming Freemasonry, as the Strict Observance began to question its own origins.

Weishaupt entrusted Knigge with recruitment before he was allowed into the higher ranks of the order. Knigge accepted this, with the condition that he could select where he wanted to recruit; many other masons were attracted by Knigge’s description of the new masonic order, and these were enrolled in the Minerval grade of the Illuminati.

At this juncture, Knigge seemed to believe in the “Most Serene Superiors” that Weishaupt professed to be serving, but his inability to explain anything at all about the higher degrees of the order became increasingly embarrassing.

In delaying to offer assistance, Weishaupt gave Knigge an additional task. With material furnished by Weishaupt, Knigge wrote pamphlets portraying the activities of the outlawed Jesuits, which he presented as proof of how they persisted and recruited new members, especially in Bavaria. Meanwhile, his inability to satisfactorily respond to the queries of his recruits regarding the higher grades was threatening to make his position untenable.

He complained to Weishaupt about these matters. In January 1781, threatened by the loss of Knigge and his masonic recruits, Weishaupt finally admitted that the superiors and the supposed antiquity of the order were fabrications, and that the higher degrees had yet to be written.

If Knigge had expected to learn the promised deep secrets of Freemasonry in the higher degrees of the Illuminati, he was surprisingly calm about Weishaupt’s revelation. Weishaupt promised Knigge a free hand in creating the higher degrees and also agreed to send him his own notes. Knigge, for his part, welcomed the opportunity to use the order as a platform for his own ideas.

He believed his new approach would make the Illuminati more attractive to prospective members in the Protestant princedoms of Germany. In November 1781, the Areopagus advanced Knigge 50 florins to travel to Bavaria, which he did by way of Swabia and Franconia, meeting and enjoying the hospitality of other Illuminati members along the way.

Internal problems

The order had now developed profound internal divisions. In July 1780, the Eichstaedt command had formed an autonomous province and a rift was growing between Weishaupt and the Areopagus, who found him stubborn, dictatorial, and inconsistent. Knigge fitted readily into the role of peacemaker.

In discussion with the Areopagus and Weishaupt, Knigge identified two areas which were problematic. Weishaupt’s focus on targeting university students meant that the senior positions in the order often had to be taken up by younger men with little practical experience. Such generalizing of the initial anti-Jesuit ethos has led to what Knigge knew would become a problem – an anti-religious sentiment that opposed the order now sought to recruit senior Freemasons.

Knigge felt keenly the stifling grip of conservative Catholicism in Bavaria and understood the anti-religious feelings that this produced in the liberal Illuminati, but he also saw the negative impression these same feelings would engender in Protestant states, inhibiting the spread of the order in greater Germany. Both the Areopagus and Weishaupt felt powerless to do anything less than give Knigge a free hand.

He had the contacts within and outside of Freemasonry that they needed, and he had the skill as a ritualist to build their projected gradal structure, where they had ground to a halt at Illuminatus Minor, with only the Minerval grade below and the merest sketches of higher grades. The only demands made on him were to publish the innermost secrets of the highest grades, and that his new grades required approval.

Meanwhile, the scheme to propagate Illuminatism as a legitimate branch of Freemasonry had stalled. While Lodge Theodore was now under their control, the chapter of “Elect Masters” attached to it only had one member from the order and still had a constitutional superiority to the craft lodge controlled by the Illuminati.

The chapter would have been hard to convince to succumb to the Areopagus and was indeed a very strong barrier to Lodge Theodore becoming the first mother-lodge of new Illuminated Freemasonry. An alliance treaty was signed between the order and the chapter, and by the end of January 1781, four daughter lodges had been founded, but independence was not what the chapter was after.

Costanza wrote to the Royal York, pointing out the disparity between the fees dispatched to their new Grand Lodge and the service they had received in return. The Royal York, unwilling to lose the revenue, offered to confer the “higher” secrets of Freemasonry on a representative that their Munich brethren would dispatch to Berlin.

Costanza thus set off for Prussia on 4 April 1780, instructed to negotiate a reduction in Theodore’s fees while he was there. On the way, he managed to get into an argument with a Frenchman over a lady with whom they were sharing a carriage. The Frenchman sent a message ahead to the king, some time before they reached Berlin, denouncing Costanza as a spy. He was only released from prison with the assistance of the Grand Master of Royal York and expelled from Prussia having achieved nothing.

New system

Knigge’s initial plan to obtain a constitution from London would, they realized, have been seen through by the chapter. Until such time as they could take over other masonic lodges that their chapter could not control, they were for the moment content to rewrite the three degrees for the lodges which they administered.

On 20 January 1782, Knigge tabled his new system of grades for the order. The classes are broken down as follows:

- Class I – The nursery, which contains the Noviciate, the Minerval, and the Illuminatus minor.

- Class II – The Masonic degrees. The three “blue lodge” degrees of Apprentice, Fellow and Master were distinguished from the higher “Scottish” degrees of Scottish Initiate and Scottish Knight.

- Class III: The Mysteries. The lower mysteries were ranked as Priest and Prince, which were followed by the higher mysteries ranked as Mage and King. Very likely, these rituals for higher mysteries were never written.

Attempts at expansion

Knigge’s recruitment from German Freemasonry was far from random. He targeted the masters and wardens, the men who ran the lodges, and were often able to place the entire lodge at the disposal of the Illuminati. In Aachen, Baron de Witte, master of Constancy lodge, caused every member to join the order. In this manner, the order spread very rapidly in central and southern Germany and gained foothold in Austria. Entering into the Spring of 1782, a handful of students who had initially started the order had grown into about 300 members, where only 20 of the newcomers were students.

In Munich, there was tremendous governmental change in Lodge Theodore in the first half of 1782. In February, Weishaupt had suggested that he divide the lodge into two: that the Illuminati continue on their own, while the chapter retain whatever remaining traditionalists might take to their continuation of Theodore.

It was now that the chapter, out of the blue, capitulated, and the Illuminati gained absolute control of both lodge and chapter. In June, lodge and chapter sent letters to Royal York severing relations due to their faithfulness in paying for recognition and Royal York’s failure to provide any instruction into the higher grades.

Neglect of Costanza, failure to defend him from malicious charges or even prevent his expulsion from Prussia, was also cited. They had made no effort to provide Costanza with the promised secrets and the Munich masons now suspected that their brethren in Berlin relied on the mystical French higher grades which they sought to avoid. Lodge Theodore was now independent.

The Rite of Strict Observance was now at a critical stage. Its nominal leader was Prince Carl of Södermanland (later Charles XIII of Sweden), openly suspected of trying to absorb the rite into the Swedish Rite, which he already controlled. The German lodges looked for leadership to Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Suspicion turned into open contempt when it came out that Carl looked upon the Stuart heir to the British throne as the true Grand Master and lodges of the Strict Observance all but ignored their Grand Master. This was the reason behind the Convent of Wilhelmsbad.

Convent of Wilhelmsbad

Postponed from 15 October 1781, the last convention of the Strict Observance finally opened on 16 July 1782 in the spa town of Wilhelmsbad on the outskirts of (now part of) Hanau. Ostensibly a conference on the future of the order, the 35 delegates were well aware that the Strict Observance as then constituted was doomed and that the Convent of Wilhelmsbad would be a fight over the pieces between the German mystics, under Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and their host Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, and the Martinists, under Jean-Baptiste Willermoz.

The only two voices that criticized this mystical higher grade were Johann Joachim Christoph Bode, who abhorred Martinism, and whose speculative alternatives for the most part were still in flux, and Franz Dietrich von Ditfurth, a judge of Wetzlar and master of the Joseph of the Three Helmets lodge there, who had already been admitted to the Illuminati. Ditfurth publicly campaigned for a return to the basic three degrees of Freemasonry, which was the least likely outcome of the convention. The mystics already had coherent plans to replace the higher degrees.

With no coherent alternative to the two strands of mysticism, the Illuminati was able to step forward as a viable option. Ditfurth, spurred on and helped along by Knigge, now empowered to act for the order, became the spokesman for the Illuminati. Knigge’s plan had originally been to offer an alliance between the two orders, but Weishaupt turned down the offer, deeming it unnecessary to ally himself with a dying order. His new plan was to recruit the masons opposed to the “Templar” higher degree of the Strict Observance.

At the convent, Ditfurth frustrated the efforts of Willermoz and Hesse to institute their own higher grades by demanding that full details of such degrees be disclosed to the delegates. Frustrated, the German mystics enrolled Count Kollowrat with the Illuminati with a view to later affiliation. Ditfurth’s own agenda was to substitute all the higher degrees with just one fourth degree, with no pretensions to greater masonic revelations. Finding no support for his scheme, Ditfurth quit the convent prematurely, writing to the Areopagus that he expected nothing good from the assembly.

The Convent of Wilhelmsbad tried to please everyone: they renounced the Templar origins of their ritual, while retaining the Templar titles, trappings, and administrative structure. At its head, Charles of Hesse and Ferdinand of Brunswick remained in office, but, at least in practice, virtually independent lodges stand here.

The Germans also adopted the name of the French order of Willermoz, les Chevaliers bienfaisants de la Cité sainte (Good Knights of the Holy City), and some Martinist mysticism was imported into the first three degrees, which were now the only essential degrees of Freemasonry.

Crucially, individual lodges of the order were now allowed to fraternize with lodges of other systems. The new “Scottish Grade” instituted with the Lyon ritual of Willermoz was not obligatory, and each province and prefecture was free to decide what, if anything, happened after the three craft degrees. Finally, in an attempt to demonstrate that something had been accomplished, the convent legislated at length on etiquette, titles, and a new numbering for the provinces.

Aftermath of Wilhelmsbad

What the Convent of Wilhelmsbad actually accomplished was the death of the Strict Observance. It renounced its own origin myth, along with the higher degrees that bound its highest and most influential members. It abolished the strict control which had kept the order united and alienated many Germans who mistrusted Martinism. Bode, who was repelled by Martinism, immediately entered negotiations with Knigge and finally joined the Illuminati in January 1783. Charles of Hesse joined the following month.

Knigge’s initial attempts at an alliance with the intact German Grand Lodges proved unsuccessful, but Weishaupt was undeterred. He offered a new federation where all of the German lodges would operate an agreed, unified system in the essential three degrees of Freemasonry and leave it to their own devices as to which, if any, system of higher degrees they wanted to pursue. This would be a federation of Grand Lodges, and members would be free to visit any of the “blue” lodges in any jurisdiction.

All lodge masters would be elected, and no fees would be paid to any central authority whatsoever. Groups of lodges would be subject to a “Scottish Directorate,” composed of members delegated by lodges, to audit finances, settle disputes, and authorize new lodges. These in turn would elect Provincial Directorates, who would elect inspectors, who would elect the national director.

Thus, this would correct the contemporary imbalance of the German Freemasonry, which ensured that the basic masonic ideology of equality persisted only at the lower three degrees known as the “symbolic” degrees, while the elites dominated the several schemes of higher degree systems by expending on studies in alchemy and mysticism.

It was also to Weishaupt and Knigge a means to spread Illuminism through all German Freemasonry. They meant to make their new federation, with its concentration on the basic degrees, purge all loyalty to Strict Observance, in favor of the “eclectic” system of the Illuminati.

The circular announcing the new federation outlined the faults of German Freemasonry, stating that unsuitable men with money were often admitted based on their wealth, and that the corruption of civil society had infected the lodges. Having called for the de-regularization of the higher degrees of the German lodges, the Illuminati now declared their own, from their “unknown Superiors.”

Lodge Theodore, freshly independent from Royal York, constituted themselves as a provincial Grand Lodge. Knigge, in a letter to all the Royal York lodges, now branded that Grand Lodge decadent. Their Freemasonry had supposedly been corrupted by the Jesuits. Strict Observance was now assailed as an invention of the Stuarts, destitute of every moral virtue.

The Zinnendorf rite of the Grand Landlodge of the Freemasons of Germany was also suspicious because its author was in league with the Swedes. This direct attack had an opposite effect to that which Weishaupt desired, offending many of its readers. The Grand Lodge of the Grand Orient of Warsaw, which governed Freemasonry in Poland and Lithuania, was content to join the federation only as far as the first three degrees.

Their desire for independence had prevented them from joining the Strict Observance and would now prevent them from joining the Illuminati, whose aim to annex Freemasonry was based on their own higher degrees. By the end of January 1783, the masonic contingent of the Illuminati had seven lodges.

It was not only the clumsy appeal of the Illuminati that left the federation short of members. Lodge Theodore was newly formed and could hardly command the respect that older lodges would have. Above all, however, the Freemasons most likely to be drawn to the federation saw the Illuminati as a useful ally against the mystics and Martinists, but prized their own liberty too highly to get caught in another restrictive organization. Even Ditfurth, said representative of the alleged Illuminati faction at Wilhelmsbad, had taken upon himself to forward the agenda for this convent.

The non-mystical Frankfurt lodges formed an “Eclectic Alliance,” which was almost indistinguishable in constitution and aims from the Illuminati’s federation. Far from viewing this as a threat, after some discussion, the Illuminati lodges joined the new alliance. Three Illuminati now sat on the committee charged with writing the new masonic statutes.

Apart from strengthening relations among the three lodges, the Illuminati would not appear to have benefited from this move. Ditfurth, who had discovered a masonic organization working towards his own ambitions for Freemasonry, did not care to devote much time to the Illuminati after his adherence to the Eclectic Alliance. In reality, the formation of the Eclectic Alliance had foiled all the machinations of the Illuminati for inculcating its own doctrine through Freemasonry.

Zenith

Though their visions of Freemason-based mass recruiting had been blocked, the group continued to sign up with efficiency at an individual level. Upon Charles Theodore succession in Bavaria, it even liberalized policies and views at the beginning; then the clergy along with the courtiers who defend their respective strength and prestige persuaded a weak-minded King to go in reverse; with this repression back again liberal opinion in Bavaria was forced inside.

This created a general sense of resentment of the monarch and the church in the educated classes, which proved a perfect recruiting ground for the Illuminati. Several Freemasons from Prudence lodge, being dissatisfied with the Martinist rites of the Chevaliers Bienfaisants, joined Lodge Theodore, which established itself in a gardened mansion that housed their library of liberal literature.

Illuminati circles elsewhere in Germany increased. Some gained only small numbers, but the circle in Mainz nearly doubled from 31 to 61. Reaction to state Catholicism brought gains in Austria, and footholds were established in Warsaw, Pressburg (Bratislava), Tyrol, Milan, and Switzerland.

The number of verifiable members at the end of 1784 is approximately 650. Weishaupt and Hertel later reported a figure of 2,500. The higher figure is largely accounted for by the inclusion of members of masonic lodges that the Illuminati claimed to control, but it is likely that the names of all the Illuminati are not known, and the true figure lies somewhere around 1,300.

The importance of the order lay in its successful recruitment of the professional classes, such as churchmen, academics, doctors, and lawyers, as well as its more recent acquisition of powerful benefactors. Enrolled were Karl August, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg with his brother and later successor August, Karl Theodor Anton Maria von Dalberg, governor of Erfurt, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (already mentioned), his chief assistant in masonic matters, Johann Friedrich von Schwarz, and Count Metternich of Koblenz.

Other prominent members included Count Brigido, governor of Galicia, Count Leopold Kolowrat, chancellor of Bohemia with his vice-Chancellor Baron Kressel, Count Pálffy von Erdöd, chancellor of Hungary, Count Banffy, governor and provincial Grand Master of Transylvania, Count Stadion, ambassador to London, and Baron von Swieten, minister of public education.

There were significant failures. Johann Kaspar Lavater, the Swiss poet and theologian, rejected Knigge. He felt that the order’s humanitarian and rationalist objectives could not be attained through secret means. In addition, he thought that the impulse of a society to enroll members would drown out its founding principles. Christoph Friedrich Nicolai, the Berlin writer and bookseller, became disillusioned after joining. He found the purposes chimeric and felt the use of Jesuit methods in trying to realize the purposes to be dangerous. He stayed within the order, but did not collaborate in its efforts at recruitment.

Some Mysteries related to the Illuminati

1. What Was the Original Purpose of the Illuminati?

The Illuminati, formally known as the Bavarian Illuminati, was founded in 1776 by Adam Weishaupt in Bavaria, Germany. The group’s original purpose was to promote Enlightenment ideals, such as reason, secularism, and the separation of church and state, as well as to challenge the influence of the religious and political authorities of the time. The Illuminati aimed to cultivate a society of free thinkers who could work together to dismantle oppressive systems and promote equality, liberty, and fraternity. However, because of their secretive nature, the group quickly became the subject of intrigue, and many speculated that their real intentions were far more sinister.

Initially, the Illuminati’s goal was to infiltrate existing institutions, particularly Freemasonry, in order to spread their ideas. The society sought to replace superstition and religious dogma with rationalism and progressive thought. Despite their ideals, the Illuminati quickly attracted suspicion from religious and political leaders, who saw them as a threat to the established order. Over time, the society was suppressed and officially disbanded in 1785, but its mythos has lived on in conspiracy theories and pop culture.

2. How Did the Illuminati End?

The Illuminati officially ended in 1785 when the Bavarian government, led by Charles Theodore, issued an edict that outlawed secret societies, including the Illuminati. The society was already facing growing scrutiny from both religious authorities and the state. Weishaupt, its founder, was forced into exile, and many of its members went into hiding or joined other secretive groups. Although the Illuminati was no longer an active organization after 1785, the group’s influence and mythology lived on in both conspiracy theories and the historical imagination.

Some argue that the Illuminati was never truly disbanded but instead went underground, continuing its activities in secrecy. Others believe that the society’s ideals and members infiltrated other organizations, such as Freemasonry and various political movements, allowing the Illuminati’s influence to persist in different forms. The ambiguity surrounding its disbandment has fueled numerous speculations about the continued existence of the Illuminati and their supposed control over world events.

3. Did the Illuminati Really Control World Events?

One of the most enduring conspiracy theories surrounding the Illuminati is the belief that the society has secretly controlled global events for centuries. According to this theory, the Illuminati is said to have infiltrated governments, banks, and other powerful institutions, subtly guiding the course of history to further their own agenda. Proponents of this idea claim that the Illuminati orchestrated key historical moments, such as revolutions, wars, and political upheavals, with the aim of establishing a “New World Order” under their control.

While there is no concrete evidence to support these claims, the idea that secret societies manipulate world events has remained a popular subject of speculation. The Illuminati’s association with Freemasonry, the French Revolution, and the rise of powerful financial institutions has led many to speculate that the group played a key role in shaping modern history. However, most historians dismiss these theories as unfounded, pointing to the lack of verifiable evidence for any grand conspiracy.

4. How Did the Illuminati Become Linked to Freemasonry?

From its inception, the Illuminati sought to infiltrate existing secret societies, and Freemasonry was seen as an ideal vehicle for their ideas. The Illuminati used the structure of Freemasonry to expand its influence, recruiting members from within the Masonic lodges. This connection between the Illuminati and Freemasonry has been the source of much speculation, as many people have associated the two organizations in conspiracy theories about world domination.

The Illuminati’s goal within Freemasonry was to promote Enlightenment ideals while supplanting older, more religious practices with rationalism and secularism. As the Illuminati grew within Freemasonry, tensions developed between the two groups, with some members of the Masonic lodges growing suspicious of the Illuminati’s aims. Although the Illuminati was eventually expelled from many Masonic lodges, the association between the two organizations has remained a key element in the mythos surrounding the Illuminati.

5. Who Were the Key Figures in the Illuminati?

Adam Weishaupt is perhaps the most well-known figure associated with the Illuminati. As the founder of the society, Weishaupt’s vision of an enlightened, secular society was the driving force behind the organization. Weishaupt was a professor of canon law at the University of Ingolstadt, and he used his academic background to recruit intellectuals, Freemasons, and other influential figures to the Illuminati’s cause. However, his leadership was not without challenges, and internal disagreements, as well as external pressure, eventually led to the group’s downfall.

Other key figures in the Illuminati included Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the famed German writer and philosopher, although it is debated whether he was an official member or simply sympathetic to the group’s ideas. Other notable members included Baron Adolf von Knigge, a prominent German writer and Freemason who played a crucial role in expanding the Illuminati’s influence, as well as influential figures within the Masonic lodges in Europe.

6. What Happened to the Illuminati After 1785?

While the Illuminati was officially disbanded in 1785, theories about the society’s continued existence have persisted for centuries. Some believe that the group went underground, continuing its activities in secret while infiltrating other powerful organizations such as Freemasonry, the French Revolution, and even major banking institutions. Others claim that the Illuminati’s members simply dispersed into different political and intellectual movements, continuing to push for Enlightenment ideals in less overt ways.

Despite the lack of concrete evidence for any continued activity by the Illuminati, their image as a shadowy force operating behind the scenes has been perpetuated by conspiracy theorists. Some believe that the Illuminati’s true agenda—establishing a New World Order—remains in play, while others argue that the organization has become obsolete in the modern world. Nonetheless, the legend of the Illuminati continues to captivate the imagination of many.

7. What Role Did the Illuminati Play in the French Revolution?

One of the most common conspiracy theories about the Illuminati is that they played a significant role in orchestrating the French Revolution. Proponents of this theory claim that the Illuminati, in collaboration with other secret societies, sought to overthrow the French monarchy and establish a new, rationalist government based on Enlightenment principles. While some historical evidence suggests that many members of the French Revolution were influenced by Enlightenment ideas, there is no direct proof linking the Illuminati to the revolution.

The French Revolution was undoubtedly shaped by a number of intellectual movements, including Enlightenment philosophy and the influence of Freemasonry. However, the idea that the Illuminati directly engineered the revolution remains highly speculative. Many historians argue that the revolution was driven by socio-political factors, such as economic inequality and the failure of the monarchy, rather than the machinations of a secret society.

8. What Was the Illuminati’s Connection to the “New World Order”?

The concept of a “New World Order” is often linked to the Illuminati in conspiracy theories. According to these theories, the Illuminati seeks to establish a global government controlled by a small elite, with the aim of subjugating the masses and eliminating national sovereignty. This idea has become a central tenet of modern conspiracy theorists, who believe that world events—such as economic crises, wars, and political shifts—are part of a grand plan orchestrated by the Illuminati to bring about this global order.

Despite the popularity of this theory, there is no evidence to suggest that the Illuminati ever had such a far-reaching agenda. The Illuminati’s original goal was more focused on promoting secularism and Enlightenment ideals, rather than creating a global government. Nevertheless, the association between the Illuminati and the concept of a New World Order has persisted, in part due to the group’s secrecy and the enduring fascination with its supposed influence.

9. How Did the Illuminati Influence Pop Culture?

Over the centuries, the Illuminati has become a staple of popular culture, appearing in countless books, movies, and television shows. The group’s secretive nature and association with conspiracy theories have made them an alluring subject for storytellers and filmmakers. From Dan Brown’s Angels and Demons to films like The Da Vinci Code, the Illuminati is often depicted as a shadowy organization pulling the strings behind major global events.

This portrayal of the Illuminati as a powerful, secretive group has further fueled conspiracy theories and public fascination with the society. Despite the lack of historical evidence linking the Illuminati to modern-day events, its place in popular culture continues to thrive, with the group often symbolizing the hidden forces of power and control.

10. Are There Any Real-World Illuminati Groups Today?

Despite the historical disbandment of the Bavarian Illuminati in 1785, rumors and conspiracy theories about modern-day Illuminati groups persist. Some claim that secret societies operating under the same name still exist today, working behind the scenes to manipulate world events. These theories often point to influential figures in politics, finance, and entertainment as potential members of the Illuminati.

However, there is no verifiable evidence to support the existence of any modern Illuminati groups. Most historians view the modern conception of the Illuminati as a myth, perpetuated by conspiracy theorists and popular media. Nevertheless, the notion of a secretive, all-powerful society continues to captivate the imagination of those who believe that powerful elites are controlling the world from the shadows.

11. How Did the Illuminati Influence Political Revolutions?

The role of the Illuminati in political revolutions, particularly in the French and American revolutions, remains a topic of intense debate. Some conspiracy theorists argue that the Illuminati secretly orchestrated these revolutions to dismantle monarchies and establish a new world order. They point to the Enlightenment ideals that the Illuminati espoused, which seemed to align with the calls for liberty and equality in these revolutions.

However, historians have not found definitive evidence linking the Illuminati to the leadership or the ideological foundation of these revolutions. While many key figures in the revolutions were influenced by Enlightenment thought, which the Illuminati promoted, the claim that the Illuminati orchestrated these events is more speculative. Some scholars suggest that while individual Illuminati members may have participated in the revolutions, their role was likely more incidental rather than orchestrated.

12. Was the Illuminati Ever Truly Suppressed?

The Illuminati was officially suppressed in 1785 by the Bavarian government, led by Charles Theodore. Weishaupt and other key members were forced to go into hiding, and the organization was declared illegal. However, the idea that the Illuminati was completely eradicated has been questioned. Some believe that the group merely went underground, continuing to operate in secret, influencing events from the shadows.

Despite the official suppression, there are accounts suggesting that Illuminati-like organizations persisted, and some even claim that the Illuminati still exists today, albeit in a more covert form. Conspiracy theories often claim that the Illuminati continues to exert control over global politics, economics, and even entertainment. However, the lack of concrete evidence means these theories remain speculative, and most historians agree that the original Illuminati ceased to exist after its suppression.

13. What Was the Relationship Between the Illuminati and the Freemasons?

The relationship between the Illuminati and Freemasonry has long been a subject of intrigue. The Illuminati, founded by Adam Weishaupt, initially sought to infiltrate Freemasonry in order to spread its ideas of Enlightenment rationalism. Many early Illuminati members were also Freemasons, and some lodges provided fertile ground for recruiting new members.

However, tensions eventually arose between the two organizations. While both groups shared certain philosophical goals, such as the promotion of secularism and the rejection of religious authority, the Illuminati’s secretive nature and its desire to control Freemasonry’s higher degrees led to conflicts. Many Freemasons viewed the Illuminati as a threat to the autonomy of their lodges, and by the late 1780s, the two organizations were increasingly at odds, with Freemasonry distancing itself from the Illuminati.

14. Why Did the Illuminati Target the Catholic Church?

The Catholic Church was one of the Illuminati’s primary targets, as the order sought to promote a secular society free from religious influence. Weishaupt and other members of the Illuminati were strongly critical of the Catholic Church, viewing it as a powerful institution that perpetuated ignorance, superstition, and authoritarianism. They believed that the Church hindered intellectual progress and stifled individual freedoms.

The Illuminati’s critique of the Church was aligned with the broader Enlightenment movement, which advocated for the separation of church and state. By infiltrating various secret societies, the Illuminati aimed to replace religious dogma with reason and scientific thought. The animosity between the Illuminati and the Catholic Church was so strong that it contributed to the Bavarian government’s decision to suppress the Illuminati in 1785.

15. Did the Illuminati Have a Hand in World Wars?

One of the most enduring conspiracy theories about the Illuminati is its alleged role in orchestrating major world events, particularly the World Wars. Some theories suggest that the Illuminati manipulated the political landscape to bring about wars that would further their agenda of global control. The theory posits that key figures, whether politicians or bankers, were covert members of the Illuminati, working behind the scenes to direct the course of history.

However, historians generally dismiss these claims due to the lack of substantial evidence. While it is true that many influential individuals have been associated with secret societies, there is no concrete proof that the Illuminati played a central role in either World War. These theories are often based on speculation, with little verifiable evidence to support the notion of an Illuminati-controlled global conspiracy.

16. How Did the Illuminati Use the Media?

The role of the media in the Illuminati’s alleged global agenda is another subject of fascination. Some conspiracy theorists argue that the Illuminati has long used the media to manipulate public opinion and shape global events. According to these theories, powerful figures who are members of the Illuminati control major media outlets, using them to propagate their ideas and further their influence.

While it is true that media manipulation has been a tool for political influence throughout history, there is no direct evidence linking the Illuminati to global media networks. The idea that the Illuminati controls the media is often cited in the context of modern conspiracy theories, but most historians believe that the influence of the Illuminati in media is more a product of speculation than fact.

17. How Did the Illuminati Impact the French Revolution?

The French Revolution is often cited as a key moment when the Illuminati’s influence supposedly shaped the course of history. Some believe that the Illuminati played a direct role in the revolution, either by inciting it or by providing ideological support to revolutionary figures. The Enlightenment ideals that the Illuminati espoused, such as liberty, equality, and fraternity, seemed to align with the revolutionary goals of overthrowing the monarchy and establishing a republic.

However, historians are divided on the extent of the Illuminati’s involvement in the revolution. While some key figures in the revolution may have been influenced by Enlightenment ideas, there is little evidence to suggest that the Illuminati orchestrated the events. The revolution was a complex social and political movement driven by a variety of factors, and while the Illuminati’s philosophy may have had some influence, it was likely only one among many contributing forces.

18. Why Did the Illuminati Attract Such Suspicion?

From its inception, the Illuminati was met with suspicion. This was due in part to its secretive nature, its rejection of religious authority, and its radical ideas about reforming society. The Illuminati’s clandestine operations, which included recruiting members from Freemasonry and other secret societies, fueled rumors and conspiracy theories about its true agenda.

The Illuminati’s strong opposition to religious institutions, particularly the Catholic Church, also made it a target of suspicion. Throughout history, secret societies have often been viewed with mistrust, especially when they challenge established power structures. In the case of the Illuminati, its perceived threat to both religious and political institutions led to widespread fear and ultimately contributed to its suppression by the Bavarian government in the 1780s.

19. Was the Illuminati a Single, Unified Organization?

Another mystery surrounding the Illuminati is whether it was ever truly a single, unified organization. While it started as a small group with specific goals, the Illuminati quickly expanded and absorbed members from various different backgrounds. As the group grew, its internal structure became more complex, with different factions and ideological divisions emerging.

Some historians argue that the Illuminati was never as unified as its enemies feared. The group’s internal dynamics were often marked by power struggles, disagreements, and personal rivalries. The idea of a single, monolithic Illuminati working toward a singular goal is likely a myth created by those who sought to demonize the order. In reality, the Illuminati may have been a loosely connected network of individuals with shared ideals, but with differing approaches to achieving their objectives.

20. Did the Illuminati Have a Secret Agenda for World Domination?

One of the most persistent conspiracy theories about the Illuminati is the claim that the order’s ultimate goal was world domination. According to this theory, the Illuminati was not merely a group advocating for Enlightenment reforms, but rather a secret cabal working to subvert governments and establish a New World Order, controlled by the elites.

While these theories have been widely circulated, there is no solid evidence to support the notion that the Illuminati sought global control. Most historians argue that the Illuminati’s goals were more focused on promoting rationalism, secularism, and Enlightenment values, rather than seeking domination. The idea of a “New World Order” orchestrated by the Illuminati is more a product of modern conspiracy theories than a reflection of the group’s actual activities in the 18th century.

Latest Updates

Let’s imagine, explore, and uncover the mysteries together!

Let’s imagine, explore, and uncover the mysteries together!