Introduction to Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is an artificial 82-kilometer (51-mile) waterway located in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It provides a shortcut across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama as it forms part of a conduit for maritime trade between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Locks at each end raise ships up to Gatun Lake, an artificial freshwater lake 26 meters (85 ft) above sea level, created by damming the Chagres River and Lake Alajuela to reduce the amount of excavation work required for the canal. Locks then lower the ships at the other end. Average of 200 ML/52,000,000 US gal fresh water is used in the passage of a ship. Low water levels during droughts are a threat to the canal.

The Panama Canal shortcut saves a huge amount of time for ships to travel between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, avoiding the long and dangerous route around the southernmost tip of South America via the Drake Passage, the Strait of Magellan, or the Beagle Channel. Its construction was one of the largest and most difficult engineering projects ever undertaken.

It has served since its opening on 15 August 1914 by successfully shortening maritime communication both in time and distance to invigorate maritime and economic transportation by offering a short and relatively inexpensive route of transit between the two oceans. It has been decisively influential on global trade patterns, boosting the growth of the economy both in developed and developing countries, and providing the general impetus for economic expansion in many out-of-the-way regions of the world.

Colombia, France, and later the United States held control over the territory surrounding the canal during construction. France first started work on the canal in 1881 but stopped this work in 1889 for lack of confidence among investors, engineering challenges, and a very high worker mortality rate.

The United States took over the project in 1904 and opened the canal in 1914. The US continued to control the canal and the surrounding Panama Canal Zone until the Torrijos–Carter Treaties in 1977, which provided for its handover to Panama. The government of Panama gained total control over it in 1999, following a period of joint American-Panamanian control. It is managed and operated by the Panama Canal Authority, a government-owned entity of Panama.

The original locks are 33.5 meters (110 ft) wide and permit Panamax-sized ships to pass. A third, wider lane of locks was built between September 2007 and May 2016. The expanded waterway started commercial operation on June 26, 2016. The new locks enable Neopanamax-sized ships to transit the canal.

Annual traffic has risen from about 1,000 ships in 1914, when the canal initially opened to navigation, to 14,702 vessels in 2008, amounting to 333.7 million Panama Canal/Universal Measurement System (PC/UMS) tons. Over 815,000 vessels had transited the canal up to 2012.

That year, the top five users of the canal were the United States, China, Chile, Japan, and South Korea. In 2017, it took ships an average of 11.38 hours to travel between the canal’s two outer locks. The American Society of Civil Engineers even ranked the Panama Canal one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World.

History

Early proposals in Panama

The idea of the Panama Canal is dated back in 1513 when the Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa first crossed the Isthmus of Panama. European powers rapidly recognized the possibility of a water passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans across this narrow land bridge connecting North and South America.

Plans from as early as 1534 were proposed about such a channel, with an order from the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V asking a survey for crossing the Americas toward smoothing sea travel between Spain and Peru. There’s explicit mention of proposals by the physician and philosopher Thomas Browne regarding the Isthmus of Panama as the only convenient location back in 1668.

The first attempt to make the isthmus part of a trade route was the infamous Darien scheme, launched by the Kingdom of Scotland in 1698-1700. It was, however, abandoned because conditions were too harsh in the region.

In 1811, the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt published an essay on the geography of the Spanish colonies in Central America (Essai politique sur le royaume de la Nouvelle Espagne; translated into English as Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain, containing research on the geography of Mexico).

In the essay, he discussed five alternative channels to possibly build a canal across Central America, among them Panama, but concluded that the most promising location was across Nicaragua, crossing Lake Nicaragua. His suggestions persuaded the British to try building a Nicaragua canal in 1843.

It was an effort doomed to failure, and this attempt culminated in the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty of 1850 between the United Kingdom and the United States, through which the two powers agreed to share control of any canal constructed in Nicaragua, or by extension anywhere in Central America.

In 1846, the US had negotiated a Mallarino-Bidlack Treaty with New Granada, the predecessor of Colombia, where both countries allowed the United States the right of passage and the authority to intervene militarily in the isthmus. In 1848, discovery of gold in California created demand for a fast passage between the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans.

This demand was exploited by American businessman William Henry Aspinwall, who ran steamship services from New York City to Panama, and from Panama to California, with an overland portage through Panama. Other businessmen, such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, soon followed suit.

Between 1850 and 1855, a syndicate founded by Aspinwall built a railroad (now the Panama Canal Railway) from Colón on the Caribbean Sea to Panama City. The project cost US$ 8,000,000-six times the estimated cost-and between 6,000 and 12,000 construction workers lost their lives to tropical diseases. Yet it rapidly became fantastically profitable for its owners.

In 1870, U.S. President Grant established an Interoceanic Canal Commission that assigned several naval officers, including Commander Thomas Oliver Selfridge Jr., to examine the possible routes suggested by Humboldt for a canal across Central America. The commission eventually made a decision in favor of Nicaragua, making it the preferred route among American policy-makers.

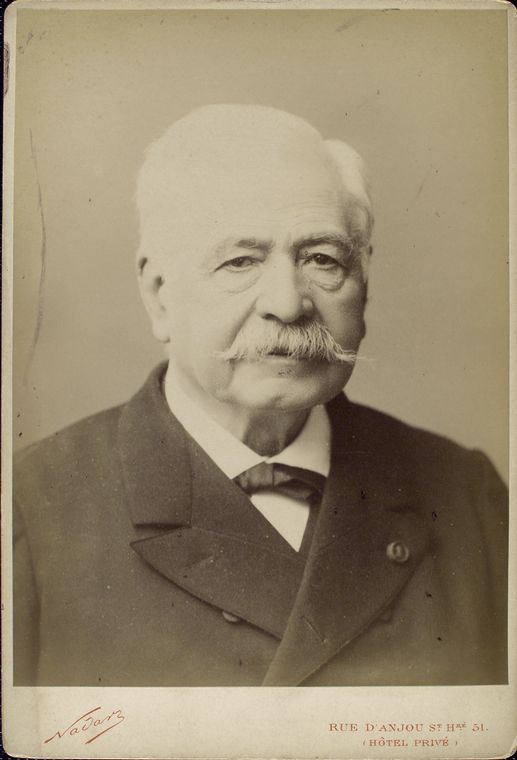

French construction attempts, 1881–1899

The French diplomat and entrepreneur Ferdinand de Lesseps was the driving force behind French attempts to construct the Panama Canal (1881-1889). De Lesseps had gained fame by successfully constructing the Suez Canal (1859-1869), a route that quickly proved its value in international commerce.

After this success, he actively sought new projects. In 1875, de Lesseps was approached by the Société Civile Internationale du Canal Interocéanique de Darien, also known as the “Türr Syndicate,” a group formed to promote the building of an interoceanic canal across Panama.

Among its directors were Hungarian freedom fighter István Türr, financier Jacques de Reinach, and Lt. Lucien Bonaparte-Wyse, brother-in-law of the former dictator. Between 1876 and 1878, Bonaparte-Wyse and Armand Reclus studied several possible routes across the Isthmus of Panama.

Bonaparte-Wyse traveled on horseback to Bogotá, where he obtained a concession from the Colombian government to build a canal across Panama on March 20, 1878. The agreement, known as the “Wyse Concession,” was valid for 99 years and granted the company the rights to dig and operate the canal.

In May 1879, de Lesseps called an international congress in Paris to discuss the feasibility of a ship canal across Central America. Of the 136 delegates from 26 countries, only 42 were engineers, while the rest were speculators, politicians, and friends of de Lesseps. De Lesseps used the congress to promote fundraising for his preferred plan, which was to build a sea-level canal across Panama, similar to the Suez Canal.

Despite some reservations from delegates who favored a canal in Nicaragua or who pointed out the potential engineering challenges and health risks, de Lesseps was able to gain approval from the majority for his plan. In the aftermath of the congress, he formed a company to build the canal, the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique de Panama. The company took over the Wyse Concession from the Türr Syndicate and was able to raise vast sums of money from petty French investors, on the enormous profits generated by the Suez Canal.

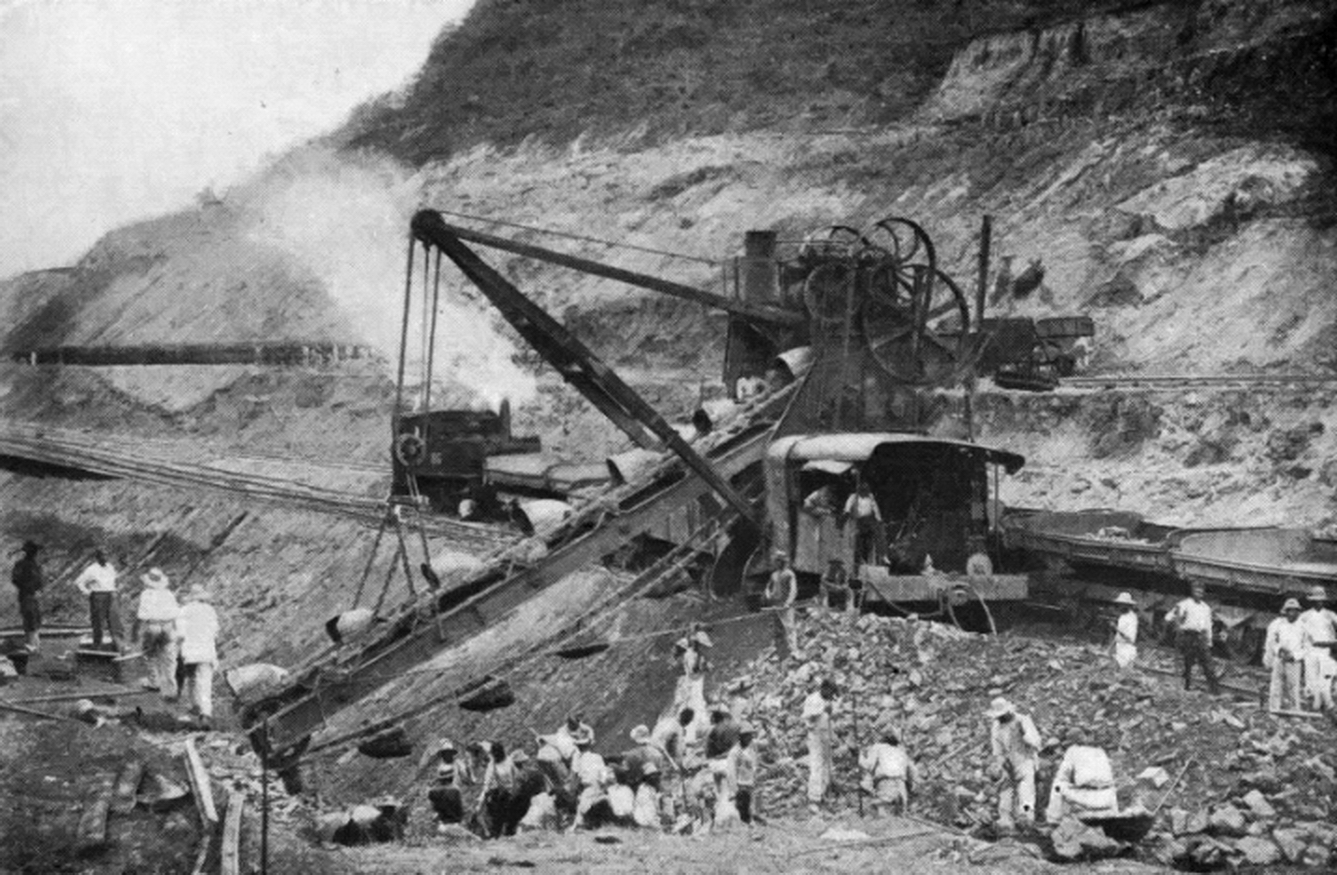

Construction started on 1 January 1881, with digging at Culebra on 22 January. A huge labor force was recruited and, by 1888, this had grown to around 40,000 workers; nine-tenths of these were Afro-Caribbean workers from the West Indies.

Although French skilled and high-paid engineers were attracted to the project, they were not easy to retain, as well as to keep them indoors due to the conditions and spread of diseases. The death toll was estimated at over 22,000 between 1881 and 1889, with as many as 5,000 of the victims being French citizens.

From the start, the French canal project suffered from difficulties. Even though the Panama Canal had to be only 40 percent as long as the Suez Canal, it was a much greater engineering problem due to the fact that it had tropical rain forests, debilitating climate, a need for canal locks, and that there was no ancient route to follow.

A string of main engineers lost hope and resigned beginning with Armand Reclus in 1882. Workers were not ready for the rainy season, during which the Chagres River, where the canal began, was a raging torrent up to 10 m (33 ft). From time to time, Culebra workers had to expand the main cut in the mountain and lower the angles of the slopes so that less landslide debris fell into the canal.

The dense jungle teemed with poisonous snakes, stinging insects, and biting spiders, but the ultimate enemies were yellow fever, malaria, and other insect-borne diseases that killed thousands of workers; by 1884, the death rate approached 200 workers per month.

Public health measures were ineffective because the role of mosquito, then a disease vector, was unheard of. The conditions of France were downplayed to prevent recruitment problems, but the high mortality rate kept an experienced workforce from persisting.

He maintained the flow of investment and labour in France far beyond the time when it had become clear that the goals could not be met, but then the money gave out. The French venture became bankrupt in 1889 at a reported US$287,000,000 ($9.73 billion in 2023) cost; around 22,000 men succumbed to diseases and accidents and the savings of 800,000 investors were lost.

Work was stopped on May 15 and the subsequent scandal, the Panama affair, saw several people involved accused of corruption; one of the main defendants, Gustave Eiffel, was indeed taken to court. De Lesseps and his son Charles were found guilty of embezzlement and condemned to five years’ imprisonment; however, that decision was cancelled later on, and the father never was imprisoned while still being alive, aged 88.

In 1894, another French company, Compagnie Nouvelle du Canal de Panama, was established, thus taking the project over. A negligible number of a few thousand workers were engaged, mainly to satisfy the terms of the Colombian concession granting the Panama Canal and to keep the Panama Railroad running while maintaining the existing excavation and equipment in salable condition.

The company sought a buyer for these assets, with an asking price of US$109,000,000 ($3.84 billion in 2023). Meanwhile, they continued with enough activity to maintain their franchise. Two lobbyists would become particularly active in later negotiations to sell the interests of the Compagnie Nouvelle.

The American lawyer William Nelson Cromwell began looking after the interests of the company in 1894, after first acting for the related Panama Railroad. He would become deeply involved as a lobbyist in the American decisions to continue the canal in Panama, and to support Panamanian independence. Philippe Bunau-Varilla, a leader of the greatest subcontractors on the first contract to the company, had also been forced, by the receivers, to purchase shares in the Compagnie Nouvelle. After this, he was appointed chief of engineers in the Compagnie Nouvelle.

American purchase

At this time, US President Theodore Roosevelt and the United States Senate were interested in establishing a canal across the isthmus, with some favoring a canal across Nicaragua and others advocating the purchase of the French interests in Panama. Bunau-Varilla, who was seeking American involvement, asked for $100 million, but accepted $40 million in the face of the Nicaraguan option. In June 1902, the US Senate voted in favor of the Spooner Act to pursue the Panamanian option, provided the necessary rights could be obtained.

On 22 January 1903, the Hay–Herrán Treaty was signed by United States Secretary of State John M. Hay and Colombian Chargé Tomás Herrán. For $10 million and an annual payment, it would have granted the United States a renewable lease in perpetuity from Colombia on the land proposed for the canal. The treaty was ratified by the US Senate on 14 March 1903, but the Senate of Colombia unanimously rejected the treaty since it had become highly unpopular in Bogotá because of the fear of insufficient compensation, threat to sovereignty, and perpetuity.

Roosevelt shifted his policy, partly based on the Mallarino–Bidlack Treaty of 1846, and he actively supported the separation of Panama from Colombia. Just a few weeks after Panama declared its independence, he signed a treaty with the new Panamanian government under terms that were very close to the Hay–Herrán Treaty.

On 2 November 1903, US warships blocked sea lanes against possible Colombian troop movements en route to put down the Panama rebellion. Panama declared independence on 3 November 1903. The United States quickly recognized the new nation. This happened so quickly that by the time the Colombian government in Bogotá launched a response to the Panamanian uprising, US troops had already entered the rebelling province.

Colombian troops dispatched to Panama consisted of hastily assembled conscripts, who had no proper training. Although these conscripts could easily defeat the Panamanian rebels, they could not defeat US army troops, which were helping the Panamanian rebels.

An army of conscripts was the best the Colombians could respond with as Colombia was coming out of a civil war between Liberals and Conservatives from October 1899 to November 1902, commonly referred to as the ‘Thousand Days War.

‘ The US was fully aware of these conditions and even included them in the planning of the Panama intervention as the US played the role of an arbitrator between the two sides. The peace treaty that ended the ‘Thousand Days War’ was signed on 21 November 1902 on the USS Wisconsin.

During their visit to the port, the US brought their engineering teams with the peace delegation to start planning the construction of the canal before the US had even gained the rights to build the canal. All these factors would bring about an inability on the part of the Colombians to crush the rebellion in Panama and oust the United States troops who then occupied what is today the independent nation of Panama.

On 6 November 1903, Philippe Bunau-Varilla, as Panama’s ambassador to the United States, signed the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty granting rights to the United States to build and administer the Panama Canal Zone and its defenses.

This treaty gave the US some rights to the canal ‘in perpetuity,’ but in article 22 limited other rights to a lease period of 99 years. The treaty was shortly afterwards condemned by many Panamanians as an infringement upon their country’s new national sovereignty. This was to become a contested diplomatic issue involving Colombia, Panama, and the United States.

President Roosevelt famously said, ‘I took the Isthmus, started the canal and then left Congress not to debate the canal, but to debate me.’ Several parties in the United States labeled this as an act of war against Colombia: The New York Times wrote that the aid provided by the United States to Bunau-Varilla was ‘an act of sordid conquest.’

The New York Evening Post termed it a ‘vulgar and mercenary venture.’ US maneuvers are usually cited as the classic example of US gunboat diplomacy in Latin America, and the best example of what Roosevelt said by the old African adage, ‘Speak softly and carry a big stick [and] you will go far.’ After the revolution in 1903, the Republic of Panama remained a US protectorate till 1939.

In 1904, the United States purchased the French equipment and excavations, including the Panama Railroad for US$40 million, with $30 million relating to excavations completed, principally in the Culebra Cut, which are estimated to cost about $1.00 per cubic yard. The United States also paid to the new state of Panama $10 million and each subsequent year made a payment of $250,000.

In 1921, Colombia and the United States signed the Thomson–Urrutia Treaty, in which the United States agreed to pay Colombia $25 million: $5 million upon ratification, and four $5 million annual payments, and grant Colombia special privileges in the Canal Zone. In return, Colombia recognized Panama as an independent nation.

21st century

Donald Trump’s assertions

On 21 December 2024, US President-elect Donald Trump stated that the United States should take control of the Panama Canal from Panama, saying that the rates Panama was charging American ships were ‘exorbitant’ and a violation of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties. The next day, he stated that the canal was ‘falling into the wrong hands,’ referring to China. Soon after, the Panamanian president, José Raúl Mulino, responded, denying that the United States was being unfairly charged or that anyone aside from Panama had control of the canal, and affirming that the canal was part of the country’s ‘inalienable patrimony.’

On 24 December, protesters demonstrated at the U.S. Embassy in Panama City over Trump’s threat to take back the Panama Canal. The demonstrators called him a ‘public enemy’ of Panama. On the same day, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA), ten Central and South American countries, condemned Trump’s remarks and confirmed its commitment to supporting Panama’s ‘sovereignty, territorial integrity and self-determination.’

On 7 January 2025, in a press conference, Trump vowed to take control of the Panama Canal. He refused to rule out economic and military action against Panama to seize control of the canal to secure what he called U.S. ‘economic security.’ He reiterated the same intent as stated in his inaugural address on 20 January.

Canal

Layout

While globally the Atlantic Ocean is east of the isthmus and the Pacific is west, the general direction of the canal passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific is from northwest to southeast, because of the shape of the isthmus at the point the canal occupies. The Bridge of the Americas (Spanish: Puente de las Américas) on the Pacific side is a third of a degree east of the Colón end on the Atlantic side. Still, in formal nautical communications, the simplified directions ‘southbound’ and ‘northbound’ are used.

The canal consists of artificial lakes, several improved and artificial channels, and three sets of locks. An additional artificial lake, Alajuela Lake (known during the American era as Madden Lake), acts as a reservoir for the canal. The layout of the canal as seen by a ship passing from the Atlantic to the Pacific is:

- From the formal marking line of the Atlantic Entrance, one enters Limón Bay (Bahía Limón), a large natural harbor. The entrance runs 8.9 km (5+1⁄2 mi). It provides a deepwater port (Cristóbal), with facilities like multimodal cargo exchange (to and from train) and the Colón Free Trade Zone (a free port).

- A 3.2 km (2 mi) channel forms the approach to the locks from the Atlantic side.

- The Gatun Locks, a three-stage flight of locks 2.0 km (1+1⁄4 mi) long, lifts ships to the Gatun Lake level, some 27 m (87 ft) above sea level.

- Gatun Lake, an artificial lake formed by the building of the Gatun Dam, carries vessels 24 km (15 mi) across the isthmus. It is the summit canal stretch, fed by the Gatun River and emptied by basic lock operations.

- From the lake, the Chagres River, a natural waterway enhanced by the damming of Gatun Lake, runs about 8.4 km (5+1⁄4 mi). Here the upper Chagres River feeds the high-level-canal stretch.

- The Culebra Cut slices 12.5 km (7+3⁄4 mi) through the mountain ridge, crosses the continental divide and passes under the Centennial Bridge.

- The single-stage Pedro Miguel Lock, which is 1.4 km (7⁄8 mi) long, is the first part of the descent with a lift of 9.4 m (31 ft).

- The artificial Miraflores Lake 1.8 km (1+1⁄8 mi) long, and 16 m (54 ft) above sea level.

- The two-stage Miraflores Locks is 1.8 km (1+1⁄8 mi) long, with a total descent of 16 m (54 ft) at mid-tide.

- From the Miraflores Locks one reaches Balboa harbor, again with multimodal exchange provision (here the railway meets the shipping route again). Nearby is Panama City.

- From this harbor an entrance/exit channel leads to the Pacific Ocean (Gulf of Panama), 13.3 km (8+1⁄4 mi) from the Miraflores Locks, passing under the Bridge of the Americas.

Legend

Thus, the total length of the canal is 80 km (50 mi). In 2017 it took ships an average of 11.38 hours to pass between the canal’s two outer locks.

Deep Research on Panama Canal

A Deep Dive into the Panama Canal: A Marvel of Engineering and Global Trade

The Panama Canal, a monumental feat of engineering, stands as a testament to human ingenuity and its profound impact on global trade. This artificial 82-kilometer (50 mi) waterway connects the Atlantic Ocean (via the Caribbean Sea) to the Pacific Ocean, effectively bypassing the lengthy and perilous journey around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America. Its creation dramatically reduced shipping times and costs, revolutionizing international commerce and shaping the geopolitical landscape. This exploration delves into the canal’s history, construction, operation, and enduring significance.

A History Forged in Ambition and Adversity

The concept of a trans-isthmian canal dates back to the early 16th century when Spanish explorers recognized the strategic advantage of such a waterway. However, it wasn’t until the late 19th century that serious efforts began. A French company, led by Ferdinand de Lesseps, the builder of the Suez Canal, initiated construction in 1881. Plagued by engineering challenges, tropical diseases (particularly malaria and yellow fever), and financial difficulties, the French project ultimately failed.

American Ingenuity and Triumph

In the early 20th century, the United States, under President Theodore Roosevelt, recognized the canal’s strategic and economic importance and purchased the French assets. The US embarked on a renewed construction effort, overcoming the previous obstacles through significant advancements in engineering and sanitation. Notably, the work of Dr. William C. Gorgas in controlling mosquito populations drastically reduced the incidence of disease, allowing the project to proceed. The canal officially opened on August 15, 1914, coinciding with the outbreak of World War I.

The Lock System: A Masterpiece of Engineering

The Panama Canal utilizes a lock system to raise ships from sea level to the level of Gatun Lake, an artificial lake created as part of the canal, and then lower them back down to sea level on the other side. Each lock chamber is a massive concrete structure with enormous gates that control the flow of water. The locks operate by gravity, with water flowing between chambers to raise or lower the ships. This ingenious system allows vessels to traverse the mountainous terrain of the Isthmus of Panama.

Operation and Maintenance: A Continuous Endeavor

The Panama Canal Authority (ACP), an autonomous agency of the Panamanian government, manages and operates the canal. The ACP is responsible for maintaining the locks, dredging the canal channel, and providing services to transiting vessels. The canal operates 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, with a complex system of scheduling and traffic control to ensure efficient and safe passage. Ongoing maintenance and modernization efforts are crucial to keep the canal operating at peak capacity.

Expansion and Modernization: Adapting to Changing Times

In response to the increasing size of container ships, a major expansion project, known as the Third Set of Locks Project, was completed in 2016. This expansion created a new lane of traffic and doubled the canal’s capacity, allowing larger “Neopanamax” vessels to transit. The expansion ensured the canal’s continued relevance in the face of evolving global shipping trends.

Economic and Geopolitical Significance: A Global Hub

The Panama Canal plays a vital role in global trade, connecting major economies and facilitating the movement of goods between the Atlantic and Pacific basins. It significantly reduces shipping times and costs for numerous industries, including container shipping, bulk cargo, and cruise tourism. The canal’s strategic location also makes it a key geopolitical asset, influencing global power dynamics and trade routes.

Despite its success, the Panama Canal faces ongoing challenges. These include maintaining water levels during dry seasons, managing sedimentation, and adapting to further increases in ship size. Climate change and its potential impacts on rainfall patterns also pose a significant concern. The ACP continues to invest in research and development to address these challenges and ensure the canal’s long-term sustainability and competitiveness.

A Legacy of Innovation and Global Connection

The Panama Canal stands as a remarkable achievement of human endeavor, a symbol of international cooperation, and a vital artery of global trade. Its impact on the world economy and geopolitical landscape is undeniable. As the world continues to evolve, the Panama Canal will undoubtedly play a crucial role in shaping the future of global commerce and connectivity.