The Alhambra (/ælˈhæmbrə/, Spanish: [aˈlambɾa]; Arabic: الْحَمْرَاء, romanized: al-ḥamrāʼ ) is the palace and fortress complex on the east bank of a small ria on a plateau above the town of Granada, Spain. It is one of the most famous monuments of Islamic architecture and one of the best-preserved palaces of the historic Islamic world, additionally containing notable examples of Spanish Renaissance architecture.

| Location | Granada, Spain |

|---|---|

| Website | Patronato de la Alhambra |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, iv |

| Designated | 1984 (8th session) |

| Part of | Alhambra, Generalife and Albayzín, Granada |

| Reference no. | 314-001 |

| Region | List of World Heritage Sites in Southern Europe |

| Type | Non-movable |

| Criteria | Monument |

| Designated | 10 February 1870 |

| Reference no. | RI-51-0000009 |

The complex was initiated in 1238 by Muhammad I Ibn al-Ahmar, the first Nasrid emir and founder of the Emirate of Granada, the last Muslim state of Al-Andalus. It was constructed on the Sabika hill, an outcrop of the Sierra Nevada which had been the site of earlier fortresses and of the 11th-century palace of Samuel ibn Naghrillah. Later Nasrid rulers continuously modified the site.

The major construction campaigns which defined the character of most of the royal palaces were in the 14th century during the reigns of Yusuf I and Muhammad V. The site subsequently became the Royal Court of Ferdinand and Isabella during which Christopher Columbus received royal endorsement for his expedition after the conclusion of the Christian Reconquista in 1492; the palaces were partially modified.

In 1526, Charles V commissioned a new Renaissance-style palace in direct juxtaposition with the Nasrid palaces, but it was left uncompleted in the early 17th century. The site fell into disrepair over the following centuries, with its buildings occupied by squatters. The troops of Napoleon destroyed parts of it in 1812.

After this, the Alhambra became an attraction for British, American, and other European Romantic travellers. The most influential of them was Washington Irving, whose Tales of the Alhambra (1832) brought international attention to the site.

The Alhambra was one of the first Islamic monuments to become the object of modern scientific study and has been the subject of numerous restorations since the 19th century. It is now one of Spain’s major tourist attractions and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

During the Nasrid era, Alhambra was an independent city apart from the rest of Granada. It had nearly all of the features found in a Muslim city including a Friday mosque, public baths called hammams, roads, houses, artisanal workshops, a tannery, and an excellent water supply system.

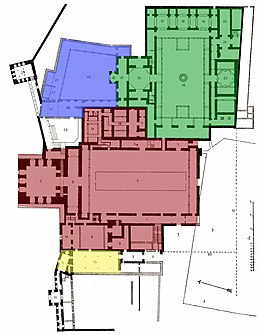

The place was an important royal city and citadel, holding at least six major palaces on its grounds; most were located along the northern side, which presented excellent viewscapes overlooking the Albaicín quarter. Mexuar, the Comares Palace, the Palace of the Lions, and Partal Palace, which all are the principal tourist sights today, remain the most famous and preserved palaces.

Other palaces were known only by documents from different historical periods, as well as modern excavations in recent times. To the west, there stands the Alcazaba fortress. Smaller towers and fortified gates are found throughout the walls. On the eastern side, beyond the Alhambra walls, is the Generalife. This is an old Nasrid country estate and a summer palace with historic orchards and modern landscaped gardens.

The Nasrid palaces embody the Moorish architectural tradition developed over several centuries. It is represented by the use of a courtyard as a central space and as an organizing element, along which other halls and rooms were arranged. These usually featured water elements at the center of the courtyards, such as a reflective pool or a fountain.

Interior decoration was promoted, with lower walls featuring tile mosaics and the upper walls decorated with intricate stucco carvings. The main decorative themes were geometric patterns, vegetal designs, and Arabic inscriptions. In addition to this, “stalactite”-like sculpting, which is known as muqarnas, was also used for three-dimensional features such as vaulted ceilings to give the architectural richness.

Etymology

The name “Alhambra” is derived from the Arabic word الْحَمْرَاء (al-Ḥamrāʼ), meaning “the red one” (feminine). Its full Arabic form is الْقَلْعَةُ ٱلْحَمْرَاءُ (al-Qalʻat al-Ḥamrāʼ), which translates to “the red fortress.” The prefix “Al-” in “Alhambra” means “the” in Arabic, but in both English and Spanish, the name is often used with an additional definite article. The name’s reference to the color red is a derivation of its reddish walls due to the construction with rammed earth. The colour reddish tint comes through due to iron oxide being found in local clay applied to the structure.

Most of the names in use for specific structures and locations in the Alhambra are imaginative titles coined after the medieval period, frequently during the 19th century. The original Arabic names of the Nasrid-era buildings are not known, but some researchers believe that certain structures and historical names have associations.

History

Origins and early history

The existence of a Roman presence on the Sabika hill is not evident, but archaeologists have found remains of ancient foundations in the area. A fortress or citadel, probably from the Visigothic period, was present on the hill by the 9th century. The first known mention of the Qal’at al-Ḥamra occurred during the battles between the Arabs and the Muladies under the rule of ‘Abdallah ibn Muhammad (r. 888–912).

Historically, texts written at this time mention that the red castle was of average size and not strong enough walls to be able to fend off a determined army. The earliest known mention of al-Ḥamrāʼ is ascribed to a line of verse accompanying an arrow shot over the ramparts, which was recorded by Ibn Hayyan (d. 1076).

“Deserted and roofless are the houses of our enemies;

Invaded by the autumnal rains, traversed by impetuous winds;

Let them within the red castle (Kalat al hamra) hold their mischievous councils;

Perdition and woe surround them on every side.”

The region of Granada was initially ruled by the Zirids, a Sanhaja Berber group, and a branch of the Zirids who ruled parts of North Africa in the early 11th century. After the downfall of the Caliphate of Córdoba in 1009 and Fitna (civil war), Zirid leader Zawi ben Ziri declared an independent kingdom called Taifa of Granada. The Zirids built their citadel and palace, known as the al-Qaṣaba al-Qadīma or “”Old Citadel” or “”Old Palace”, atop what is now the hill which forms the Albaicín neighborhood. These also connected two other fortresses on the Sabika hill and the Mauror hills to the south.

Between the Zirid citadel and the Sabika hill on the Darro River was a sluice gate known as Bāb al-Difāf (\”Gate of the Tambourines\”), which could be closed to retain water when necessary. This gate formed part of the fortifications linking the Zirid citadel to the fortress on the Sabika hill and was also part of a coracha (from the Arabic qawraja), a fortified structure enabling soldiers to access the river and bring water back even during a siege. The Sabika hill fortress, also known as al-Qasaba al-Jadida (“the New Citadel”), later formed the foundations of the present-day Alcazaba of the Alhambra.

Under the Zirid kings Habbus ibn Maksan and Badis, the most influential figure in the kingdom was the Jewish administrator Samuel ha-Nagid (in Hebrew) or Isma’il ibn Nagrilla (in Arabic). Samuel built his own palace on the Sabika hill, possibly on the site of the current palaces, though no remains of it exist today. It reportedly featured gardens and water installations.

Nasrid period

The Taifa kingdoms’ period ended with the invasion of al-Andalus by the Almoravids from North Africa in the late 11th century. They were followed by the Almohads in the mid-12th century. From 1228 onwards, Almohad rule crumbled and local rulers and factions arose in all parts of the territories of al-Andalus.

At the same time, the Reconquista was in full swing. The Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragon gained immense ground under Ferdinand III and James I respectively. The conquests included that of Córdoba by Castile in 1236 and Seville by the same in 1248.

Meanwhile, Ibn al-Ahmar, otherwise known as Muhammad I, laid the foundation for what eventually turned out to be the last and longest Muslim-ruled dynasty in the Iberian Peninsula – the Nasrids in the Emirate of Granada. Ibn al-Ahmar was a relatively new political figure in the region who, likely of humble birth, succeeded in gaining the allegiance of various Muslim communities in face of the advancing Castilian forces.

Upon settling in Granada in 1238, Ibn al-Ahmar at first moved to the old Zirid citadel on Albaicín hill. In that same year, however, he started building the Alhambra as a new dwelling and stronghold. According to an Arabic manuscript, now published under the title of Anónimo de Madrid y Copenhague,

This year, 1238 Abdallah ibn al-Ahmar ascended to the place called “the Alhambra”. He viewed it, established the bases of a fortress and entrusted someone in charge of conducting the task and before the end of this year had elapsed, work on the ramparts had been completed; water from the river was drawn, and a channel containing water was constructed (.)

During the Nasrid Dynasty, the Alhambra was transformed into a palatine city. It featured an advanced irrigation system made up of aqueducts and water channels that supplied water to the complex and nearby countryside palaces such as the Generalife. The old fortresses on the hill had previously relied on rainwater collected from a cistern near the Alcazaba and water brought up from the Darro River below.

The creation of the Saqiyat al-Sultan, or the canal that brought water from the mountains to the east side, cemented the idea of the Alhambra as a palace city rather than a defensive, ascetic structure. Initial hydraulic systems were later further developed into two long, winding water channels and other advanced elevation devices designed for bringing water to the plateau.

The only elements preserved from the time of Ibn al-Ahmar are some of the fortification walls, particularly the Alcazaba at the western end of the complex. Ibn al-Ahmar did not find the time to finish any new major palaces and presumably used one of the Alcazaba towers at least initially before later transferring residence to a modest house on the site on which the Palace of Charles V would stand today. Successive Nasrid rulers continued the evolution of the site into his time. This makes the exact chronology of the Alhambra’s development difficult to determine, as it was constructed with delicate materials that needed frequent repairs.

The oldest major palace for which some remains have been preserved is the Palacio del Partal Alto, located in an elevated position near the center of the complex. This structure probably dates from the reign of Ibn al-Ahmar’s son, Muhammad II (r. 1273–1302). South was the Palace of the Abencerrajes, and eastward, another private palace called the Palace of the Convent of San Francisco, which were probably built in the time of Muhammad II as well.

Muhammad III (r. 1302–1309) built the Partal Palace, parts of which are still standing today, and he also constructed the Alhambra’s main mosque (which stood on the site of the current Church of Santa María de la Alhambra). The Partal Palace is the earliest known palace built along the northern walls of the Alhambra complex, offering views of the city below. It is also the oldest Nasrid palace still standing today.

Isma’il I (r. 1314–1325) carried out much remodeling of the Alhambra, initiating what is considered the “classical” period of Nasrid architecture. His rule marked the beginning of when major monuments in the Alhambra were initiated, and most decorative styles were consolidated.

Isma’il decided to construct a new palace complex just east of the Alcazaba to serve as the official residence of the sultan and the state, known as the Qaṣr al-Sultan or Dār al-Mulk. The core of this complex was the Comares Palace, with another wing, the Mexuar, extending to the west. The Comares Baths are the best-preserved feature from this early construction, though the rest of the palace was further modified by his successors.

Near the main mosque, Isma’il I also created the Rawda, the dynastic mausoleum of the Nasrids, of which only partial remains have survived. His successor, Yusuf I (r. 1333–1354), carried out further work on the Comares Palace, including the construction of the Hall of Ambassadors and additional modifications around the Mexuar. Yusuf also built the Alhambra’s main gate, the Puerta de la Justicia, and the Torre de la Cautiva, one of several small towers along the northern walls that feature richly decorated rooms.

Muhammad V’s reign (1354–1391, with interruptions) was the political and cultural apogee of the Nasrid emirate, as well as the apogee of Nasrid architecture. During his second reign (after 1362), there was a stylistic shift toward more innovative architectural layouts and the use of complex muqarnas vaulting.

His most important contribution to the Alhambra was the construction of the Palace of the Lions, built to the east of the Comares Palace in a space that had previously been occupied by gardens. He also remodeled the Mexuar, created the highly decorated “Comares Façade” in the Patio del Cuarto Dorado, and redecorated the Court of the Myrtles, giving these areas much of their final appearance.

With the exception of the Torre de las Infantas, which was built during the reign of Muhammad VII (1392–1408), the Alhambra saw relatively little major construction after Muhammad V. The Nasrid dynasty was in decline and turmoil during the 15th century, with few major construction projects and a more repetitive, less inventive architectural style.

Reconquista and Christian Spanish period

It is the last Nasrid Sultan, Muhammad XII of Granada, who surrendered Emirate of Granada in January 1492, when the troops of the Catholic Monarchs – King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile did not attack Alhambra itself but captured all the surrounding territory with its overwhelming military force. Before his surrender, Muhammad XII moved the remains of his ancestors from the Alhambra, a fact that was verified by Leopoldo Torres Balbás in 1925 when he discovered seventy empty tombs. The remains are currently believed to be in Mondújar in the principality of Lecrín.

After the conquest, the Alhambra became a royal palace and property of the Spanish Crown. Isabella and Ferdinand initially took up residence there and stayed in Granada for several months, until 25 May 1492. During this time, two major events occurred.

On 31 March, the monarchs signed the Alhambra Decree, which ordered the expulsion of all Jews in Spain who refused to convert to Christianity. In addition, Christopher Columbus, who had just been an eyewitness to the fall of Granada, also came to present his plan for a transatlantic voyage to the monarchs in the Hall of Ambassadors. On 17 April, they signed the contract which agreed on the terms for the expedition, which ultimately led to Columbus’s arrival in the Americas later that year.

Following the conquest, the new Christian rulers started to add and modify the Alhambra. The Tendilla family was entrusted with the governorship of the Alhambra and was given one of the Nasrid palaces, the Palacio del Partal Alto (near the Partal Palace), to use as their family residence. Iñigo López de Mendoza y Quiñones (d. 1515), the second Count of Tendilla, was among Ferdinand II’s retinue when Muhammad XII surrendered the keys to the Alhambra. He was the first Spanish governor of the Alhambra.

For nearly 24 years after the conquest, he made repairs and modifications to the fortifications of the Alhambra to make it more secure against gunpowder artillery attacks. In this period, many towers and fortifications, including the Torre de Siete Suelos, the Torre de las Cabezas, and the Torres Bermejas, were built or reinforced with semi-round bastions. In 1512, the Count was also granted the property of Mondéjar, and he left the title of Marquis of Mondéjar to his heirs.

In 1526, Charles V (r. 1516–1556) visited the Alhambra with his wife Isabella of Portugal and decided to convert it into a royal residence for his use. He repaired or remodelled parts of the Nasrid palaces into palaces used as royal chambers, something he did starting 1528 up to 1537. Part of the Comares Palace, he demolished as it ceded grounds for another monumental new palace, but this time made entirely with design suited to Renaissance style, by the same period, so he gave way for his Palace of Charles V. Construction of the palace started in 1527 but was eventually abandoned incomplete after 1637.

The Tendilla-Mondéjar family’s governorship ended in 1717–1718 when Philip V confiscated the properties of the family in Alhambra and dismissed the Marquis of Mondéjar, José de Mendoza Ibáñez de Segovia (1657–1734), as mayor of Alhambra from his post in revenge for Marquis’ opposing him during the War of the Spanish Succession.

The Tendilla-Mondéjar’s departure marks the beginning of the most severe period the Alhambra goes through regarding decline. On this period, the Spanish state devoted its fewest resources to it while its management was taken over by self-interested local governors who stayed with their family inside the neglected palaces.

The Alhambra was further damaged over subsequent years. Between 1810 and 1812 Napoleon’s army occupied Granada in the Peninsular War. The French troops, led by Count Sebastiani, occupied the Alhambra as a fortified position, causing heavy damage to the monument. They attempted to dynamite the whole complex to prevent its reuse as a fortified position while evacuating the city.

They managed to blow up eight towers before the remaining fuses were extinguished by Spanish soldier José Garcia, who saved what is left of today. In 1821, an earthquake further devastated it. During the early 19th century, it was described as being occupied by prisoners, disabled soldiers, and other marginalized people.

Recovery and modern restorations

As early as the second half of the 18th century, details and forms of the Alhambra started being documented by Spanish illustrators and officials. Other European writers started to focus attention on it by the first decade of the 19th century, and it subsequently became an object of fascination for Western Romanticist writers, whose publications often tried to evoke a contrast between the ornate architecture of the former Moorish palaces and their present state of ruin and neglect.

This also coincided with a growing European interest in the Orient, which encouraged an emphasis on exoticism and on the ‘oriental’ attributes of the Alhambra. This rediscovery of the Alhambra was led mostly by French, British, and German writers.

In 1830, the American writer Washington Irving lived in Granada and wrote his Tales of the Alhambra, first published in 1832, which would play a major role in stimulating international interest in southern Spain and in its Islamic-era monuments like the Alhambra. Other artists and intellectuals like John Frederick Lewis, Richard Ford, François-René de Chateaubriand, and Owen Jones, helped make the Alhambra an icon of the era with their writings and illustrations during the 19th century.

Restoration work on the Alhambra was undertaken in 1828 by the architect José Contreras, endowed in 1830 by Ferdinand VII. After the death of Contreras in 1847, it was continued by his son Rafael (died 1890) and his grandson Mariano Contreras (died 1912). The Contreras family members remained the most important architects and conservators of the Alhambra until 1907.

In this period, they largely adhered to a theory of ‘stylistic restoration,’ which promoted the building and addition of elements to make a monument ‘complete’ but not necessarily corresponding to any historical reality. They introduced elements which they considered to be characteristic of what they believed to be an ‘Arabic style,’ underlining the Alhambra’s supposed ‘Oriental’ nature.

For instance, in 1858–1859 Rafael Contreras and Juan Pugnaire introduced Persian-looking spherical domes to the Court of the Lions and to the northern portico of the Court of the Myrtles, although these had nothing to do with Nasrid architecture.

In 1868, a revolution overthrew Isabella II and the government took the properties of the Spanish monarchy, which included the Alhambra. In 1870 the Alhambra was declared a National Monument of Spain and the state provided a budget for its conservation under the Provincial Commission of Monuments. Mariano Contreras, the last of the Contreras architects to direct conservation at the Alhambra, became architectural curator in April 1890.

His stay was controversial and his new strategy of conservation attracted controversy from other authorities. In September 1890, a fire spread across a great part of the Sala de la Barca in the Comares Palace, thus pointing towards the vulnerability of the location. A report was published in 1903. This led to the establishment of a ‘Special Commission’ in 1905. The Special Commission was given the duty of taking care of conservation and restoration work at Alhambra.

The commission could not, however, exercise its control due to friction with Contreras. In 1907, Mariano Contreras was replaced by Modesto Cendoya, who too was not appreciated for his work. Cendoya started several digs in search of new treasures but often abandoned the work when it was half done. He managed to restore some significant elements, such as the water supply system, but abandoned the rest.

Due to continued friction with Cendoya, the Special Commission was dissolved in 1913 and the council (Patronato) of the Alhambra in 1914, which was tasked once again with managing the site’s conservation and Cendoya’s work. In 1915, it was attached directly to the Directorate-General of Fine Arts of the Ministry of Public Education (later the Ministry of National Education). As his predecessor Mariano Contreras, Cendoya continued to clash with the supervisory body and to obstruct their control. He was dismissed from his position in 1923.

After Cendoya, the chief architect from 1923 to 1936 was Leopoldo Torres Balbás, who was a trained archaeologist and art historian. Torres Balbás’s appointment marked a definite shift towards a more scientific and systematic approach to the conservation of the Alhambra. He supported the precepts of the 1931 Athens Charter for the Restoration of Monuments, which maintained regular maintenance, respect for the work of the past, legal protection for heritage monuments, and the legitimacy of modern techniques and materials in restoration so long as these were visually recognizable.

Many of the buildings in the Alhambra suffered at his hands. The Contreras architects made some wrong changes and additions that were reversed. The young architect ‘opened arcades that had been walled up, re-excavated filled-in pools, replaced missing tiles, completed inscriptions that lacked portions of their stuccoed lettering, and installed a ceiling in the still unfinished palace of Charles V.’

He carried out systematic archaeological excavations at many parts of the Alhambra and dug out lost Nasrid structures, including the Palacio del Partal Alto and the Palace of the Abencerrajes, with results that gave much better comprehension of the former palace-city as a whole.

The Alcazaba before and after 20th-century restoration work (view of the Torre Quebrada)

His assistant, Francisco Prieto Moreno, was responsible for the continuation of his work and served as the chief architectural curator from 1936 to 1970. In 1940, a new Council of the Alhambra was instated to oversee the place, which has been in charge to this day.

In 1984, the central government in Madrid transferred the responsibility for the site to the Regional Government of Andalusia and in 1986 new statutes and documents were developed to regulate the planning and protection of the site. In 1984, the Alhambra and Generalife were also listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Alhambra is now one of the most popular tourist destinations in Spain. Research, archaeological investigations, and restoration works have continued unabated into the 21st century.

Layout

The Alhambra complex is approximately 700 to 740 m (2,300 to 2,430 ft) in length and about 200 to 205 m (660 to 670 ft) at its greatest width. It runs from west-northwest to east-southeast and covers an area of approximately 142,000 m² (1,530,000 sq ft) or 35 acres. It stands on a narrow promontory overlooking the Vega or Plain of Granada and is carved by the river Darro on its north side as it descends from the Sierra Nevada. The red earth in which the fortress is erected is a granular aggregate supported by a medium of red clay, giving the emergent layered brick- and stone-reinforced construction its characteristic tone and at the root of ‘the Red Hill’.

The most westerly feature is the Alcazaba, a large fortress standing over the city. In order to meet touristic demand, modern access goes against the original sequence which started from a principal access via the Puerta de la Justicia (Gate of Justice) onto a large souq or public market square facing the Alcazaba, now subdivided and obscured by later Christian-era development.

From the Puerta del Vino ran the Calle Real or Royal Street, dividing Alhambra along its axial spine into a southern residential quarter, with mosques, hamams, or bathhouses, and many functional establishments, and an extended northern part, consisting of several palaces of nobility with large decorated gardens with views over the Albaicín.

The rest of the plateau consists of several Moorish palaces, both earlier and later, surrounded by a fortified wall and thirteen defensive towers, such as the Torre de la Infanta and Torre de la Cautiva, which contain miniature versions of elaborate vertical palaces. The river Darro passes through a ravine to the north and separates the plateau from the Albaicín district of Granada.

Similarly, the Sabika Valley, embracing the Alhambra Park, lies on the west and south, and, beyond this valley, the almost parallel ridge of Monte Mauror separates it from the Antequeruela district. Another ravine separates it from the Generalife, the summer pleasure gardens of the emir. Salmerón Escobar writes that the later planting of deciduous elms obscures the overall perception of the layout so that a better reading of the original landscape is given in winter when the trees are bare.

Continue in the Next Part