Architecture

General design

The design and decoration of the Nasrid palaces are a continuation of Moorish (western Islamic) architectural traditions from earlier centuries while developing their own unique characteristics. The combination of carefully proportioned courtyards, water features, gardens, arches on slender columns, and intricately sculpted stucco and tile decoration gives Nasrid architecture an ethereal and intimate quality. Walls were constructed mostly using rammed earth, lime concrete, or brick with a coating of plaster and roofs and ceiling coverings of wood—most of pine for doors and window shutters.

Nasrid architecture emphasized buildings as interior experiences and focused decoration inside. A rectangular courtyard, often provided with a pool, fountain, or water channel at its center, formed the basic unit of Nasrid palace architecture. Courtyards usually had halls on two or four sides and were sometimes preceded by arcaded porticoes.

Many of the buildings had a mirador, a room extending outward to provide panoramic views of gardens or the city. The buildings had a harmonious visual quality because the architecture followed a mathematical proportional system.

Courtyard arrangement, windows placement, and water features were well-designed to accommodate the climate, which ensured cooling and ventilation during summer while reducing cold drafts and maximizing sunlight in winter. Rooms on the upper floors were smaller and more enclosed, which made them more suitable for use in colder seasons.

Courtyards were generally oriented north to south, thereby ensuring direct sunlight on the main halls at midday in winter time. During summer, these porticoes fronting them blocked the sun at high midday positions, maximising comfort and functionality.

Architects and poets

Little is known about the architects and craftsmen responsible for building the Alhambra, but more is written about the Dīwān al-Ins͟hā’, or chancery. This institution seems to have increasingly been called in on to take an ever-greater role in designing buildings, probably because the decoration of the Alhambra was so strong on inscriptions. Its head often was the sultan’s vizier, or prime minister.

Although not architects in the classical meaning of the word, their tenures often overlapped with major construction phases, which implies that they likely managed the projects. Several of the most prominent are also known to have produced much of the Alhambra’s decorative inscription poetry: Ibn al-Jayyab, Ibn al-Khatib, and Ibn Zamrak.

- Ibn al-Jayyab was several times the chancery head between 1295 and 1349, thus serving under six sultans from Muhammad II up to Yusuf I.

- Ibn al-Khatib served as head of the chancery and vizier at various times between 1332 and 1371, mostly under Yusuf I and Muhammad V.

- Ibn Zamrak acted as vizier and head of the chancery from time to time during the period 1354-1393, in the reigns of Muhammad V and Muhammad VII.

These men shaped the aesthetic and literary expressions of the Alhambra while exercising their governmental functions to complement its lasting beauty.

Decoration

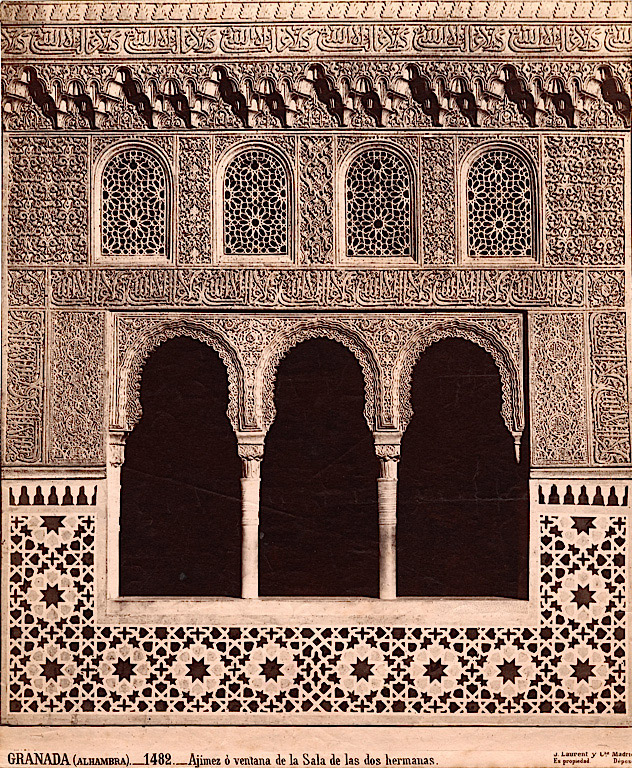

The prominent wall decorations in the Alhambra included carved stucco (yesería in Spanish) and mosaic tilework (zilīj or zellij in Arabic, alicatado in Spanish). Ceilings were usually made of wood, which was frequently decorated with carved and painted ornaments. Tile mosaics and wooden ceilings often displayed geometric patterns.

- Tilework was often used for lower walls and floors.

- Stucco, besides adorning top walls of buildings, could be moulded in designs ranging from vegetal arabesques (‘atauriques’ – from the Arabic root word of al-tawrīq meaning foliage), to epigraphic designs wherein the epigraphy features some form of inscription and to even geometric shapes and sebka motifs comprising an interlace lozenge pattern.

Stucco was also modeled in intricate, three-dimensional muqarnas, known as mocárabes in Spanish, which added both depth and visual complexity.

Of the many features that gave Alhambra its unique flair was the use of massive, inscribed Arabic inscriptions on many walls. These included passages of the Qur’an, verse by Nasrid court poets, and the repeated motto of the Nasrid:

\”Wa la ghalib illa-llah\” (Arabic: ولا غالب إلا الله), which means “And there is no victor but God.”

It was a fusion of the artistic and religious aspects that created such a richly symbolic environment in the Alhambra.

White marble, extracted from Macael in the province of Almería, was the preferred material for the Alhambra’s slender columns and for fountains. Column capitals were decorated and had two parts:

- Lower cylindrical part: It was decorated with sculpted stylized acanthus leaves.

- Upper cubic section: Here there appear the themes of a plant and geometrical motifs. On the base or on top, along the capitals, usually ran inscriptions, as the Nasrid motto, “Wa la ghalib illa-llah”, “And there is no victor but God.

It combined artistic detail with symbolic inscriptions to add elegance and meaning to the architectural elements of the Alhambra.

The stucco decorations, wooden ceilings, and marble capitals of the Alhambra, which often appear colorless or monochromatic today, were originally painted in vibrant and bright colors. Primary colors—red, blue, and gold (in place of yellow)—were used prominently and carefully juxtaposed to achieve a visually harmonious balance. Other colors were subtly applied in the background for depth and nuance to the overall aesthetic. These vivid colors added to the details and made the Alhambra a vibrant, rich, and energetic building during its time.

Inscriptions

The Alhambra demonstrates a number of Arabic epigraphy styles that thrived under the Nasrid dynasty, especially during the periods of Yusuf I and Muhammad V. According to scholar José Miguel Puerta Vílchez, the walls of the Alhambra can be compared to the pages of a manuscript, with zilīj-covered dados compared to geometric manuscript illuminations and epigraphical designs in the palace with calligraphic motifs in contemporary Arabic manuscripts. The inscriptions often ran in vertical or horizontal bands or were enclosed within cartouches of round or rectangular shapes, blending textual and architectural artistry seamlessly.

Most of the important inscriptions in the Alhambra employ Naskhi or running script, which became the most widely used script after the early Islamic period. Thuluth is a form of the running script used for official or formal documents, especially in the introductions of letters written by the Nasrid chancery. A significant number of inscriptions in the Alhambra are a combination of Naskhi-Thuluth.

Bands of cursive script frequently alternate with friezes or cartouches of Kufic script, the oldest form of Arabic calligraphy. By the 13th century, however, Kufic scripts in the western Islamic world had become increasingly stylized in architectural contexts, often to the point of near illegibility.

The Alhambra features numerous examples of “Knotted” Kufic, an elaborate style where the letters interlock in intricate knots. These letter extensions sometimes evolve into abstract motifs or serve as the edges of a cartouche that frames the rest of the inscription, seamlessly blurring textual and decorative elements.

The inscriptions of the Alhambra range from devout, regal, votive, and Qur’anic phrases and sentences in arabesques carved into wood and marble and glazed onto tiles. Poets of the Nasrid court, like Ibn al-Khatīb and Ibn Zamrak, wrote poems for the palace.

Another important characteristic of these inscriptions is their self-referential quality and use of personification, whereby certain poems, as in the case of those found in the Palace of the Lions, speak as if the palace or room itself were writing to the reader, often in the first person.

Most of the poetry is written in Nasrid cursive script, whereas foliate and floral Kufic inscriptions are mainly used as decoration. The inscriptions can take the form of arches, columns, enjambments, and even “architectural calligrams.” The words “blessing” (بركة, baraka) and “felicity” (يمن, yumn) serve as ornamentation motifs in arabesques that are scattered throughout the palace, written in Kufic script.

These inscriptions and their environments were originally painted vividly. Scholars note that letters were usually gilded or silvered or painted in white with black outlines to draw attention to them. The backgrounds, often painted in red, blue, or turquoise, were often decorated with other colors that gave a bright and striking view of the intricate designs.

Main structures

Entrance gates

The main gate of the Alhambra, also called the Puerta de la Justicia (Gate of Justice) or Bab al-Shari’a (Arabic: باب الشريعة, meaning “Gate of Shari’a (law)”), was the main entrance on the south side of the walled complex. Built in 1348 during the reign of Yusuf I, this impressive structure features a large horseshoe arch leading into a steep, bent passageway. The passage turns 90 degrees to the left and then 90 degrees to the right, with an opening above designed for defenders to drop projectiles onto potential attackers below.

Two symbolic carvings are found on the gate: a hand with five fingers, symbolizing the Five Pillars of Islam, is located above the archway on the exterior façade, while a key, another symbol of faith, is positioned above the archway on the inner façade. A Christian-era sculpture of the Virgin and Christ Child was later added inside the gate within a niche, reflecting the site’s later history under Spanish rule.

Near the exterior of the gate stands the Pilar de Carlos V, a Renaissance-style fountain originally built in 1524 and later modified in 1624, adding to the Renaissance influence surrounding the Alhambra.

At the end of this passage from the Puerta de la Justicia is the Plaza de los Aljibes (\”Place of the Cisterns\”), a big empty space separating the Alcazaba from the Nasrid Palaces. It is named after one significant cistern built around 1494 and commissioned by Iñigo López de Mendoza y Quiñones. This cistern was one of the first major works undertaken in the Alhambra after the 1492 conquest and helped fill a previously existing gully between the Alcazaba and the palaces.

On the east side of the square stands the Puerta del Vino (“Wine Gate”), which gives access to the Palace of Charles V and the former residential neighborhoods (the medina) of the Alhambra. The gate is dated to the period of Muhammad III, but the decoration spans several periods. The inner and outer facades of the gate have ceramic decoration filling the spandrels of the arches and stucco decoration above. On the western side of the gate is a carving of a key symbol, like that seen on the Puerta de la Justicia.

The other big entrance to the Alhambra is the Puerta de las Armas (“Gate of Arms”), which is located on the north side of the Alcazaba. A ramp with a walled street leads out from the gate towards the Plaza de los Aljibes and the Nasrid Palaces.

Originally, Puerta de las Armas acted as the principal access of the complex for ordinary townsfolk of the city as this could be reached directly from the Albaicín side; after the Christian conquest Puerta de la Justicia was the favored access route of Ferdinand and Isabella.

Built in the 13th century, the Puerta de las Armas is one of the oldest structures in the Alhambra and closely resembles the Almohad architectural tradition, which was there before the Nasrids. The exterior façade of the gate is decorated with a polylobed moulding and glazed tiles placed in a rectangular alfiz frame. On the inside of the gate’s passage, there is a dome painted to imitate the appearance of red brick, a decoration common to the Nasrid period.

Two other exterior gates existed, the two situated further to the east. On the north side lies the Puerta del Arrabal (“Arrabal Gate”), which leads to the Cuesta de los Chinos (“Slope of the Pebbles”), the ravine between the Alhambra and the Generalife. This gate was probably built by Muhammad II and served the first palaces of the Alhambra, erected at this site during his rule. The gate was completely changed at the later stage of Christian era of the Alhambra.

At the south side is the Puerta de los Siete Suelos meaning the \”Gate of Seven Floors”, which was all but annihilated by detonations put by the departing French troops during 1812. The modern gate was reassembled in the 1970s using residual parts with ancient engravings to describe the original gate.

The original gate was probably built in the mid-14th century, and its original Arabic name was Bab al-Gudur. This gate would have served as the main entrance to the medina, the area occupied by industries and the houses of workers inside the Alhambra. It was also through this gate that the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, first entered the Alhambra on January 2, 1492.

Alcazaba

The Alcazaba or citadel is the oldest part of the Alhambra today. It was the centerpiece of the complex fortifications that protected the area. Its tallest tower, the Torre del Homenaje (“Tower of Homage”), stands 26 meters (85 feet) high and served as the keep and military command post of the complex.

It might also have been the first abode of Ibn al-Ahmar inside the Alhambra when the complex was being built. The Torre de la Vela, the westernmost tower at 25 meters (82 feet), served as a watchtower. The flag of Ferdinand and Isabella was first waved over the Torre de la Vela on January 2, 1492, marking the fall of Granada to the Spanish.

Later in the year, the bell was mounted on top of the tower, where it was tolled at regular intervals daily and on ceremonial occasions throughout the centuries. In 1843, the tower was added to the city’s emblem.

Inside the inner fortress enclosure was the residence district, which held within it the elite Alhambra guards. Urban commodities such as a public kitchen, a hammam, a cistern supply of water, and some underground rooms that worked like dungeons and silos featured in this area.

Nasrid palaces

The royal palace complex of the Alhambra is divided into three parts, from west to east: the Mexuar, the Comares Palace, and the Palace of the Lions. Together, these palaces are referred to as the Casa Real Vieja (“Old Royal Palace”), in order to distinguish them from the newer palaces built alongside them during the Christian Spanish period.

Mexuar

The Mexuar is the westernmost part of the Alhambra palace complex. It was similar to the mashwars (or mechouars) of royal palaces in North Africa. It was first built as part of the larger complex begun by Isma’il I, which included the Comares Palace.

The Mexuar housed many of the administrative and public functions of the palace, such as the chancery and the treasury. The configuration of its layout was composed of two successive courtyards and then a major hall, all aligned from west to east along the central axis.

Today, only a few vestiges of the two western courtyards of the Mexuar remain, namely their foundations, a portico, and the water basin of a fountain. The main hall is called the Sala del Mexuar or Council Hall, which was a throne hall where the sultan received and judged petitions. This hall also led to the Comares Palace through the Cuarto Dorado section on its eastern side.

Many parts of the Mexuar had to be considerably altered in the aftermath of the Reconquista. In particular, the Sala del Mexuar was transformed into a Christian chapel, and the Cuarto Dorado was extended to make it a dwelling house. Those extensions were removed in the restorations of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Water supply system

The Acequia del Sultan, also called the Acequia del Rey or Acequia Real, supplied water to both the Alhambra and the Generalife and is still in use largely intact today. Water for this acequia comes from the Darro River, which is located about 6.1 kilometers east of the Alhambra in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

A smaller branch, the Acequia del Tercio, branches off some kilometres upstream. This latter follows the higher ground, arriving at the top of the Generalife palace and gardens. The main branch follows the lower ground to supply the Generalife palace and its celebrated Patio de la Acequia. Both followed generally a surface course but there are sections that had been directly tunnelled into the bedrock.

After reaching the Generalife, the canals turn southeast and run past the gardens. They then merge before turning back towards the Alhambra, where the water enters through an arched aqueduct next to the Torre del Agua (‘Water Tower’) at the eastern tip of the Alhambna. From here, the water flows through the citadel through a complex system of conduits (acequias) and water tanks (albercones), which create the famous interplay of light, sound, and surface that characterizes the palaces.

Historic furnishings and art objects

Whereas the walls and rooms of the Alhambra are empty of furniture now, they would have been ornamented and full of objects such as carpets, floor cushions, and tapestries or other objects that would hang on the walls. The practice of sitting on the floor accounts for why some of the windows in the miradors (lookout rooms) were located at a low level, aligned with the eyeline of seated persons.

Among the best-known objects from the Nasrid palaces are the “Alhambra vases,” a kind of large Hispano-Moresque ware from the Nasrid period that were mainly kept in the Alhambra. They were held on show in parts of the palace, probably in the corners of rooms. What their practical function, if any, was is uncertain but they probably served as complements to the architecture.

They stood on average at about 125 centimeters tall, being the largest lustreware pieces ever made. They are shaped like amphorae with narrow bases, bulging bodies, and narrow ribbed necks flanked by flat handles shaped like wings. They were decorated with Arabic inscriptions and other motifs, with the most common colors being cobalt blue, white, and gold.

Ten vases of this type have survived and started to be recorded in the 18th century, finding their way into museums afterwards. The earliest examples date back to the late 13th or early 14th century, but the most elegant examples date from the late 14th or early 15th century.

Precise information about where exactly these were produced is unknown due to the presence of numerous centres of ceramic production throughout the Nasrid kingdom, particularly at Granada and Málaga. One of the best examples is the Vase of the Gazelles, dated to the 14th century, which currently is kept at the Alhambra Museum and stands 135 centimeters tall, named after an image of confronted gazelles on the body.

Small jugs and vases were also kept in niches in the walls and doors of many rooms in the Alhambra. A taqa, or niche set into the wall under an archway in the jambs, was another typical feature of Nasrid architecture where such jugs were kept, possibly holding water for visitors. There are examples of these niches in the door leading into the Hall of Ambassadors.

The most important surviving artifact of the Alhambra is a magnificent bronze lamp which originally hung in the central mosque, dating back to 1305. The central body of the lamp is conical, attached to a shaft or stem with which it is surmounted by small spherical sections.

The bronze is pierced to produce Arabic inscriptions in Naskhi script and an arabesque vegetal background motif. After the conquest of 1492, it was confiscated and became part of the treasury of Cardinal Cisneros. Today it is housed in the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid; a replica is kept in the Alhambra Museum.

Continue in the Next Part