(Part:-2)

Lack of food and hostilities

The colony’s over-reliance on Secotan food probably contributed to the tense ties between the colony and the Secotan by spring. It seems that Wingina’s opposition to the English was influenced by the passing of Granganimeo, a strong supporter of the colony. Wingina created a new temporary tribal capital on Roanoke Island and renamed himself “Pemisapan” (“one who watches”), implying a new philosophy of caution and vigilance. At first, the English were unaware that these changes threatened their interests.

Regarding a proposal to explore the mainland outside of Secotan territory, Lane conferred with Pemisapan in March. Pemisapan endorsed the proposal and informed Lane that three thousand warriors had assembled at Choanoac and that Menatonon, the Chowanoke leader, was gathering with his supporters to organize an attack on the English. To make sure that both sides would anticipate conflict, Pemisapan informed Menatonon that the English would be arriving at the same time.

Representatives of the Chowanoke, Mangoak, Weapemeoc, and Moratuc were present when Lane’s well-armed group reached Choanoac. Lane took them by surprise because this group was not preparing an attack. Menatonon, whom he seized with ease, told him that Pemisapan had first called for the council.

By providing information on profitable prospects in areas the English had not yet explored, Menatonon soon won Lane’s trust. He warned that Lane should bring a sizable army if he wanted to establish contact with the wealthy and influential monarch to the northeast, who was most likely the Powhatan’s commander.

Apparently supporting English aspirations of discovering access to the Pacific Ocean, Menatonon also confirmed reports Lane had heard of a sea just beyond the head of the Roanoke River. Skiko, the chief’s son, told Lane of a location to the west known as “Chaunis Temoatan” that was abundant in a precious metal that Lane believed may be copper or possibly gold.

With this knowledge in hand, Lane drew up a comprehensive strategy that called for his troops to split up into two parties and relocate to Chesapeake Bay, one moving north along the Chowan River and the other along the Atlantic coast. But Grenville had assured him that new supplies would reach the colony by Easter, so he chose to postpone this trip until then. Meanwhile, Lane had Skiko returned to Roanoke as a captive and ransomed Menatonon.

In pursuit of Chaunis Temotan, he and forty men traveled almost 100 miles (160 km) up the Roanoke River, but all they saw were abandoned settlements and warriors waiting in ambush. Lane had anticipated that the Moratuc would supply him with food as he traveled, but Pemisapan had informed the villagers to leave the river with their food since the English were unfriendly.

Shortly after Easter, half-starved and without anything, Lane and his group returned to the colony. Pemisapan had been planning to remove the Secotan from Roanoke Island and abandon the colony to starve while they were away, and there had been allegations that they had been slain. Grenville’s resupply fleet, which had not even left England yet, was nowhere to be seen. Lane claims that Pemisapan changed his mind about his objectives after being shocked to learn that Lane had survived the Roanoke River mission.

One of Pemisapan’s council elders, Ensenore, supported the English. Later, Lane was told by a Menatonon emissary that Okisko, the Weapemeoc chief, had sworn allegiance to Sir Walter Raleigh and Queen Elizabeth. Pemisapan was further dissuaded from carrying out his plans against the colony by this change in the regional power dynamics. Instead, he gave his people instructions to construct fishing weirs for the settlers and plant crops.

The English and Secotan’s rekindled agreement did not last long. Ensenore passed away on April 20, robbing the colony of its final defender inside Pemisapan’s inner circle. Having spent time with the English, Wanchese had become a senior advisor and had grown to believe that they were a threat.

Pemisapan ordered the Secotan to stop selling food to the English, demolished the fishing weirs, and withdrew them from Roanoke. The English were unable to grow enough food to support the colony on their own. In the Outer Banks and on the mainland, Lane gave his soldiers orders to disperse into small groups and scrounge and beg for food.

Skiko remained a captive held by Lane. Skiko tried to respect his father’s desire to keep ties with the colony, even though Pemisapan met with him frequently and thought he was sympathetic to the anti-English cause. Skiko notified Lane that Pemisapan will convene a meeting of the war council with several regional powers on June 10.

Pemisapan was able to provide significant inducements to other tribes to join him in a last effort against the English by using the copper the Secotan had acquired from trade with the colony. While individual Weapemeocs were allowed to participate, Oksiko chose not to. The attack strategy was to signal for a broad assault on the remaining leaders after ambushing Lane and other important leaders while they were sleeping at the colony. In order to pressure Pemisapan, Lane used this intelligence to send false information to the Secotan, claiming that an English fleet had arrived.

The prospect of English reinforcements drove Pemisapan to expedite his plans, and on May 31 he assembled as many supporters as he could for a summit at Dasamongueponke. In an attempt to stop the warriors at Roanoke from warning the mainland the next morning, Lane assaulted them that evening.

Under the guise of discussing a Secotan attempt to release Skiko, Lane, his senior commanders, and twenty-five men paid Dasamongueponke a visit on June 1. Lane signaled his soldiers to strike when they were accepted into the council. After being shot, Pemisapan ran into the woods, but Lane’s men found him and returned with his severed head. Outside the fort of the colony, the head was impaled.

Evacuation

Sir Francis Drake’s fleet, returning to England following victorious engagements in Santo Domingo, Cartagena, and St. Augustine, was contacted by the colonists in June. Drake had obtained hardware, slaves, and refugees during his operations with the intention of transporting them to Raleigh’s colony. Drake consented to abandon one of his ships, the Francis, and four months’ worth of supplies after hearing of the colony’s troubles. But the Francis was swept out to sea as a storm struck the Outer Banks.

Drake consented to transport Lane’s troops back to England when he convinced them to leave the colony following the storm. They were joined by Manteo and Towaye, an associate. After being abandoned, three of Lane’s colonists were never heard from again. What happened to the slaves and refugees Drake intended to house in the colony is unknown because it was abandoned.

Drake may have left them on Roanoke with some of the items he had previously reserved for Lane, but there is no evidence that they arrived in England with the fleet. In July 1586, Drake’s ship arrived in England with Lane’s colonists. The colonists brought potatoes, maize, and tobacco to England when they first arrived.

Grenville’s detachment

Only a few days after Drake left the colony, Raleigh despatched a lone supply ship to Roanoke. The team departed after failing to locate any sign of the colonists. A year’s supply and 400 soldiers for reinforcements were ultimately brought in by Grenville’s rescue fleet two weeks later.

Three indigenous were questioned by Grenville after a protracted search, and one of them eventually provided a description of the evacuation. In order to preserve an English presence and defend Raleigh’s claim to Roanoke Island, the fleet left behind a small detachment of fifteen soldiers when it returned to England.

Shortly after Grenville’s fleet departed, an alliance of mainland tribes assaulted this detachment, according to the Croatan. Two of the assailants, who appeared to be unarmed, came to the tent and sought to meet with two Englishmen in a calm manner while the other five were out collecting oysters. An Englishman was killed by a Native American who was carrying a wooden sword. The other Englishman retreated to alert his squad, but another 28 attackers came forward.

The home where the English kept their food supplies was set on fire by the locals’ burning arrows, compelling the troops to use whatever weapons they had on hand. The other nine Englishmen retreated to the beach and left the island in their boat when a second Englishman was slain. After picking up their four fellow countrymen who had returned from the stream, they proceeded into Port Ferdinando. No one ever saw the thirteen survivors again.

Lost colony

Hakluyt, Harriot, and White convinced Raleigh to try again even though the Lane colony had been abandoned. However, after the battle between Lane’s men and the Secotan and Wingina’s death, Roanoke Island would no longer be safe for English immigrants. Part of the reason Hakluyt suggested Chesapeake Bay as the location for a new colony was his belief that the Pacific coast was only a short distance away from the Virginia territory’s explored territories.

A corporate charter to establish “the Cittie of Raleigh” with White as governor and twelve assistants was approved by Raleigh on January 7, 1587. About 115 individuals, including White’s pregnant daughter Eleanor and her husband Ananias Dare, consented to join the colony. The majority of the colonists were middle-class Londoners who could have aspired to become landed gentry.

They also took along Manteo and Towaye, who had departed with Drake’s ship from the Lane colony. There was no organized military force there, but women and children were part of the festivities this time.

Three ships made up the expedition: the flagship Lion, which White commanded with Fernandes serving as master and pilot; a flyboat, which Edward Spicer commanded; and a full-rigged pinnace, which Edward Stafford commanded. On May 8, the fleet departed.

The flagship and pinnace moored at Croatoan Island on July 22. Before proceeding on to Chesapeake Bay, White intended to transport forty men on the pinnace to Roanoke, where he would confer with the fifteen soldiers Grenville had placed there. However, a “gentleman” on the flagship who was Fernandes’ representative told the sailors to abandon the colonists on Roanoke as soon as he boarded the pinnace.

White’s group found the location of Lane’s colony the next morning. The cottages were empty and overrun with melons, and the fort had been demolished. Except for human bones that White thought were the remains of one of Grenville’s men who had been slain by Native Americans, there was no indication that Grenville’s men had ever been there.

All of the colonists disembarked once the flyboat arrived on July 25. Soon after, a native killed colonist George Howe when he was alone in Albemarle Sound looking for crabs.

With Manteo’s assistance, White sent Stafford to mend fences with the Croatan. The Croatan explained how Grenville’s detachment had been assaulted by a group of mainland tribes under the leadership of Wanchese. Through the Croatan, the colonists tried to broker a peace but got no answer.

White launched a preemptive attack on Dasamongueponke on August 9, but the English unintentionally targeted Croatan looters since the enemy had fled the village out of fear of retaliation for Howe’s death. Once more, Manteo improved ties between the Croatans and the colonists. Manteo was baptized and given the title “Lord of Roanoke and Dasamongueponke” in recognition of his devotion to the colony.

Eleanor Dare became “the first Christian born in Virginia” when she gave birth to a girl named “Virginia” on August 18, 1587. Nothing further is known about Margery Harvye’s kid, although records show that she gave birth soon after.

The colonists had made the decision to go 50 miles (80 km) up Albemarle Sound by the time the fleet was getting ready to return to England. In order to convey the colony’s dire circumstances and request assistance, the colonists convinced Governor White to travel back to England. Reluctantly, White accepted, and on August 27, 1587, he set out with the fleet.

1588 relief mission

On November 5, 1587, White arrived back in England after a challenging voyage. By this point, news of the Spanish Armada preparing an assault had made its way to London, and Queen Elizabeth had made it illegal for any ship with the capacity to leave England in order to take part in the impending conflict.

White was allowed to go with Grenville aboard a resupply ship during the winter, when he was given permission to lead a fleet into the Caribbean to battle the Spanish. Unfavorable winds held the fleet in port until Grenville was given new instructions to stay and protect England, even though the fleet was scheduled to launch in March 1588.

White was allowed to carry the Brave and the Roe, two of Grenville’s smaller ships, to Roanoke since they were judged unfit for battle. Although the ships set sail on April 22, their captains made an effort to seize a number of Spanish vessels on the outbound journey (to increase their earnings).

French seafarers, often known as pirates, assaulted them on May 6 in the vicinity of Morocco. The ships were forced to return to England after almost two dozen crew members were slaughtered and the goods that were headed for Roanoke were seized. In order to concentrate on assembling a Counter Armada to invade Spain in 1589, England kept the shipping restriction in place after the Spanish Armada was routed in August. It was not until 1590 that White would be granted permission to try another resupply.

Spanish reconnaissance

Since Grenville’s conquest of Santa Maria de San Vicente in 1585, the Spanish Empire had been obtaining information about the Roanoke colonies. They were afraid that the English had set up a base for piracy in North America, but they couldn’t find it. They had no reason to believe that White’s colony would be set up in the same spot as Lane’s, or that Lane’s had been abandoned. The Spanish did, in fact, significantly exaggerate the English’s achievement in Virginia; there were reports that the English had found a diamond mountain and a path to the Pacific Ocean.

Vicente González was sent by Philip II of Spain to examine Chesapeake Bay in 1588 after a reconnaissance trip failed in 1587. González was unable to locate anything in the Chesapeake, but he happened to find Port Ferdinando in the Outer Banks on his way back. The harbor seemed deserted. González departed without carrying out a comprehensive inquiry.

The Spanish thought González had found the hidden English base, but Phillip refrained from launching an attack on it right once due to the Spanish Armada’s loss. According to reports, there was a plot in 1590 to demolish the Roanoke colony and establish a Spanish colony in Chesapeake Bay. However, this was just propaganda meant to divert English intelligence.

1590 relief mission

In the end, John Watts organized a privateering expedition, and Raleigh secured passage for White. The flagship Hopewell and the Moonlight would separate to transport White to his colony, while the other six ships in the fleet would spend the summer of 1590 assaulting Spanish strongholds in the Caribbean. However, Raleigh was in the process of handing over the business to new investors at the same time.

There is no evidence that White utilized the August 12 anchoring of Hopewell and Moonlight at Croatoan Island to get intelligence from the Croatan. While anchored at the north end of Croatoan Island on the evening of August 15, the workers noticed smoke plumes on Roanoke Island. The next morning, they looked into another smoke column on the southern end of Croatoan, but they couldn’t see anything.

The following two days were devoted to White’s landing party’s arduous and fatal endeavor to traverse Pamlico Sound. They rowed towards a fire they saw on the north end of Roanoke on August 17, but they arrived at the island after dark and chose not to take the chance of landing. on the hopes that the colonists would hear them, the men sang English songs while spending the night on their moored boats.

On the morning of August 18, his granddaughter’s third birthday, White and the others touched down. The group discovered new footprints in the sand, but no one got in touch with them. Additionally, they found the initials “CRO” engraved on a tree. When White arrived at the colony’s location, he observed that a barrier had been erected to protect the place.

The word “CROATOAN” was etched into one of the posts at the fencing’s entrance. Because they had agreed in 1587 that the colonists would leave a “secret token” identifying their location, or a cross pattée as a duress code, White was persuaded that these two inscriptions signified that the colonists had moved to Croatoan Island peacefully.

The search group discovered that dwellings had been disassembled and that anything that could be carried had been taken out of the palisade. Numerous sizable trunks had been unearthed and plundered, including three that belonged to White and contained the possessions he abandoned in 1587.

There were no boats from the settlement along the coast. Plans were planned to return to Croatoan the next day when the party returned to Hopewell that evening. But Hopewell only had one functional cable and anchor when its anchor cable broke. Due to the significant risk of shipwreck, the search operation was unable to proceed.

In order to reach a compromise with White, the Hopewell crew proposed that Moonlight spend the winter in the Caribbean and return to the Outer Banks in the spring of 1591. However, when Hopewell was blown off course and they had to halt in the Azores for provisions, their strategy was ruined. The ship was again forced to alter its route and arrive at England on October 24, 1590, as the storms prevented landfall there.

Scientific research

Lawson’s study in 1701 was the last major examination concerning the disappearance of the colonists in 1587. The 19th century saw a resurgence of interest in the Lost Colony, which ultimately prompted a variety of academic studies.

1800s–1950: Site preservation

Eventually, the ruins Lawson stumbled upon in 1701 were turned into a tourist destination. On April 7, 1819, U.S. President James Monroe paid a visit to the location. During the 1860s, tourists reported trenches being excavated nearby in quest of priceless artifacts and characterized the dilapidated “fort” as little more than an earthwork shaped like a little bastion.

Road construction and the 1921 silent film The Lost Colony’s production caused more harm to the location. J. C. Harrington promoted the preservation and restoration of the earthwork in the 1930s. With the designation of Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, the National Park Service took over management of the region in 1941. The earthwork was rebuilt in 1950 to try to restore it to its original dimensions.

1998: Climate research

In 1998, a group headed by archaeologist Dennis B. Blanton of the College of William & Mary and climatologist David W. Stahle of the University of Arkansas came to the conclusion that Tidewater had a severe drought from 1587 to 1589. They collected data from 1185 to 1984 by measuring the growth rings of a network of bald cypress trees. In particular, 1587 was recorded as the 800-year period’s worst growth season. The results were seen to be in line with the Croatan people’s worries over their food supply.

2005–2019: Genetic analysis

Roberta Estes, a computer scientist, established a number of organizations for genealogy research and DNA analysis since 2005. Numerous initiatives to create a genetic connection between the colonists and possible Native American descendants were spurred by her fascination with the loss of the 1587 colony.

Because so little of the colonists’ genetic material would be left behind after five or six generations, autosomal DNA analysis is unreliable for this purpose. Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA testing, on the other hand, is more accurate over extended periods of time. Getting a genetic point of comparison from the bones of a Lost Colonist or one of their descendants is the primary problem of this effort. Although it is possible to sequence DNA from bones that are 430 years old, no bones from the Lost Colony have been found to far. Furthermore, no live descendants had been found by the project as of 2019.

Archaeological research

1887–present: Archaeological evidence

Only after Talcott Williams found a Native American burial site on Roanoke Island in 1887 did archeological studies on the island start. When he went back to dig the fort in 1895, he discovered nothing noteworthy. In the 1990s, Ivor Noël Hume would uncover a number of interesting discoveries, but none of these could be conclusively connected to the colony in 1587 as opposed to the outpost in 1585.

In 1995, anthropologist David Sutton Phelps Jr. organized an excavation near Cape Creek in Buxton, North Carolina, following Hurricane Emily’s discovery of many Native American artifacts. In 1998, Phelps and his crew found what at first glance seemed like a gold signet ring with the 16th-century insignia of a Kendall family. Although the discovery was hailed as historic, Phelps failed to get the ring adequately analyzed and never published a report on his findings.

In 2017, X-ray examination revealed that the ring was made of brass rather than gold, and experts were unable to verify the purported link to Kendall heraldry. It seems more likely that the ring was transported to the New World later because of its low value and relative obscurity, which make it harder to definitively link it to any one individual from the Roanoke expeditions.

The fact that many similar objects might have come from the 1585 colony or from Native Americans who interacted with other European colonies during the same time period presents a substantial problem for archaeologists looking to learn more about the colonists of 1587.

According to Andrew Lawler, female remains buried in accordance with Christian custom (supine, in an east-west orientation) and dating to before 1650 (by which time Europeans would have spread throughout the region) would be an example of a conclusive find, as the colony in 1585 was exclusively male. Few human remains of any type, however, have been found in locations associated with the Lost Colony.

Shoreline erosion might be one reason for the severe lack of archeological remains. Between 1851 and 1970, Roanoke Island’s northern shore—where the Lane and White colonies were situated—lost 928 feet (283 meters). It is probable that parts of the towns, along with any relics or indications of life, are currently under water if this tendency is extended back to the 1580s.

2011–present; new archaeological sites

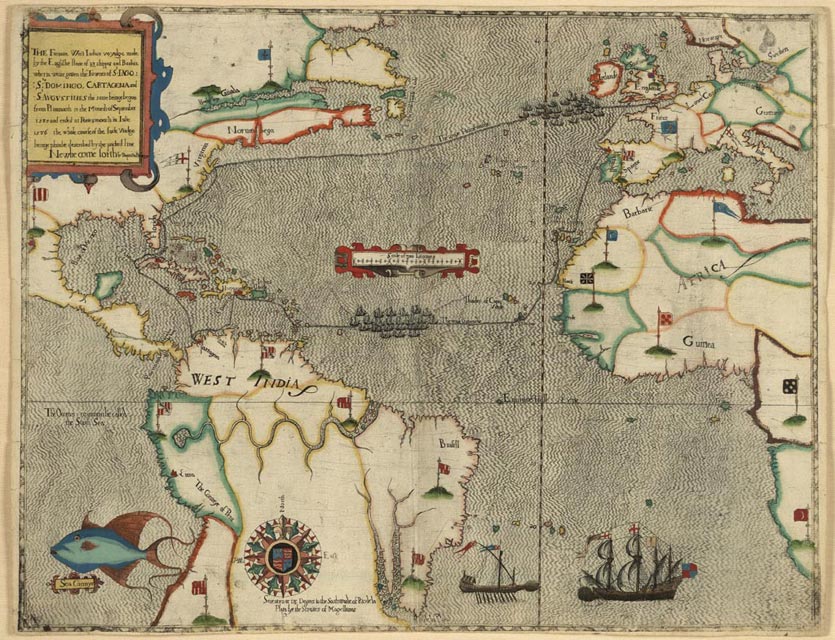

Two correction patches were discovered on White’s 1585 map La Virginea Pars in November 2011 by researchers at the First Colony Foundation. The British Museum used a light table to examine the original map at their request. It was discovered that one of the patches covered a sign for a fort near the head of Albemarle Sound, which is located at the meeting point of the Roanoke and Chowan rivers.

The patch itself also revealed the faint form of a fort, painted in what may be invisible ink. White could have been attempting to hide the fort from the Spanish, who viewed the colony as a danger, according to one scenario. Despite sending an expedition to destroy the colony, the Spanish were unable to locate the inhabitants.

Due to its lack of scale, the sign encompasses a region on the map that corresponds to hundreds of acres in Bertie County, North Carolina. Nonetheless, the site is thought to be in or close to the Weapemeoc settlement of Mettaquem, which dates back to the 16th century. As a crew was ready to dig where the sign pointed in 2012, archeologist Nicholas Luccketti proposed that they call the site “Site X,” as in “X marks the spot.” The site, which is close to the Native American town of Mettaquem, was excavated in 2015 by a team.

According to a statement released by the First Colony Foundation in October 2017, the discovery of pieces of Tudor weaponry and ceramics at Site X suggests that a small number of colonists lived there in peace. Convincingly ruling out the idea that such findings were brought to the region by the Lane colony in 1585 or the trade station founded by Nathaniel Batts in the 1650s is the challenge for this investigation. Plans to extend the study onto territory granted to North Carolina as Salmon Creek State Natural Area were announced by the Foundation in 2019.

Researchers think that fresh artifacts discovered in North Carolina in 2020 could belong to a colony of Lost Colony survivors. Approximately fifty miles west of Roanoke Island, they were discovered. Since subsequent settlers from other colonies, like Jamestown, would have different objects and materials than the Lost Colony residents—for instance, clay pipes, which were produced later—analysis of the artifacts centered on identifying whether they may be from the Lost Colony. Items were discovered by another researcher at a location around fifty miles south of Roanoke Island.

At the location of a Native American settlement on Hatteras Island, Mark Horton, an archaeologist from the University of Bristol, conducted another excavation and discovered European items, including pieces of a rifle and a sword. This might be definitive evidence that the settlers did, in fact, integrate with the Native Americans in the area.

In his book The Lost Colony and Hatteras Island, released in 2020, Scott Dawson details his and Horton’s search for colony-related items. Additionally, he authored pieces for magazines, such as American Heritage, which had a description of a number of important items. These contained a number of items that appeared to have been produced by Europeans, such as glass, an olive jar, and other manufactured goods.