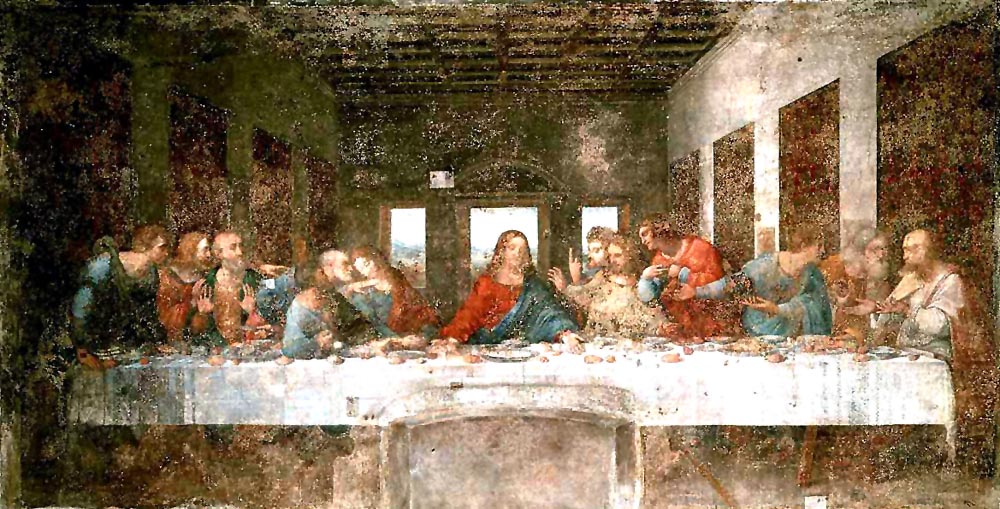

The Last Supper, also known as Il Cenacolo [il tʃeˈnaːkolo] or L’Ultima Cena [ˈlultima ˈtʃeːna], is a mural painting by Leonardo da Vinci, an Italian High Renaissance artist, that is kept in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. It was created somewhere between 1495 and 1498. According to the Gospel of John, the picture depicts the scenario of Jesus’ Last Supper with the Twelve Apostles, particularly the part when Jesus says one of his apostles would betray him.

It is one of Leonardo’s most well-known paintings and one of the most identifiable in the Western world because to its mastery of perspective, control of space, handling of motion, and intricate portrayal of human emotion.[2] According to some analysts, it was crucial in kicking off the shift into what is now known as the High Renaissance.

Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, Leonardo’s patron, commissioned the piece as part of a plan to renovate the church and associated convent buildings. It is painted using materials that allowed for numerous changes, such as pitch, mastic, and tempera on gesso, to accommodate his irregular painting schedule and many adjustments.

Despite many restoration attempts, the last of which was finished in 1999, very little of the original artwork is still there today due to the techniques employed, a number of environmental variables, and deliberate destruction. With the exception of the Sala delle Asse, Leonardo’s biggest piece is The Last Supper.

Painting

Commission and creation

The Last Supper is located on the end wall of the dining hall of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy, and it is 460 cm by 880 cm (180 in by 350 in). Despite the fact that the chamber was not a refectory when Leonardo painted it, the motif was conventional for refectories. While Leonardo was creating the picture, the main church structure was still being built. Ludovico Sforza, Leonardo’s patron, intended to transform the cathedral into a tomb for his family. Perhaps Donato Bramante’s ideas were modified to achieve this.

A smaller funerary chapel was built next to the cloister, but these designs were not completed. Sforza commissioned the picture to adorn the mausoleum’s wall. Sforza coats of arms are painted on the lunettes above the main artwork, which are created by the refectory’s triple arched roof. The Crucifixion painting by Giovanni Donato da Montorfano covers the opposite wall of the refectory. Leonardo added tempera figures of the Sforza family to the fresco, which has deteriorated similarly to The Last Supper.

Leonardo did not work on The Last Supper nonstop between approximately 1495 and 1498. Due to the destruction of the convent’s historical archives, the start date is uncertain. According to a document from 1497, the painting was almost finished at that time.

Leonardo apparently received a complaint about the delay from a prior from the monastery. In a letter to the monastery’s leader, Leonardo explained that he had been having trouble finding the ideal wicked face for Judas and that if he was unable to find one that matched his vision, he would utilize the features of the prior who had voiced his displeasure.

According to a 1557 article by Gian Paolo Lomazzo, Leonardo Zenale, a friend of Leonardo’s, suggested that he should not complete painting Christ’s face since “it would be impossible to imagine faces lovelier or gentler than those of James the Greater or James the Less.” Apparently Leonardo heeded the suggestion.

Moderate

Oil painting, which enables the artist to work slowly and make adjustments with ease, was Leonardo’s preferred medium. Neither of these goals is aided by fresco painting. Leonardo also aimed for chiaroscuro, which is a technique in which water-soluble colors are painted onto freshly laid parts of wet plaster every day, to generate a higher brilliance and intensity of light and shade than could be accomplished with fresco.

Leonardo painted The Last Supper in tempera, a medium typically used for panel painting, as opposed to the tried-and-true technique of painting on walls. A double coat of gesso, pitch, and mastic has been applied to the stone wall where the artwork is located.

To make the tempera that was placed on top more brilliant, he next used a white lead undercoat. Cennino Cennini had already described this technique in the fourteenth century. Cennini, however, suggested using a more surface-level substance for the finishing touches and characterized the method as riskier than fresco painting.

Topic

Each apostle’s response to Jesus’ prediction that one of them will betray him is depicted in The Last Supper. The news causes varying degrees of astonishment and rage in each of the twelve apostles. An unsigned fresco replica of Leonardo’s Cenacolo from the middle of the sixteenth century was used to identify the apostles by their names. Judas, Peter, John, and Jesus were the only people who had been positively identified prior to this. According to the heads of the apostles, from left to right:

- Three people—Bartholomew, Andrew, and James, son of Alphaeus—are taken aback.

- Another trio consists of John, Peter, and Judas Iscariot. Judas is in shadow, dressed in scarlet, blue, and green, and he appears distant and surprised by the abrupt disclosure of his scheme. He is holding a tiny bag, which could be a reference to his position as treasurer or the silver that was paid to him for betraying Jesus. He is also turning over the salt storage, which could be connected to the phrase “betray the salt” from the near-Eastern, which means to betray one’s lord. His head is the lowest vertically in the painting, and he is the only one with his elbow resting on the table. Peter appears to be wielding a knife and is wearing an angry expression, hinting at his violent response in Gethsemane when Jesus is arrested. In reference to John’s Gospel, where he instructs the “beloved disciple” to ask Jesus who is betraying him, Peter is bending over and caressing John on the shoulder. John, the youngest apostle, seems to swoon and tilt in Peter’s direction.

- Jesus

- The next trio is Philip, James the Greater, and Thomas. Thomas is obviously agitated, as evidenced by the raised index finger, which suggests that he finds the Resurrection unbelievable. James the Greater’s arms are raised in what appears to be shock. Philip, meanwhile, seems to be asking for an explanation.

- The last three are Simon the Zealot, Jude Thaddeus, and Matthew. Perhaps in an attempt to get a response to their earlier queries, Thaddeus and Matthew turn to face Simon.

Leonardo arranges the guests on one side of the table so that no one is facing away from the viewer, as is typical of other representations of the Last Supper from this era. White and blue stripes, which are frequently connected to Jews, make up the tablecloth. This is the only overt allusion to Jesus and his disciples’ ethnicity in the artwork.

By positioning Judas alone on the other side of the table from Jesus and the other eleven disciples, or by encircling every disciple with halos save Judas, the majority of earlier representations left Judas out. Instead, Leonardo makes Judas slant back into the darkness.

Thomas and James the Greater, who are on his left, react horrifiedly when Jesus points with his left hand to a piece of bread in front of them, anticipating that his betrayer will take the bread at the same moment that he does.

Distracted by John and Peter’s talk, Judas grabs for another piece of bread, failing to notice Jesus reaching out for it with his right hand (Matthew 26: 23). The vanishing point for all perspective lines is Jesus’s turned right cheek, which is highlighted by the lighting and angles.

Furthermore, as it “directs our attention to the face of Christ at the center of the composition, and Christ’s face, through his down-turned gaze, directs our focus along the diagonal of his left arm to his hand and therefore, the bread,” the painting showcased Leonardo’s skillful use of perspective.

According to reports, Leonardo drew inspiration for the painting’s figures from the likenesses of individuals in and around Milan. The prior of the monastery grumbled to Sforza about Leonardo’s “laziness” while he prowled the streets in search of a felon to serve as the model for Judas.

Leonardo said that the prior would be a good model if he could find no one else. Mathematician Luca Pacioli, a friend of Leonardo’s, described the painting as “a symbol of man’s burning desire for salvation” when it was being completed.

The past

Early copies

There are two known early copies of The Last Supper, which are thought to have been created by Leonardo’s helpers. The duplicates have survived with a great deal of original detail still there and are nearly the size of the original. The Royal Academy of Arts in London owns one by Giampietrino, while Cesare da Sesto’s piece is on display at the Church of St. Ambrogio in Ponte Capriasca, Switzerland. Andrea Solari painted a third copy (oil on canvas) in 1520, and it is on exhibit at the Leonardo da Vinci Museum at the Tongerlo Abbey in Belgium.

Damage and restorations

The masons packed the walls with moisture-retaining rubble because Sforza had wanted the church to be rebuilt quickly. Due to the thin external wall on which the painting was done, the effects of humidity were particularly noticeable, and the paint did not cling to it well. Due to the technique employed, the painting started to deteriorate shortly after it was finished on February 9, 1498. Louis XII considered taking the picture down from the wall and bringing it to France in 1499.

Gerolamo Cardano characterized the painting as “blurred and colorless compared with what I remember of it when I saw it as a boy” in 1532, indicating that it was beginning to flake as early as 1517. Less than 60 years after it was completed, in 1556, Giorgio Vasari said the painting had degraded to a “muddle of blots” with unintelligible figures. Gian Paolo Lomazzo claimed that “the painting is all ruined” by the latter part of the 16th century.

The irregular arch-shaped structure near the artwork’s center base is still visible after a doorway was cut through the (then unrecognizable) painting in 1652 and eventually bricked up. According to early copies, Jesus’ feet were positioned to represent the impending crucifixion. A drape was put over the picture in 1768 with the intention of protecting it, but instead it retained moisture on the surface and damaged the peeling paint everytime it was drawn back.

In 1726, Michelangelo Bellotti undertook the first restoration, applying oil paint to the missing areas and then varnishing the entire mural. Giuseppe Mazza, an otherwise unknown artist, attempted a second restoration in 1770 when first one did not hold up.

After removing Bellotti’s work, Mazza repainted the picture in its entirety; by the time he was stopped because of public outcry, he had redone all but three faces. The refectory served as a stable and armory for French revolutionary anti-clerical troops in 1796. They climbed ladders to scrape off the Apostles’ eyes and flung stones at the picture.

According to Goethe, a severe downpour in 1800 caused the room to fill with two feet of water. It is unknown whether any of the inmates may have harmed the painting during the time the refectory was used as a prison [when?].

Before determining that Leonardo’s piece was not a fresco, Stefano Barezzi, who was skilled at removing entire frescoes off their walls intact, was called in in 1821 to move the painting to a safer position. He severely damaged the center area. Barezzi then tried using glue to repair the damaged areas.

Luigi Cavenaghi meticulously examined the painting’s structure between 1901 and 1908 before starting to polish it. Oreste Silvestri stabilized some areas with stucco and performed additional cleaning in 1924.

The refectory was hit by Allied bombing on August 15, 1943, during World War II. The artwork was shielded from bomb splinters by protective sandbagging, but the vibration might have caused damage. Fernanda Wittgens, director of Brera, worked on Mauro Pellicioli’s clean-and-stabilize restoration from 1946 to 1954.

Pellicioli removed some of the overpainting and reapplied paint to the wall using a clear shellac, making it comparatively deeper and more vivid. The heads of Saints Peter, Andrew, and James, however, were somewhat different from the original design as of 1972 due to repainting carried out in several restorations.

Major restoration

By the late 1970s, the painting’s condition had significantly declined. Pinin Brambilla Barcilon oversaw a significant restoration project from 1978 to 1999 in an effort to restore the artwork and undo the harm that pollution and dirt had done.

Restoration efforts from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were likewise undone. The refectory was transformed into a sealed, climate-controlled space, which required bricking up the windows, because it had shown to be unfeasible to relocate the painting to a more controlled setting.

A thorough investigation was then conducted to ascertain the painting’s original shape using authentic cartoons kept in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle as well as scientific studies, particularly infrared reflectoscopy and microscopic core samples. Some regions were judged irreparable. Watercolor was used to re-paint these in muted hues that would be subtle enough to show they weren’t original artwork without being overpowering.

After 21 years of repair, the picture was put back on display on May 28, 1999. Intending guests could only remain for 15 minutes and had to make reservations in advance. The striking variations in hues, tones, and even some facial features caused a great deal of criticism when it was first revealed.

One particularly harsh critic had been James Beck, founder of ArtWatch International and professor of art history at Columbia University. ArtWatch UK director Michael Daley has also voiced dissatisfaction with the painting’s restoration. He has taken issue with the image’s modification of Christ’s right arm, which Daley refers to as “muff-like drapery” instead of a draped sleeve.

In culture

In Western culture, references, reproductions, and parodies of The Last Supper are common. Among the more noteworthy instances are:

Non-modern painting, mosaic, and photography

In the abbey of Tongerlo in Antwerp, Belgium, there is a copy of an oil painting from the 16th century. Numerous details that are no longer apparent on the original are revealed. Another life-sized replica created by Roman mosaic craftsman Giacomo Raffaelli (1809–1814) on Napoleon Bonaparte’s order is housed in Vienna’s Minoritenkirche.

Modern art

The Sacrament of the Last Supper, painted by Salvador Dalí in 1955, shows Jesus as clean-shaven and blond, pointing up to a ghostly torso while the apostles are seated around the table, their heads down so that no one can be recognized. It is said to be among the most viewed paintings in the National Gallery of Art’s collection in Washington, D.C.

The Last Supper was appropriated by Mary Beth Edelson in her 1972 work Some Living American Women painters / Last Supper, in which the heads of prominent female painters were collaged over the heads of Christ and his apostles.

Lynda Benglis, Louise Bourgeois, Elaine de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, Nancy Graves, Lila Katzen, Lee Krasner, Georgia O’Keeffe, Louise Nevelson, Yoko Ono, M. C. Richards, Alma Thomas, and June Wayne are among the artists who collaged over the heads of Christ and his apostles in Some Living American Women Artists / Last Supper. Additionally, the piece’s border features the images of other female artists; in total, eighty-two female artists are featured in the image.

Addressing the oppression of women through religious and art historical symbolism, this artwork became “one of the most iconic images of the feminist art movement.”

Using painted and sketched wood, plywood, brick, plaster, and aluminum, sculptor Marisol Escobar created a life-sized, three-dimensional sculpture of The Last Supper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is home to the 1982–84 piece Self-Portrait Looking at the Last Supper.

Andy Warhol was commissioned by art dealer Alexander Iolas to create a series of paintings inspired by The Last Supper, which were initially displayed in Milan in January 1987. It would be the artist’s final series before he passed away.

Some Mystery about The Last Supper (Leonardo)

1. Why Did Leonardo Choose the Last Supper Scene?

- Scholars debate why Leonardo da Vinci selected this specific, emotionally charged scene for depiction, given his tendency to diverge from traditional religious art.

2. What Symbolism is Hidden in the Bread and Wine?

- Leonardo’s placement of the bread and wine, central to Christian Eucharist, has sparked intrigue, with some interpreting hidden messages in their positioning and symbolism.

3. Does the Knife Point to Judas or Jesus?

- A knife is visible in the painting, held ambiguously behind Judas, leading to questions about whether it symbolizes a threat to Judas or foreshadows the betrayal of Jesus.

4. Why is There a Lack of Haloes?

- Unlike most religious art of the period, Leonardo chose not to give Jesus or the apostles haloes, which raises questions about his intent and possible critique of religious symbolism.

5. Was Leonardo Embedding Mathematical Codes?

- The painting’s geometry has led some art historians to suggest Leonardo embedded complex codes, possibly to reflect divine proportion or reveal hidden messages.

6. Did Leonardo Project His Own Views?

- Leonardo’s unconventional portrayal of this sacred scene has led some to believe that he infused the work with his personal religious views or even skepticism.

7. What Happened to Judas’s Left Arm?

- Judas’s left arm is either missing or at a strange angle, sparking theories that Leonardo intended it as a visual metaphor for his isolation or “lost” status.

8. The Mysterious Disembodied Knife Hand

- Behind Judas, a hand holding a knife is visible, but no body is connected to it, leading to endless speculation about who holds it and why it’s there.

9. Theories of Fibonacci Sequence Use

- The painting’s proportions have led some to believe Leonardo incorporated the Fibonacci sequence, adding a layer of mathematical mystery to the work.

10. Hidden Musical Notes?

- In 2007, a musician theorized that the positioning of hands and bread could represent musical notes, creating a “song” that may hold hidden messages.

11. Who is the Apostle Next to Jesus Really?

- The figure to Jesus’ right is often identified as John, but some speculate it could represent Mary Magdalene, sparking debate about possible hidden identities.

12. Does the Scene Depict an Anachronism?

- The table, clothing, and architecture all reflect Leonardo’s time, not ancient Jerusalem, prompting theories about Leonardo’s intent in making these choices.

13. The Mirror Effect Theory

- Some researchers suggest that The Last Supper contains mirror-image symmetries, believed by some to hint at hidden messages when viewed in reverse.

14. What is the Meaning Behind Judas’s Position?

- Judas is placed slightly apart from the group and holds a small bag, presumably with silver coins, raising questions about whether Leonardo encoded further symbolism in his pose.

15. The Mystery of Jesus’s Hands

- Jesus’s hands are spread apart on the table, possibly symbolizing openness or surrender. However, some see them as holding secret symbols or mathematical alignments.

16. Does the Background Hold a Secret Scene?

- The background has been scrutinized for hidden shapes and symbols, with some suggesting it may represent Jerusalem, heaven, or even a hidden narrative.

17. The Vanishing Apostles’ Feet

- Feet of some apostles are obscured or missing due to damage and restoration, raising questions about their original position and if they held symbolic meaning.

18. Is There a Secret Message in Peter’s Hand Gesture?

- Peter’s hand is positioned near John in a protective or threatening way, leading to interpretations that it hints at internal conflict among the apostles.

19. What is the Nature of Jesus’s Gaze?

- Jesus’s gaze appears calm yet distant, with some interpreting it as resignation or divine foresight, while others see it as a message of peace.

20. The Sacred Geometry Theory

- Some theorists propose that the painting’s layout follows sacred geometric principles, possibly reflecting Leonardo’s scientific and spiritual interests.

21. Could There Be a 13th Apostle?

- Theories suggest that a missing or hidden 13th figure might be subtly represented, symbolizing the presence of someone like Mary Magdalene or even Leonardo himself.

22. Is Leonardo Embedding Himself as a Figure?

- Some speculate that Leonardo painted himself into the scene, either as an apostle or a hidden face, leading to debates about his intended role in the composition.

23. The Mystery of the Three Windows

- The three windows behind Jesus are often interpreted as symbols of the Holy Trinity or heaven, but they have also been seen as possible gateways to hidden meanings.

24. Could Judas Be a Self-Portrait?

- A few scholars propose that Judas’s face resembles self-portraits of Leonardo, speculating that he may have associated himself symbolically with the idea of betrayal.

25. The Odd Placement of John

- John’s posture and the physical closeness to Jesus has raised questions about why Leonardo chose this arrangement, sparking ideas of hidden intimacy or symbolism.

26. Was the Scene Based on Leonardo’s Own Social Circle?

- Some believe Leonardo used friends or contemporaries as models for the apostles, implying that he may have encoded their identities within the figures.

27. A Missing Goblet?

- Some argue that the lack of a prominent goblet in front of Jesus implies Leonardo intentionally left out the Holy Grail, possibly symbolizing a hidden message.

28. What Did Leonardo Want to Convey in the Apostles’ Hands?

- The apostles’ hands seem almost choreographed in their gestures, leading to speculation that their positions carry significant hidden messages.

29. Hidden Feminine Symbolism?

- Interpretations argue that certain figures, like the one traditionally believed to be John, are presented in a way that could symbolize feminine or androgynous qualities.

30. Did Leonardo Predict the Apostles’ Fates?

- Scholars have noted that the apostles’ individual expressions may predict their fates, with some suggesting Leonardo’s foresight or hidden prophecies.

31. Is There a Hidden Link to the Shroud of Turin?

- Some believe that Leonardo used the Shroud of Turin as a reference for Jesus’s face, creating a mystical link between the two works.

32. The Secret Society Theory

- Theories suggest Leonardo’s involvement in secret societies, like the Priory of Sion, which may have influenced cryptic messages within the painting.

33. Could This Be a Map to a Hidden Treasure?

- A longstanding theory posits that the painting might contain a cryptic map, possibly leading to a hidden artifact or treasure.

34. The Theory of Twin Figures

- Some suggest that the figures in the painting reflect pairs or “twins,” which could symbolize duality or hidden relationships among them.

35. The Influence of the Golden Ratio

- There is speculation that Leonardo used the Golden Ratio in the painting’s composition, aiming to reflect divine harmony in its structure.

36. The Table’s Divisions as Hidden Code

- The table in The Last Supper has been interpreted as a possible code, with scholars speculating that its structure holds a symbolic or mathematical meaning.

37. What Does the Lack of Light Mean?

- The lighting in the painting is often seen as unusual for such a dramatic scene, leading to questions about Leonardo’s intentions with shadow and illumination.

38. The Theory of a Mirror Image

- Some suggest that The Last Supper contains hidden images or reversed figures when viewed in a mirror, which could reveal alternate messages.

39. Are There Astrological Signs Embedded?

- Certain researchers argue that the apostles’ positions correlate with zodiac signs, leading to theories about Leonardo embedding astrology within the work.

40. A Message Hidden in Peter’s Clothing?

- Peter’s garments have been analyzed for patterns, with some suggesting that they may contain symbols or shapes with hidden meanings.

41. Does Jesus’s Pose Resemble a Cross?

- Some art historians suggest that Jesus’s pose, with arms extended, mimics the shape of a cross, possibly foreshadowing the crucifixion.

42. Is There a Hidden Message in the Architecture?

- The arches, windows, and walls in the background have been studied for hidden symbols or messages, leading some to propose connections to Leonardo’s architectural interests.

43. The Unexplained Motion in Each Figure

- The apostles appear to be captured in mid-motion, as if frozen in a specific moment, prompting speculation about what exactly Leonardo aimed to capture.

44. Could This Painting Represent a Conspiracy?

- Some theorists propose that The Last Supper contains clues suggesting a religious conspiracy or secret message against the Church’s teachings.

45. Does the Positioning of the Apostles Hold a Numerical Code?

- The grouping of apostles in threes has led to theories that this reflects a hidden numerical code or symbolic reference to the Trinity.

46. Is There a Secret Message in the Tablecloth?

- Some researchers argue that the patterns and folds in the tablecloth contain symbols or cryptic text, perhaps encoding messages.

47. Is There a Hidden Gospel in the Painting?

- Some speculate that the painting contains coded references to alternative or “lost” gospels, especially due to its unique portrayal of John and other symbolic elements.

48. Did Leonardo Paint His Own Beliefs About Jesus?

- The unusual details in the painting lead some to believe that Leonardo may have embedded his own beliefs about Jesus, possibly as a skeptic or a humanist.

49. Could It Be a Warning to Future Generations?

- The emotional expressions and intense energy in the painting lead some to interpret it as a warning or prophecy directed at future generations.

50. The Painting’s Connection to Divine Proportion

- Some mathematicians propose that the layout of figures and background in the painting reflects divine proportions, highlighting Leonardo’s knowledge of sacred geometry.

51. Why is the Painting at Santa Maria delle Grazie?

- Scholars question why Leonardo’s work was specifically commissioned for this convent, given his secular views and controversies.

52. Was Mary Magdalene Purposefully Excluded?

- Many theories suggest that Mary Magdalene may have been excluded from the scene, raising questions about her significance in Jesus’s life.

53. Why Are There So Many Different Facial Expressions?

- Leonardo took great care to depict each apostle’s unique expression, leading to interpretations that these facial nuances hold deeper spiritual messages.

54. The Curious Expression of Thomas

- Thomas points upward, a gesture that some believe symbolizes doubt or disbelief—a nod to his eventual doubt of the resurrection.

55. Is the Color Scheme Intentional?

- Leonardo’s use of color, particularly the blues and reds in Jesus’s attire, has sparked theories about whether he aimed to evoke emotions or allegorical meaning.

56. Does It Allude to the Philosopher’s Stone?

- Some alchemists suggest that the painting’s composition and elements might contain symbolic references to the Philosopher’s Stone, a legendary alchemical substance.

57. Could the Expressions Predict Future Conflicts?

- Art historians have examined whether the apostles’ expressions foreshadow the conflicts and persecution that early Christians would face.

58. Did Leonardo Encode Alchemical Symbols?

- The positioning of hands, food, and objects has led some researchers to argue that Leonardo embedded alchemical symbols, possibly alluding to transformation.

59. Is the Painting a Cipher for a Lost Language?

- Some theorists propose that the shapes and positions in The Last Supper could represent a cryptographic code or lost language.

60. Did Leonardo Create a Puzzle in the Painting?

- The enigmatic expressions, gestures, and positioning of objects have led some to speculate that Leonardo intended The Last Supper as a puzzle with hidden solutions.

61. Are There Hidden Celestial Symbols?

- The three windows and patterns behind Jesus have led some to interpret celestial symbols in the painting, possibly representing heaven or the cosmos.

62. The Role of the Disembodied Hand

- The hand holding a knife, disconnected from any body, has raised questions of hidden threats or divine judgment, especially as it points in the direction of Judas.

63. Is the Painting a Hidden Map?

- Some theorists believe that The Last Supper might contain a map—geographical or spiritual—that, when deciphered, reveals secret paths or meanings.

64. Does It Reflect Leonardo’s Study of Anatomy?

- Leonardo’s deep knowledge of anatomy is evident in the apostles’ lifelike expressions and gestures, but some wonder if the positioning of the apostles contains anatomical symbolism.

65. The Unique Depiction of Peter

- Peter’s gesture and stern expression have led some to theorize that Leonardo wanted to convey Peter’s loyalty, protection, or even hidden guilt.

66. A Scene Foreshadowing a Greater Revelation?

- Some believe the painting hints at an impending revelation beyond the Last Supper, alluding to the resurrection or an alternative spiritual truth.

67. Why Did Leonardo Use Tempera and Oil?

- The unconventional use of tempera and oil on dry plaster was unusual and caused issues with durability, leading some to wonder if he had a particular reason for choosing these materials.

68. Is the Table Symbolic of the World?

- The long table with figures on either side has been interpreted as representing the world, with Jesus symbolizing divine presence among humanity.

69. Is There a Coded Text in the Background?

- Some researchers argue that shapes in the background could contain letters or a cryptic text, possibly alluding to hidden messages.

70. Does Each Apostle’s Gesture Reveal Their Destiny?

- The unique hand gestures and expressions of each apostle have led some to interpret them as symbolic foreshadowing of their future roles or martyrdoms.

71. Why Did Leonardo Depict John So Young?

- John is traditionally depicted as youthful, but Leonardo’s emphasis on his youthfulness raises questions about whether he intended John to symbolize innocence.

72. Could There Be a Symbolic Connection to Leonardo’s Notebooks?

- Some argue that the painting contains concepts from Leonardo’s scientific notebooks, merging his scientific and spiritual ideas into this one masterpiece.

73. The Role of the Central Window Behind Jesus

- The central window behind Jesus is often interpreted as symbolizing divinity or enlightenment, possibly serving as a metaphor for heaven.

74. What Is Hidden in the Shadows?

- Shadows in the painting have been scrutinized, with some suggesting they contain hidden shapes or symbols, potentially alluding to a spiritual struggle.

75. Was It Meant to Contain a Secret Gospel?

- Some theorists propose that Leonardo may have encoded references to alternative gospels, challenging traditional interpretations of Christianity.

76. Is There a Link to the Divine Feminine?

- Interpretations argue that Leonardo may have hinted at the divine feminine, with certain figures, gestures, and arrangements seen as subtle references.

77. The Absence of Fish

- Given that fish were a common Christian symbol, their absence from the table raises questions about whether Leonardo omitted them intentionally or symbolically.

78. Did Leonardo’s Painting Method Hide Details?

- Leonardo’s choice to experiment with new painting methods led to damage, with some wondering if lost details might have contained important symbols or messages.

79. Could It Reflect a Hidden Star Map?

- Certain theorists suggest that the placement of the figures and objects might resemble a star map, possibly indicating astronomical knowledge.

80. The Hidden Meaning of the Light Source

- The diffuse lighting in the painting, unusual for Renaissance art, has led some to believe Leonardo intended the light to symbolize an otherworldly source or divine presence.