Part:-3

Investigation

A Joint Investigation Team (JIT) including experts from Malaysia, China, the United Kingdom, the United States, and France was promptly put together by Malaysia and led by “an independent investigator in charge” in compliance with ICAO guidelines. A medical and human aspects group, an operations group, and an airworthiness group made comprised the team.

The operations group was tasked with reviewing flight recorders, operations, and meteorology; the medical and human factors group was tasked with looking into psychological, pathological, and survival factors; and the airworthiness group was tasked with looking into issues pertaining to the aircraft’s maintenance records, structures, and systems.

On April 6, 2014, Malaysia also said that it had established three ministerial committees: one to coordinate the establishment of the JIT, one to oversee the Malaysian assets used in the hunt, and one to determine the Next of Kin. The Royal Malaysia Police spearheaded the criminal investigation, with support from Interpol and other pertinent foreign law enforcement agencies.

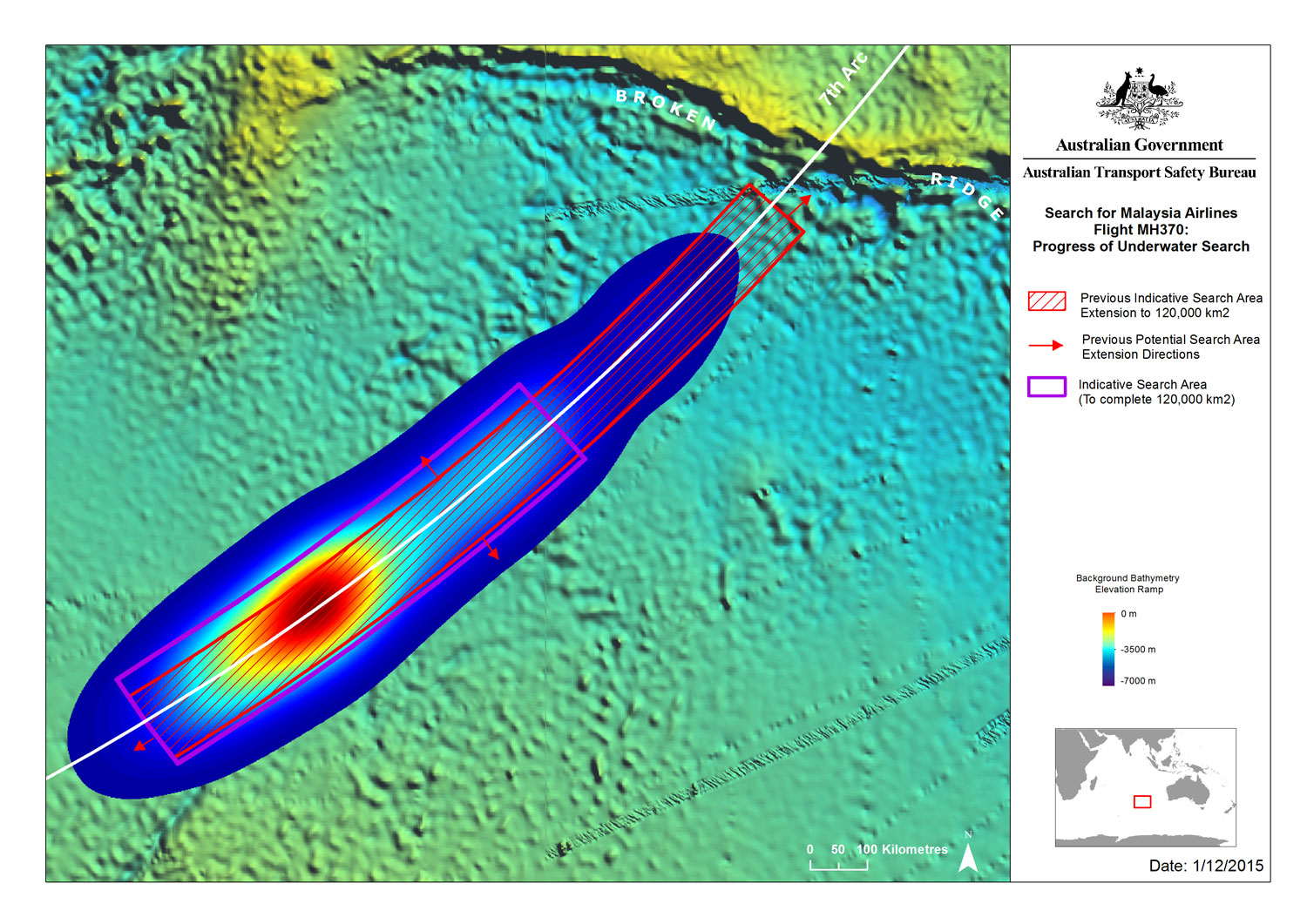

Australia assumed responsibility for organizing the search, rescue, and recovery efforts on March 17. The Joint Agency Coordination Centre (JACC) oversaw the search activities for the following six weeks while the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) and ATSB determined the search area by comparing data with the JIT and other governmental and scholarly sources.

The ATSB assumed responsibility for determining the search area after the fourth search phase. To ascertain the most likely location of the aircraft at the 00:19 UTC (08:19 MYT) satellite transmission, the ATSB formed a search plan working group in May.

Experts in airplanes and satellites from the Department of Civil Aviation (Malaysia), Boeing (US), Air Accidents Investigation Branch (UK), Thales (France), Inmarsat (UK), National Transportation Safety Board (US), and Defence Science and Technology Group (Australia) were part of the working group.

The only other nation carrying out the probe (via its Air Transport Gendarmerie) as of October 2018 was France, which aimed to confirm all of the technical data sent, including that supplied by Inmarsat.

Underwater hydrophone signals produced by aircraft crashes in the ocean were studied in 2024 by researchers at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom. According to the researchers, these signals may be crucial in identifying MH370’s last resting spot, which might reintroduce the UK into the hunt.

Interim and final reports

The dates of the two interim reports were March 8, 2015, and March 2016. They included accurate details on the aircraft, but no analysis. The 440-page final report from the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, which was released on October 3, 2017, recommended that aircraft be outfitted with more accurate flight monitoring equipment. On July 30, 2018, the 1,500-page final report from the Malaysian Ministry of Transportation was made public.

The jet was manually turned around, deviating from its regular flight course just after 1am, “either by the pilot or a third party,” according to the report. It was twenty minutes before anybody was notified that the plane was gone. Azharuddin Abdul Rahman, the Chairman of the Malaysian Civil Aviation Authority, resigned on July 31, 2018, in response to these reports of shortcomings in air traffic management.

Analysis of satellite communication

After Flight 370 vanished from Malaysian military radar at 02:22 MYT, the only important hints to its position are the communications between Flight 370 and the Inmarsat satellite communication network, which were relayed by the Inmarsat-3 F1 satellite.

Inferring potential in-flight incidents has also been done using these conversations. Without knowing the precise position, direction, or speed of the aircraft, the investigating team had to piece together Flight 370’s flight route from a small number of communications.

Technical background

Using the ACARS communications protocol, automatic data signals from onboard equipment and messages issued from the aircraft cockpit are transmitted via aeronautical satellite communication (SATCOM) systems. SATCOM can also be used to provide phone, fax, and data communications utilizing different protocols, as well as to transmit FANS and ATN messages.

To transmit and receive signals over the satellite communications network, the aircraft utilizes a satellite data unit (SDU); this functions separately from the other onboard systems that use SATCOM to connect, mostly using the ACARS protocol.

Before being relayed to a ground station, where it is processed and, if necessary, routed to its intended destination (such as Malaysia Airlines’ operations center), signals from the SDU are sent to a communications satellite, which amplifies and modifies their frequency. From the ground, the signals are sent back to the aircraft in reverse order.

When the SDU first turns on, it sends a log-on request to the Inmarsat network, which the ground station acknowledges in an effort to establish a connection. In addition to determining which satellite should be used to send messages to the SDU, this also helps to ascertain whether the SDU is owned by an active service subscriber.

After connecting, the ground station sends a “log-on interrogation” message, often known as a “ping,” to the data terminal (the SDU) if no more communication has been received from it for an hour. If the terminal is operational, it will immediately reply to the ping. A “handshake” is the word used to describe the complete process of questioning the terminal.

SDU communications

The SDU was still operational even though Flight 370’s ACARS data connection ceased working between 01:07 and 02:03 MYT, perhaps around the same time the aircraft lost contact with secondary radar. The following incidents were noted in the log of Inmarsat’s ground station in Perth, Western Australia, following the last main radar contact west of Malaysia (all timings are MYT/UTC+8):

- 02:25:27 – First handshake (“log-on request” initiated by aircraft)

- 02:39:52 – Ground to aircraft telephone call, acknowledged by SDU, unanswered

- 03:41:00 – Second handshake (initiated by ground station)

- 04:41:02 – Third handshake (initiated by ground station)

- 05:41:24 – Fourth handshake (initiated by ground station)

- 06:41:19 – Fifth handshake (initiated by ground station)

- 07:13:58 – Ground to aircraft telephone call, acknowledged by SDU, unanswered

- 08:10:58 – Sixth handshake (initiated by ground station)

- 08:19:29 – Seventh handshake (initiated by aircraft); widely reported as a “partial handshake'”, consisting of the following two transmissions:

- 08:19:29.416 – “log-on request” message transmitted by aircraft (seventh “partial” handshake)

- 08:19:37.443 – “log-on acknowledge” message transmitted by aircraft (last transmission received from Flight 370)

The aircraft did not respond to a ping at 09:15.

Inferences

The satellite communications allow for some deductions. First, seven hours after the last communication with air traffic control over the South China Sea, the aircraft continued to operate until at least 08:19 MYT. The airplane was traveling at a high speed, as shown by the fluctuating burst frequency offset (BFO) data.

It may also be assumed that the aircraft’s navigation system was functioning because the SDU requires position and track data to maintain its antenna pointing toward the satellite.

It may be inferred that the aircraft lost its capacity to connect with the ground station at some point between 08:19 and 09:15 because it did not reply to a ping at that time. There are only a few reasons why the SDU might send the “log-on request” log-on message that was sent from the aircraft at 08:19:29.

These include a power outage, software malfunction, the loss of vital systems that provide input to the SDU, or a connection loss brought on by the attitude of the aircraft. The most likely explanation, according to investigators, is that it was delivered during power-up following an electrical outage.

The satellite communication system remained out from a time following the last ACARS transmission at 01:06 until 02:25, presumably as a result of a power outage, according to the log-on request issued earlier in the flight at 02:25. The reason behind the satellite system’s restart at 02:25 after a period of inactivity is unknown, though.

Fuel exhaustion was likely since the aircraft had been in the air for 7 hours and 38 minutes at 08:19, compared to the usual 51⁄2 hour journey from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing. Some instruments and flying controls, including the SDU, would be powered by the aircraft’s ram air turbine (RAT) in the case of fuel exhaustion and engine flame-out, which would cut off power to the SDU.

The ground station log showed messages from the aircraft’s in-flight entertainment system around 90 seconds after the 02:25 handshake, which was also a log-on request. After the 08:19 handshake, similar messages should have been received, but none were, confirming the fuel-exhaustion theory.

Analysis

The research relied heavily on two factors related to these broadcasts that were noted in a log at the ground station:

- The time interval between sending a signal from the ground station and receiving a response is known as the burst time offset, or BTO. This metric, which includes the time the SDU spends between receiving and replying to the message and the time it takes for the ground station to analyze it, is proportionate to twice the distance between the ground station and the aircraft via the satellite. In order to define seven circles on the surface of the Earth, the points on whose circumference are equally spaced from the satellite at the determined distance, this metric was analyzed to determine the distance between the satellite and the airplane at the time of each of the seven handshakes. The portions of each circle that were out of the aircraft’s range were then removed, reducing those circles to arcs.

- The discrepancy between the predicted and received frequencies of broadcasts is known as burst frequency offset, or BFO. Doppler shifts during the signals’ journey from the aircraft to the satellite to the ground station, frequency translations at the satellite and ground station, a tiny, continuous error (bias) in the SDU due to drift and aging, and compensation used by the SDU to offset the Doppler shift on the uplink are the reasons for the discrepancy. Although several combinations of speed and direction might be legitimate answers, this metric was analyzed to establish the aircraft’s speed and heading.

Investigators created candidate pathways that were examined independently using two techniques by integrating the aircraft’s performance limits (such as fuel consumption, potential speeds, and altitudes) with the distance between the aircraft and the satellite, speed, and direction.

The first determined the BTO and BFO values along these routes and compared them with the values obtained from Flight 370. It was assumed that the aircraft was operating on one of the three autopilot modes (two are further impacted by whether the navigation system used magnetic north or true north as a reference).

To reduce the discrepancy between the calculated BFO of the path and the numbers obtained from Flight 370, the second technique produced pathways in which the aircraft’s speed and direction were modified at the moment of each handshake. 80% of the highest probability paths for both analyses combined intersect the BTO arc of the sixth handshake between 32.5°S and 38.1°S, which can be extrapolated to 33.5°S and 38.3°S along the BTO arc of the seventh handshake. A probability distribution for each method at the BTO arc of the sixth handshake of the two methods was then created and compared.

Analysis of hydrophone data

Cardiff University academics questioned the impact’s stated location and timing in a May 2024 Scientific Reports article. Dr. Usama Kadri said that, in contrast to the “clear pressure signals” shown in data from prior accidents with comparable impact, hydrophone data related to the crash of MH370 revealed “only a single, relatively weak signal” within the time period and area of the official search.

Additionally, he stated that “it is implausible to imagine that a significant crash of an aircraft on the ocean surface would fail to generate a discernible pressure signature,” implying that controlled explosion experiments could “almost pinpoint” the location of the aircraft or perhaps necessitate a reevaluation of the currently established time frame or location.

Speculated causes of disappearance

Murder/suicide by pilot

The pilots’ houses were examined by Malaysian authorities, who also confiscated the financial information of all 12 crew members. According to the preliminary assessment released by Malaysia in March 2015, an examination of the pilots’ CCTV footage revealed “no significant behavioural changes” and “no evidence of recent or imminent significant financial transactions carried out” by any of the crew members or pilots.

But according to US authorities, the most plausible theory is that someone in Flight 370’s cockpit changed the autopilot’s settings to steer the plane south across the Indian Ocean. According to media sources, Malaysian investigators have named Captain Zaharie as the main suspect in the event that Flight 370’s disappearance is ultimately linked to human interference.

In a 2020 Sky News program, Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who was in office when MH370 vanished, revealed: “My very clear understanding, from the very top levels of the Malaysian government, is that from very, very early on, they thought it was murder-suicide by the pilot.”

A retired British aviation engineer named Richard Godfrey made an untested idea that the aircraft’s flight route may be mapped by analyzing the interruption to Weak Signal Propagation Reporter (WSPR) signals on the day in question. This theory is congruent with the murder/suicide theory.

In November 2021, he said that his technology-based study showed the aircraft was placed in a holding pattern for approximately 22 minutes in a region 150 nautical miles off the Sumatra coast. In March 2024, it was announced that researchers at the University of Liverpool were conducting a significant new investigation to confirm the feasibility of the technology and its potential implications for aircraft location.

“I do not believe that historical data from the WSPR network can provide any information useful for aircraft tracking,” said Nobel Prize winner Joseph Hooton Taylor Jr., the man who created WSPR. “It’s absurd to think that historical WSPR data could be used to track the course of ill-fated flight MH370,” Taylor said in reference to the tragic flight. or any other trip of an airplane, for that matter.

Pilot’s flight simulator

An FBI analysis of the flight simulator’s computer hard drive revealed a route on Captain Zaharie’s home flight simulator that closely matched the projected flight over the Indian Ocean, according to a 2016 New York magazine article that cited a confidential document from the Malaysian police investigation. The FBI withheld this information from the publicly available investigative report. This is what New York wrote:

Less than a month before Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 disappeared under eerily similar circumstances, its captain, Zaharie Ahmad Shah, conducted a simulated flight deep into the remote southern Indian Ocean, according to a confidential document obtained by New York from the Malaysian police investigation into the plane’s disappearance. The greatest proof yet that Zaharie stole the jet in a planned mass murder-suicide is the revelation, which Malaysia omitted from a long public report on the probe.

[…] According to the recently made public documents, Malaysian authorities may have concealed at least one significant piece of damaging material. This is not wholly unexpected, given national safety boards have a history of rejecting the idea that their pilots could have purposefully wrecked a plane carrying passengers.

The ATSB verified the FBI’s conclusions on the flight simulation. The Malaysian authorities verified the simulation, but in a “nothing sinister” report.

Power interruption

Prior to responding with an acknowledgement message at 01:07 in response to a ground-to-air ACARS transmission, the SATCOM connection operated properly from pre-flight (starting at 0:00 MYT). The Satellite Data Unit (SDU) lost power somewhere between 01:07 and 02:03. The final assessment said “it is likely that the loss of communication prior to the diversion is due to the systems being manually turned off or power interrupted to them.”

Najib Razak, the prime minister of Malaysia, stated that it was evident that someone was attempting to conceal the plane’s position and direction by purposefully turning off the radar transponders and the flight data transmission system. The aircraft’s SDU made a log-on request and restarted itself at 02:25.

Passenger involvement

Every passenger listed on the manifest had their background examined by Malaysian and US agencies. For a brief while, a passenger who was employed as a flight engineer for a Swiss jet charter firm was suspected of being a possible hijacker due to his alleged “aviation skills.”

Following Flight 370’s disappearance, suspicion was aroused when it was discovered that two men had boarded the aircraft using passports that had been stolen. Within the previous two years, there had been reports of the theft of the Austrian and Italian passports in Thailand.

Later, it was discovered that the two travelers were Iranian males, one of whom was 19 years old and the other 29. They had used legitimate Iranian passports to enter Malaysia on February 28. The Interpol Secretary General subsequently said that the agency was “inclined to conclude that it was not a terrorist incident” and that they were thought to be asylum seekers.

The Chinese authorities declared on March 18 that it had screened every Chinese passenger on the plane and that no suspected involvement in “destruction or terror attacks” had been found.

Cargo

Malaysian investigators found that of the 10,806 kg (23,823 lb) of goods carried by Flight 370, two21 kilograms (487 lb) of lithium-ion batteries and four unit load devices (standardized cargo containers) of the tropical fruit mangosteens (totaling 4,566 kg (10,066 lb)) were of interest. Khalid Abu Bakar, the chief of Malaysian police, said that in order to rule out sabotage, the individuals who handled the mangosteens and the Chinese importers were questioned.

A shipment of 2,453 kg (5,408 lb) of lithium-ion batteries was being transported from Motorola Solutions’ facility in Bayan Lepas, Malaysia, to Tianjin, China. Lithium-ion batteries can cause severe fires if they overheat and ignite, which has happened on other flights and led to stringent regulations on transport aircraft.

Although they were packaged in compliance with IATA guidelines, they were not subjected to any additional inspections at Kuala Lumpur International Airport prior to being loaded onto Flight 370.

Unresponsive crew or hypoxia

According to an ATSB analysis, an unresponsive crew or hypoxia event “best fit the available evidence” for the five hours of Flight 370’s flight as it traveled south over the Indian Ocean without communication or significant deviations in its track, most likely on autopilot. The analysis compared the evidence available for Flight 370 with three categories of accidents: an in-flight upset (e.g., stall), a glide event (e.g., engine failure, fuel exhaustion), and an unresponsive crew or hypoxia event.

Investigators cannot agree on either the hypoxia or the unresponsive crew scenario. The aircraft would have probably gone into a spiral dive and into the water within 20 nmi (37 km; 23 mi) of the flameout and autopilot disengagement if no control inputs had been made after that.

The spiral dive at high speed theory was supported by the flaperon study, which revealed that the landing flaps were not extended. “We have quite a bit of data to tell us that the aircraft, if it was being controlled at the end, it wasn’t very successfully being controlled,” the ATSB’s spokeswoman said in May 2018, reaffirming the agency’s claim that the airplane was out of control when it crashed.

Aftermath

Malaysian officials’ early public statements on the disappearance of Flight 370 were riddled with ambiguity. With civilian authorities periodically opposing military commanders, the airline and the Malaysian government disseminated vague, partial, and occasionally erroneous information. For consistently disclosing conflicting information, particularly about the final position and time of communication with the aircraft, Malaysian officials came under fire.

Hishammuddin Hussein, Malaysia’s acting minister of transport and defense until May 2018, denied that there were any issues between the participating nations. However, scholars clarified that the search was being hampered by real trust issues in cooperation and intelligence sharing due to regional conflicts.

According to specialists in international relations, real multilateral cooperation was extremely challenging due to deeply ingrained rivalry over sovereignty, security, intelligence, and national interests.

According to a Chinese scholar, the search was not multilateral because the parties were conducting their own individual searches. The Vietnamese government’s approval of Chinese planes flying over its airspace was cited by the Guardian newspaper as a sign of good cooperation.

After Vietnam’s Deputy Transport Minister said that Malaysian officials had not spoken with them despite requests for more information, the nation temporarily reduced the scope of its search efforts. Days later, the Chinese Foreign Ministry reiterated China’s call for the Malaysian government to assume leadership and carry out the operation more transparently, which was made through the official Xinhua News Agency.

After first refusing to make raw data from its military radar public because it believed the material was “too sensitive,” Malaysia eventually agreed. According to defense experts, providing outsiders with access to radar data may be delicate from a military standpoint. For instance, “The rate at which they can take the picture can also reveal how good the radar system is.”

According to one theory, several nations may have already received radar data on the planes but were hesitant to divulge any information that may expose their defense capabilities and jeopardize their own security.

Similar to this, if a water impact occurs, submarines patrolling the South China Sea may have knowledge, and sharing that information might disclose the whereabouts and listening capabilities of those submarines.

The delay in the search attempts was also criticized. Three days after the plane vanished, on March 11, 2014, the British satellite company Inmarsat (or its partner, SITA) gave authorities information indicating that the plane was not in the vicinity of the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand regions under search at the time and might have changed its route via a southern or northern corridor. It wasn’t until the Malaysian Prime Minister made this information public during a news conference on March 15th.

Malaysia Airlines gave the explanation that the raw satellite signals needed to be checked and examined “so that their significance could be properly understood” before they could be publicly acknowledged, which is why information about them had not been made available earlier.

After receiving the Inmarsat data on March 12, Malaysian and US investigators reviewed it right away, according to Acting Transport Minister Hishammuddin. On two different occasions, they decided to transmit the data to the US for additional analysis. By the time the data analysis was finished on March 14, the AAIB had independently reached the same result.

Families of Flight 370 passengers launched an Indiegogo crowdfunding campaign in June 2014 with the aim of raising US$100,000 (approximately $128,704 in 2023) and eventually US$5 million as a reward to entice anyone who knew where Flight 370 was or what caused it to vanish to come forward. With 1,007 donors, the campaign raised US$100,516 before it concluded on August 8, 2014.

Malaysia Airlines

Ahmad Jauhari Yahya, the CEO of Malaysia Airlines, said that ticket sales had decreased a month following the disappearance, but he did not elaborate. This could have happened in part because the airline’s promotional activities were halted after the disappearance. The airline’s “primary focus…is that we do take care of the families in terms of their emotional needs and also their financial needs,” Ahmad said in a Wall Street Journal interview. It is crucial that we provide them answers. Additionally, it is crucial that the world has answers.

In other comments, Ahmad stated that the airline had sufficient insurance to cover the monetary loss resulting from the disappearance of Flight 370, but he was unsure of when the business might begin to restore its reputation. Malaysia Airlines had a 60% decrease in reservations in March in China, the country from which the majority of its passengers came.

Starting on March 14, 2014, Malaysia Airlines decommissioned the MH370 flight number and switched it to MH318 (Flight 318). Redesignating flights following infamous catastrophes is a standard process for airlines. As of October 2023, Malaysia Airlines continues to fly the MH318 route between Kuala Lumpur and Beijing, however it currently lands at Beijing Daxing instead of Beijing Capital.

In March 2014, Malaysia Airlines received US$110 million (about $193 million in 2023) from insurers to fund the search and early compensation to the families of the passengers. According to statements made in May by Allianz, the flight’s principal reinsurer, the insured market loss on Flight 370, including the search, was around US$350 million.

Malaysia Airlines declared in 2017 that it was the first airline to sign up for a new service that would use orbiting satellites to track its aircraft anywhere in the globe.

Financial troubles

Malaysia Airlines was having trouble reducing expenses to compete with a slew of new low-cost airlines in the area around the time of Flight 370’s disappearance. In 2013, 2012, and 2011, Malaysia Airlines recorded losses of RM1.17 billion (US$356 million), RM433 million, and RM2.5 billion, respectively.

The first quarter of 2014 saw Malaysia Airlines lose RM443.4 million (US$137.4 million) from January to March. RM307.04 million (US$97.6 million) was lost in the second quarter, the first full quarter following the disappearance of Flight 370. This was a 75% increase over losses in the second quarter of 2013.

Analysts in the industry predicted that Malaysia Airlines will continue to lose market share and encounter difficulties differentiating itself from rivals while resolving its financial difficulties. In contrast to the Malaysian stock market’s 80% increase over the same time period, the company’s shares had dropped 80% during the preceding five years, including by as much as 20% after Flight 370 vanished.

In order to generate a profit again, Malaysia Airlines would need to rebrand, fix its reputation, and get government support, according to a number of analysts and the media. The July loss of Flight 17 significantly worsened Malaysia Airline’s financial issues.

Due to the airline’s poor financial performance and the combined impact of the loss of Flight 370 and Flight 17 on consumer confidence, Khazanah Nasional, the majority shareholder (69.37%) and Malaysian state-run investment arm, announced on August 8 that it would buy the remaining airline shares, renationalizing the airline. On September 1, 2015, Malaysia Airlines underwent a renationalization.