Part:-1

Malaysia Airlines airplane 370 (MH370/MAS370) was an international passenger airplane that was scheduled to arrive at Beijing Capital International Airport in China from Kuala Lumpur International Airport in Malaysia when it vanished from radar on March 8, 2014. Its disappearance’s cause has not been identified. It is still the bloodiest example of aircraft disappearance and is considered by many to be the biggest enigma in aviation history.

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370

| Field | Value |

|---|---|

| Disappearance Date | 8 March 2014 |

| Summary | Inconclusive, some debris found |

| Site | Indian Ocean, most likely southern |

| Aircraft Type | Boeing 777-2H6ER |

| Operator | Malaysia Airlines |

| IATA Flight No. | MH370 |

| ICAO Flight No. | MAS370 |

| Call Sign | MALAYSIAN 370 |

| Registration | 9M-MRO |

| Flight Origin | Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia |

| Destination | Beijing Capital International Airport, Beijing, China |

| Occupants | 239 |

| Passengers | 227 |

| Crew | 12 |

| Fatalities | 239 (presumed) |

| Survivors | 0 (presumed) |

The Boeing 777-200ER, registered as 9M-MRO, was over the South China Sea when the crew last spoke with air traffic control (ATC) around 38 minutes after departure. Minutes after it vanished from ATC’s secondary monitoring radar screens, the Malaysian military’s primary radar system continued to follow the aircraft for an additional hour, despite it veering westward from its intended flight path and across the Andaman Sea and Malay Peninsula. 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) northwest of Penang Island in northwest Peninsular Malaysia, it was out of radar range.

Prior to being overtaken in all three categories by Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which was shot down by Russian-backed forces while flying over Ukraine four months later on July 17, 2014, the disappearance of Flight 370 was the deadliest incident involving a Boeing 777, the deadliest incident of 2014, and the deadliest in Malaysia Airlines’ history, with all 227 passengers and 12 crew members believed dead.

The hunt for the missing plane turned into the priciest aviation search ever. Before a new examination of the aircraft’s automatic transmissions with an Inmarsat satellite revealed that the jet had flown far southward across the southern Indian Ocean, it first concentrated on the South China Sea and Andaman Sea.

Given that the majority of the passengers on Flight 370 were of Chinese descent, the Chinese public, especially the relatives of the victims, strongly criticized the absence of official information in the days immediately following the disappearance. Numerous pieces of wreckage that were proven to have been from Flight 370 washed up on the coast in the western Indian Ocean in 2015 and 2016.

The operation’s Joint Agency Coordination Centre halted operations in January 2017 after a three-year search across 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) of ocean failed to find the plane. After six months, a second search conducted by private contractor Ocean Infinity in January 2018 was likewise unsuccessful.

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) first suggested that a hypoxia event was the most likely cause given the evidence available, primarily based on the analysis of data from the Inmarsat satellite with which the aircraft last communicated. However, investigators have not agreed on this theory.

At various stages of the investigation, possible hijacking scenarios were considered, including crew involvement, and suspicion of the airplane’s cargo manifest; many disappearance theories regarding the flight have also been reported by the media.

The final assessment released by the Malaysian Ministry of Transport in July 2018 was not conclusive. It brought to light Malaysian ATC’s unsuccessful attempts to get in touch with the plane soon after it vanished. Regulations and safety guidelines referencing Flight 370 have been put into place in the absence of a conclusive cause of disappearance in order to prevent a recurrence of the events surrounding the loss.

These include longer recording durations for flight data recorders and cockpit voice recorders, longer battery life for underwater locating beacons, and revised guidelines for reporting aircraft positions over open waters. China had contributed 10%, Australia 32%, and Malaysia 58% of the overall expenditure.

Timeline

Less than an hour after departure, at 01:19 MYT on March 8 (17:19 UTC on March 7), the Malaysia Airlines Boeing 777-200ER last spoke with ATC by voice. It was over the South China Sea. At 01:22 MYT, it vanished from ATC radar screens, but military radar continued to track it as it veered sharply to the west and crossed the Malay Peninsula, departing from its original northeastern course. It continued on this path until it was out of the military radar’s range at 02:22, over the Andaman Sea, 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) northwest of Penang Island in northwest Malaysia.

After the aircraft’s signal was last picked up by secondary surveillance radar in the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand, the multinational search effort for the aircraft—which would turn out to be the most costly aviation search in history—was quickly expanded to the Andaman Sea and the Strait of Malacca.

The flight continued until at least 08:19 (nearly an hour after Malaysia Airlines made the plane’s loss public) and flew south into the southern Indian Ocean, according to an analysis of satellite communications between the aircraft and Inmarsat’s satellite communications network, though the exact location is unknown. On March 17, as the search effort started to focus on the southern Indian Ocean, Australia took over the search.

The Malaysian authorities decided on March 24 that “Flight MH370 ended in the southern Indian Ocean” because the final position identified by the satellite communication was distant from any potential landing spots.

A thorough investigation of 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) of the sea bottom, located around 1,800 km (1,100 km; 970 nmi) southwest of Perth, Western Australia, between October 2016 and January 2017, found no signs of the aircraft. A number of pieces of marine debris that have been recovered off the coast of Africa and on islands in the Indian Ocean have been identified as being from Flight 370. The first piece was found on Réunion on July 29, 2015. There are several hypotheses regarding the aircraft’s disappearance because the majority of it has not been found.

The private US maritime exploration firm Ocean Infinity started searching in January 2018 in the area near 35.6°S 92.8°E, which was determined to be the most likely crash location based on the 2017 drift research. Malaysia has formed a Joint Investigation Team (JIT) to look into the occurrence in a prior search attempt, collaborating with specialists and authorities from foreign airlines. On October 17, 2017, Malaysia published its final report on Flight 370. Before the plane disappeared, neither the pilots nor the communication systems on board sent a distress signal, warnings of inclement weather, or mechanical issues. After an investigation, two travelers using stolen passports were ruled out as suspects.

After excluding everyone else from the flight of suspicion about potential reasons, Malaysian authorities named the captain as the main suspect if human action was the cause of the disappearance. Sometime between 01:07 and 02:03, the aircraft’s satellite data unit (SDU) lost power; three minutes after the aircraft had departed radar range, at 02:25, the SDU logged onto Inmarsat’s satellite communication network. The aircraft was assumed to have flown for six hours with minimal change in its course, ending when its fuel ran out, after turning south after passing north of Sumatra, according to a study of the satellite communications.

Flight 370, which claimed the lives of all 239 people on board, is the second-deadliest event in Malaysia Airlines’ history and the second-deadliest incident using a Boeing 777, after Flight 17 in both categories. By the end of 2014, Malaysia Airlines had been renationalized due to financial difficulties that were made worse by a decline in ticket sales following the downing of Flight 17 and the missing of Flight 370. China in particular harshly criticized the Malaysian authorities for its tardiness in disclosing information in the initial weeks of the hunt.

The limitations of aircraft tracking and flight recorders, such as the short battery life of underwater locator beacons (a problem that had been brought up approximately four years prior after the loss of Air France Flight 447, but had never been fixed), were made public by the disappearance of Flight 370. The International Civil Aviation Organization responded to the disappearance of Flight 370 by establishing new guidelines for reporting aircraft positions over open ocean, extending the time that cockpit voice recorders could record, and requiring new aircraft designs to have a way to recover the flight recorders and the data they contain before they sink into the ocean. These regulations went into effect in 2020.

Aircraft

A Boeing 777-2H6ER with serial number 28420 and registration 9M-MRO was used to operate Flight 370. Malaysia Airlines received the aircraft brand-new on May 31, 2002. Two Rolls-Royce Trent 892 engines propelled the aircraft, which could accommodate a maximum of 282 people. Despite a minor incident that resulted in a fractured wing tip during taxiing at Shanghai Pudong International Airport in August 2012, it had collected 53,471.6 hours and 7,526 cycles (takeoffs and landings) in service and had not been involved in any serious problems before.

The previous “A check” maintenance was performed on February 23, 2014. The airframe and engines of the aircraft complied with all relevant Airworthiness Directives. As part of standard maintenance, the crew member oxygen system was refilled on March 7, 2014; an analysis of this operation revealed nothing out of the ordinary. Leaked records, however, have shown that MH370 received additional fuel and oxygen supplies for crew members just before takeoff, ten years after the plane went missing.

The Boeing 777, a reliable and efficient aircraft, has generally enjoyed a strong safety record. However, like any complex machine, it has been involved in a few tragic accidents. These incidents, while unfortunate, are relatively rare considering the vast number of flights the 777 has operated. It’s important to note that each accident has its own unique set of circumstances and factors, and thorough investigations are conducted to identify the causes and implement measures to prevent future occurrences.

Passengers and crew

There were 227 people from 14 different countries on board, including 12 Malaysian staff members. Based on the flight manifest, Malaysia Airlines disclosed the names and nationalities of the passengers and crew on the day of the disappearance. Later, two Iranian travelers using stolen Italian and Austrian passports were added to the passenger list.

Sure!

| Nationality | Count |

|---|---|

| Australia | 6 |

| Canada | 2 |

| China | 153 |

| France | 4 |

| India | 5 |

| Indonesia | 7 |

| Iran | 2 |

| Malaysia | 50 |

| Netherlands | 1 |

| New Zealand | 2 |

| Russia | 1 |

| Taiwan | 1 |

| Ukraine | 2 |

| United States | 3 |

| Total (14 Nationalities) | 239 |

Crew

Ten cabin crew members and two pilots made up the 12 crew, all of them were Malaysian nationals.

- Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah, a 52-year-old Penang native, was the pilot in command. After training and obtaining his commercial pilot’s license, he joined Malaysia Airlines as a cadet pilot in 1981 and rose to the rank of second officer in 1983. In 1991, 1996, and 1998, he was elevated to captain of the Boeing 737-400, Airbus A330-300, and Boeing 777-200 aircraft, respectively. Since 2007, he has been a type-rating examiner and instructor. Zaharie’s flying experience totaled 18,365 hours.

- Fariq Abdul Hamid, a 26-year-old First Officer, was the co-pilot. He began his career with Malaysia Airlines in 2007 as a cadet pilot. He advanced to second officer of Boeing 737-400 aircraft in 2010, then first officer of the Boeing 737-400 in 2010, before switching to the Airbus A330-300 in 2012. He started training as a Boeing 777-200 first officer in November 2013. He was to be evaluated on his subsequent trip, which was trip 370, his last training flight. The total number of hours Fariq had flown was 2,763.

Passengers

Of the 227 passengers, 38 were Malaysian, and 153 were Chinese, including a group of 19 artists who were returning from a calligraphy exhibition in Kuala Lumpur with six family members and four workers. Twelve different nations made up the remaining passengers. Twenty passengers were Freescale Semiconductor personnel, twelve of them were from Malaysia and eight from China.

Tzu Chi, a worldwide Buddhist organization, promptly dispatched highly trained personnel to Beijing and Malaysia to provide emotional support to passengers’ families under a 2007 agreement with Malaysia Airlines.

Along with sending its own team of volunteers and caretakers, the airline also committed to pay for the transportation of the passengers’ families to Kuala Lumpur as well as their lodging, medical attention, and counseling. A total of 115 Chinese travelers’ relatives took flights to Kuala Lumpur. Fearing they would feel too alone in Malaysia, several other family members decided to stay in China.

Flight and disappearance

Early on Saturday, March 8, 2014, Flight 370 was due to depart Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, for Beijing, China. From its hub at Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA), Malaysia Airlines operates two daily flights to Beijing Capital International Airport. The flights are scheduled to depart at 00:35 local time (MYT; UTC+08:00) and arrive at 06:30 local time (CST; UTC+08:00). Two pilots, ten cabin crew members, 227 passengers, and 14,296 kg (31,517 lb) of freight were all on board.

With a projected flight time of 5 hours and 34 minutes, an estimated 37,200 kg (82,000 lb) of jet fuel would be used. The aircraft had a 7-hour, 31-minute endurance due to its 49,100 kilograms (108,200 lb) of fuel, including reserves. The additional gasoline was sufficient to switch to other airports, which would take 4,800 kg (10,600 lb) or 10,700 kg (23,600 lb) to get from Beijing to Jinan Yaoqiang International Airport and Hangzhou Xiaoshan International Airport, respectively.

Departure

After taking off from runway 32R at 00:42 MYT, air traffic control (ATC) gave the go-ahead for Flight 370 to climb to flight level 180g, or around 18,000 feet (5,500 m), on a direct route to navigational waypoint IGARI, which is situated at 6°56′12″N 103°35′6″E. According to voice analysis, the captain spoke with ATC after takeoff, and the first officer spoke with ATC when the aircraft was on the ground. The flight was moved from the airport’s ATC to “Lumpur Radar” air traffic control on frequency 132.6 MHz shortly after takeoff.

The Kuala Lumpur Area Control Centre (ACC) provides ATC across the Malaysian peninsula and nearby waterways; the frequency used for en route aviation traffic is called Lumpur Radar. Lumpur Radar approved flying 370 to flying level 350g, or around 35,000 feet (10,700 meters), at 00:46. The crew of flying 370 informed Lumpur Radar that they had arrived at flying level 350 at 01:01, and they reaffirmed this at 01:08.

Communication lost

At 01:06 MYT, the aircraft issued an automatic location report using the Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) protocol, which was its last signal before it vanished from radar. This communication included information about the total amount of fuel left, which was 43,800 kg (96,600 lb). At 01:19:30, Captain Zaharie accepted a change from Lumpur Radar to Ho Chi Minh ACC, which was the final verbal cue to air traffic control:

Lumpur Radar: “Contact Ho Chi Minh City at one two zero decimal nine, Malaysian three seven zero.” Good night.

“Good night,” said Flight 370. Three seven zero in Malaysia.

As the plane entered Vietnamese airspace, just north of the communication loss location, the crew was supposed to alert ATC in Ho Chi Minh City. Shortly after 01:30, the captain of another aircraft tried to use the international air distress frequency to reach the crew of Flight 370 in order to relay the request from Vietnamese air traffic control for the crew to get in touch with them. The captain claimed to have succeeded in establishing communication, but all he could hear was static and “mumbling.” Flight 370’s satellite data unit recognized calls to the cockpit at 02:39 and 07:13, but no one replied.

Radar

The Mode-S sign vanished from radar screens five seconds after Flight 370 was detected on radar at the Kuala Lumpur ACC at 01:20:31 MYT when it crossed the navigational waypoint IGARI (6°56′12″N 103°35′6″E) in the Gulf of Thailand.2. Flight 370 vanished from the Kuala Lumpur ACC radar screen at 01:21:13, and it was also lost on the Ho Chi Minh ACC radar at around the same time.

The Ho Chi Minh ACC radar indicated that the aircraft was at the nearby waypoint BITOD. The ADS-B transponder on Flight 370 stopped working after 01:21 because air traffic control employs secondary radar, which depends on a signal sent by a transponder on each aircraft.

The aircraft was flying at its designated cruising altitude of flight level 350g, according to the final transponder data, and its real airspeed was 471 knots (872 km/h; 542 mph). There was no rain or lightning in the area, and there were not many clouds. Subsequent investigation revealed that when Flight 370 vanished from secondary radar, it had 41,500 kg (91,500 lb) of fuel.

The Malaysian military’s main radar at the time the transponder failed showed Flight 370 moving right before starting a left turn toward the southwest. Military radar recorded Flight 370 at 35,700 feet (10,900 meters) on a 231° magnetic heading at 496 knots (919 km/h; 571 mph) between 01:30:35 and 01:35. As it resumed its journey across the Malay Peninsula, Flight 370’s altitude varied from 31,000 to 33,000 feet (9,400 to 10,100 meters).

Between 01:30:37 and 01:52:35, four unidentified aircraft were detected by a civilian main radar at Sultan Ismail Petra Airport, which has a 60 nmi (110 km; 69 mi) range. The unidentified aircraft’s tracks are “consistent with those of the military data.” 3–4 It was discovered that Flight 370 was just south of the island of Penang at 01:52. The aircraft then crossed the Strait of Malacca, passing near the waypoint VAMPI and Pulau Perak at 02:03. It then proceeded to waypoints MEKAR, NILAM, and probably IGOGU via air route N571.

At 02:22, 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi) after passing waypoint MEKAR: 3, 7 (which is 237 nmi (439 km; 273 mi) from Penang) and 247.3 nmi (458.0 km; 284.6 mi) northwest of Penang airport at an altitude of 29,500 ft (9,000 m), the last known radar detection was made from a point close to the boundaries of Malaysian military radar.

Because it was sensitive to disclose their capabilities, nations were hesitant to make information gathered by military radar public. Despite the fact that Flight 370 may have flown over or close to the northern point of Sumatra, Indonesia’s early-warning radar system failed to detect any aircraft using the transponder code. Before the transponder is believed to have been switched off, Indonesian military radar followed Flight 370 on its journey to waypoint IGARI. However, it did not specify if it was spotted later.

Prior to the transponder malfunctioning, Flight 370 was also picked up on radar in Vietnam and Thailand. Once the transponder is believed to have been switched off, the radar location signals for the code used by Flight 370 disappeared. Pham Quy Tieu, Vietnam’s deputy minister of transportation, said that on March 8, Vietnam had observed MH370 heading back west and that its operators had notified Malaysian authorities twice on the same day.

Although it is unknown when the final radar contact was established and the transmission lacked identifying information, Thai military radar picked up what may have been Flight 370. Additionally, Australia’s long-range JORN over-the-horizon radar system, which has a stated range of 3,000 km (1,900 mi), and its conventional system failed to identify the aircraft; the latter was not operational on the night of the disappearance.

Satellite communication resumes

The aircraft’s satellite communication system went down (maybe as a result of a power outage) sometime after the last ACARS message at 01:06 and stayed offline during the plane’s first detour from its intended flight route. A “log-on request” message, the first since the ACARS transmission at 01:06, was sent by the aircraft’s satellite communication system at 02:25 MYT for an unspecified reason.

The satellite then relayed the message to a ground station, which is run by the satellite telecommunications company Inmarsat. After connecting to the network, the aircraft’s satellite data unit answered two ground-to-aircraft phone calls at 02:39 and 07:13, none of which was answered by the pilot, and hourly status queries from Inmarsat for the following six hours.

The aircraft’s satellite communication system went down (maybe as a result of a power outage) sometime after the last ACARS message at 01:06 and stayed offline during the plane’s first detour from its intended flight route. A “log-on request” message, the first since the ACARS transmission at 01:06, was sent by the aircraft’s satellite communication system at 02:25 MYT for an unspecified reason.

The satellite then relayed the message to a ground station, which is run by the satellite telecommunications company Inmarsat. After connecting to the network, the aircraft’s satellite data unit answered two ground-to-aircraft phone calls at 02:39 and 07:13, none of which was answered by the pilot, and hourly status queries from Inmarsat for the following six hours.

Although the precise timing and location of the disaster are still unknown, investigators generally agree that Flight 370 fell somewhere in the southern Indian Ocean on March 8 between 08:19 and 09:15 as a result of fuel depletion.

Response by air traffic control

Inquiring about the location of Flight 370, which was last spotted by radar at waypoint BITOD, Ho Chi Minh Area Control Centre (ACC) called Kuala Lumpur Area Control Centre at 01:38 MYT. ACC advised Kuala Lumpur that it had not verbally communicated with Flight 370. Over the following 20 minutes, the two centers spoke on the phone four more times without providing any new information.

At 02:03, Kuala Lumpur ACC informed Ho Chi Minh ACC that Flight 370 was in Cambodian airspace, based on information from Malaysia Airlines’ operations center. In the next eight minutes, Ho Chi Minh ACC made two calls to Kuala Lumpur ACC to confirm that Flight 370 was in Cambodian airspace. When the Kuala Lumpur ACC watch supervisor contacted Malaysia Airlines’ operations center at 02:15, the airline responded that it could communicate with Flight 370 and that Flight 370 was in Cambodian airspace.

To find out if Flight 370’s intended flight route went through Cambodian airspace, Kuala Lumpur ACC got in touch with Ho Chi Minh ACC. According to Ho Chi Minh ACC, Flight 370 was not authorized to enter Cambodian airspace, and they had previously been in touch with Phnom Penh ACC, which is in charge of Cambodian airspace, but they were unable to get in touch with Flight 370.

When Kuala Lumpur ACC called Malaysia Airlines’ operations center at 02:34 to inquire about the status of communication with Flight 370, they were told that, according to a signal download, Flight 370 was in normal condition and was situated at 14°54′N 109°15′E. At the request of Ho Chi Minh ACC, a second Malaysia Airlines aircraft (Flight 386 headed for Shanghai) later tried to reach Flight 370 using emergency frequencies and the Lumpur Radar frequency, which is the frequency on which Flight 370 last spoke with Malaysian air traffic control. It didn’t work out.

Kuala Lumpur ACC was notified at 3:30 by Malaysia Airlines’ operations center that the previously reported positions were “based on flight projection and not reliable for aircraft positioning.” Kuala Lumpur ACC called Ho Chi Minh ACC during the course of the following hour to inquire as to whether they had alerted Chinese air traffic control. Information on Flight 370 was requested from Singapore ACC at 05:09. When an unnamed official called Kuala Lumpur ACC at 5:20 to inquire on Flight 370, he stated that, according to the information available, “MH370 never left Malaysian airspace.”

At 05:30, over four hours after communication with Flight 370 was lost, the Kuala Lumpur ACC watch supervisor activated the Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre (ARCC). When an aircraft is lost, search and rescue operations are coordinated by the ARCC, a command post located at an Area Control Center.

Assumed loss

At 07:24 MYT on March 8, one hour after the aircraft was supposed to arrive in Beijing, Malaysia Airlines released a media statement announcing that the government had started search and rescue efforts after Malaysian ATC lost contact with the jet at 02:40. Investigators and Malaysia Airlines were unaware that Flight 370 was still in the air at the time of this initial media statement. Search and rescue efforts were initiated while the plane was still flying over the Indian Ocean, although they initially concentrated on the South China Sea rather than the Indian Ocean, where Flight 370 is thought to have crashed.

Later, the time when communication was lost was changed to 01:21. Before the aircraft disappeared from radar screens, neither the pilots nor the aircraft’s communication systems transmitted a distress signal, warnings of inclement weather, or mechanical issues.

When Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak addressed the media on March 24 at 22:00 local time, he revealed that the Air Accidents Investigation Branch had informed him that it and satellite data provider Inmarsat had determined that the airliner’s final location before it vanished was in the southern Indian Ocean. The plane must have crashed into the water because there are no areas where it could have landed.

The relatives of Flight 370 passengers were summoned to an emergency conference in Beijing just prior to Najib’s speech at 22:00 MYT. Malaysia Airlines declared that there were no survivors and that Flight 370 was presumed lost. Most of the families were informed in person or over the phone, and others got an SMS (in Chinese and English) telling them that the plane probably crashed and there were no survivors.

According to the Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation, Flight 370’s status will be changed to “accident” on January 29, 2015, and all passengers and crew are presumed dead, according to a statement made by Azharuddin Abdul Rahman, director general of the Department of Civil Aviation Malaysia.

According to official estimates, Flight 370 was the deadliest aviation incident in Malaysian Airlines’ history at the time of its disappearance, more deadly than the 1977 hijacking and crash of Malaysian Airline System Flight 653, which killed all 100 passengers and crew, and the deadliest involving a Boeing 777, more deadly than Asiana Airlines Flight 214 (three fatalities). In each of those categories, Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, a Boeing 777-200ER that was shot down on July 17, 2014, killing all 298 persons on board, overtook Flight 370 131 days later.

Reported sightings

Several sightings of an aircraft that matched the specifications of the missing Boeing 777 were reported by the news media. For instance, CNN claimed on March 19, 2014, that the missing airplane was spotted by witnesses who included fisherman, an oil rig worker, and residents of the Maldives’ Kuda Huvadhoo atoll.

The Vietnamese authorities sent a search and rescue team after an oil-rig worker 186 miles (299 km) southeast of Vung Tau reported seeing a “burning object” in the sky that morning, an Indonesian fisherman reported seeing an aircraft crash near the Malacca Straits, and a fisherman reported seeing an unusually low-flying aircraft off the coast of Kota Bharu.

Three months later, a British woman reportedly saw an airplane burning while sailing in the Indian Ocean, according to the Phuket Gazette.

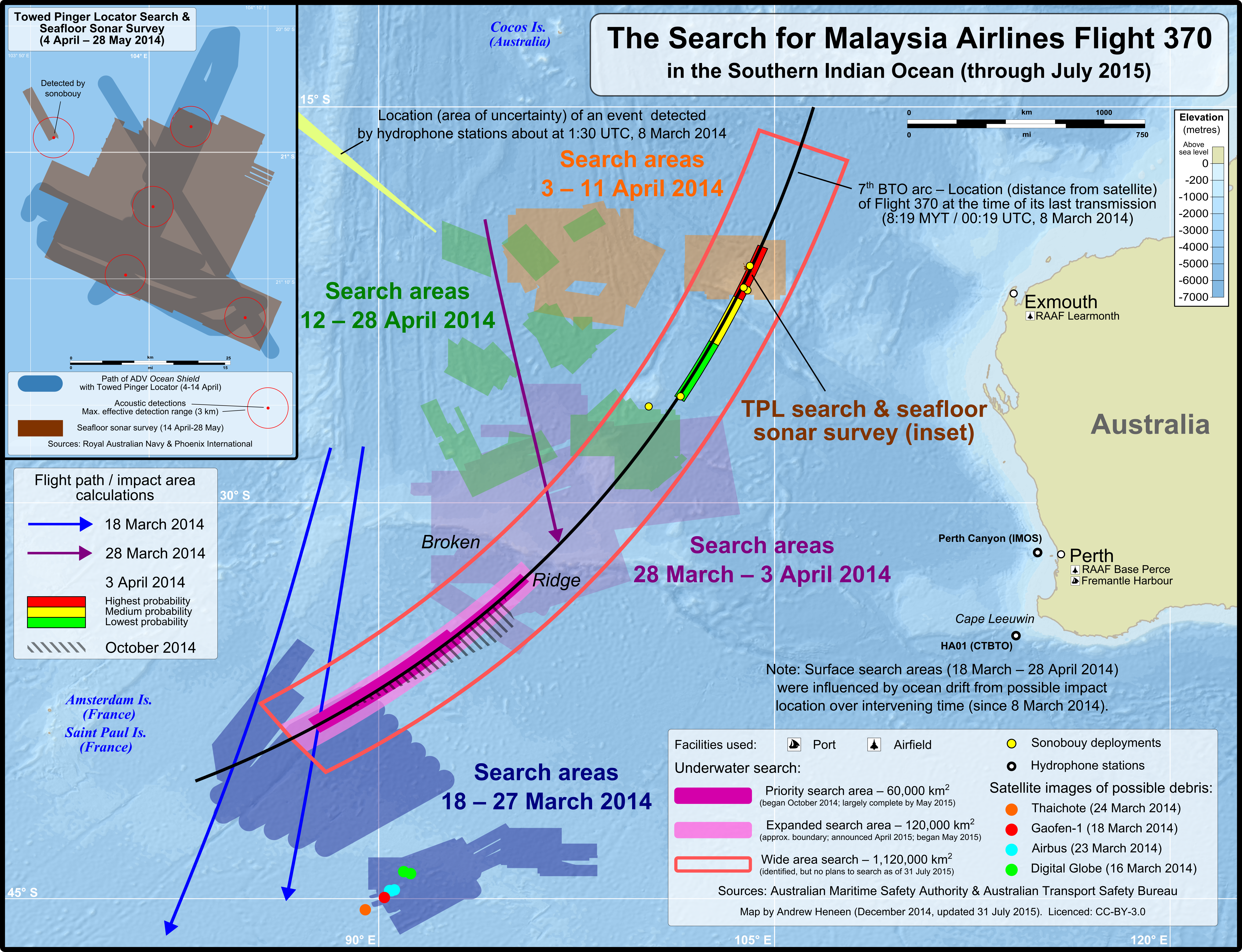

Search

Shortly after Flight 370 vanished, a search and rescue operation was initiated across southeast Asia. One week after the aircraft vanished, the surface search was shifted to the southern Indian Ocean after the first analysis of communications between the aircraft and a satellite. Over 4,600,000 km2 (1,800,000 sq mi) were searched by 19 boats and 345 military aircraft missions between March 18 and April 28. Around 1,800 kilometers (970 nmi; 1,100 mi) southwest of Perth, Western Australia, the search concluded with a bathymetric scan and sonar search of the sea bottom.

Beginning on March 30, 2014, the search was led by the Joint Agency Coordination Centre (JACC), an Australian government organization that was created especially to oversee the search and recovery of Flight 370. The search mainly involved the governments of Malaysia, China, and Australia.

After finding just some maritime debris off the African coast, the official search for Flight 370—which had turned out to be the most costly search operation in aviation history—was halted on January 17, 2017. As of June 30, 2017, the undersea search for the aircraft had cost US$155 million (~$190 million in 2023), according to the final ATSB report, which was released on October 17, 2017. Of this, 86% came from the undersea search, 10% from bathymetry, and 4% from program management.

China had contributed 10%, Australia 32%, and Malaysia 58% of the overall expenditure. Using satellite imagery and debris drift studies, the investigation also came to the conclusion that the region where the aircraft went down had been reduced to 25,000 km2 (9,700 sq mi).

Using the Norwegian ship Seabed Constructor, the private American maritime exploration firm Ocean Infinity recommenced the hunt for MH370 in the 25,000 km2 region in January 2018. Throughout the search, the search area was further expanded, and by the end of May 2018, the ship had used eight autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) to search an area of about 112,000 km2 (43,000 sq mi). Shortly later, the contract with the Malaysian government expired, and on June 9, 2018, the search was halted without finding anything.

Southeast Asia

Four hours after contact with the aircraft was lost, at 05:30 MYT, the Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre (ARCC) was established to coordinate search and rescue activities. The South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand were the first places searched. The search area was extended to cover a portion of the Strait of Malacca after Malaysian officials claimed that radar data suggested Flight 370 could have circled before disappearing from radar screens on the second day of the hunt.

Search operations were subsequently expanded in the Andaman Sea and Bay of Bengal after the chief of the Royal Malaysian Air Force announced on March 12 that an unidentified aircraft, thought to be Flight 370, had crossed the Malay peninsula and was last seen on military radar 370 km (200 nmi; 230 mi) northwest of the island of Penang.

The jet had been in the air for about six hours after it was last seen on Malaysian military radar, according to records of signals exchanged between the aircraft and a communications satellite over the Indian Ocean. Flight 370 was on one of two arcs, equally spaced from the satellite, when its final signal was made, according to preliminary analysis of these transmissions. Authorities declared on March 15, the day the research was made public, that they would stop searching the South China Sea, Gulf of Thailand, and Strait of Malacca in order to concentrate their efforts on the two routes.

Since the plane would have needed to fly through highly militarized territory, the northern arc—from northern Thailand to Kazakhstan—was quickly ruled out. The nations maintained that their military radar would have picked up an unidentified aircraft entering their area.

Southern Indian Ocean

The search’s focus was moved to the southern Indian Ocean west of Australia, as well as to Australia’s maritime and aviation Search and Rescue areas, which reach up to 75°F longitude. Australia therefore consented to oversee the search in the southern locus, which stretches from Sumatra to the southern Indian Ocean, on March 17.

To Be Continued in the next part