Introduction

East Asian landlocked Mongolia is bounded to the north and south by China and Russia. With 3.5 million people living in an area of 1,564,116 square kilometers (603,909 square miles), it is the world’s most sparsely inhabited sovereign state. With the Gobi Desert to the south and mountains to the west, Mongolia is the biggest landlocked nation without a sea border in the world. The majority of its territory is covered in grassland steppe. Over half of the nation’s population resides in Ulaanbaatar, the capital and largest city.

Numerous nomadic empires, such as the Xiongnu, Xianbei, Rouran, First Turkic Khaganate, Second Turkic Khaganate, Uyghur Khaganate, and others, have reigned over the region that is now Mongolia. The Mongol Empire, established by Genghis Khan in 1206, grew to be the most contiguous land empire in recorded history. Kublai Khan, his grandson, overthrew the Chinese mainland and founded the Yuan dynasty. With the exception of the time under Dayan Khan and Tumen Zasagt Khan, the Mongols withdrew to Mongolia with the fall of the Yuan and renewed their previous pattern of factional warfare.

The Manchu-founded Qing dynasty, which ruled Mongolia until the 17th century, had a major role in the growth of Tibetan Buddhism in that nation beginning in the 16th century. Buddhist monks made up about one-third of the adult male population by the early 20th century. Following the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, Mongolia proclaimed its independence from the Republic of China, which it finally attained in 1921.

The nation quickly joined the Soviet Union as a satellite state. The Mongolian People’s Republic was established as a socialist nation in 1924. Early in 1990, Mongolia underwent a peaceful democratic revolution in response to the anti-communist uprisings of 1989. As a result, there is now a multi-party system, a market economy, and a new constitution from 1992.

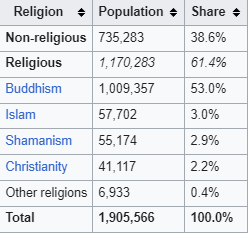

Nomadic or semi-nomadic people make up around 30% of the population, yet horse culture is still very important. The dominant religion is Buddhism (51.7%), followed by the nonreligious (40.6%) minority. Among ethnic Kazakhs, Islam is the third most common religious identity (3.2%). Kazakhs, Tuvans, and other ethnic minorities make up around 5% of the population, with the bulk of people being ethnic Mongols.

These ethnicities are mostly found in the western districts. Mongolia is a worldwide partner of NATO and a member of the Non-Aligned Movement, the Asia Cooperation Dialogue, the G77, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. In 1997, Mongolia became a member of the World Trade Organization and aimed to increase its involvement in trade and economic associations within the area.

Meaning and Origin

Latin for “Land of the Mongols” is how Mongolia is named. The origin of the Mongolian word “Mongol” (мoнгол) is unclear. It has been suggested that it is the name of a mountain or river; that it is a corruption of the Mongolian Mongkhe-tengri-gal (“Eternal Sky Fire”); or that it is derived from Mugulü, the founder of the Rouran Khaganate in the fourth century, who is first known as the “Mungu” (Chinese: 钙兀, Modern Chinese Měngwù, Middle Chinese Muwngu), a branch of the Shiwei in a list of northern tribes in the Tang dynasty in the eighth century, likely connected to the Mungku (Chinese: 蒙古, Modern Chinese Měnggɐ, Middle Chinese MuwngkuX).

The Khamag Mongols rose to prominence on the Mongolian Plateau following the collapse of the Liao Dynasty in 1125. But their battles with the Tatar Confederation and the Jin dynasty, who reigned over the Jurchens, had worn them down. Yeügei was the final leader of the tribe; his son Temüjin eventually brought the Shiwei tribes together to become the Mongol Empire (Yekhe Monggol Ulus). The name “Mongol” came to refer to a broad collection of Mongol-speaking tribes that were unified under Genghis Khan’s authority in the thirteenth century.

The official name of the state is “Mongolia” (Mongol Uls), having been adopted on February 13, 1992, with the approval of the new Constitution of Mongolia.

Past Events

Ancient times and prehistory

The Khoit Tsenkher Cave in Khovd Province is known as “the Lascaux of Mongolia” because of its vivid 20,000-year-old paintings of mammoths, lynx, Bactrian camels, and ostriches in shades of pink, brown, and red ochre. The Venus figurines from Mal’ta, which is now in Russia, date back 21,000 years and attest to the caliber of Upper Paleolithic art in northern Mongolia. Neolithic agricultural communities, such as those at Norovlin, Tamsagbulag, Bayanzag, and Rashaan Khad, date back to a time when horse-riding nomadism was introduced and became the dominant civilization in Mongolia’s history.

Archaeological evidence from the Copper and Bronze Age Afanasevo civilization (3500–2500 BC), an Indo-European society that flourished up to the Khangai Mountains in Central Mongolia, has revealed horse-riding nomadism in Mongolia. The wheeled vehicles discovered in the Afanasevan tombs have been determined to be older than 2200 BC. With the subsequent Okunev culture (2nd millennium BC), Andronovo culture (2300–1000 BC), and Karasuk culture (1500–300 BC), pastoral nomadism and metallurgy advanced, reaching a pinnacle with the Iron Age Xiongnu Empire in 209 BC. Pre-Xiongnu Bronze Age monuments include rock art, keregsur kurgans, deer stones, and square slab burials.

Agricultural production has been going on since the Neolithic era, although it has always been on a far smaller scale than pastoral nomadism. It’s possible that agriculture initially arrived from the West or developed locally on its own. In the east of what is now Mongolia, the Copper Age population has been classified as mongoloid, while in the west, as europoid. During the Bronze Age, Tocharians (Yuezhi) and Scythians lived in western Mongolia. The mummy of a 30- to 40-year-old man with blond hair, thought to be a Scythian warrior, was discovered in the Altai, Mongolia, and is thought to be around 2,500 years old.

The political center of the Eurasian Steppe moved to Mongolia with the introduction of horse nomadism, and it stayed there until the 18th century CE. The period of nomadic empires was foreshadowed by the incursions of northern pastoralists (such as the Guifang, Shanrong, and Donghu) into China during the Shang and Zhou dynasties (1600–1046 BC and 1046–256 BC, respectively).

Early states

Nomads have lived in Mongolia since prehistoric times, and occasionally they established large confederations that gained fame and power. The imperial army (Keshig), the office of the Khan, the Kurultai (Supreme Council), the left and right wings, and the decimal military system were common institutions. In 209 BC, Modu Shanyu united the Xiongnu, who belonged to an unidentified ethnic group, to create a confederation, which was the first of these empires. They quickly became the Qin Dynasty’s biggest danger, which compelled it to build the Great Wall of China. During Marshal Meng Tian’s reign, it was defended against the catastrophic Xiongnu incursions by up to about 300,000 men.

The Mongolic Xianbei dynasty (93–234 AD), which also controlled over most of modern-day Mongolia, succeeded the enormous Xiongnu kingdom (209 BC–93 AD). It was not until the Mongol Rouran Khaganate (330–555) of Xianbei origin that the word “Khagan” was used as an imperial title. Before being overthrown by the far greater Göktürks (555–745), it controlled a vast kingdom.

In 576, the Göktürks besieged Panticapaeum, or modern-day Kerch. After the Kyrgyz destroyed them, the Uyghur Khaganate (745–840) took over. Mongolia was dominated by the Mongolic Khitans, who were descended from the Xianbei, during the Liao Dynasty (907–1125), before the Khamag Mongols (1125–1206) gained dominance.

The history of the Khagans is summed up in lines 3-5 of the memorial inscription of Bilge Khagan (684–737) in central Mongolia:

They defeated and repressed the countries on all four sides of the globe in wars. Those with heads were forced to bow, and those with knees were forced to genuflect. They overran the ordinary people of Kadyrkhan in the east and the Iron Gate in the west. The Khagans possessed wisdom. These were magnificent Khagans. They had outstanding and smart servants as well. They were straightforward and honest with the public. This is how they dominated the country. They had control over them in this way. Ambassadors from several countries attended their funerals, including Kirgiz, Uch-Kurykan, Otuz-Tatars, Khitans, Tatabis, Tibet (Tibetan Empire), Tabgach (Tang China), Avar (Avar Khaganate), Rome (Byzantine Empire), and Bokuli Cholug (Baekje Korea).

Many gathered to grieve over the mighty Khagans. These were well-known Khagans.

From the Mongol Empire till the early 1900s

A leader by the name of Temüjin eventually brought the Mongol tribes between Manchuria and the Altai Mountains together during the instability of the late 12th century. After adopting the name Genghis Khan in 1206, he launched a string of fierce and bloody military expeditions throughout most of Asia, creating the Mongol Empire, the most contiguous land empire in recorded history.

Under his successors, it covered roughly 33,000,000 square kilometers (13,000,000 sq mi), or 22% of Earth’s total land area, and had a population of over 100 million, or roughly a quarter of the planet’s total population at the time. It stretched from what is now Poland in the west to Korea in the east, and from parts of Siberia in the north to the Gulf of Oman and Vietnam in the south. During its peak, Pax Mongolica’s establishment greatly facilitated trade and commerce across Asia.

Four kingdoms, or Khanates, emerged from the division of the empire following the death of Genghis Khan. Following Möngke Khan’s death in 1259, a power struggle that resulted in the Toluid Civil War (1260–1264) led to them finally becoming essentially autonomous. The Yuan dynasty was founded by Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, and comprised the Mongol homeland and much of present-day China. This was one of the khanates known as the “Great Khaanate”. Beijing is now the capital city that he established. Following the Ming dynasty’s collapse of the Yuan dynasty in 1368—more than a century after it had ruled—the Yuan court retreated to the north, whereupon it became the Northern Yuan dynasty.

The Mongol capital Karakorum and other cities were effectively looted and destroyed by the Ming army as they chased the Mongols into their homeland. Ayushridar and his commander Köke Temür led the Mongols in repelling some of these raids.

The Mongols referred to in history as the Northern Yuan dynasty, ruled their own territory after the Yuan emperors were driven out of China proper. It became known among them as “The Forty and the Four” (Döčin dörben) after the Mongol tribes split apart. The next centuries were characterized by many Ming invasions (including the five expeditions headed by the Yongle Emperor) and bloody power conflicts between numerous groups, most notably the Genghisids and the non-Genghisid Oirats.

Dayan Khan and his khatun Mandukhai brought all the Mongol tribes back under the Genghisid empire at the beginning of the 16th century. Dayan Khan’s grandson Altan Khan of the Tümed, who was not a genuine nor hereditary Khan, rose to prominence in the middle of the 16th century. In 1557, he founded Hohhot.

In 1578, following his meeting with the Dalai Lama, he gave the order to bring Tibetan Buddhism to Mongolia. (This happened for the second time.) In 1585, the Khalkha leader Abtai Khan established the Erdene Zuu monastery after converting to Buddhism. In 1640, his grandson Zanabazar rose to prominence as the first Jebtsundamba Khutughtu. The leaders converted to Buddhism, and all Mongolians followed. Scriptures and Buddha sculptures were stored by each family on an altar located on the north side of their yurt.

Monasteries received donations of land, cash, and herders from Mongolian nobility. As was common in kingdoms where religions were well-established, the leading religious establishments, the monasteries, possessed both spiritual and temporal power.

Ligden Khan, who lived in the early 17th century, was the final Khagan of the Mongols. He alienated most of the Mongol tribes and got into fights with the Manchus over the pillage of Chinese towns. In 1634, he passed away. The Manchus, who established the Qing dynasty, had subjugated the majority of the Inner Mongolian tribes by 1636. In 1691, the Khalkha finally yielded to the Qing authority, resulting in the Manchus ruling over all of modern-day Mongolia. The Qing conquered Dzungaria in 1757 and 1758, almost wiping out the Dzungars (western Mongols or Oirats) after many Dzungar–Qing Wars.

A mixture of sickness and conflict is thought to have killed 80% or more of the 600,000+ Dzungar, according to some academic estimates. The hereditary Genghisid khanates of Tusheet Khan, Setsen Khan, Zasagt Khan, and Sain Noyon Khan oversaw a comparatively autonomous Outer Mongolia. In Mongolia, the Jebtsundamba Khutuktu held great de facto power. The Mongols were able to preserve their culture because the Manchus prohibited large-scale Chinese immigration. The Oirats that moved to Russia’s Volga steppes were dubbed Kalmyks.

The Tea Road, which passed across Siberia, served as the primary trade route during this time. It included permanent stations spaced every 25 to 30 kilometers (16 to 19 mi), each of which was manned by five to thirty selected families.

The Qing dynasty used a number of alliances, intermarriages, military tactics, and economic policies to hold control over Mongolia until 1911. In Khüree, Uliastai, and Khovd, Manchu “high officials” known as ambans were appointed, and the nation was split up into several feudal and religious fiefdoms (which also put individuals in charge who were loyal to the Qing). During the course of the 1800s, the feudal lords began to place greater value on representation and less on their duties to their peasants. The nomads suffered from severe poverty as a result of the actions of Mongolia’s nobles, usurious tactics by Chinese traders, and the collecting of imperial taxes for money rather than animals.

Outer Mongolia had 700 big and minor monasteries by 1911, with 115,000 monks living there, accounting for 21% of the total population. In Outer Mongolia, in addition to the Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, there were thirteen additional reincarnating high lamas known as “seal-holding saints” (tamgatai khutuktu).

Contemporary history

Following the Qing dynasty’s collapse in 1911, Mongolia under the leadership of Bogd Khaan proclaimed its independence. However, Mongolia was seen as a component of the newly formed Republic of China’s boundaries. The President of the Republic of China, Yuan Shikai, saw the new republic as the Qing dynasty’s heir. According to Bogd Khaan, the agreement between Mongolia and the Manchus regarding Mongolia’s subjugation to them had become void with the fall of the Qing empire in 1911. The Manchus had ruled both China and Mongolia throughout the Qing period.

During the Qing era, the Bogd Khaan ruled over a region roughly equivalent to the old Outer Mongolia. Following the October Revolution in Russia in 1919, warlord Xu Shuzheng’s Chinese army invaded Mongolia. On the northern frontier, fighting broke out. Following the Russian Civil War, White Russian Lieutenant General Baron Ungern crossed into Mongolia in October 1920 and, with the help of the Mongols, defeated Chinese soldiers at Niislel Khüree (now Ulaanbaatar) in early February 1921.

In order to neutralize Ungern’s danger, Bolshevik Russia chose to back the formation of a communist army and government in Mongolia. On March 18, 1921, this Mongolian army drove Chinese soldiers out of the Mongolian portion of Kyakhta. On July 6, Russian and Mongolian troops landed in Khüree. On July 11, 1921, Mongolia proclaimed its independence once more. For the following seven decades, Mongolia maintained a tight ties with the Soviet Union as a result.

People’s Republic of Mongolia

The country’s governmental structure was altered in 1924 following the Bogd Khaan’s death from laryngeal cancer, or as other accounts assert, at the hands of Russian agents. The People’s Republic of Mongolia was founded. Khorloogiin Choibalsan became the ruler in 1928. Many of the early Mongolian People’s Republic (1921–1952) leaders had pan-Mongolist beliefs. Nevertheless, Pan-Mongol aspirations declined in the next years due to shifting international politics and growing Soviet pressure.

Stalinist purges led to the assassinations of many monks and other leaders, and Khorloogiin Choibalsan started the process of demolishing Buddhist monasteries and instituting the collectivization of cattle. In the 1920s, monks made up around one-third of the male population in Mongolia. In Mongolia, there were around 750 active monasteries at the start of the 20th century.

To avoid Mongolian reunification, the Soviet Union banned the Buryat people from migrating to the Mongolian People’s Republic in 1930. Stalin ordered the execution of all Mongolian leaders who refused to carry out Red Terror against their countrymen, including Peljidiin Genden and Anandyn Amar. More than 30,000 individuals perished in Mongolia during the Stalinist purges that started in 1937.

Official data indicates that 17,000 monks are thought to have perished in the Mongolian People’s Republic as a result of Stalinist influence. In charge of a dictatorship and orchestrating Stalinist purges in Mongolia from 1937 to 1939, Choibalsan passed away in 1952 under mysterious circumstances in the Soviet Union. The soil is more valuable than the people of Mongolia, according to Comintern leader Bohumír Šmeral. The area of Mongolia surpasses that of England, France, and Germany.

This front threatened Mongolia after the Japanese invaded nearby Manchuria in 1931. The Soviet Union successfully defended Mongolia from Japanese expansionism during the 1939 Soviet-Japanese Border War. In order to free Inner Mongolia from Mengjiang and Japan, Mongolia fought against Japan in the Battles of Khalkhin Gol in 1939 and the Soviet-Japanese War in August 1945.

Cold War

The Soviet Union was allowed to join the Pacific War as a result of the Yalta Conference in February 1945. At Yalta, the Soviet Union proposed that one of the requirements for its involvement be that Outer Mongolia maintain its independence following the war. On October 20, 1945, the referendum was held, and 100% of voters, according to official results, supported independence.

On October 6, 1949, upon the founding of the People’s Republic of China, both nations formally recognized one another. However, the Mongolian People’s Republic was not allowed to join the UN because the Republic of China used its Security Council veto power in 1955, claiming that all of Mongolia, including Outer Mongolia, was a part of China. The Republic of China only ever exercised its veto in this one instance. Therefore, as a result of the ROC’s constant threats to veto, Mongolia was prevented from joining the UN until 1961, when the Soviet Union consented to waive its veto on the entrance of Mauritania as well as any other newly independent African state in exchange for Mongolia’s admittance.

Under protest, the ROC gave in to pressure from almost all other African nations. On October 27, 1961, Mauritania and Mongolia were both admitted to the UN. (Refer to China and the UN.)

Following Choibalsan’s death on January 26, 1952, Yumjaagiin Tsedenbal became the new ruler of Mongolia. For over three decades, Tsedenbal dominated Mongolian politics. Tsedenbal’s serious sickness forced the parliament to announce his resignation and install Jambyn Batmönkh in his stead in August 1984 when Tsedenbal was visiting Moscow.

After the Cold War

The 1991 disintegration of the Soviet Union had a significant impact on youth and politics in Mongolia. In January 1990, its people carried out the nonviolent Democratic Revolution, which led to the establishment of a market economy and a multiparty government. The political landscape of the nation was also altered by the conversion of the previous Marxist-Leninist Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party into the present social-democratic Mongolian People’s Party.

1992 saw the introduction of a new constitution that eliminated the mention of the “People’s Republic” in the nation’s name. The country had severe food shortages and high inflation in the early 1990s, making the shift to a market economy difficult at times. Non-communist parties won their first elections in 1996 (parliamentary elections) and 1993 (presidential elections). China has endorsed Mongolia’s application to become an observer in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, as well as to join the Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD) and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).

Climate and Geography

Mongolia is the eighteenth biggest nation in the world, with 1,564,116 km2 (603,909 sq mi). It is substantially bigger than Peru, the next-largest nation. It is mostly located between longitudes 87° and 120°E and latitudes 41° and 52°N (with a tiny portion north of 52°). To put things in perspective, the northernmost portion of Mongolia is roughly located on the same latitude as Saskatoon, Canada, and Berlin, Germany, while the southernmost portion is roughly located on the same latitude as Rome, Italy, and Chicago, USA. Mongolia’s westernmost region is about on the same longitude as Kolkata, India, while its easternmost region is at the same longitude as Qinhuangdao, Hangzhou, and the western fringe of Taiwan in China.

Despite not having a border, Mongolia’s westernmost point is almost exactly a quadripoint, at just 36.76 kilometers (22.84 miles) from Kazakhstan.

Mongolia has a diverse topography, with the frigid, mountainous areas to the north and west and the Gobi Desert to the south. The Mongolian-Manchurian grassland makes up the majority of the country; forests make up 11.2% of the total land area, which is more than Ireland’s 10%. The Mongolian Plateau is said to include all of Mongolia. At 4,374 meters (14,350 feet), the Khüiten Peak in the Tavan Bogd range in the extreme west is the highest point in Mongolia. A natural World Heritage Site, the Uvs Lake basin is shared by Russia’s Tuva Republic.

Climate

With more than 250 sunny days each year, Mongolia is referred to as the “Country of Blue Sky” or the “Land of the Eternal Blue Sky” (Mongolian: “Mönkh khökh tengeriin oron”).

The majority of the nation has scorching summers and bitterly frigid winters, with January temperatures as low as −30 °C (−22 °F). Winter brings in a massive front of heavy, cold, shallow air from Siberia that gathers in low basins and river valleys, resulting in extremely frigid temperatures, while the effects of temperature inversion (heat rising with altitude) cause mountain slopes to be significantly warmer.

The Siberian Anticyclone affects the entirety of Mongolia throughout the winter. Uvs province (Ulaangom), western Khovsgol (Rinchinlhumbe), eastern Zavkhan (Tosontsengel), northern Bulgan (Hutag), and eastern Dornod province (Khalkhiin Gol) are the areas most badly impacted by this chilly weather. Strongly impacted but less so in Ulaanbaatar. Moving southward, the cold becomes less severe; the hottest January temperatures are found in Omnogovi Province (Dalanzadgad, Khanbogd) and the area around the Altai mountains that borders China. The fertile grassland-forest region of central and eastern Arkhangai Province (Tsetserleg) and northern Ovorkhangai Province (Arvaikheer) has a unique microclimate; in January, average temperatures there are not only more stable but also often higher than in the warmest desert regions to the south.

This microclimate is partly formed by the Khangai Mountains. The hottest town in this microclimate, Tsetserleg, experiences overnight lows of seldom less than −30 °C (−22 °F), and midday lows of often between 0 °C (32 °F) and 5 °C (41 °F).

Occasionally, the nation experiences severe weather known as zud. It causes a great deal of the nation’s cattle to perish from either frigid weather famine, or both, upsetting the economy of the predominantly pastoral people. Ulaanbaatar has the lowest average annual temperature in the world, at −1.3 °C (29.7 °F). Mongolia is windy, frigid, and high. The majority of the region’s yearly precipitation occurs during its short summers and lengthy, chilly winters, which characterize its harsh continental climate. With 257 clear days on average annually, the nation is often located in the middle of an area with high atmospheric pressure.

The north has the most precipitation, with an average of 200 to 350 millimeters (8 to 14 in) each year, while the south experiences the least, with 100 to 200 millimeters (4 to 8 in) per year. During the period 1961–1990, the woods of Bulgan Province, close to the Russian border, had the maximum annual precipitation of 622.297 mm (24.500 in), while the Gobi Desert recorded the lowest precipitation of 41.735 mm (1.643 in). With an average annual precipitation of 600 mm (24 in), the sparsely populated far north of Bulgan Province receives more precipitation than either Beijing (571.8 mm or 22.51 in) or Berlin (571 mm or 22.5 in).

Environmental Problems

In Mongolia, there are several urgent environmental problems that are harmful to the well-being of both people and the ecosystem. Although human activity has had a growing role, natural processes have also contributed to the emergence of these issues. Among these are the effects of climate change, which will exacerbate land degradation, natural catastrophes, and desertification.

Another is the increasing deforestation brought on by disease, fires, pests, and human activities. Due to careless land usage, Mongolian areas are experiencing desertification, which is making the region increasingly dry. In addition, an increasing number of species are in danger of going extinct or vanishing. In addition, industrialization has resulted in air and water pollution, which Mongolians must contend with, particularly in population centers.

Wildlife

The word “Gobi” comes from the Mongol word for “desert steppe,” which generally describes a type of dry rangeland that has enough flora to support camels but not enough to sustain marmots. Although foreigners unfamiliar with Mongolian terrain may not always notice the distinction, Mongols differentiate between the Gobi and the actual desert.

Overgrazing causes the actual desert, a rocky wasteland where not even Bactrian camels can live, to spread out of the fragile Gobi rangelands. The Himalayan rain shadow effect is thought to be responsible for the dry conditions found in the Gobi. Due to its remoteness from evaporation sources, Mongolia was a thriving home for a variety of significant fauna even before the Himalayas were created 10 million years ago by the collision of the Indo-Australian and Eurasian plates. Aside from the well-known dinosaur fossils, the Gobi has also yielded sea turtle and mollusk fossils. Even now, tadpole shrimp can still be found in the Gobi.

Lake Buir, the Onon and Kherlen rivers, and the eastern portion of Mongolia are all a part of the Amur river basin, which empties into the Pacific Ocean. It is home to a number of rare species, including the Siberian prawn (exopalaemon modestus) in Lake Buir, the Eastern brook lamprey, and the Daurian pearl oyster (dahurinaia dahurica) in the Onon and Kherlen rivers.

With a mean score of 9.36/10 on the 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index, Mongolia ranked sixth out of 172 nations worldwide.

Characteristics

The U.S. Census Bureau projected that as of January 2015, Mongolia has a 3,000,251 total population, placing it around 121st in the world. However, the United Nations (UN) estimates are used by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs rather than the estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. As of mid-2007, the Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs estimated that 2,629,000 people called Mongolia home, which is 11% fewer than the number reported by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The figures from the UN are similar to those from the National Statistical Office of Mongolia (2,612,900, as of June 2007). As of 2007, the population growth rate of Mongolia is expected to be 1.2%. Of all people, around 59% are under 30, with 27% being less than 14.

The comparatively youthful and expanding populace has imposed pressure on Mongolia’s economy.

In 1918, the first census of the 20th century was conducted, with a population count of 647,500. According to UN estimates, Mongolia’s total fertility rate (children per woman) has declined since the end of socialism more sharply than any other country in the world: from 7.33 children per woman in 1970–1975 to approximately 2.1 in 2000–2005, fertility has decreased more than any other country in the world. After a period of decrease that lasted from 2005 to 2010, the fertility value rose to 2.8 in 2013 and then stabilized at a rate of around 2.5 to 2.6 children per woman by 2020.

The ethnic Mongols, who make up around 95% of the population and are divided into Khalkha and other tribes, are largely characterized by their distinct dialects of the Mongol language. The Mongols are a reasonably homogenous people. Eighty-six percent of the ethnic Mongols are Khalkha. The remaining 14% consists of Buryats, Oirats, and other people. 4.5% of Mongolia’s population is made up of Turkic people, including Kazakhs and Tuvans; the other individuals are Russian, Chinese, Korean, and American citizens.

Verses

Mongolian is the official language of Mongolia. The standard dialect of Khalkha Mongol is a language belonging to the Mongolic language family. It coexists alongside Oirat, Buryat, and Khamnigan, among other mostly mutually intelligible dialects of Mongolic. In recent years, a number of dialects have changed to resemble the core Khalkha dialect. The majority of speakers of these dialects reside in the western regions of the nation, specifically in Bayan-Ölgii, Uvs, and Khovd. In Bayan-Ölgii, the predominant language is Kazakh, a Turkic language; in Khövsgöl, another Turkic language spoken is Tuvan. The primary language used by the deaf people in Mongolia is Mongolian Sign Language.

Since the 1940s, the Cyrillic script has been mostly used to write Mongolian. The ancient Mongolian script, which is still the official alphabet used by the Mongols in adjacent Inner Mongolia, has seen a slight resurgence after the revolution of 1990. Despite being taught in schools starting in the sixth grade and formally designated as the national script, Mongolian script is still mostly used for ceremonial purposes in everyday life. The Mongolian government said in March 2020 that official papers will be written in both the traditional Mongolian script and Cyrillic by 2025.

Russian has rapidly lost ground to English as the most widely spoken foreign language in Mongolia since 1990. Due to the high number of Soviet professionals and military stationed in Mongolia, as well as the significant number of students studying in the Soviet Union, Russian was an essential language for professional communication and movement throughout the communist era.

However, since then, the focus of Mongolia’s education system has shifted from the Soviet Union to the West, with the help of liberalized media, foreign assistance organizations, the growth of private education and tutoring, as well as official government policy, making English the country’s most widely spoken foreign language. 59% of all students in public secondary schools learned English during the 2014–2015 school year.

English was mandated to be taught starting in the third grade and designated as the “first foreign language” in 2023.

The most popular foreign languages in specialist language classes as of the 2014–2015 academic year were English, Chinese, Russian, Japanese, and Korean, in that order of popularity. Since South Korea employs tens of thousands of Mongolians, making up the biggest group of Mongolians abroad, Koreans in particular have grown in popularity.

Faith

In the 2010 National Census, 53% of Mongolians over the age of 15 identified as Buddhists, while 39% did not identify as religious.

Throughout the history of what is now Mongolia, shamanism has been extensively practiced, and nomads throughout central Asia have shared similar beliefs. They were eventually replaced by Tibetan Buddhism, although shamanism has remained a part of Mongolian religious life. Islam is the traditional religion of the Turkic peoples of Mongolia, including the Kazakhs living in western Mongolia and some Mongols.

Religious rituals were suppressed by the communist government for a large portion of the twentieth century. The target group was the Mongolian Buddhist Church clergy, who had a close relationship with the former feudal government institutions. For example, starting in 1911, the head of the Church was also the country’s Khan. At least 30,000 individuals were slaughtered in the late 1930s, virtually all of them were lamas, by the dictatorship, which was then headed by Khorloogiin Choibalsan. virtually all of Mongolia’s approximately 700 Buddhist monasteries were closed. Between 1924 and 1990, the number of Buddhist monks fell from 100,000 to 110.

After communism fell in 1991, religious practices in public were again allowed. Once again rising to prominence before communism took hold, Tibetan Buddhism is now the most frequently practiced religion in Mongolia. Beijing’s aim to exert control over Tibetan Buddhism is making the hunt for the next Jebtsundamba Khutuktu more difficult. Since the demise of the 9th Jebtsundamba in 2012, the position of highest-ranking lama in Mongolian Buddhism has remained empty.

Other religions were able to proliferate in the nation when religious persecution ended in the 1990s. The Christian missionary organization Barnabas Fund reports that as of 2008, there were over 40,000 Christians, up from just four in 1989. With 10,900 members and 16 church buildings around Mongolia, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) celebrated 20 years of its existence with a cultural event in May 2013. About a thousand people practice Catholicism in Mongolia, and the country’s first Catholic bishop was appointed in 2003 as a missionary from the Philippines. Seventh-day Adventists claimed 2,700 members in six congregations in 2017; before 1991, there were none.

Politics and Government

A directly elected president governs Mongolia, a semi-presidential representative democratic republic. Additionally, the State Great Khural representatives are chosen by the electorate. The prime minister is chosen by the president, who also proposes candidates for the cabinet. Numerous liberties are guaranteed under the Mongolian constitution, including complete freedom of speech and religion. The most recent amendment to Mongolia’s constitution was made in 2019 when the prime minister gained considerable authority over the president. The Mongolian parliament adopted a constitutional amendment on May 31, 2023, increasing the number of MPs from 76 to 126 and altering the election process to reinstate a proportional party vote.

The Democratic Party and the Mongolian People’s Party are the two biggest political parties in Mongolia. Mongolia is regarded as free by Freedom House, a non-governmental organization.

The People’s Party, which was called the People’s Revolutionary Party from 1924 to 2010, constituted the government from 2000 to 2004 and from 1921 to 1996 (when it operated as a one-party system until 1990). It was in a coalition with the Democrats and two other parties from 2004 to 2006, and it was the lead party in two more coalitions after that. Before losing control of the government in the 2012 election, the party started two changes of administration in 2004. Between 1996 to 2000, the Democrats dominated a coalition that ruled, and from 2004 to 2006, they partnered with the People’s Revolutionary Party approximately equally.

No party was able to secure an overwhelming majority in the national parliament following the June 28, 2012, deputy election. However, the Democratic Party secured the most seats, and its leader, Norovyn Altankhuyag, was named prime minister on August 10, 2012. He was succeeded in 2014 by Chimediin Saikhanbileg. Following the MPP’s resounding victory in the 2016 elections, Ukhnaagiin Khürelsükh of the MPP became the new prime minister. The MPP won the election with a resounding win in June 2020. Of the 76 seats, it won 62 while the principal opposition party, the DP, won 11. The electoral map was altered by the ruling party to benefit the MPP prior to the elections.

Ukhnaagiin Khürelsükh, the prime minister, resigned in January 2021 in response to demonstrations about a coronavirus patient’s care. Luvsannamsrai Oyun-Erdene of the MPP was appointed prime minister on January 27, 2021. He is a leader from a newer generation of leaders who studied overseas.

The president of Mongolia has the authority to veto legislation passed by parliament, choose justices of the peace, appoint judges, and designate diplomats. A two-thirds majority vote in the parliament is required to override the veto. According to the constitution, a candidate for president must be at least 45 years old, a native-born Mongolian, and have lived in the country for five years before to running for office. Additionally, the president has to revoke their party affiliation. Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj, a Democratic Party member and two-time prime minister, was elected president on May 24, 2009, and took office on June 18, having defeated incumbent Nambaryn Enkhbayar.

In October 2009, the People’s Revolutionary Party (2010), which is now in power in Mongolia, selected Batbold Sukhbaatar to be the next prime minister. Elbegdorj was sworn in for a second term as president on July 10, 2013, after being re-elected on June 26, 2013. The presidential election was won by Khaltmaagiin Battulga, a candidate from the opposition Democratic Party, in June 2017. He took office on July 10, 2017.

After winning the presidential election in June 2021, former prime minister Ukhnaa Khurelsukh, the candidate of the ruling Mongolian People’s Party (MPP), assumed the role of the nation’s sixth democratically elected leader.

The Speaker of the House presides over the 76-seat State Great Khural, which is the unicameral legislature of Mongolia. Its members are chosen directly by the general public every four years. In accordance with a 2023 constitutional revision, the parliament added 126 seats to the original 76.

International Relations

Mongolia’s two major neighbors, China and Russia, have historically dominated its foreign policy. These nations are Mongolia’s main economic partners: China accounts for 78% of its exports, significantly more than the next top nations (Switzerland at 15% and Singapore at 3%). China accounts for 36% of Mongolia’s imports, while Russia accounts for 29%. Through the Power of Siberia 2 natural gas pipeline, Mongolia is also seeking a trilateral collaboration with China and Russia. According to Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak, a deal would be completed in the “near future”. China is Mongolia’s main commercial partner, hence Mongolia has been attempting to avoid becoming involved in the present U.S.-China conflict.

It has started pursuing good ties with a greater variety of other nations, particularly in cultural and economic spheres, with an emphasis on promoting commerce and foreign direct investment. Since the early 1990s, Mongolia has pursued a “third-neighbor” foreign strategy in an effort to forge closer ties and alliances with nations outside of its two immediate borders.

Since its formation in 1992, Mongolia has been a part of The Forum of Small States (FOSS).

In 2011, then-U.S. Vice President Joe Biden traveled to Mongolia in favor of the country’s third neighbor policy.

Armed Forces

Mongolia backed the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and has since dispatched multiple contingents ranging from 103 to 180 soldiers to the country. There were about 130 soldiers sent to Afghanistan. In July 2009, Mongolia resolved to send a battalion to Chad in support of MINURCAT. Currently, 200 Mongolian troops are serving in Sierra Leone under a UN mandate to guard the UN special court established there.

About forty soldiers were stationed in Kosovo during 2005 and 2006 as part of the Belgian and Luxembourg contingents. George W. Bush visited Mongolia on November 21, 2005, making history as the first sitting US president to do so. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) welcomed Mongolia to become its newest Asian partner in 2004 while it was chaired by Bulgaria.

Legal Framework

The Mongolian judiciary is composed of three tiers of courts: the Supreme Court of Mongolia serves as the court of last resort (for non-constitutional matters); appellate courts are located in each province and the capital Ulaanbaatar; and first instance courts are located in each district of the province. There is a distinct constitutional court for matters pertaining to constitutional law.

Judges are nominated by the Judicial General Council (JGC), who must then have their nominations approved by parliament and appointed by the President.

For commercial and other conflicts, arbitration centers provide alternate methods of resolving disagreements.

Divisions of Administration

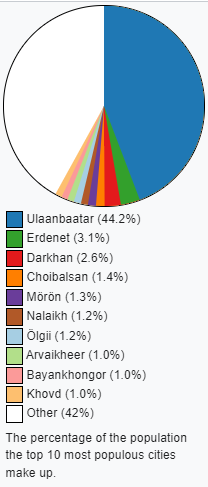

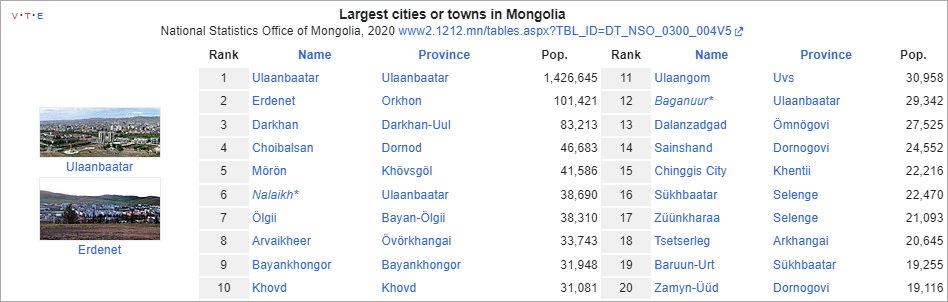

Large Cities

In 2020, Ulaanbaatar accounted for 47.6% of the total population, with another 21.4% residing in Darkhan, Erdenet, aimag centers, sum centers, and other permanent communities, and 31.0% in rural regions.

Finance

Although the development of vast mineral reserves of copper, coal, molybdenum, tin, tungsten, and gold has emerged as a driver of industrial output, Mongolia’s economy has traditionally been centered on agriculture and herding. In addition to mining (21.8%) and agriculture (16%), wholesale and retail trade and services, transportation and storage, and real estate sectors make up the majority of the GDP. Furthermore, one-fifth of the world’s raw cashmere is produced in Mongolia.

According to estimates, the size of the unofficial economy is at least one-third that of the official economy. In 2022, the PRC accounted for 36% of Mongolia’s imports while 78% of Mongolia’s exports were sent to that country.

According to the World Bank, Mongolia’s economic prospects are positive because of the country’s growing mining industry and significant public investment. However, there are also issues with inflation, China’s declining external demand, and ongoing fiscal problems brought on by the size of its contingent obligations. The Asian Development Bank estimates that in 2022, 27.1% of Mongolians were living below the poverty level. The projected GDP per person for that year was $12,100.

China’s robust demand for coal led to record-high coal output in 2023, which increased Mongolia’s real GDP by 7%. The early 2024 inflation rate fell to 7% as a result of declining global food and gasoline prices. Mongolia saw a current account surplus because of the rapid growth in coal exports, even with a strong increase in import amounts. GDP growth is anticipated to be driven by the mining industry, despite the International Monetary Fund’s prediction that falling coal prices will cause a large deficit in the current account balance.

Mongolia was identified by Citigroup analysts in 2011 as one of the “global growth generating” nations—those having the most promising development prospects between 2010 and 2050. Based on market capitalization, the Mongolian Stock Exchange, which was founded in Ulaanbaatar in 1991, is one of the smallest stock exchanges globally. Its 180 listed firms have a combined market value of US$3.2 billion as of 2024. According to the International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) scorecard for ease of doing business, Mongolia is presently ranked 81st internationally.

Mining Sector

Over 80% of Mongolia’s exports are made up of minerals, with that percentage projected to increase to 95% in the future. In 2010, fiscal receipts from mining accounted for 21% of government income; by 2018, that percentage had risen to 24%. There have been over 3,000 mining permits granted. The amount of Chinese, Russian, and Canadian companies establishing mining operations in Mongolia is proof positive that mining is still growing in importance as one of the country’s main industries.

The largest foreign investment project in Mongolia at the time, the Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold deposit, was to be developed under an agreement struck by the government of Mongolia with Rio Tinto and Ivanhoe Mines in 2009. With intentions to expand underground production and attain an output of 500,000 tons of copper annually, the mine is now a significant producer of both gold and copper. Legislators from Mongolia have also made an effort to provide funding for the development of the world’s largest undeveloped coal reserve, the Tavan Tolgoi region. Proposed global alliances, however, fell through in 2011 and 2015, and Mongolia also canceled a planned global IPO in 2020, citing political and economic challenges.

A major step toward Mongolia’s goal of becoming China’s top supplier of premium coal from the Tavan Tolgoi mine, which contains more than six billion tonnes of coal reserves, was taken in September 2022 when the country constructed and opened a 233-kilometer direct rail link to China.

Farming

Over 10% of Mongolia’s yearly GDP is generated by the agricultural sector, which also employs 1/3 of the working force. However, there is little chance for agricultural growth due to the high altitude, sharp temperature fluctuations, protracted winters, and little precipitation. There are just 95–110 days in the growth season. Most types of farming are not suitable for Mongolia due to its severe environment.

Because of this, the agricultural industry still mostly focuses on raising animals on nomadic farms, with 75% of the area utilized for grazing and only 3% of the workforce employed in crops. In Mongolia, raising cattle provided income for around 35% of all families. In Mongolia, the majority of herders practice semi-nomadic or nomadic pastoralism.

In Mongolia, potatoes, wheat, barley, and corn are grown. Mongolia raises sheep, goats, cattle, horses, camels, and pigs for commercial use. Goats are grown mostly for their meat, however their hair, which may be used to make cashmere, is also valuable. Climate change and land degradation are becoming bigger problems for livestock breeds.

Extreme weather events are occurring more frequently and with greater intensity, causing populations to suffer. One particularly harsh winter season known as a zud can decimate pasture and drop temperatures as low as -50°C. Zuds used to happen around once every 10 years, but in the last 10, there have been six. In the winter of 2024, these circumstances killed almost six million animals or 9% of all cattle.

Let’s imagine, explore, and uncover the mysteries together!

Let’s imagine, explore, and uncover the mysteries together!