Introduction

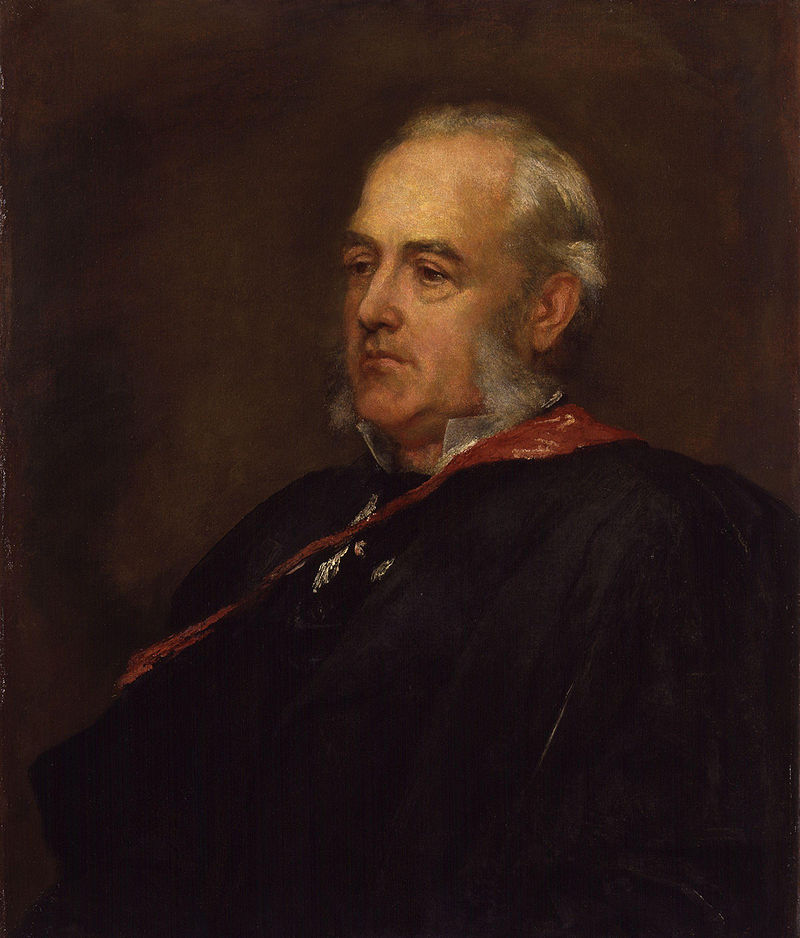

Friedrich Max Müller was a German-born comparative philologist and Orientalist who lived from December 6, 1823, to October 28, 1900. He was among the pioneers of the academic fields of Indology and Religious Studies in the West. Müller published on indology in both academic and popular publications. He oversaw the creation of the 50-volume English translation series known as the Sacred Books of the East.

Müller was appointed as an Oxford University professor, first of comparative philology and subsequently of contemporary languages, a post he kept for the remainder of his life. In the beginning of his professional life, he had strong opinions about India and thought that Christianity needed to change the country. Later on, his opinions softened and he started to support India in general as well as old Sanskrit literature. Throughout his career, he was embroiled in a number of controversy: he was charged with being anti-Christian; he supported theistic evolution over Darwinian evolution; he fostered interest in Aryan culture, strongly objecting to the racism that resulted from it; and he advanced the notion of a “Turanian” family of languages.

Among his many honors and distinctions are the Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art, membership in the Privy Council of the United Kingdom, and associé étranger of the French Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres.

Early life and education

On December 6, 1823, in Dessau, Max Müller was born into a well-educated family. His father, Wilhelm Müller, was a lyric poet whose poem Franz Schubert had put to music in his song cycles Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise. Adelheid Müller (née von Basedow), his mother, was the eldest child of an Anhalt-Dessau prime minister. One godfather was Carl Maria von Weber.

Müller was named after Max, the protagonist of Weber’s opera Der Freischütz, as well as Friedrich, the older brother of his mother. In later years, he added Max to his surname because he felt that Müller was too common a name. His name appeared as “Maximilian” in some publications and on several of his honors.

Müller enrolled at Dessau’s gymnasium, or grammar school, at the age of six. At the age of twelve, he was transferred to reside at Carl Gustav Carus’ home in Leipzig to attend the Nicolai School, where he further his classical and musical education, in 1835. It was at Leipzig that he had regular encounters with Felix Mendelssohn.

Müller, who needed a scholarship to go to Leipzig University, completed his abitur exam at Zerbst with success. He discovered during his preparation that the syllabus was different from what he had been taught and that he would need to pick up science, modern languages, and maths quickly. He gave up his early passion in poetry and music to pursue a degree in philology at Leipzig University in 1841. Müller graduated in September 1843 with a Ph.D. Spinoza’s Ethics was the subject of his last dissertation. His proficiency in ancient languages allowed him to acquire knowledge in Greek, Latin, Arabic, Persian, and Sanskrit.

Academic Trajectory

Müller joined Oxford University in 1850 as a deputy Taylorian professor of contemporary European languages. The next year he was elected to Christ Church, Oxford, as an honorary member and recipient of an M.A. honoris causa on Thomas Gaisford’s recommendation. By Decree of Convocation, he was awarded the full degree of M.A. upon succeeding to the full chair in 1854. He was chosen by All Souls’ College to receive a life fellowship in 1858.

A “keen disappointment” to him was his rejection in the 1860 election for the Boden Professorship of Sanskrit. Müller was significantly more competent for the position than Monier Monier-Williams, the other contender, but his lack of first-hand experience in India, Lutheranism, German ancestry, and religious beliefs worked against him. “All the best people voted for me, the Professors almost unanimously, but the vulgus profanum made the majority,” he wrote to his mother following the election.

Müller was appointed Oxford’s first professor of comparative philology later in 1868, a post created in his honor. Despite having stepped down from his active role in 1875, he kept this position until his death.

Iiterary and Scholarly Works

Sanskrit Academic Research

Before starting his studies at Oxford in 1844, Müller worked as Friedrich Schelling’s student in Berlin. He started translating the Upanishads for Schelling and worked with Franz Bopp, the first systematic scholar of the Indo-European languages (IE), on his Sanskrit studies. Müller was driven by Schelling to draw a connection between the history of religion and language. Müller’s first work, a translation of the Hitopadesa, a compilation of Indian stories, was released at this time in German.

Müller relocated to Paris in 1845 to study Sanskrit under Eugène Burnouf. Burnouf urged him to use the manuscripts that were in England to publish the whole Rigveda. In order to study Sanskrit books in the East India Company’s library, he relocated to England in 1846. His initial source of income was creative writing; at one point, German Love was a widely read novel.

Thanks to his associations with the East India Company and Oxford University Sanskritists, Müller was able to pursue a career in Britain, where he finally rose to prominence as the foremost scholar commentator on Indian culture. This region was under British Empire administration at the time. The result was a complicated flow of intellectual culture between Indian and British, particularly via Müller’s connections to the Brahmo Samaj.

Müller studied Sanskrit during a period when researchers began to consider language evolution in terms of cultural development. There has been a lot of conjecture on the connection between Greco-Roman and prehistoric cultures since the discovery of the Indo-European language group. Specifically, it was believed that European Classical traditions descended from the Indian Vedic culture. In an effort to recreate the oldest version of the root language, researchers compared the genetically related European and Asian languages. It was formerly believed that Sanskrit, the language of the Vedas, was the oldest of the IE languages.

Müller became one of the leading Sanskrit experts of his day by devoting his life to the study of this language. He thought that the key to understanding the evolution of pagan European faiths and of religious belief in general might be found in an examination of the oldest Vedic cultural records. Müller aimed to comprehend the Rig-Veda, the oldest of the Vedic texts, in order to do this. Sayanacharya, a 14th-century Sanskrit scholar, wrote the Rigveda Samhita book, which Müller translated from Sanskrit into English. Müller published many works and articles about his contemporary, Vedantic philosopher Ramakrishna Paramhansa, who deeply affected him.

Müller believed that studying a language had to have a connection to studying the culture in which it was used. He concluded that the evolution of belief systems and languages need to be connected. Though there was growing interest in the Upanishads’ philosophy at the time, the Vedic texts were not well recognized in the West. Müller thought there was a connection between the crude henotheism of early Vedic Brahmanism and the complex Upanishadic philosophy from which it arose. To view records in the British East India Company’s collection, he had to fly to London.

He convinced the firm to let him work on a critical edition of the Rig-Veda while he was there, and he pursued this endeavor for several years (1849–1874). He finished the crucial version for which he is well known.

Müller believed that the Vedic peoples practiced a kind of nature worship, which was obviously affected by Romanticism. Müller’s depiction of ancient religions was influenced by many of the Romantic ideals that he shared, particularly his focus on the formative role of emotional connection with natural forces on early religion. The gods of the Rig Veda, in his view, were not so much imagined supernatural beings as they were dynamic forces of nature. Müller’s thesis that mythology is “a disease of language” stems from this assertion. This was his way of saying that thoughts become creatures and tales through myth. Müller believed that the term “gods” evolved from terms used to convey abstract concepts into made-up personas.

Thus, the father-god of Indo-Europeans goes by several titles, including Zeus, Jupiter, and Dyaus Pita. Müller believed that the term “Dyaus,” which he took to mean “shining” or “radiance,” was the source of all these names. As general words for gods, this gives rise to the phrases “deva,” “deus,” and “theos,” as well as the names “Zeus” and “Jupiter” (derived from deus-pater). A metaphor gets personified and ossified in this way. Nietzsche later investigated this same area of Müller’s thought.

Gifford Lectures

Müller was named a Gifford Lecturer at Glasgow University in 1888. These Gifford Lectures were the first of a yearly series that has persisted to this day at several Scottish institutions. Müller delivered four series of lectures in the next four years. The lectures had the following names and sequence:

- Organic Spirituality. The goal of this inaugural lecture course was to define natural religion in its broadest meaning. It was meant to be entirely introductory.

- Religion in the physical world. The goal of this second series of lectures was to demonstrate how many cultures came to believe in several invisible agents or gods of nature, in something infinite behind the finite, and in something invisible behind the visible, all the way up to believing in one god above all those gods. A brief chronicle of the discoveries made on the infinite in nature.

- Religion in Anthropology. The purpose of this third course was to demonstrate how diverse cultures came to believe in the existence of a soul, how they gave names to its distinct capacities, and what they thought would happen to it after death.

- Theosophy or Psychological Religion. The fourth and last course of lectures was intended to examine the relation between God and the soul (“these two Infinites”), including the ideas that some of the principal nations of the world have formed concerning this relation. Real religion, Müller asserted, is founded on a true perception of the relation of the soul to God and of God to the soul; Müller wanted to prove that this was true, not only as a postulate, but as an historical fact. The original title of the lectures was ‘Psychological Religion’ but Müller felt compelled to add ‘Theosophy’ to it. Müller’s final Gifford Lecture is significant in interpreting his work broadly, as he situates his philological and historical research within a Hermetic and mystical theological project

In the role of interpreter

He translated the first edition of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and published it in 1881. He concurred with Schopenhauer that this version represented Kant’s ideas in the most straightforward and truthful way. Several mistakes made by earlier translators were fixed in his translation. Müller stated in his Translator’s Preface:

The Veda contains the first arch of the bridge of ideas and sighs that spans the entire history of the Aryan world, while Kant's Critique contains the last arch. While we may study boyhood in the Veda, we can study the ideal manhood of the Aryan intellect in Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. Now that the resources are available, the English-speaking race—the race of the future—will possess another priceless Aryan treasure, equal in value to the Veda—Kant's Critique. This work is subject to criticism but cannot be disregarded.

Müller rejected Darwinian theories of human development and remained inspired by the Kantian Transcendentalist spirituality paradigm. He maintained that “language forms an impassable barrier between man and beast.”

Opinions toward India

Early professional life

To Chevalier Bunsen, Müller wrote on August 25, 1866:

Compared to Rome or Greece at the time of St. Paul, India is far more conducive to Christianity. The decaying tree has been artificially supported for a while now since the government would have found it inconvenient if it had fallen. However, if the Englishman realizes that the tree will eventually fall, then all is done. I would like to give up my life, or at the very least, help to start this battle. Being a missionary in India makes one dependant on the Parsons, therefore I detest going there.

I would like to live a tranquil life for 10 years, attempt to learn the language, make some friends, and determine if I’m capable of working on a project that would clear the path for the introduction of straightforward Christian doctrine and bring an end to the long-standing mischief of Indian priestcraft.

— The Right Honorable Friedrich Max Müller’s Life and Letters, Volume I, Chapter X

Throughout his career, Müller often voiced the opinion that Hinduism needed a “reformation” along the lines of the Christian Reformation. According to him, “if there is one thing which a comparative study of religions places in the clearest light, it is the inevitable decay to which every religion is exposed… Whenever we can trace back a religion to its first beginnings, we find it free from many blemishes that affected it in its later states” .

Utilizing his connections with the Brahmo Samaj, he promoted a reformation along the same lines as those initiated by Ram Mohan Roy. Müller thought that the Brahmos were in reality “Christians, without being Roman Catholics, Anglicans, or Lutherans,” and that they would spread an Indian version of Christianity. He believed that the “superstition” and idolatry that he saw as inherent in contemporary popular Hinduism would vanish inside the Lutheran heritage.

Müller penned:

The future of India and the development of millions of souls there will be greatly revealed by the Vedic translation. It is the foundation of their faith, and I believe that the only way to destroy everything that has grown out of it over the past 3,000 years is to reveal to them what the foundation is. One should thus get up and start working on whatever may be God's will.

Müller believed that more money for education in India would encourage the emergence of a new kind of literature that blended Indian and Western influences. He wrote to the recently appointed Secretary of State for India, George Campbell, in 1868:

India has already been subjugated once; nonetheless, a second conquest is necessary, and it need to be accomplished by education. Although a lot has been done recently to support education, even a triple or quadruple increase in funding would not be sufficient (…) Those in positions of power over big populations will be able to rekindle a sense of pride and self-respect for their country by promoting the study of their own ancient literature as part of their education. It’s possible for a new national literature to emerge, infused with Western concepts while keeping its essence and identity. A new national literature will infuse the country with new vitality and morality. Regarding religion, that will resolve itself. The missionaries have accomplished considerably more than they appear to be aware of; in fact, they would likely deny doing much of the work that is really theirs. There’s no chance that India’s Christianity will resemble that of the eighteenth century. However, the age-old Indian religion is doomed; who will be at fault if Christianity does not intervene?

— Max Müller (1868)

Late career

Müller delivered a number of lectures in his sixties and seventies that revealed a more nuanced perspective in favor of Hinduism and Indian literature from antiquity. He defended ancient Sanskrit literature and India in the following ways at his “What can India teach us?” talk at the University of Cambridge:

If I had to survey the entire planet to determine which nation possesses the most plenty, might, and natural beauty—in certain regions, an absolute heaven on earth—I would have to say that India tops the list. India is the place where, in my opinion, the human intellect has fully realized some of its greatest talents, has thought most carefully about life’s biggest issues, and has come up with answers for some of them that even people who have studied Plato and Kant should find worthy of consideration. If I were to inquire about the literature that we in Europe, who have been raised primarily on the ideas of the Greeks, Romans, and one Semitic race, the Jews, might read to obtain the necessary correction to make our inner lives more flawless, all-encompassing, universal, and truly human—that is, a life that transcends this life and is eternal—I would again have to mention India.

— Max Müller (1883)

Müller speculated in a different lecture titled “Truthful Character of the Hindus” that the arrival of Islam to India in the eleventh century had a profound impact on Hindu psychology and behavior:

There are other instances in the other epic poetry, the Mahabharata, that demonstrate a deep reverence for the truth. (*) If I were to cite every legal book and every later work, you would find that they all have the same fundamental message of honesty resonating through them. (…) I reiterate that while I do not wish to speak for two hundred and fifty-three million Indians as angels, I do want it acknowledged as a fact that the damaging accusation of dishonesty leveled against them is wholly baseless in the context of historical events. Not only is it untrue, but it is also completely false. Regarding the present era, which I define as beginning approximately 1000 AD, all I can say is that, having read about the atrocities and terrors of Mohammedan tyranny, I find it astonishing that so much of the original virtues and truths should have survived. A mouse in front of a cat is about as likely to tell the truth as a Hindu in front of a Mohammedan judge.

— Max Müller (1884)

On May 28, 1896, Swami Vivekananda, the leading follower of Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, had lunch with Müller. On Müller and his spouse, the Swami subsequently wrote:

For me, the experience was quite enlightening. That noble wife, his helpmate through his long and arduous task of stimulating interest, overriding opposition and contempt, and finally creating a respect for the thoughts of the sages of ancient India—the trees, the flowers, the calmness, and the clear sky—that little white house, its setting in a beautiful garden, the silver-haired sage, with a calm and benign face and forehead smooth as a child's in spite of seventy winters—all of these transported me back in my mind to the illustrious bygone era of ancient India, the era of our rajarshis and brahmarshis, the era of the great vanaprasthas, the era of Arundhatis and Vasishthas. I saw a soul that is discovering its unity with the cosmos on a daily basis, not the philologist or the professor.

Disputes

Hostile to Christianity

Müller faced harsh criticism for being anti-Christian during his Gifford Lectures on the topic of natural religion. Müller’s appointment as lecturer was questioned in 1891 when Mr. Thomson, the Minister of Ladywell, moved a motion at a meeting of the Established Presbytery of Glasgow, claiming Müller’s teaching was “subversive of the Christian faith, and fitted to spread pantheistic and infidel views amongst the students and others”.

In St Andrew’s Cathedral, Monsignor Alexander Munro launched an even more vicious attack against Müller. Müller’s lectures “were nothing less than a crusade against Divine revelation, against Jesus Christ, and against Christianity,” according to Munro, a Roman Catholic Church official in Scotland who served as provost of the Catholic Cathedral of Glasgow from 1884 to 1892.

He went on to say that the blasphemous lectures “uprooted our idea of God, for it repudiated the idea of a personal God” and were “the proclamation of atheism under the guise of pantheism”.

Müller had already lost out to the more traditional Monier Monier-Williams for the Boden chair in Sanskrit as a result of similar charges. Theosophist Helena Blavatsky, Charles Godfrey Leland, and other writers vying to promote the superiority of paganism over Christianity began courting Müller in the 1880s. According to designer Mary Fraser Tytler, her “Bible” for creating multi-cultural religious imagery was Müller’s book Chips from a German Workshop, which is a compilation of his lectures.

Müller stayed true to his upbringing as a Lutheran and disassociated himself from these developments. Müller’s association with the Broad Church party and his Lutheran German heritage, according to G. Beckerlegge, “led to suspicion by those opposed to the political and religious positions that they felt Müller represented,” especially Müller’s latitudinarianism.

Müller’s Perennialism was based on the conviction that Christianity held the fullest truth of all living religions, despite his strong religious and academic interest in Hinduism and other non-Christian religions. Müller frequently made comparisons between Christianity and religions that many traditional Protestants would have considered to be primitive or false.

Rather than accusing Müller of being anti-Christian, religious scholars of the twenty-first century have critically analyzed Müller’s theological endeavor as proof of a bias in favor of Christian conceptions of God in the early stages of academic religious studies.

Darwin’s Dispute

Müller made an effort to develop a theology that addressed the crisis of faith brought about by the Darwinian revolution and the historical and critical examination of religion by German academics. Darwin’s theory of the evolution of human abilities was criticized by him, and he was skeptical of his work on human evolution.

Cultural critics like his friend John Ruskin picked up on his work because they believed it was a useful answer to the crises of the day. He examined mythology as explanations for natural events, as early origins that we may refer to as “protoscience” in the context of cultural development. Müller used Darwinism as a weapon against mechanical philosophy in order to present an early, mystical interpretation of theistic evolution.

Müller presented a three-part series of lectures titled “On Darwin’s Philosophy of Language” at the British Institution in 1870 on language as the divide between humans and animals. Müller expressly disagreed with Darwin’s hypotheses on the origin of language and the possibility that animal language evolved into human language. He assured Darwin that even if he disagreed with some of his findings, he was one of his “diligent readers and sincere admirers” in 1873 when he provided a copy of his lectures.

Aryanism

The growing interest in Aryan culture, which frequently pitted Indo-European (“Aryan”) customs against Semitic faiths, was aided by Müller’s study. Though this was not at all his aim, he was “deeply saddened by the fact that these classifications later came to be expressed in racist terms”. Müller used the finding of shared Indian and European ancestry as a powerful argument against racism, claiming that “the blackest Hindus represent an earlier stage of Aryan speech and thought than the fairest Scandinavians” and that “an ethnologist who speaks of Aryan race, Aryan blood, Aryan eyes and hair, is as great a sinner as a linguist who speaks of a dolichocephalic dictionary or a brachycephalic grammar.”

Turanian

Müller proposed and supported the idea that the Finnic, Samoyedic, Mongolic, Tungusic, and “Tataric” (Turkic) languages belong to a “Turanian” family of languages or speech. “Spoken in Asia or Europe not included under the Arian [sic] and Semitic families, with the possible exception of the Chinese and its dialects,” Müller said, were these five languages. Moreover, he referred to the other two groups (Aryan and Semitic) as “state or political languages,” when they were “nomadic languages.”

The notion of a Turanian language family was not widely acknowledged at the time. The name “Turanian” did not entirely vanish, even if it soon became an archaism (unlike “Aryan”). Later, nationalist ideologies like Turkey and Hungary adopted the notion.

Awards and distinctions

Müller was elected as a foreign correspondent (associé étranger) to the French Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in 1869.

To his astonishment, Müller received the Pour le Mérite (civil class) medal in June 1874. He wrote to Prince Leopold shortly after being told to eat at Windsor to inquire about wearing his Order, and the reply was, “Not may, but must.”

The Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art was given to Müller in 1875. The prize is granted to recognize exceptional and noteworthy contributions to the fields of science and art. Müller said that the prize was “but that is the best” in a letter to his mother dated December 19, even if it was more ostentatious.

Müller was appointed to the Privy Council in 1896.

Individual life

At the age of 32, Müller obtained British citizenship in 1855. On August 3, 1859, he wed Georgina Adelaide Grenfell, despite her family’s resistance. Ada, Mary, Beatrice, and William Grenfell were the couple’s four children; two of them passed away before them. His papers and correspondence, bound by Georgina (d. 1919), are held by the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Demise and inheritance

Müller’s health started to decline in 1898, and on October 28, 1900, he passed away at home in Oxford. He was buried on November 1, 1900, in Holywell Cemetery.

The Max Müller Memorial Fund was established at Oxford University in his honor following his passing with the goal of advancing “learning and research in all matters relating to the history and archaeology, the languages, literatures, and religions of ancient India.”

“The first part depicts the heroine’s toothache consequent to the loss of a valuable watermelon, her dentistry, and her transportation to heaven,” said Harry Smith of his film Heaven and Earth Magic. An intricate description of the heavenly country in terms of Israel and Montreal is then presented, and the second section shows Max Müller’s return to Earth on the day when Edward the Seventh consecrated London’s Great Sewer.”

Max Müller Bhavan is the name of the Goethe Institutes in India; Max Mueller Marg is a roadway in New Delhi dedicated in his honor.

Chaudhuri (1974), Stone (2002), and Van den Bosch (2002) are some of Müller’s biographies. The Sahitya Akademi Award for English was given to Scholar Extraordinary by Nirad C. Chaudhuri by Sahitya Akademi, the National Academy of Letters of India. Furthermore, Müller’s competition with American linguist William Dwight Whitney is covered in a chapter of Stephen G. Alter’s 2005 book William Dwight Whitney and the Science of Language.