Writing and literacy

One of the outstanding achievements of the pre-Columbian inhabitants of the Americas is the Maya writing system. More advanced and highly developed than a dozen other systems developed in Mesoamerica, it was the most advanced. The earliest inscriptions in an identifiably Maya script date to the period 300–200 BC in the Petén Basin.

However, this is preceded by several other Mesoamerican writing systems, such as the Epi-Olmec and Zapotec scripts. Early Maya script had appeared on the Pacific coast of Guatemala by the late 1st century AD, or early 2nd century. Similarities between the Isthmian script and Early Maya script of the Pacific coast suggest that the two systems developed in tandem. By about AD 250, the Maya script had become much more formalized and uniform.

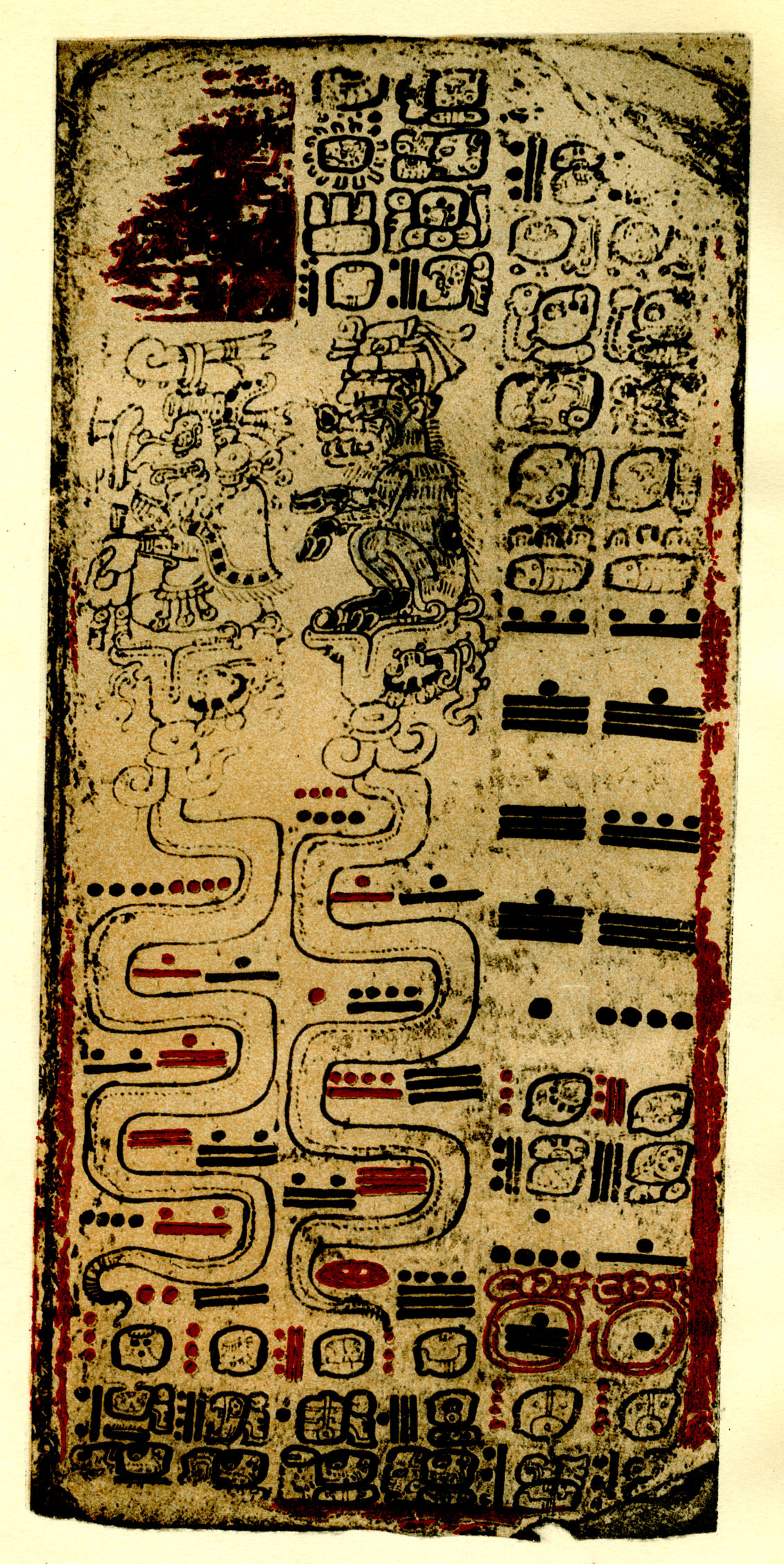

The Catholic Church and colonial officials, in particular Bishop Diego de Landa, destroyed Maya texts wherever they found them and, with them, the knowledge of Maya writing. By chance, however, four uncontested pre-Columbian books from the Postclassic period have survived.

These are called the Madrid Codex, the Dresden Codex, the Paris Codex, and the Maya Codex of Mexico formerly known as the Grolier Codex which authenticity had long been disputed until 2018. Archaeology performed at the Maya sites usually uncovered other fragments, rectangular lumps of plaster, and paint chips that were codices.

These tantalizing remains, however, are too severely damaged for any inscriptions to have survived, most of the organic material having decayed. In reference to the few extant Maya writings, Michael D. Coe stated:

Our knowledge of ancient Maya thought must represent only a tiny fraction of the whole picture, for of the thousands of books in which the full extent of their learning and ritual was recorded, only four have survived to modern times (as though all that posterity knew of ourselves were to be based upon three prayer books and ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’).

— Michael D. Coe, The Maya, London: Thames and Hudson, 6th ed., 1999, pp. 199–200.

Most surviving pre-Columbian Maya writing dates to the Classic period and is contained in stone inscriptions from Maya sites, such as stelae, or on ceramics vessels. Other media include the aforementioned codices, stucco façades, frescoes, wooden lintels, cave walls, and portable artefacts crafted from a variety of materials, including bone, shell, obsidian, and jade.

Writing system

Maya Writing System: The Maya script is often called hieroglyphs because of superficial similarities with Ancient Egyptian writing. A logosyllabic writing system, it combines a syllabary of phonetic signs representing syllables and logograms representing entire words. More than any other writing systems for the Pre-Columbian New World, Maya script most closely represents the spoken language. At any given time, no more than 500 glyphs were in use, of which some 200 (with variations) phonetic.

The Maya word Bʼalam (“jaguar”) written twice in the Maya script. The first glyph writes the word logographicaly with the jaguar head standing for the entire word. The second glyph block writes the word phonetically using the three syllable signs BA, LA and MA.

The Maya script was in use up to the arrival of the Europeans, with its use peaking during the Classic Period. More than 10,000 individual texts have been recovered, mostly inscribed on stone monuments, lintels, stelae, and ceramics. The Maya also produced texts painted on a form of paper manufactured from processed tree-bark, generally now known by its Nahuatl-language name amatl, which was used to produce codices. The knowledge of writing and writing ability persisted within segments of Maya population even up to the Spanish conquest. However, as an impact of conquest upon the Maya society, that knowledge was lost thereafter.

Decipherment and Recovery of Knowledge in Maya Writing This has been a long, laborious process. Elements of decipherment date from the end of the 19th and early 20th century; these include, in general, numbers, the calendar, and astronomy. Most major breakthroughs occurred from the 1950s to the 1970s, after which progress accelerated rapidly. Scholars, by the end of the 20th century, could read most of Maya texts; ongoing work continues to shine more light on their contents.

Logosyllabic script

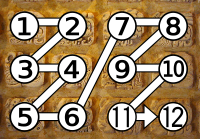

The basic form of Maya logographic and syllabic texts is the glyph block, meaning a whole word or short phrase. Usually, the blocks consist of one or two glyphs bound to each other, sometimes attached to different glyph blocks; individual blocks are usually kept apart by means of a blank space. Mostly, glyphs blocks are grouped in a regular grid pattern. For ease of reference, epigraphers refer to glyph blocks from left to right alphabetically, and top to bottom numerically.

Thus any glyph block in a piece of text can be identified. C4 would be the third block counting from the left, and the fourth block counting downwards. In case a monument or an artifact has more than one inscription, column labels are not repeated; they continue instead in the alphabetic series. If there are more than 26 columns, labeling continues as A’, B’, etc. Row labels numbering in the row starts anew with 1 for every distinct unit of text.

Although Mayan text can sometimes be laid out in varying fashions, it’s usually set up in double columns of glyph blocks. The reading of the text begins on top left (block A1), across to the second block on the double column (B1), then drops a row and starts again from the lefthand half of the double column (A2), and continues zig-zag from there. Once the bottom is reached, the inscription continues from the top left of the next double column (C1). When an inscription ends in a single (unpaired) column, this final column is normally read straight down.

Individual glyph blocks may comprise a number of elements. These include the basic sign and any affixes. Basic signs make up the main element of the block and may be a noun, verb, adverb, adjective, or phonetic sign. Some of these are abstract, others pictorial representations of the thing it stands for, while yet others are “head variants,” personifications of the word they stand for.

Affixes are smaller rectangular elements, usually attached to a main sign, although a block may be composed entirely of affixes. Affixes may represent a wide variety of speech elements, including nouns, verbs, verbal suffixes, prepositions, and pronouns. Small sections of a main sign could be used to represent the whole main sign. Maya scribes were highly inventive in their usage and adaptation of glyph elements.

Writing tools

Although the archaeological record yields no examples of brushes or pens, study of ink strokes on the Postclassic codices indicates that it was applied with a brush featuring a tip fashioned from pliable hair. A sculpture from the Classic period discovered at Copán, Honduras, shows a scribe in possession of an inkpot composed of a conch shell. Excavations carried out at Aguateca uncovered a number of scribal artifacts from the homes of elite status scribes, including palettes and mortars and pestles.

Scribes and literacy

Commoners were in general illiterate; the scribes were drawn from the elite. It is unknown whether all members of the aristocracy could read and write, although at least some women could, as there are representations of female scribes in Maya art. Maya scribes were known as aj tz’ib, which means “one who writes or paints.” There probably existed scribal schools where members of the aristocracy were taught how to write.

Scribal activity is visible in the archaeological record; Jasaw Chan Kʼawiil I, king of Tikal, was buried with his paint pot. Some junior members of the Copán royal dynasty have been found buried with their writing tools. A palace at Copán has been identified as that of a noble lineage of scribes; it is decorated with sculpture that includes figures holding ink pots.

Although not much is known about Maya scribes, some did sign their work, both on ceramics and on stone sculpture. Usually, only a single scribe signed a ceramic vessel, but multiple sculptors are known to have recorded their names on stone sculpture; eight sculptors signed one stela at Piedras Negras. However, most works remained unsigned by their artists.

Mathematics

In common with the other Mesoamerican civilizations, the Maya used a base 20 (vigesimal) system. The bar-and-dot counting system that is the base of Maya numerals was in use in Mesoamerica by 1000 BC; the Maya adopted it by the Late Preclassic and added the symbol for zero. This may have been the earliest known occurrence of the idea of an explicit zero worldwide, although it may have been later than the Babylonian system.

The earliest explicit use of zero occurred on monuments dated to 357 AD. In its earliest uses, zero served as a placeholder, indicating an absence of a particular calendrical count. This later developed into a numeral that was used to perform calculations and was used in hieroglyphic texts for more than a thousand years, until the writing system was extinguished by the Spanish.

The base number system used a dot to represent one and a bar to represent five. A shell symbol represented zero by the Postclassic period; during the Classic period, other glyphs were used. The Maya numerals from 0 to 19 were constructed using repetitions of these symbols. The value of a numeral was determined by its position; as a numeral shifted up, its basic value multiplied by twenty.

In this method, the lowest symbol could represent units, the one above it could represent multiples of twenty, and the third one up could represent multiples of 400, etc. For example, the number 884 would be written using four dots on the bottom level, four dots on the next level up, and two dots on the following level above that, as follows: 4 x 1 + 4 x 20 + 2 x 400 = 884. This system let the Maya record enormous numbers. Simple addition could be achieved by adding the dots and bars in two columns and showing the result in a third column.

Calendar

The Maya calendrical system had its origins in the Preclassic period, as with most other Mesoamerican calendars. However, it is the Maya who developed the calendar to maximum sophistication, recording lunar and solar cycles, eclipses, and movements of planets with a great degree of accuracy. In some instances, the Maya calculations were more accurate than equivalent calculations in the Old World; for example, the Maya solar year was calculated to greater accuracy than the Julian year.

The Maya calendar was intrinsically tied to Maya ritual and was central to Maya religious practices. The calendar combined a non-repeating Long Count with three interlocking cycles, each measuring a progressively larger period.

These included the 260-day tzolk’in, the 365-day haab’, and the 52-year Calendar Round, generated by combining the tzolk’in with the haab’. The other cycles included an 819-day cycle tied to the four quadrants of Maya cosmology, each controlled by a different aspect of the god Kʼawiil.

The basic unit in the Maya calendar was one day, or k’in, and 20 k’in grouped to form a winal. The next unit, instead of being multiplied by 20, as called for by the vigesimal system, was multiplied by 18 to provide a rough approximation of the solar year (thus producing 360 days). This 360-day year was called a tun. Each succeeding level of multiplication followed the vigesimal system.

The 260-day tzolk’in provided the basic cycle of Maya ceremony and the foundations of Maya prophecy. There is no astronomical basis proven for this count, and it may be that the 260-day count is based on the human gestation period. This is supported by the use of the tzolk’in to record dates of birth and give corresponding prophecy. The 260-day cycle repeated a series of 20-day names, with a number from 1 to 13 prefixed to indicate where in the cycle a particular day occurred.

The 365-day haab’ was comprised of a cycle of eighteen named 20-day winals, completed by the addition of a 5-day period called the wayeb. This last period was considered to be dangerous, as barriers were said to be broken that separate the mortal and supernatural realms, allowing malignant deities to cross over and interfere in human concerns.

In a similar way to the tzolk’in, the named winal would be prefixed by a number from 0 to 19 and, in the case of the shorter wayeb period, the prefix numbers ran from 0 to 4. Because each day of the tzolk’in had a name and number-for example, 8 Ajaw-this would interlock with the haab’, producing an additional number and name, so that any day had a more complete designation-for example, 8 Ajaw 13 Keh. A day name could only recur once every 52 years, and this period is called by Mayanists the Calendar Round. In most Mesoamerican cultures, the Calendar Round was the largest unit for measuring time.

Unlike the non-repeating calendar of any other civilization, Maya measurement of time started from an absolute start point. Mayas chose the starting of the calendar at the end of a previous cycle of bak’tuns that equal one day in 3114 BC. This day they perceived the beginning, as per their mythology to mark when their world came into being as per its present form.

The Maya used the Long Count Calendar to position any given day of the Calendar Round into their present great Piktun cycle, either being 20 bak’tuns long. The calendar varied and, specifically, the Palenque texts reveal that the Piktun cycle that ended in 3114 BC only used 13 bak’tuns, whereas some used a cycle of 13 + 20 bak’tuns in the present Piktun. In addition, perhaps the way these exceptional cycles were managed varied by region.

A complete Long Count date began with an introductory glyph and then had five glyphs that counted off the number of bak’tuns, kat’uns, tuns, winals, and k’in since the beginning of the current creation. This would be followed by the tzolk’in portion of the Calendar Round date, and after a number of intervening glyphs, the Long Count date would end with the Haab’ portion of the Calendar Round date.

Correlation of the Long Count calendar

While the Calendar Round is still observed today, the Maya used an abridged Short Count beginning during the Late Classic period. The Short Count is a count of 13 k’atuns. The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel has the only colonial reference to classic Long Count dates. The most generally accepted correlation is the Goodman-Martínez-Thompson, or GMT, correlation. This equates the Long Count date 11.16.0.0.0 13 Ajaw 8 Xul with the Gregorian date of 12 November 1539.

Epigraphers Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube argue for a two-day shift from the standard GMT correlation. The Spinden Correlation would throw the Long Count dates back by 260 years; it also agrees with the documentary evidence and is better for the archaeology of the Yucatán Peninsula, but it has problems with the rest of the Maya region. The George Vaillant Correlation would shift all Maya dates 260 years later and would greatly shorten the Postclassic period. Radiocarbon dating of dated wooden lintels at Tikal supports the GMT correlation.

Latest Updates

Let’s imagine, explore, and uncover the mysteries together!

Let’s imagine, explore, and uncover the mysteries together!