Introduction to Goiânia accident

On September 13, 1987, an unprotected radiation source was taken from an abandoned hospital site in Goiânia, Goiás, Brazil, resulting in the Goiânia disaster [ơojˈjɐniɐ], a radioactive contamination incident. Four individuals died as a result of the several persons who handled it after that. 249 of the approximately 112,000 individuals who were screened for radioactive contamination were determined to be contaminated.

Several homes were demolished and dirt had to be hauled from multiple locations during the ensuing cleanup effort. Every item found in the homes, including private belongings, was confiscated and burned. It was dubbed ‘one of the world’s worst radiation events’ by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and one of the ‘biggest nuclear disasters’ by Time magazine.

An explanation of the source

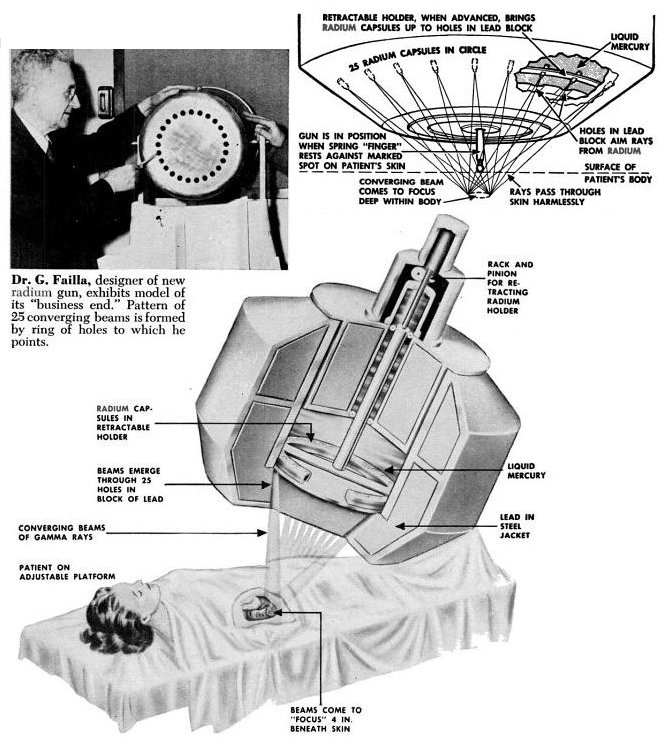

A tiny capsule containing around 93 grams (3.3 oz) of highly radioactive caesium chloride—a caesium salt produced with the radioisotope caesium-137—encased in a lead and steel shielding canister served as the radiation source in the Goiânia disaster. The source was placed inside a wheel-shaped container, which rotates inside the shell to transport the source between the irradiation and storage locations.

In 1971, the source’s activity was 74 terabecquerels (TBq). The container is referred to as a “international standard capsule” by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). It measured 48 mm (1.8 inches) in length and 51 millimeters (2 inches) in diameter. Approximately 814 TBq·kg−1 of caesium-137, an isotope with a half-life of 30 years, was the specific activity of the active solid.

A.) a sealed outer protective casing (usually lead),

B.) a retaining ring, and

C.) a teletherapy “source” (diameter in this diagram is 30 mm), composed in turn of

D.) two nested stainless steel canisters welded to

E.) two stainless steel lids surrounding

F.) a protective internal shield (usually uranium metal or a tungsten alloy), and

G.) a cylinder of radioactive source material (caesium-137 in the Goiânia incident, but usually cobalt-60)

At one meter from the source, the dosage rate was 4.56 grays per hour (456 rad·h−1). The gadget was believed to have been manufactured in the United States at Oak Ridge National Laboratory as a radiation source for radiation treatment at the Goiânia hospital, but the lack of a serial number made it difficult to confirm its identification.

According to the IAEA, about 44 TBq (1,200 Ci) of contamination were recovered throughout the cleanup process, while the source had 1,375 Ci (50.9 TBq) when it was taken. This indicates that 7 TBq (190 Ci) were still present in the environment; by 2016, this would have decomposed to around 95 Ci (3.5 TBq).

Things that Happen

Hospital desertion

One kilometer (0.6 mi) northwest of Praça Cívica, the city’s administrative hub, stood the private radiation facility known as the Instituto Goiano de Radioterapia (IGR). A caesium-137-based teletherapy equipment that IGR had acquired in 1977 was left behind when it relocated to its current location in 1985. IGR and the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul, the property’s previous owner, contested the abandoned site’s destiny in court. The Court of Goiás declared on September 11, 1986, that it was aware of the radioactive material that had been left in the premises.

Four months before the theft, on May 4, 1987, Saura Taniguti, then director of Ipasgo, the institute of insurance for civil servants, used police force to prevent one of the owners of IGR, Carlos Figueiredo Bezerril, from removing the radioactive material that had been left behind. Figueiredo then warned the president of Ipasgo, Lício Teixeira Borges, that he should take responsibility ‘for what would happen with the caesium bomb.’ The Court of Goiás posted a security guard to protect the site.

Meanwhile, the owners of IGR wrote several letters to the National Nuclear Energy Commission (CNEN), warning them about the danger of keeping a teletherapy unit at an abandoned site, but they could not remove the equipment on their own once a court order prevented them from doing so.

The source’s theft

The site’s security guard failed to report for duty on September 13, 1987. Wagner Mota Pereira and Roberto dos Santos Alves broke inside the partially destroyed IGR facility. In order to get the source assembly to Roberto’s house, they partially dismantled the teletherapy unit and put it in a wheelbarrow.

They believed the device could have some scrap value. They started taking the apparatus apart. They both started throwing up that same evening from radiation illness. Pereira’s left hand started to swell the next day, and he started to feel lightheaded and had diarrhea. Later on, he had a burn on his hand that was the same size and form as the hole, and he had to have several of his fingers partially amputated.

Pereira was ordered to go home and relax after being diagnosed with a foodborne disease at a nearby clinic on September 15. Nevertheless, Roberto persisted in his attempts to disassemble the apparatus and ultimately managed to release the caesium capsule from its revolving protecting head. His right forearm developed ulcers as a result of his extended exposure to the radioactive substance, necessitating its amputation on October 14.

Legal matters

The Federal Union, the National Nuclear Energy Commission, the State of Goiás (through its Health Department), the Social Security Institute for Civil Servants in the State of Goiás – IPASGO, which at the time of the accident was the private owner of the land where the IGR was located, the four doctors who owned IGR, the clinic’s physicist, who was also the supervisor, and the Federal Public Prosecution Service (Department of Justice) filed a public civil action for environmental damages in September 1995 with the State of Goiás Public Prosecution Service.

The defendants were ordered to pay R$1.3 million (approximately US$750,000) to the Defense of the Diffused Rights Fund, a federal fund for compensating for damages to consumers, property, the environment, and rights of artistic, historic, or cultural value, among other collective rights, by the 8th Federal Court of Goiás on March 17, 2000.

The judge’s judgment excluded the Federal Union and the state of Goiás from paying compensation.

The CNEN was mandated to provide R$1 million in compensation, ensure medical and psychological care for the accident’s direct and indirect victims as well as their third-generation descendants, transport the most seriously injured victims to medical examinations, and oversee the city of Abadia de Goiás’s medical follow-up.

As of September 13, 1987, when the caesium-137 capsule was removed, the Social Security Institute for Civil Servants in the State of Goiás, or IPASGO, was compelled to pay a fine of R$100,000 plus interest.

The court was unable to hold IGR’s owners accountable since the incidents happened prior to the Federal Constitution of 1988 and the clinic, not the individual owners, purchased the chemical. One of the owners, however, was fined R100,000 for being responsible for the IGR building’s abandoned condition, which included the demolition of the roof, windows, timberwork, and gates in May 1987. This was the structure where the caesium source was housed.

Because he was the technician in charge of overseeing the medical manipulation of the radiological apparatus, the clinic’s physicist was also fined R100,000.

The court’s ruling held the two robbers personally accountable for the accident, despite the fact that they were not named as defendants in the public civil complaint. Since their acts resulted in strict (no-fault) responsibility, they would have undoubtedly been found guilty if they had been arraigned as defendants. In terms of criminal intent, however, they were unaware of the gravity of their actions in removing the caesium source from its location and were not aware of the radiological device’s dangers; additionally, the abandoned clinic had no danger sign installed to deter intruders.

Some Mysteries related to Goiânia accident

1. What was the cause of the Goiânia accident in 1987?

The Goiânia accident, which occurred in 1987, was caused by the mishandling of a radioactive device. The incident began when two scrap metal scavengers unknowingly discovered a cobalt-60 source, a radioactive substance, inside an abandoned radiotherapy unit. The device, left behind in a building that had been poorly secured and neglected, was not properly disposed of, allowing for the radioactive material to be exposed. The scavengers, unaware of the danger, opened the device, and one of them even took a piece of the radioactive material home. This resulted in widespread contamination and exposure, which would eventually lead to the deaths of several individuals.

2. How did the radioactive material spread across the city of Goiânia?

After the scavengers discovered the cobalt-60 capsule, they shared the material with others in the community, thinking it was something valuable or special. The radioactive substance was handled without any knowledge of its lethal properties, and some individuals even spread the glowing blue powder from the device to their friends and families. As more people came into contact with the substance, the radioactive material quickly spread throughout the city. The authorities, unaware of the contamination at first, struggled to control the situation as the contamination affected multiple locations in Goiânia. The entire event led to a significant public health and environmental crisis that would continue for years.

3. Why wasn’t the radioactive material properly secured or disposed of?

The failure to properly secure and dispose of the radioactive material can be attributed to a combination of factors, including neglect, lack of proper oversight, and bureaucratic inefficiency. The radiotherapy unit from which the cobalt-60 source came was abandoned years before the accident, and the building had not been adequately secured. At the time, there was little regulation surrounding the disposal of radioactive material in Brazil, and the safety protocols that would have prevented the mishandling of such material were not strictly enforced. This regulatory and operational failure created an environment where a potentially dangerous substance was left in an accessible, unsecured location.

4. What role did local authorities play in preventing the spread of contamination?

Local authorities in Goiânia struggled to contain the situation once the scope of the accident became clear. Initially, they were unaware of the gravity of the radioactive exposure and mistakenly thought it was a conventional case of theft or criminal activity. As more individuals started to display symptoms of radiation sickness, the authorities were forced to call in radiation experts from other parts of the country. However, by the time the government fully understood the scale of the contamination, many people had already been exposed, and the radioactive material had spread to numerous locations across the city. The lack of proper training and resources made it difficult for local authorities to manage the situation effectively in the early stages.

5. What were the health effects on the individuals exposed to the radioactive material?

The health effects on the individuals exposed to cobalt-60 were severe and tragic. The first symptoms of radiation sickness included nausea, vomiting, and severe burns, which were soon followed by hair loss and other signs of radiation poisoning. Several individuals who had come into direct contact with the radioactive material or who had been exposed to it for extended periods developed more severe health conditions. Some died from radiation exposure within weeks, while others suffered from long-term health problems, including cancers and other complications that could take years to manifest. Overall, 4 people lost their lives directly due to the radiation exposure, and many more were affected by the toxic substance.

6. How did the accident in Goiânia impact the global understanding of radiation safety?

The Goiânia accident raised global awareness about the dangers of radiation exposure and the need for stricter safety regulations regarding the use and disposal of radioactive materials. The incident highlighted serious deficiencies in the handling and oversight of radioactive sources, especially in developing countries. In the aftermath of the disaster, international organizations such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) began advocating for stronger measures to prevent similar accidents. The Goiânia accident served as a wake-up call for many countries to reevaluate their own safety standards and to implement more rigorous procedures for managing radioactive waste and materials.

7. Why was the public initially unaware of the seriousness of the radioactive contamination?

In the early stages of the Goiânia accident, the public was largely unaware of the radioactive contamination because the local authorities did not fully grasp the gravity of the situation. As the authorities were slow to recognize the potential dangers of radiation, people were not immediately informed about the risks associated with the glowing substance they had come into contact with. Some residents even treated the glowing powder as a curiosity, believing it to be something valuable or unusual, which exacerbated the spread of contamination. It wasn’t until radiation experts were brought in that the full extent of the contamination and the associated health risks were revealed to the public.

8. What role did the media play in the aftermath of the Goiânia accident?

The media played a crucial role in spreading awareness about the Goiânia accident, although its role was not without controversy. In the early stages of the event, the media covered the story, but there was a lack of clarity in the way the situation was portrayed.

Initially, the reports focused on the theft of a mysterious object and the potential criminal elements involved, without emphasizing the radioactive nature of the material. Once the scale of the contamination became clearer, the media helped spread the necessary warnings to the public about the dangers of radiation exposure. However, sensationalized reporting also created confusion and fear among residents, making it more difficult for authorities to manage the crisis in a calm and effective manner.

9. How were the individuals involved in the Goiânia accident treated by health officials?

The individuals who were exposed to the radioactive material in Goiânia were treated with varying levels of care, depending on the severity of their exposure. Once the authorities and health officials realized the contamination’s scope, they took immediate action to isolate and treat those most affected by radiation sickness. Several people received medical treatment, including radiation decontamination and other forms of supportive care, to mitigate the effects of radiation exposure. However, many of those who had been exposed faced long-term health challenges and were closely monitored for any emerging signs of illness. Due to the lack of expertise at the time, the treatment methods used were not always effective, and some individuals were left without proper care.

10. What were the long-term consequences of the Goiânia accident for the local community?

The long-term consequences of the Goiânia accident were profound, affecting both the physical and social aspects of the community. In the years following the event, many survivors suffered from chronic health problems, including cancers and other radiation-related diseases, which were directly linked to their exposure to cobalt-60. The city also faced a significant economic burden, as large areas had to be decontaminated and abandoned, causing disruptions to local businesses and residents.

Socially, the incident left a lasting impact on the community’s trust in local authorities and their ability to ensure public safety. The Goiânia accident also led to widespread changes in Brazil’s laws surrounding the use and disposal of radioactive materials, as well as greater international attention to radiation safety and waste management.

Latest Updates

Let’s imagine, explore, and uncover the mysteries together!

Let’s imagine, explore, and uncover the mysteries together!