Part:-1

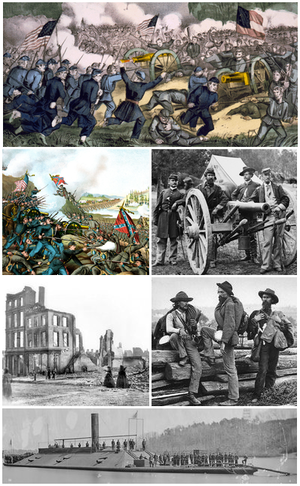

The American Civil War, which took place from April 12, 1861, to May 26, 1865, was a defining moment in U.S. history. It was a brutal conflict between the Union, representing the North, and the Confederacy, formed by Southern states that had seceded. The key issue driving the war was the question of whether slavery would be allowed to expand into new territories, a debate that had divided the nation for decades. Many believed that if slavery were kept from spreading, it would eventually die out.

The situation came to a head in 1860 when Abraham Lincoln, who opposed the expansion of slavery, was elected president. In response, seven Southern slave states broke away from the Union, forming the Confederacy. They seized U.S. forts and other federal property within their borders, and on April 12, 1861, the Confederates fired the first shots of the war at Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

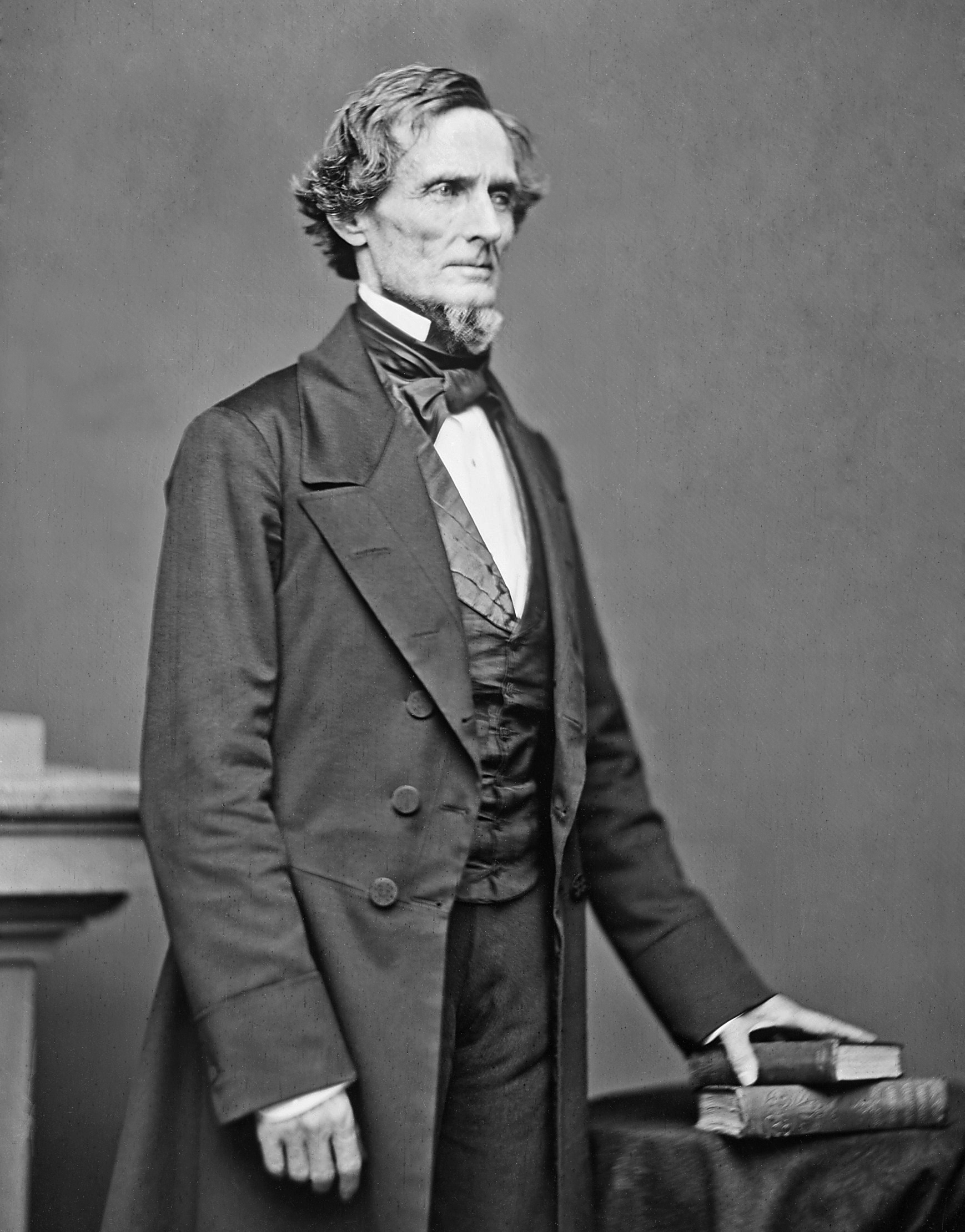

Both sides were swept up in a wave of enthusiasm, and thousands of men joined the military as the war began. Soon after, four more Southern states joined the Confederacy, with Jefferson Davis leading them as president. At its height, the Confederacy controlled about a third of the U.S. population across eleven states.

The war was long and bloody, with most of the fighting taking place in the South. In the Western part of the conflict, the Union made important gains, but the fighting in the East was less decisive. The abolition of slavery became a major goal for the Union after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. This document declared that slaves in the Confederate states were free, impacting over 3.5 million enslaved people.

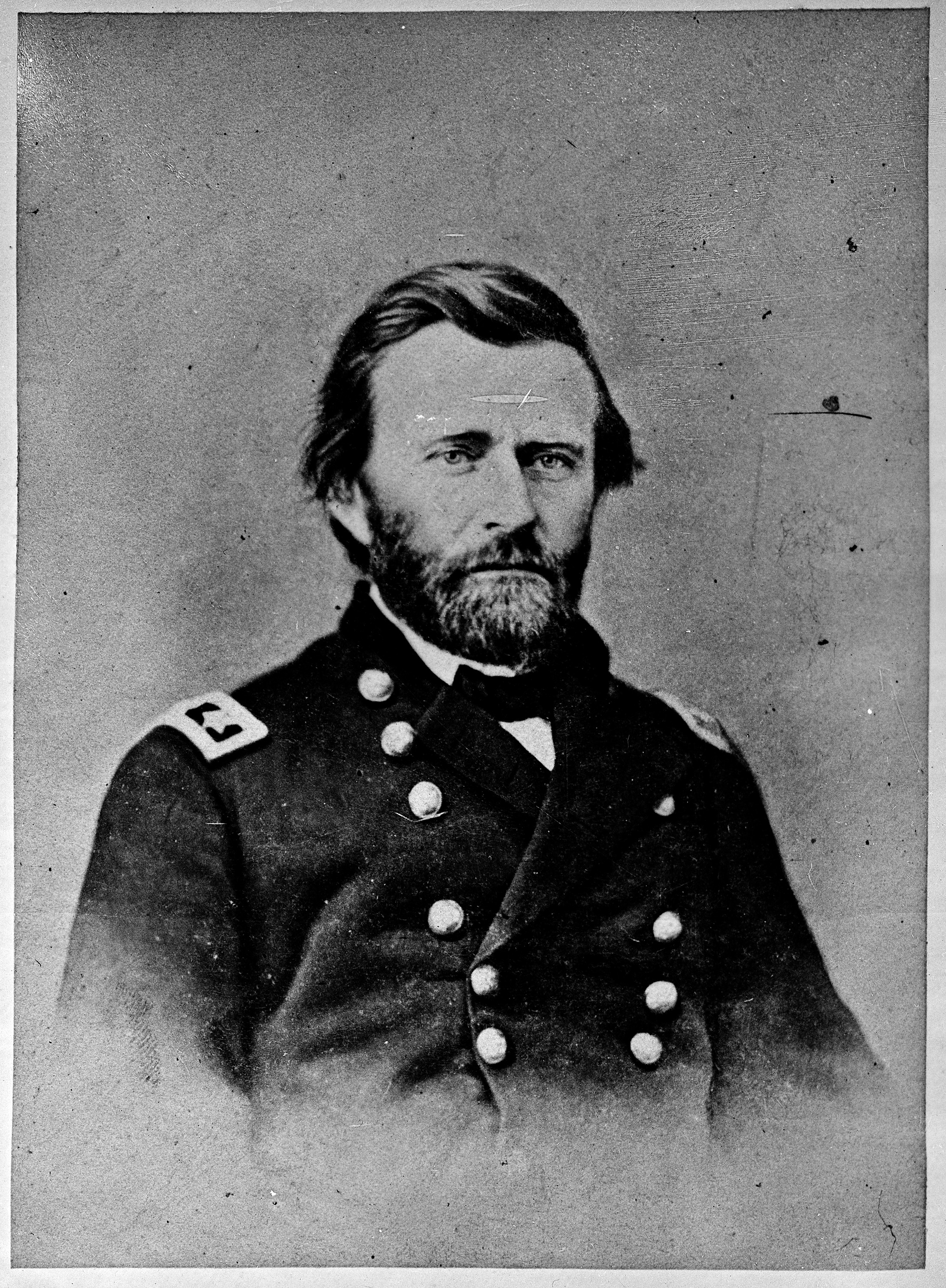

The Union also made progress in the West by defeating the Confederacy’s river navy and capturing key cities like New Orleans. The 1863 siege of Vicksburg was a turning point, splitting the Confederacy along the Mississippi River. At the same time, Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s attempt to invade the North ended in failure at the Battle of Gettysburg. These victories helped bring General Ulysses S. Grant to the leadership of all Union forces by 1864.

With a naval blockade choking Confederate ports and Union forces advancing on all fronts, the Confederacy began to collapse. The capture of Atlanta by General William Tecumseh Sherman in 1864, followed by his infamous March to the Sea, further weakened the South. The final major battle occurred during the Siege of Petersburg, which was the gateway to the Confederate capital of Richmond.

The Confederates eventually abandoned Richmond, and on April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, signaling the end of the war. Tragically, President Lincoln was assassinated just days later, on April 14, and died the following day.

By the war’s end, much of the South was in ruins. The Confederacy was defeated, slavery was abolished, and four million formerly enslaved people were freed. The country then entered the Reconstruction era, an effort to rebuild the nation, reintegrate the Southern states, and grant civil rights to the newly freed African Americans. The Civil War remains one of the most studied periods in U.S. history and continues to be the subject of much debate, especially regarding the legacy of the Confederacy.

It was one of the first wars to use modern technologies like railroads, the telegraph, steam-powered ships, and mass-produced weapons. The war claimed the lives of between 620,000 and 750,000 soldiers, making it the deadliest conflict in American history. The horrors of the Civil War foreshadowed the industrial-scale warfare that would later dominate the World Wars.

Origins

Most historians agree that the main reason the eleven Southern states (seven before the war, four after it started) seceded from the Union to form the Confederacy was to preserve slavery. Although historians today widely recognize slavery as the key issue, they still debate which aspects of the conflict—whether ideological, economic, political, or social—were most important in shaping the war.

There’s also disagreement about why the North refused to let the Southern states leave the Union. However, a revisionist view known as the “Lost Cause” has tried to argue that slavery wasn’t the main reason for secession. This view has been thoroughly disproven, especially by the secession documents of several Confederate states, which clearly show slavery as their primary motive.

The main political battle that led to Southern secession revolved around whether slavery should expand into the Western territories, which were expected to become new states. For years, Congress had maintained a balance between free and slave states by admitting them in pairs—one free and one slave. While this balance worked in the Senate, it didn’t hold in the House of Representatives, where free states eventually outnumbered slave states.

By the mid-1800s, the status of these new territories became a critical issue. The North was increasingly anti-slavery, while the South feared the eventual end of slavery. In addition to the issue of slavery, a growing sense of Southern nationalism also contributed to the decision to secede.

For the North, the primary reason to oppose secession was the desire to preserve the Union. This was rooted in a strong sense of American nationalism. Other background factors leading to the war included partisan politics, the rise of abolitionism, debates over states’ rights and secession, as well as differences in the economic and social systems of the North and South. A group of historians in 2011 emphasized that while slavery was the main cause of the Southern states’ decision to leave the Union, it was the act of secession itself that triggered the war.

As historian David M. Potter noted, the conflict for Northerners wasn’t just about freeing slaves. They also faced a dilemma: they wanted to honor the Constitution, which protected slavery, while also preserving the Union, which meant maintaining a relationship with slaveholders. These conflicting values could not be easily reconciled, which made the situation even more complex.

Lincoln’s election

The election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860 was the tipping point that led to Southern secession. Southern leaders were deeply concerned that Lincoln would halt the expansion of slavery, setting it on a path toward eventual extinction. Although Lincoln wouldn’t officially take office until March 4, 1861, this gave the Southern states time to secede and begin preparing for war during the winter of 1860–1861.

According to Abraham Lincoln, the American people had already proven they were capable of creating and governing a republic. However, the nation now faced a new and significant challenge: the need to preserve a republic founded on the will of the people, especially in the face of efforts to dismantle it. This was the critical test that the nation confronted during the Civil War.

Outbreak of the war

Secession crisis

Lincoln’s election led South Carolina’s legislature to convene a state convention to discuss secession. South Carolina had long been a strong advocate for the idea that a state had the right to nullify federal laws and even secede from the Union. On December 20, 1860, the convention voted unanimously to secede and adopted a formal declaration.

This declaration defended states’ rights, particularly the rights of slave owners, but it also criticized Northern states for not enforcing the federal Fugitive Slave Act, accusing them of failing to return escaped slaves. Following South Carolina’s lead, the “cotton states” of Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas also seceded in January and February of 1861.

In their ordinances of secession, Texas, Alabama, and Virginia specifically mentioned the hardships faced by “slaveholding states” due to Northern abolitionists. The other states issued short statements declaring their departure from the Union without directly mentioning slavery.

However, four states—South Carolina, Mississippi, Georgia, and Texas—provided detailed reasons for seceding, with all of them pointing to the abolitionist movement and its growing influence in the North as the primary cause. The Southern states believed the Fugitive Slave Clause in the Constitution guaranteed their right to own slaves, and they saw Northern resistance to this as a violation of their rights.

On February 4, 1861, these states agreed to form a new government, the Confederate States of America. They quickly took control of federal forts and properties within their borders with little opposition from outgoing President James Buchanan. Although Buchanan believed that the Southern states had no legitimate reason to secede, citing the Dred Scott decision as evidence that slavery was constitutionally protected, he also argued that the federal government had no constitutional authority to force a state to remain in the Union by military action. Meanwhile, in February 1861, a quarter of the U.S. Army—stationed in Texas—was surrendered to state forces by General David E. Twiggs, who then joined the Confederacy.

As Southern lawmakers resigned from their seats in the Senate and House, Republicans were able to push through several major initiatives that had previously been blocked. These included the Morrill Tariff, which raised duties on imports, the establishment of land grant colleges, the passage of the Homestead Act, which gave settlers land in the West, and the authorization of a transcontinental railroad.

The National Bank Act was also passed, along with the Legal Tender Act of 1862, which allowed the government to issue paper currency (United States Notes). Additionally, slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia. To help finance the war, the Revenue Act of 1861 introduced the first federal income tax.

In December 1860, the Crittenden Compromise was proposed as a way to prevent secession by re-establishing the Missouri Compromise line. It would have constitutionally banned slavery in territories north of the line while allowing it to continue in territories to the south. While this compromise could have possibly stopped secession, Lincoln and the Republicans rejected it, with Lincoln arguing that any compromise extending slavery would ultimately destroy the Union.

In February, a peace conference was held in Washington, where a similar solution was proposed, but it was also rejected by Congress. Instead, the Republicans offered the Corwin Amendment, which promised not to interfere with slavery where it already existed, but the Southern states saw this as inadequate. Despite these efforts, eight remaining slave states chose not to join the Confederacy, with Virginia’s First Secessionist Convention voting against secession on April 4, 1861.

On March 4, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as president. In his inaugural address, he argued that the Constitution created a stronger and more unified nation than the earlier Articles of Confederation, and he declared that secession was “legally void.” Lincoln made it clear that he had no intention of invading the Southern states or ending slavery where it already existed.

However, he emphasized that he would use force if necessary to retain control of federal property, including forts, arsenals, mints, and customhouses that had been taken by the Confederacy. He noted that the government would not attempt to recover post offices and that mail delivery would stop at state borders if met with resistance. In areas where federal law couldn’t be enforced peacefully, U.S. marshals and judges would be withdrawn.

Lincoln did not address the loss of bullion from Southern mints but did stress that the U.S. government would continue to collect duties and taxes. He reassured that there would be no invasion or use of force unless absolutely necessary, and he urged for peace and the restoration of the Union. His speech concluded with an emotional appeal to reunite the country, invoking “the mystic chords of memory” that tied the North and South together.

The newly formed Confederate government, led by Jefferson Davis, sent representatives to Washington in hopes of negotiating a peace treaty. However, Lincoln refused to negotiate with them, arguing that the Confederacy was not a legitimate government, and that making a treaty would imply recognition of it as such. Instead, Lincoln tried to negotiate directly with the governors of the seceded states, as he still considered their administrations to be lawful.

Lincoln’s efforts to resolve the crisis were complicated by his Secretary of State, William H. Seward. Seward had been Lincoln’s main rival for the Republican presidential nomination, and though he agreed to support Lincoln’s candidacy, it was only after securing a prominent position in the administration.

Early in Lincoln’s presidency, Seward underestimated Lincoln, seeing him as inexperienced and viewing himself as the real power behind the scenes, almost like a “prime minister.” Seward attempted unauthorized backdoor negotiations, which ultimately failed.

Meanwhile, Lincoln was resolute in his decision to hold on to the Union-controlled forts still within Confederate territory. These included Fort Monroe in Virginia, Fort Pickens, Fort Jefferson, and Fort Taylor in Florida, and most crucially, Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

Battle of Fort Sumter

The American Civil War officially began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces fired upon Fort Sumter, which was held by Union troops in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. The status of Fort Sumter had been a point of contention for several months.

Outgoing President Buchanan had hesitated to reinforce its garrison, which was commanded by Major Robert Anderson. Taking matters into his own hands, Anderson moved his troops under the cover of darkness on December 26, 1860, from the poorly positioned Fort Moultrie to the more defensible Fort Sumter. This bold move elevated Anderson to hero status in the North.

An attempt to resupply the fort on January 9, 1861, nearly sparked a war, but an informal truce managed to hold for a time. By March 5, Lincoln was informed that Fort Sumter was running low on supplies, setting the stage for the conflict that was about to erupt.

Fort Sumter presented a significant challenge for Lincoln’s administration. Back-channel negotiations by Secretary of State Seward with the Confederates complicated Lincoln’s decision-making, as Seward favored withdrawing from the fort. However, Lincoln maintained a firm hand, ensuring that Seward remained a staunch ally.

Ultimately, Lincoln determined that holding Fort Sumter and reinforcing it was the only viable option. On April 6, he informed the Governor of South Carolina that a ship carrying food, but no ammunition, would attempt to resupply the fort.

Historian James McPherson describes this strategy as “the first sign of the mastery that would mark Lincoln’s presidency.” The plan allowed for a win-win scenario: if the Union successfully resupplied and held the fort, it would be a victory; if the Confederacy attacked an unarmed supply ship meant for starving troops, they would be seen as the aggressors.

At a Confederate cabinet meeting on April 9, President Davis ordered General P. G. T. Beauregard to take Fort Sumter before the supplies could reach it, setting the stage for the impending conflict.

At 4:30 a.m. on April 12, Confederate forces fired the first of 4,000 shells at Fort Sumter, which ultimately fell the following day. The loss of Fort Sumter ignited a surge of patriotism in the North. On April 15, Lincoln called on the states to supply 75,000 volunteer troops for a period of 90 days, and the eager Union states quickly met this call.

On May 3, 1861, Lincoln requested an additional 42,000 volunteers for a three-year commitment. In the wake of these developments, Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina seceded from the Union and joined the Confederacy. To honor Virginia’s new status, the Confederate capital was relocated to Richmond.

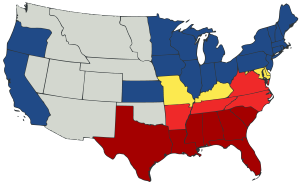

Attitude of the border states

Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, West Virginia, and Kentucky were slave states with populations that had divided loyalties between Northern and Southern interests, as well as family ties. As a result, some men from these states enlisted in the Union Army, while others joined the Confederate Army.

West Virginia, in particular, separated from Virginia during the war and was admitted to the Union on June 20, 1863, despite the fact that half of its counties had secessionist sentiments.

Maryland’s territory completely surrounded Washington, D.C., posing a threat that it could cut off the capital from the North. The state had anti-Lincoln officials who allowed anti-army riots to occur in Baltimore, along with acts of sabotage such as burning bridges, all aimed at obstructing the movement of Union troops toward the South. Although Maryland’s legislature voted overwhelmingly to remain in the Union, it also sought to avoid hostilities with its Southern neighbors, even deciding to close the state’s rail lines to prevent their use in the war.

In response, Lincoln established martial law in Maryland and suspended habeas corpus, asserting control over the situation. He sent militia units into the state and took drastic measures by arresting prominent figures, including one-third of the members of the Maryland General Assembly on the very day they reconvened.

All those arrested were held without trial, and Lincoln disregarded a ruling from Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney, who stated that only Congress had the authority to suspend habeas corpus in the case of Ex parte Merryman. Additionally, federal troops imprisoned a Baltimore newspaper editor, Frank Key Howard, after he published an editorial criticizing Lincoln for ignoring Taney’s ruling.

In Missouri, an elected convention on secession decided to stay with the Union. However, when pro-Confederate Governor Claiborne F. Jackson called out the state militia, federal forces under General Nathaniel Lyon attacked. Lyon pursued the governor and the State Guard all the way to the southwestern corner of Missouri.

At the beginning of the war, the Confederacy managed to gain control over southern Missouri through a Confederate government. However, they were driven out of the area after 1862. Following this defeat, the secession convention reconvened and established itself as the Unionist provisional government of Missouri.

Kentucky initially declared itself neutral and chose not to secede from the Union. However, when Confederate forces entered the state in September 1861, this neutrality came to an end, and Kentucky reaffirmed its loyalty to the Union while still allowing slavery to continue.

During the Confederate invasion in 1861, sympathizers in Kentucky and delegates from 68 counties convened the Russellville Convention, where they formed a shadow government known as the Confederate Government of Kentucky. They inaugurated their own governor and Kentucky was admitted into the Confederacy on December 10, 1861.

However, this Confederate government had jurisdiction only over the areas of Kentucky that were under Confederate control, which at its peak covered more than half the state. The government eventually went into exile after October 1862 as Union forces regained control.

War

Battles were fierce and frequent during the Civil War. Along with several lesser operations, 237 designated battles were fought over the course of four years; they were frequently distinguished by their high fatalities and harsh ferocity. According to historian John Keegan, it was “one of the most ferocious wars ever fought,” with the enemy’s men sometimes the main target.

Prisoners

A parole system was in place at the beginning of the conflict, whereby prisoners consented to refrain from fighting until they were swapped. They were paid and housed in army-run camps, but they were prohibited from engaging in any military activities. When the Confederacy refused to trade black captives in 1863, the exchange system fell apart. After that, over 56,000 of the 409,000 prisoners of war—or 10% of the total deaths during the conflict—died in jail.

Women

Between 500 and 1,000 women enrolled as troops on both sides, posing as males, according to historian Elizabeth D. Leonard.[90] In addition, women worked as nurses, medical staff, resistance activists, and spies. In addition to nursing Union and Confederate soldiers at field hospitals, women worked aboard the Union hospital ship Red Rover. The first woman to ever win the Medal of Honor, Mary Edwards Walker, was awarded the award for her efforts to care the war’s wounded while serving in the Union Army. As Albert D. J. Cashier, one lady, Jennie Hodgers, fought for the Union. She went on to live as a man once she returned to civilian life, passing away in 1915 at the age of 71.

By 1865, the little U.S. Navy of 1861 had grown to 45,000 sailors and 6,000 officers, with 671 ships weighing 510,396 tons. Its objectives were to control the river system, blockade Confederate ports, protect the high seas from Confederate raids, and prepare for a potential conflict with the British Royal Navy. The Confederate heartland was accessible by major rivers in the West, where the primary riverine combat was fought. The Red, Tennessee, Cumberland, Mississippi, and Ohio rivers were eventually under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Navy. The Navy assisted army operations along the coast and bombarded Confederate forts in the East.

Early in the Industrial Revolution, the Civil War led to naval advancements, most notably the ironclad vessel. The Confederacy constructed or modified more than 130 ships, including 26 ironclads, in order to challenge the Union’s naval strength. Confederate ships mostly failed to defeat Union ironclads in spite of their attempts. Timberclads, tinclads, and armored gunboats were all employed by the Union Navy. Steamboats were constructed or altered in shipyards in Cairo, Illinois, and St. Louis.

The Confederacy tried with the submersible CSS Hunley, which was not successful, and with the ironclad CSS Virginia, constructed from the sinking Union ship Merrimack. Virginia severely damaged the Union’s wooden fleet on March 8, 1862, but the USS Monitor, the first Union ironclad, arrived the next day to confront it in the Chesapeake Bay.

Ironclads proved to be successful vessels in the next three-hour Battle of Hampton Roads, which ended in a draw. While the Union constructed several replicas of the Monitor, the Confederacy destroyed the Virginia to avoid its capture.

Great Britain had little interest in supplying warships to a country at war with a more powerful adversary and was afraid of deteriorating ties with the United States, therefore the Confederacy’s attempts to acquire warships from them failed.

Union blockade

In order to win the war with the least amount of carnage possible, General Winfield Scott came up with the Anaconda Plan in early 1861. This plan called for a blockade of the Confederacy in order to force the South to submit. Lincoln chose a more aggressive military strategy, but he did embrace some of the plan. Lincoln declared a blockade of all Southern ports in April 1861, which prevented commercial ships from obtaining insurance and put a halt to normal business.

It was too late when the South made the mistake of stopping cotton shipments before the blockade was completely in place. The South’s ability to export less than 10% of its cotton meant that “King Cotton” was no more. The eight Confederate seaports with railheads that transported nearly all of the cotton were closed by the blockade. Warships were positioned off the main ports in the South by June 1861, and by the following year, around 300 ships were operational.

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the main Confederate army in the Eastern theater. The Army was first established on June 20, 1861, as the (Confederate) Army of the Potomac, which was composed of all Northern Virginia operational troops. Forces from the District of Harpers Ferry and the Army of the Shenandoah were added on July 20 and 21. Between March 14 and May 17, 1862, Army of the Northwest units were combined into the Army of the Potomac. On March 14, the Army of the Potomac changed its name to the Army of Northern Virginia. On April 12, 1862, it was combined with the Army of the Peninsula.

Despite his wish for the nation to be united and the offer of a senior Union command, Robert E. Lee decided to join his home state when Virginia announced its secession in April 1861. According to Douglas S. Freeman, Lee’s biographer, when he issued orders assuming command on June 1, 1862, Lee gave the army its ultimate name. Freeman acknowledges, however, that prior to that date, Lee had written to his predecessor in army leadership, Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston, referring to Johnston’s command as the Army of Northern Virginia.

The fact that Johnston was the commander of the Department of Northern Virginia (as of October 22, 1861), and that the term Army of Northern Virginia is an unofficial byproduct of the name of its parent department, contributes to some of the misunderstanding. Even though it is only accurate in hindsight, the Army of Northern Virginia is the term that is often used today, even though Jefferson Davis and Johnston did not use it. This is because it is evident that the forces organized as of March 14 were the same ones that Lee received on June 1.

Colonel Thomas J. Jackson put Jeb Stuart in charge of all the Army of the Shenandoah’s cavalry troops on July 4 at Harper’s Ferry. Eventually, he became the cavalry commander of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Western theater

Army of the Tennessee and Army of the Cumberland

The Army of the Tennessee and the Army of the Cumberland, which were called after the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, were the main Union forces in this area. Lincoln looked for fresh leadership in the Western theater following Meade’s unsuccessful fall campaign. Lincoln needed a new commander, and Ulysses S. Grant was born when the Confederate fortress of Vicksburg surrendered, giving the Union control of the Mississippi River and permanently isolating the western Confederacy.

Army of Tennessee

The Army of Tennessee was the main Confederate army in the Western theater. General Braxton Bragg renamed the previous Army of Mississippi to create the new army on November 20, 1862. The Confederate armies were repeatedly beaten in the West, despite their victories in the Eastern theater.

Trans-Mississippi theater

Battles

The Battle of Wilson’s Creek (August 1861) was the first conflict in the Trans-Mississippi theater. Early in the war, the Battle of Pea Ridge forced the Confederates out of Missouri.

The trans-Mississippi area was characterized by intense guerrilla warfare because the Confederacy lacked the manpower and supplies to sustain conventional forces that would threaten Union authority. Confederate gangs like Quantrill’s Raiders terrified the countryside by attacking both civilian villages and military posts. The “Order of the American Knights” and “Sons of Liberty” attacked unarmed uniformed troops, government officials, and pro-Union citizens. It took the engagement of a whole regular Union army division to force these partisans out of Missouri. These violent actions hurt the national antiwar movement that was planning to oppose Lincoln’s reelection in 1864. In addition to keeping Missouri in the Union, Lincoln won reelection with 70% of the vote.

The Union attempted to seize control of Indian Territory and New Mexico Territory with small-scale military operations west and south of Missouri. The New Mexico Campaign’s pivotal conflict was the Battle of Glorieta Pass. In 1862, the exiled government of Arizona fled into Texas after the Union drove Confederate raids into New Mexico. Tribal civil wars erupted in the Indian Territory. Fewer Indian warriors served for the Union than the roughly 12,000 who fought for the Confederacy. Brigadier Commander Stand Watie, the final Confederate commander to surrender, was the most well-known Cherokee.

General Kirby Smith in Texas was told by Jefferson Davis that he could not anticipate any more assistance from east of the Mississippi following the surrender of Vicksburg in July 1863. Despite having insufficient resources to defeat Union forces, he established a strong arsenal at Tyler and his own Kirby Smithdom economy, a fictitious “independent fiefdom” in Texas that included international smuggling and railroad building. He was not immediately confronted by the Union. Texas stayed in Confederate hands throughout the war until its unsuccessful Red River Campaign in 1864 to capture Shreveport, Louisiana.

Conquest of Virginia

Lincoln appointed Grant commander of the Union troops at the start of 1864. Major General William Tecumseh Sherman commanded the majority of the western army when Grant established his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac. Like Lincoln and Sherman, Grant recognized the idea of total war and thought that the war would only be over when the Confederate soldiers and their economy were completely destroyed. According to Grant, this was a complete war that “would otherwise have gone to the support of secession and rebellion” because it destroyed houses, farms, railroads, and supplies and fodder, not because it killed people. I think this strategy had a significant impact on speeding up the conclusion.

Grant came up with a well-planned plan that would attack the Confederacy as a whole from several angles. General Sherman was to take Atlanta and march to the Atlantic Ocean, Generals George Crook and William W. Averell were to operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks was to seize Mobile, Alabama, General Franz Sigel was to attack the Shenandoah Valley, and Generals Meade and Benjamin Butler were to move against Lee near Richmond.

Thank you for your patience! Part two will be uploaded soon.