On November 24, 1971, an unnamed individual going by the name of D. B. Cooper, also known as Dan Cooper, took control of Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305, a Boeing 727, inside US airspace. The hijacker informed a flight attendant that he had a bomb during the journey from Portland, Oregon to Seattle, Washington.

He also wanted a ransom of $200,000, which would be around $1,500,000 in 2024, and four parachutes upon arrival in Seattle. The hijacker told the flight crew to refuel the plane and take off again toward Mexico City, stopping in Reno, Nevada, after releasing the passengers in Seattle.

The hijacker exited the aircraft through the aft door, lowered the stairway, and parachuted into the darkness over southwest Washington, some thirty minutes after the flight took off from Seattle.

When the hijacker purchased his one-way ticket in Portland, Oregon, he gave his identity as Dan Cooper. However, a reporter mistook his name for that of another suspect, so the hijacker went by “D. B. Cooper” instead.

A tiny amount of the ransom money was discovered in 1980 close to Vancouver, Washington, on the banks of the Columbia River. The money’s finding rekindled popular curiosity in the mystery, but it provided no fresh details on the identity or whereabouts of the hijacker and the money that remained was never found.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) conducted a thorough investigation and compiled a large case file for 45 years following the hijacking, but eventually came to no firm findings. The incident is still the only instance of air piracy in commercial aviation history that has not been solved.

The FBI surmises that Cooper did not make it through his jump for a number of reasons, including the bad weather that night of the hijacking, Cooper’s inappropriate attire and lack of equipment for skydiving, the area that was primarily covered in trees when he jumped, his apparent lack of knowledge about his landing spot, and the disappearance of the money that was left over from the ransom, which suggests it was never used.

Although several ideas on the identity, success, and fate of Cooper are still being pursued by reporters, enthusiasts, professional detectives, and amateur sleuths, the FBI officially halted the ongoing investigation into the NORJAK (Northwest hijacking) case in July 2016.

Major improvements to airport and commercial aviation security protocols were sparked by Cooper’s hijacking and other copies that followed over the course of the next year. Airports were outfitted with metal detectors, luggage checks became required, and travelers who purchased their tickets in cash on the day of departure were singled out for closer examination.

The “Cooper vanes” were installed on Boeing 727s when they were modified. Their main function was to stop the aft stairway from being lowered while the plane was in flight. The number of airplane hijacking occurrences had dropped by 1973 as a result of the new security measures that turned away would-be hijackers with financial gain in mind.

Hijacking

Thanksgiving Eve, November 24, 1971, saw a guy approaching Northwest Orient Airlines’ flight counter at Portland International Airport with a black attaché bag. The man paid with cash for a one-way ticket on Flight 305, which traveled north for thirty minutes to “Sea-Tac” (Seattle–Tacoma International Airport).

The man’s name was “Dan Cooper” on his ticket. According to eyewitnesses, Cooper was a Caucasian man in his mid-40s with brown eyes and dark hair. He was dressed in a business suit of either black or brown, a white shirt, a thin black tie, a black raincoat, and brown shoes. Carrying a brown paper bag and a briefcase, Cooper stepped onto Boeing 727-100 Flight 305 (registration N467US) operated by the FAA.

The flight attendant brought Cooper a drink, a bourbon and 7-Up, and he settled into seat 18-E in the back row.

| N467US, the aircraft involved in the hijacking | |

| Hijacking | |

|---|---|

| Date | November 24, 1971 |

| Summary | Hijacking |

| Site | Between Portland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 727-51 |

| Operator | Northwest Orient Airlines |

| Registration | N467US |

| Flight origin | Portland International Airport |

| Destination | Flight Origin |

| Occupants | 42 |

| Passengers | 36 (including hijacker) |

| Crew | 6 |

| Fatalities | 0 |

| Missing | 1 |

| Survivors | 41 |

Flight 305, carrying 36 passengers, including the hijacker, departed Portland on time at 2:50 PM PST. The crew consisted of six people: Captain William A. Scott, First Officer William “Bill” J. Rataczak, Flight Engineer Harold E. Anderson, and flight attendants Alice Hancock, Tina Mucklow, and Florence Schaffner.

Cooper gave a message to flight attendant Schaffner, who was seated in the jump seat in the back of the aircraft, just behind Cooper, shortly after takeoff. Schaffner put the letter, unsealed, into her handbag, assuming it held the phone number of a lonely businessman. Then Cooper leaned in her direction and said, “Miss, you really should take a look at that note.” I own a bomb.”

Schaffner took the note open. “Miss—I have a bomb in my briefcase and want you to sit by me,” Cooper had written in clean, capital letters printed with a felt-tip pen. Schaffner gave Cooper back the message, sat down at his request, and asked to inspect the explosives in private. She thought the two rows of four crimson cylinders she saw when he opened his bag were explosives. There was a cable and a big, cylindrical battery that looked like bombs attached to the cylinders.

Shutting the suitcase, Cooper informed Schaffner of his requirements. She composed a letter outlining Cooper’s requirements, carried it into the cockpit, and briefed the flight crew on the circumstances. For the duration of the trip, Captain Scott instructed her to stay in the cockpit and record events as they transpired.

He then sent the hijacker’s demands to Northwest Flight Operations in Minnesota, saying, “[Cooper] wants $200,000 in a rucksack by 5:00 pm. Two front and two back parachutes are what he desires.

He requests the funds in US dollars that are negotiable.” Cooper’s request for two sets of parachutes suggested that he intended to bring a captive along, which would have discouraged officials from providing defective gear.

As a point of contact between Cooper and the flight crew in the cockpit, flight attendant Mucklow sat beside Schaffner in the cockpit. He then demanded that all of the passengers stay seated as she carried the money aboard and that the fuel trucks meet the jet when it lands in Seattle. Once he received the money, he promised to release the travelers. The four parachutes would be the final things to be brought on board.

Captain Scott reported the issue to Air Traffic Control (ATC) at Seattle-Tacoma Airport, and ATC then notified the FBI and local law enforcement. The passengers were informed that there would be a “minor mechanical difficulty” causing them to be late arriving in Seattle.

Northwest Orient president Donald Nyrop gave the go-ahead for the ransom to be paid and gave orders to all staff members to assist the hijacker and abide by his demands. In order to give Seattle police and the FBI enough time to gather Cooper’s ransom money and parachutes and to deploy emergency workers, Flight 305 circled Puget Sound for almost two hours.

On the plane ride from Portland to Seattle, Cooper insisted that Mucklow sit beside him the whole time. He seemed to know the area well, she claimed later; he looked out the window and commented, “Looks like Tacoma down there,” as the plane passed over it.

He accurately remarked that McChord Air Force Base was only a 20-minute drive from Seattle-Tacoma Airport when he was informed that the parachutes were coming from there. Later on, she explained the hijacker’s behavior, saying, “[Cooper] was not nervous.” He didn’t seem to be harsh or hostile, and he seemed really polite.”

Mucklow spoke with Cooper while the aircraft circled Seattle, inquiring as to why the hijacker had selected Northwest Airlines. “It’s not because I have a grudge against your airlines, it’s just because I have a grudge,” he said with a giggle, adding that this flight was precisely what he needed.

When he inquired about her origins, she revealed that she was originally from Pennsylvania but was at the moment residing in Minneapolis. In response, Cooper called Minnesota “very nice country.”

When she inquired about his origins, he grew agitated and wouldn’t respond. He gave her a cigarette and inquired as to whether she smoked. Accepting the cigarette, she said that she had given up.

FBI files mention As the aircraft continued its holding pattern over Seattle, Cooper had a brief conversation with an unnamed passenger. Passenger George Labissoniere told FBI officials during his interrogation that he frequently used the lavatory just behind Cooper.

After one trip, Labissoniere questioned Mucklow about the alleged technical issue holding them back, claiming that a passenger with a cowboy hat was obstructing his way to his seat. According to Labissoniere, Cooper was first delighted by the exchange before growing agitated and telling the guy to go back to his seat. However, “the cowboy” disregarded Cooper and persisted in questioning her. In the end, Labissoniere said, he managed to get “the cowboy” back into his seat.

Mucklow and Labissoniere had different accounts of the exchange. She said that a bored passenger had come up to her and wanted to read a sports magazine. She went to a spot right behind Cooper with the passenger, and they both searched for magazines there. After grabbing a copy of The New Yorker, the traveler went back to his seat.

Mucklow told him that there were no sky marshals on that trip when he replied, “If that is a sky marshal, I don’t want any more of that,” when she came back to sit with Cooper. “The cowboy” never gave his name and was never interrogated by the FBI, despite his brief encounter with Cooper.

Seattle First National Bank sent the $200,000 ransom in a package that weighed around nineteen pounds. Ten thousand unmarked $20 notes, the majority bearing serial numbers starting with “L” (signifying issued by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco), were photographed by the FBI and stored on microfilm. The two rear (primary) parachutes were acquired by Seattle police from a local stunt pilot, and the two front (reserve) parachutes were procured from a skydiving school in the area.

Release of Passengers

The parachutes were brought to the airfield, and Captain Scott told Cooper they would be landing shortly at 5:24 PST. Flight 305 touched down at Seattle-Tacoma Airport at 5:46 PM PST. Scott parked the plane distant from the main terminal on a runway that was just half illuminated, with Cooper’s approval.

Cooper insisted that the aircraft’s front door and the movable air stairs be the sole points of entry and escape and that only one airline agent approach the plane with parachutes and cash.

Al Lee, the operations manager for Northwest Orient in Seattle, was assigned as the courier. Lee dressed in civilian clothing for the mission, figuring that Cooper wouldn’t confuse his airline outfit for a law enforcement officer’s.

A member of the ground staff attached the moveable stairs while the passengers stayed seated. Mucklow followed Cooper’s instructions and took the ransom money out of the airplane via the front door. Upon her return, she walked Cooper in the final row, past the sitting passengers, carrying the money bag.

Then After, Cooper consented to the passengers’ release. Cooper examined the currency as they disembarked. Mucklow joked that she might have some of the money, hoping to defuse the situation.

Cooper nodded quickly and gave her a bundle of dollars, but she took back the cash right once and informed her that it was company policy not to take gratuities. She added that earlier in the trip, Cooper had attempted to tip her and the other two flight attendants with cash from his pocket, but they had all denied, citing the airline rules.

Cooper and the six staff members were the only ones still on board after the passengers had safely disembarked. Mucklow went outside the aircraft three times to fetch the parachutes, which she handed to Cooper at the back of the aircraft, as per Cooper’s orders.

Schaffner asked Cooper if she could get her pocketbook out of the compartment beneath his seat while Mucklow loaded the parachutes.

With the agreement, Cooper assured her, “I won’t bite you.” Cooper said, “Whatever you girls would like,” to flight attendant Hancock’s question about whether the flight attendants may depart.

Hancock and Schaffner then disembarked. Cooper claimed he didn’t need the printed instructions for utilizing the parachutes that Mucklow had taken with her when she delivered the last parachute.

Due to a delay in the refueling procedure, a second and subsequently a third truck were brought to the aircraft to finish the refueling. Cooper had protested that the money was given in a cloth bag rather than a rucksack, as he had instructed, and Mucklow added that during the wait, Cooper had to come up with a new plan for how to carry the money. Cooper took a pocketknife and cut the canopy off of one of the reserve parachutes. He then slipped some cash inside the parachute bag that was left empty.

Cooper turned down an FAA official’s request for a face-to-face meeting while they were on the plane. “This shouldn’t take so long,” and “Let’s get this show on the road,” Cooper growled in frustration. He then presented his flight plan and instructions to the cockpit crew, directing them to head southeast toward Mexico City at the lowest airspeed—roughly 100 knots, or 185 km/h, or 115 mph—and the highest altitude they could go, which was 10,000 feet (3,000 meters). Cooper further stipulated that the cabin must be pressurized, the landing gear must stay in place, and the wing flaps must be lowered by 15 degrees.

Cooper was advised by First Officer Rataczak that a second refueling would be required prior to approaching Mexico since the aircraft’s range was limited to around 1,000 miles (1,600 km) by this arrangement. After debating their choices, Cooper and the crew decided to refuel at Reno-Tahoe International Airport.

Cooper also instructed the aircraft to take off with its airstair extended and the rear evacuation door open. The home office of Northwest complained, saying that this was hazardous. In response, Cooper remarked, “It can be done, do it,” but he did not press the point, stating instead that he would lower the stairs once they were in the air. He insisted that Mucklow stays on board to support the mission.

Returning to the skies

Only Cooper, Mucklow, Captain Scott, First Officer Rataczak, and Flight Engineer Anderson were on Flight 305 when it took off at 7:40 p.m. The 727 was followed by two Lockheed T-33 trainers, diverted from an unrelated Air National Guard assignment, and two F-106 fighters from McChord Air Force Base.

To avoid Cooper’s view and to keep behind the slow-moving 727, the three planes flew in “S” formations. Cooper instructed Mucklow to descend the aft stairs upon takeoff. She expressed her concern about being sucked out of the airplane by him and the flight crew. She was advised by the flight crew to go to the cockpit and get an emergency rope so she could fasten herself to a seat.

Cooper said he didn’t want her going up front or the flight crew returning to the cabin, so he turned down the proposal. She requested him to cut some string from one of the parachutes so she could have a safety line as she kept talking to him about how afraid she was. He told her to go to the cockpit, close the curtain between the First Class and Coach sections, and not to come back, adding that he would lower the steps himself.

Mucklow pleaded with Cooper to “please, please take the bomb with you” before she departed. Cooper said that he would either remove the weapon or carry it with him. Turning to close the curtain barrier as she headed to the cockpit, she noticed Cooper standing in the aisle, wrapping what looked like the money bag around his waist.

It was four or five minutes after takeoff when Mucklow came into the cockpit. Mucklow was the last person to see the hijacker and stayed in the cockpit for the remainder of the journey to Reno. A warning light in the cockpit flashed at about 8:00 p.m., signaling that the aft staircase had been deployed.

Unsure of Cooper’s whereabouts, the flight crew stayed in the cockpit with the rear cabin door open and the stairs in place. Mucklow alerted Cooper over the cabin intercom that they were getting close to Reno and that he needed to raise the steps to allow for a safe landing.

As the pilots made their final approach to land, she reiterated her appeals, but the hijacker did not respond to Mucklow or the aircraft crew. At 11:02 p.m., Flight 305 touched down at Reno–Tahoe International Airport, still using the aft staircase.

Authorities from the FBI, state troopers, sheriff’s deputies, and Reno police formed a cordon around the aircraft, but they refrained from approaching it out of concern that the hijacker and the explosives were still inside.

Following a half-hour check by Captain Scott, who verified that Cooper was no longer inside the cabin, an FBI bomb squad deemed the cabin secure.

Examine

FBI officers found Cooper’s black clip-on tie, tie clip, and two of the four parachutes—one of which had been opened and had three shroud lines cut from the canopy—along with 66 latent fingerprints on the aircraft. FBI officers created a series of composite sketches after speaking with witnesses in Portland, Seattle, and Reno.

Agents from the FBI and local police started interrogating potential suspects right away. In response to the potential that the hijacker may have used his true name—or the same alias—in a prior crime, Portland police tracked down and spoke with D. B. Cooper, a Portland resident.

Despite having a minimal police history, the Portland Cooper was swiftly ruled out as a suspect. Reporter James Long misidentified the man as the hijacker in his haste to make a deadline. Reporter Clyde Jabin of United Press International reproduced Long’s blunder, and when other media outlets replicated it, the hijacker’s alias took on the name “D. B. Cooper.”

It was challenging to define the search area exactly because there were so many variables and characteristics. The ambient circumstances throughout the flight route fluctuated according to the aircraft’s location and altitude, the jet’s estimated velocity varied, and Cooper was the only one who knew how long he stayed in free fall before pulling his ripcord.

The Air Force F-106 pilots did not witness anyone falling from the aircraft, and they did not notice a parachute being released on their radar. Furthermore, it would be challenging to spot someone leaping into the pitch-black darkness while wearing all black, especially considering the poor visibility, cloud cover, and absence of ground illumination. There was no visual contact between the T-33 pilots and the 727.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover authorized, on December 6, 1971, the use of an Air Force SR-71 Blackbird to photograph and reconstruct the flight path of Flight 305 and try to find the objects Cooper had with him during the jump. The SR-71 attempted five flights to recreate the path of Flight 305, but the picture efforts were not successful because of low visibility.

By pushing a 200-pound (91 kg) sled out of the open airstair, FBI agents were able to replicate the upward motion of the tail section and the brief change in cabin pressure that the flight crew had reported at 8:13 pm in an experimental recreation that was conducted in the same aircraft used in the hijacking and in the same flight configuration.

According to early extrapolations, Cooper’s landing zone was located close to Lake Merwin, an artificial lake created by a dam on the Lewis River, on the southernmost expansion of Mount St. Helens, a few miles southeast of Ariel, Washington.

The areas in southwest Washington immediately south and north of the Lewis River were the focus of search operations, which were centered on the counties of Clark and Cowlitz.

Large swathes of the mostly wooded landscape were scoured by FBI agents and sheriff’s officers both on foot and by air. Farmhouses in the area were also searched door to door. Other search teams patrolled the waters of Yale Lake, the reservoir just east of Lake Merwin, with patrol boats. Cooper was nowhere to be seen, nor was any of the gear he probably packed.

The FBI organized an aerial search along the full flight path (referred to as “Vector 23” in most Cooper material and as Victor 23 in U.S. aviation nomenclature) from Seattle to Reno using fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters from the Oregon Army National Guard. Nothing pertinent to the hijacking was discovered despite the fact that many broken trees, several plastic pieces, and other items resembling parachute canopies were spotted and examined.

Soon after the spring thaw in early 1972, teams of FBI agents conducted another extensive ground search of Clark and Cowlitz Counties for eighteen days in March and eighteen days in April, with assistance from about two hundred soldiers from Fort Lewis, as well as US Air Force personnel, National Guard members, and civilian volunteers.

A submersible was utilized by the maritime salvage company Electronic Explorations Company to search the 200 feet (61 m) deep Lake Merwin. A skeleton was found by two local ladies in an abandoned Clark County building; it was subsequently determined to be the bones of a teenage girl named Barbara Ann Derry, who had been kidnapped and killed a few weeks prior.

In the end, the protracted search and recovery effort turned up no noteworthy tangible proof of the hijacking.

Cooper’s drop zone was first projected to be between the town of Battle Ground, Washington, to the south and the Ariel Dam to the north, based on preliminary computer predictions created for the FBI. Following a cooperative investigation with Northwest Orient Airlines and the Air Force, the FBI concluded in March 1972 that Cooper most likely leaped over the hamlet of La Center, Washington.

A report on the grocery store burglary in Heisson, Washington, which occurred around three hours after Cooper’s leap, was made public by the FBI in 2019. Northwest Airlines provided the FBI with a calculated drop zone that included the rural town of Heisson. The FBI reported that the thief grabbed just necessities, such as gloves and beef jerky. Cooper was said to be wearing slip-on shoes, however, the report mentions that the burglar was dressed in “military-type boots with a corregated [sic] sole”.

Look for money to pay the ransom.

The FBI gave lists of the ransom serial numbers to law enforcement organizations worldwide as well as banking institutions, casinos, racetracks, and other establishments that often carried out sizable cash transactions, a month after the hijacking.

A reward of 15% of the money recovered was given by Northwest Orient, up to a maximum of $25,000. U.S. Attorney General John N. Mitchell made the serial numbers public early in 1972. In return for an interview with a guy they falsely claimed was the hijacker, two men stole $30,000 from Newsweek writer Karl Fleming using counterfeit $20 notes printed with Cooper serial numbers.

The Oregon Journal publicized the serial numbers and offered $1,000 to the first individual to send in a ransom bill to the newspaper or any FBI field office in early 1973, while the ransom money was still missing. The Post-Intelligencer in Seattle extended a $5,000 incentive for a comparable offer.

The offers were valid until Thanksgiving of 1974, and despite reports of many close matches, no real banknotes were discovered. In compliance with a Minnesota Supreme Court decision, Global Indemnity Co., Northwest Orient’s insurer, paid the airline $180,000 (or $1,019,221 in 2023) for the ransom money in 1975.

Later developments

Subsequent investigation revealed that the first estimate of the landing zone was erroneous; Captain Scott, forced to pilot the aircraft manually due to Cooper’s requests for speed and altitude, eventually discovered his flight route was farther east than initially believed.

Further information from many sources, including Continental Airlines pilot Tom Bohan, who was four minutes behind Flight 305, revealed that the wind direction included in drop-zone estimates was incorrect, perhaps by up to 80°. This information, together with further data, indicated that the real drop zone was located in the Washougal River drainage area, south-southeast of the first estimate.

Ralph Himmelsbach, an FBI agent, remarked in 1986, “I have to confess if I were going to look for Cooper… I would head for the Washougal.” Throughout the years that followed, the Washougal Valley and its environs were explored extensively; however, no findings that may be linked to the hijacking have been found as of yet. Some experts have conjectured that whatever physical traces that may have remained may have been destroyed by Mount St. Helens’ 1980 explosion.

Investigation halted

The FBI stated on July 8, 2016, that the Cooper case’s ongoing investigation has been put on hold. The agency attributed this decision to the necessity to focus investigative resources and personnel on matters of higher and more immediate significance. Any valid physical evidence that comes to light later on, especially pertaining to the parachutes or the ransom money, would still be accepted by local field offices.

The 45-year inquiry resulted in a 66-volume case file that was saved for historical reasons at FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C., as well as on the FBI website. The public has access to all of the evidence. It is still the sole unresolved instance of air piracy in the annals of commercial aviation.

Tangible Proof

Four significant items of evidence were discovered by FBI investigators during their forensic examination of the aircraft, all of which had a clear physical connection to Cooper: a mother-of-pearl tie clip, a black clip-on tie, a hair from Cooper’s headrest, and eight Raleigh cigarette butts with filters from the armrest ashtray.

Necktie with a clip

Where Cooper had been sitting, in seat 18-E, FBI officers discovered a black clip-on necktie. A gold tie clip featuring a round mother-of-pearl setting in the middle was fastened to the tie. The FBI discovered that the tie had been withdrawn in 1968 after being solely offered at JCPenney department shops.

A partial DNA profile of Cooper was created by the FBI in late 2007 using traces discovered on his tie back in 2001. The FBI did admit, though, that there was no proof connecting Cooper to the location of the DNA sample.

“It’s difficult to draw firm conclusions from these samples,” stated FBI Special Agent Fred Gutt, “the tie had two small samples and one large sample.” In addition, the FBI posted a plea for information on Cooper’s identification and made available a file including never-before-released data, such as fact sheets, composite drawings, and Cooper’s airline ticket.

Reopening certain aspects of the case in March 2009, a group of “citizen sleuths” used GPS, satellite imaging, and other technology not accessible in 1971. The team, called the Cooper Research Team (CRT), consisted of metallurgist Alan Stone, scientific artist Carol Abraczinskas, and paleontologist Tom Kaye from the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle.

Though the CRT discovered, examined, and identified hundreds of biological and metallic particles on Cooper’s tie, they learned very little new about the buried ransom money or Cooper’s landing zone.

The CRT discovered Lycopodium spores by electron microscopy; these spores most likely originated from pharmaceutical sources. Along with particles of bismuth, antimony, cerium, strontium sulfide, aluminum, and titanium-antimony alloys, the scientists also discovered minute pieces of unalloyed titanium on the tie.

Cooper may have worked for Boeing or another aeronautical engineering organization, at a chemical manufacturing factory, or at a metal fabrication and production facility, according to the metal and rare-earth particles.

As Kaye put it, the unalloyed titanium was the substance of most consequence. In the 1970s, pure titanium was a scarce commodity, found exclusively in facilities that manufactured airplanes or in chemical industries that combined titanium with aluminum to hold very corrosive materials.

Cerium and strontium sulfide were employed by Portland firms that made cathode ray tubes, such as Tektronix and Teledyne, as well as by Boeing’s supersonic transport research project. Eric Ulis, a researcher at Cooper, has conjectured that Rem-Cru Titanium Inc., a metals producer and Boeing contractor, is connected to the titanium-antimony alloys.

Examples of Hair

Two hair samples were discovered in Cooper’s seat by FBI agents: one brown Caucasian head hair on the headrest and one strand of limb hair on the seat. The FBI Crime Laboratory concluded that the sample lacked sufficient distinct microscopic features to be valuable, thus the limb hair was destroyed.

Nonetheless, the FBI Crime Laboratory retained the head hair on a microscope slide after determining it was appropriate for comparison in the future. The FBI found that the hair sample had been misplaced in 2002 when trying to create Cooper’s DNA profile.

Cigarette butts

Agents from the FBI discovered eight Raleigh filter-tipped cigarette butts in the armrest ashtray of seat 18-E. The FBI Crime Laboratory was tasked with looking for fingerprints on them, but the investigators returned the butts to the Las Vegas field office after failing to locate any. When the FBI attempted to get DNA from the cigarette butts in 1998, they found that the butts had been incinerated while in the Las Vegas field office’s care.

Money from the Ransom was Recovered

Eight-year-old Brian Ingram was on vacation with his family on the Columbia River on February 10, 1980, at a seashore known as Tina (or Tena) Bar. Tina was located 20 miles (32 km) southwest of Ariel and approximately 9 miles (14 km) downstream from Vancouver, Washington.

He found three envelopes containing around $5,800 in ransom money while he was cleaning up the sandy riverbank in preparation for a bonfire. Despite their long exposure to the weather, the banknotes had crumbled and were still wrapped in rubber bands.

Two packages containing one hundred twenty-dollar notes apiece and a third packet containing ninety bills, all in the same sequence as when they were delivered to Cooper, were verified by FBI specialists as being part of the ransom.

In the end, the finding led to additional speculation and unanswered questions. According to the initial claims made by scientists and investigators, the bundles of banknotes freely flowed into the Columbia River from one of its several tributaries.

An Army Corps of Engineers hydrologist observed that the bills were “matted together” and had broken down in a “rounded” way, suggesting that they “had been deposited by river action” rather than being purposefully buried.

The results confirmed the notion that Cooper had landed neither in or near Lake Merwin, the Lewis River, or any of its tributaries supplying the Columbia River downstream from Tina Bar, but rather close to the Washougal River, which empties into the Columbia upstream from the discovery location.

The “free-floating” theory was unable to account for the ten missing notes from a single packet or the way the three packets held together after being separated from the other cash. Geological evidence and physical evidence were irreconcilable, according to Himmelsbach, who stated that rubber bands would have long ago degraded if free-floating bundles had washed up on the shore “within a couple of years” of the hijacking. According to geological data, the bills reached Tina Bar after 1974, when the Corps of Engineers conducted dredging on that section of the river.

The bills came long after the dredging was finished, according to geologist Leonard Palmer of Portland State University, who discovered two separate layers of sand and debris between the clay the dredge had deposited on the riverbank and the sand layer in which the dollars were buried.

Diatom research on the banknotes conducted in late 2020 indicates that the bundles discovered at Tina Bar were neither buried dry or immersed in the river during the November 1971 incident. Since only spring-blooming diatoms were discovered, the money had to have reached the water many months after the hijacking.

Following lengthy discussions, the recovered bills were split evenly between Northwest Orient’s insurer, Royal Globe Insurance, and Brian Ingram in 1986; the FBI kept 14 of the bills as evidence. In 2008, fifteen of Ingram’s bills were sold at auction for around $37,000, which translates to $52,000 in 2023.

The sole verified tangible proof of the hijacking discovered outside the airplane is still the ransom money from the Columbia River.

Parachutes

Cooper requested and was given two primary and two reserve parachutes during the hijacking. Local skydiving school provided the two backup (front) parachutes, while pilot Norman Hayden provided the two primary (back) parachutes. The two primary parachutes were defined as emergency bailout parachutes by Earl Cossey, the parachute rigger who packed all four parachutes sent to Cooper (as opposed to sports parachutes that skydivers would employ).

Cossey went on to say that the primary parachutes could not be guided and were designed to deploy instantly upon the pulling of a ripcord, similar to military parachutes. FBI officers found that Cooper had left two parachutes behind, one reserve (front) and one main (back) parachute when the jet landed in Reno.

The primary parachute that was left behind was still in place, but the reserve parachute had been opened and three shroud lines had been removed. FBI agents identified the unutilized main parachute as a Model NB6 (Navy Backpack 6), which is currently on exhibit at the Washington State Historical Society Museum.

Cooper was given two reserve (front) parachutes, one of which was an ineffective training parachute meant to be used solely for demonstrations in the classroom. Cossey claims that the interior canopy of the reserve parachute was stitched together so that skydiving trainees may experience the sensation of pulling a ripcord on a packed parachute without the canopy actually opening.

FBI officers conjectured that Cooper was not a skilled parachutist as someone with expertise would have known that this reserve parachute was a “dummy parachute” when it was discovered outside the plane upon landing in Reno. Days after the hijacking, it was discovered that Cooper was not provided any parachute harnesses with the D-rings needed to attach backup parachutes.

It is unknown what Cooper did with this “dummy” parachute as it was not discovered in the aircraft, despite the fact that he was unable to fasten it to his primary harness as a backup parachute. Cooper took off the stitched cover, Cossey surmised and used the empty reserve container as a satchel for spare cash. According to Tina Mucklow’s evidence, which supported Cossey’s conjecture, Cooper had tried to stuff money inside a parachute container.

A deer hunter discovered the instruction sign for lowering the aft airstair of a 727 in November 1978. Situated along Flight 305’s basic flight route, the placard was discovered next to a logging road around 13 miles (21 km) east of Castle Rock, Washington, and north of Lake Merwin.

Theories, Conjectures, and Speculations

The FBI conducted an active investigation for 45 years, during which time it released some of its preliminary findings and working theories based on witness testimony and a few physical evidence.

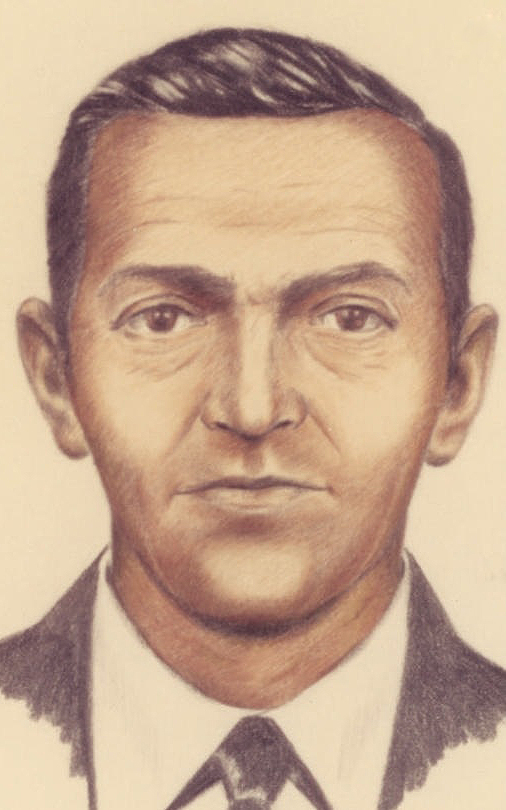

Illustrations

The FBI created drawings of Cooper throughout the first year of the inquiry by using the passengers’ and flight crew’s eyewitness testimonies. Released on November 28, 1971, the first sketch, officially named Composite A, was finished a few days after the hijacking.

Witnesses said that the Composite A sketch—disregardingly dubbed “Bing Crosby”—was not a true representation of Cooper. Witnesses said that the Composite A drawing depicted a narrow-faced young guy who did not resemble Cooper or convey his casual, “let’s get this over with” attitude. Florence Schaffner, a flight attendant, informed the FBI on many occasions that the Composite A drawing was a very bad likeness of Cooper.

FBI artists created a second composite sketch after several eyewitnesses said that Composite A was not an accurate portrayal. The second Composite B drawing, finished in late 1972, was meant to capture Cooper’s age, skin tone, and facial shape more precisely.

The drawing, according to the eyewitnesses who saw Composite B, was more realistic; yet, the Composite B Cooper appeared excessively “angry” or “nasty”. A flight attendant recalled Cooper as having a “more refined appearance” and thought the Composite B drawing was a “hoodlum”. In addition, witnesses said that the Composite B drawing showed a guy who was paler in appearance and older than Cooper.

The FBI artists improved and modified the Composite B sketch based on the critiques provided. The FBI completed their third drawing of Cooper, updated Composite B, on January 2, 1973. A flight attendant described the updated Composite B as bearing “a very close resemblance” to the hijacker. Another flight attendant expressed her opinion that “the hijacker would be easily recognized from this sketch.”

The FBI determined in April 1973 that the updated Composite B sketch was the most accurate representation of Cooper they could create and ought to be regarded as the official drawing of Cooper.

Doubtful profiling

The two flight attendants who interacted with Cooper the most, Schaffner and Mucklow, were interviewed on the same night in two different cities. They provided almost exact descriptions, stating that they were in their mid-40s, about 5 feet 10 inches (1.78 meters) tall, with short black hair combed back, weighing between 170 and 180 pounds, with swarthy or olive skin tone, and no noticeable accent.

Schaffner was the only one who could remember the color of his eyes; he said they were brown. Bill Mitchell, a University of Oregon student who sat across from Cooper during the three hours between takeoff in Portland and arrival in Seattle, provided evidence that the FBI strongly relied upon. Mitchell repeatedly interviewed Cooper for what would eventually be known as Composite Sketch B.

He described Cooper as being somewhat smaller than the flight attendants, stating that he thought Cooper was between 5 feet 9 inches (1.75 m) and 5 feet 10 inches (1.78 m), and that at 6 feet 2 inches (1.88 m), he was “way bigger” than Cooper. His descriptions of Cooper were essentially the same as those of the flight attendants.

One of the few other passengers, Robert Gregory, gave the FBI a complete description of Cooper in addition to a brief description, stating that he was five feet nine inches (1.75 meters) tall. Gregory said he thought Cooper was either American Indian or Mexican-American.

Based on testimony that he recognized Tacoma from the air as the jet circled Puget Sound and his accurate comment to Mucklow that McChord Air Force Base was about 20 minutes drive from Seattle-Tacoma Airport—a detail that most civilians would not know or comment upon—it appeared that Cooper knew the area well and may have been an Air Force veteran.

It’s quite likely that his financial circumstances were dire. Ralph Himmelsbach, a retired FBI top investigator, said that extortionists and other criminals who take huge sums of money almost always do so because they have an immediate need for the money; if not, the crime is not worth the significant risk.

Alternatively, Cooper could have jumped “just to prove it could be done” as “a thrill seeker”.

An eight-page suspect profile was published by the FBI internally in May 1973. According to the profile, Cooper was not a sports skydiver but rather a parachutist with military training because, aside from his apparent ease using the military-style parachutes he was given, his age would have made him stand out among other sports skydivers, increasing the possibility that someone in the community would have noticed him right away.

The report also conjectured that Cooper was a frequent exerciser because of remarks made by many witnesses about his youthful-looking physique. The fact that the one drink they gave him soon spilled and he never asked for more gave them additional reason to believe he wasn’t an alcoholic or heavy drinker.

According to the profile, an alcoholic would probably have been unable to resist alcohol throughout the tense and protracted hijacking. The FBI calculated how many cigarettes he smoked throughout the hijacking and came to the conclusion that he smoked around one pack each day.

The FBI came to the conclusion that Cooper was smarter than the average criminal based on his demeanor, which included his extensive vocabulary and appropriate use of aviation jargon. Cooper was the kind of person who probably wouldn’t need or want an accomplice to commit a crime because of his ability to rapidly and skillfully adjust to different situations as they developed.

Agents surmised that Cooper adopted his alias from a well-known French-language Belgian comics series that starred the fictional character Dan Cooper, a test pilot for the Royal Canadian Air Force who underwent many valiant adventures, including skydiving.

An FBI website scan of the series’ cover shows test pilot Cooper skydiving. Since the Dan Cooper comics were never published in English or brought into the United States, rumors circulated that he had come across them while serving in Europe.

Understanding and preparation

The FBI surmised that Cooper had meticulously planned the hijacking and possessed in-depth, specialized knowledge of aviation, the surrounding topography, and the capabilities of the 727 based on the evidence and Cooper’s methods.

Cooper opted for the last row in the back cabin for three reasons: to keep an eye on everything going on in front of him and react accordingly; to reduce the likelihood that someone from behind might approach or assault him; and to blend in with the other passengers.

Cooper insisted on receiving four parachutes to make it seem unlikely that he would coerce one or more captives to jump with him and to make sure he wouldn’t be purposefully provided with compromised equipment.

Cooper’s decision to employ a bomb—rather than other weapons that hijackers had previously used—thwarted any multiple efforts to rush him, according to FBI agent Ralph Himmelsbach.

Cooper took cautious not to leave any trace. He insisted on receiving all notes, whether they were written by him or on his behalf, back from Mucklow before he leaped. Mucklow said that after lighting one of his cigarettes with the final match in his paper matchbook, he insisted that she give the matchbook back to him when she tried to discard it. He left his clip-on tie at his seat, but despite his painstaking efforts, he was unable to obtain any proof.

The main reason Cooper selected the 727 was its design, even though he was obviously aware of its capabilities and secret features. As one of the few passenger jets from which a parachute drop could be accomplished with ease, the 727 was distinguished by its aft airstair and the arrangement of its three engines. Moreover, Mucklow alerted the FBI that Cooper “seemed specifically well informed in refueling procedures” and that Cooper seemed to know how long the 727 usually took to refuel.

Cooper demonstrated a specialized understanding of aviation tactics and the capabilities of the 727 by recommending a 15° flap setting; in contrast to most commercial jet airliners, the 727 could maintain low-altitude, sluggish flying without stalling.

By requesting a certain flap setting, Cooper was also able to regulate the 727’s altitude and velocity without having to go into the cockpit, where he may have been overwhelmed by the three pilots. Speaking with Cooper over the intercom during the hijacking, First Officer Bill Rataczak informed the FBI that “[Cooper] displayed a specific knowledge of flying and aircraft in general.”

The most important piece of information Cooper shared concerned a feature that was both exclusive to the 727 and top secret: the ability to use the aft airstair while in flight and the inability to override the single activation switch at the back of the cabin from the cockpit.

Cooper had obviously intended to utilize the aft staircase for his escape and was familiar with how to use it. According to FBI rumors, Cooper was aware that the Central Intelligence Agency was dropping supplies and operatives into enemy areas during the Vietnam War utilizing 727 aircraft.

The civilian personnel were not notified that the aft airstair could be lowered midflight, nor that its operation could not be overridden from the cockpit, because no circumstance on a passenger flight would require such an action.

It’s unclear how much experience Cooper had with parachutes, but he seemed to know about them. Cooper “put on [his] parachute as though he did so every day,” according to Mucklow, who also told a journalist that Cooper “appeared to be completely familiar with the parachutes which had been furnished to him.” There have been rumors that Cooper was a military parachutist and not a civilian skydiver because of his acquaintance with the military-style parachutes he was given.

According to Larry Carr, who oversaw the investigation team from 2006 to 2009, Cooper was not a paratrooper. Rather, Carr surmises that Cooper had worked as a cargo loader on Air Force planes. He would get expertise and experience in aviation through a cargo-loading assignment: cargo loaders are trained to do basic jumps, wear emergency parachute gear, and are capable of removing objects from airplanes while in flight. Cooper would have some experience with parachutes from his work as a freight loader, “but not necessarily sufficient knowledge to survive the jump he made”.

Cooper’s destiny

FBI officers had doubts about Cooper’s survival of his leap from the start of their inquiry. Cooper’s apparent lack of skydiving experience, his lack of appropriate gear for his jump and survival, the temperature and unfavorable weather on the night of the hijacking, the wooded area into which Cooper jumped, his ignorance of his landing area, and the unutilized ransom money were just a few of the arguments and facts the FBI used to support their conclusion.

First of all, Cooper didn’t seem to have the knowledge, expertise, or experience needed for the kind of skydiving leap he was attempting. Carr continued: “We originally thought Cooper was an experienced jumper, perhaps even a paratrooper.” Carr went on: “After a few years, we came to the conclusion that this was just not true.

Wearing loafers and a trench coat, no seasoned parachutist would have jumped in the dark, rainy night with a wind gusting at 172 mph (77 m/s) straight into his face. It was just too dangerous.”

On the other hand, Cooper would not have had a great deal of expertise to survive the leap; according to skydiving instructor Earl Cossey, who provided the parachutes, “anyone who had six or seven practice jumps could accomplish this”. But Cossey also pointed out that leaping at night significantly raised the possibility of getting hurt, and Cooper most likely would have landed with serious ankle or leg damage had he not had jump boots.

Secondly, Cooper didn’t seem to have the gear needed for the leap or for wilderness survival. Cooper did not carry a helmet or ask for one, so in November, he leaped over Washington State at 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) into a 15 °F (−9 °C) wind without adequate gear to ward off the intense wind cold.

The contents of Cooper’s 4 in × 12 in × 14 in (10 cm × 30 cm × 36 cm) paper bag are unknown, but since Cooper did not use any of the contents to help him during the hijacking, the FBI surmised that the bag held goggles, boots, and gloves that Cooper would need for his jump.

Thirdly, Cooper did not appear to have a helper on the ground ready to assist him in getting away. Cooper did not provide the flight crew with a predefined flight route, thus such an arrangement would have needed both a precisely timed leap and their participation.

Furthermore, Cooper accepted the flight crew’s suggestion to change course and fly from Seattle to Reno for refueling, but he had no method of informing a companion of his revised itinerary. Cooper’s inability to locate himself, get a heading, or observe his landing zone was made more difficult by the dense cloud cover and lack of ground visibility.

Ultimately, the retrieved half was discovered to be unused, and the ransom money was never spent. Carr stated: “Diving into the wilderness without a plan, without the right equipment, in such terrible conditions, he probably never even got his chute open.”

According to FBI agent Richard Tosaw’s theory, Cooper drowned in the Columbia River after becoming too weak due to hypothermia during his leap. But FBI agents’ opinions about Cooper’s eventual destiny did not all agree. In a 1976 Seattle Times report, a top FBI official expressed anonymous opinions, saying, “I think [Cooper] made it.” That night, I believe he slept in his own bed. The night was clear. Since much of the nation is flat, he could have easily left.

Straight ahead on the road. Hell, at the time they weren’t even trying to find him there. They believed he had moved on. He might simply stroll down the street.”

No solid proof of Cooper’s demise has been discovered. Five individuals attempted to carry out similar hijackings in the months after Cooper’s, and all five managed to escape via parachute.

FBI lead case agent Ralph Himmelsbach was compelled to reconsider his beliefs and ideas about Cooper’s prospects of life after learning that some of the copycats—some of whom had conditions and circumstances identical to Cooper’s jump—survived.

Himmelsbach gave the following three hijackers as instances of successful jumpers: Martin McNally, Frederick Hahneman, and Richard LaPoint. Their circumstances were comparable to Cooper’s escape.

Hijacker Martin McNally jumped at night over Indiana with only a reserve chute and no safety equipment. McNally needed to be instructed how to put on his parachute, in contrast to Cooper, who seemed to know how to use one.

Furthermore, the pilot of McNally’s aircraft raised the speed to 320 knots, which was almost twice as fast as Flight 305 at the moment of Cooper’s leap. McNally leaped violently because to the increased wind speed, and the money bag tore from him right away, but he landed safely aside from a few minor bruises and scrapes.

Frederick Hahneman, 49, jumped into a Honduran jungle at night in order to hijack a 727 in Pennsylvania and survive. Richard LaPoint, a third impostor, took control of a 727 in Nevada. LaPoint landed in the snow after leaping into the frigid January wind over northern Colorado while wearing only pants, a shirt, and cowboy boots. Himmelsbach said in 2008 that he had reevaluated his estimate of Cooper’s chances of life after first estimating only a 50% probability.

By 1976, the majority of published legal studies agreed that there would not be much of an impact from the statute of limitations for the hijacker’s prosecution about to expire. As the meaning of the Act is subject to variation in individual cases and across courts, a prosecutor may contend that Cooper had lost legal immunity based on a number of legitimate technical grounds.

A Portland grand jury issued an indictment in absentia in November 1976 charging “John Doe, a.k.a. Dan Cooper” with violating the Hobbs Act and engaging in air piracy. In the unlikely event that the hijacker is captured down the road, the prosecution will be formally resumed thanks to the indictment.

Suspects

The FBI processed almost a thousand “serious suspects” between 1971 and 2016, including a variety of attention seekers and deathbed confessors.

Ted Braden

Theodore Burdette Braden Jr. (1928–2007) was a skilled skydiver, a convicted criminal, and a Special Forces commando in the Vietnam War. Many in the Special Forces world thought he was Cooper, both at the time of the hijacking and in the years that followed.

Originally from Ohio, Braden enlisted in the Army in 1944 when he was 16 years old and served with the 101st Airborne in the Second World War. In the end, he developed into one of the Army’s top parachutists; according to his military statistics, he has done 911 jumps. He frequently competes for the Army in international skydiving competitions.

Braden led a squad in the 1960s for the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACVSOG), a Green Beret-led covert commando force that conducted unconventional warfare missions in Vietnam. In addition, he instructed members of Project Delta in HALO jumping tactics while working as a military skydiving instructor.

Braden conducted clandestine missions in North and South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia throughout his 23-month stay in Vietnam. Braden left his unit in Vietnam in December 1966 and traveled to the Congo to work as a mercenary. He was only in the country for a short while when CIA operatives caught him and brought him back to the US for a court-martial.

In exchange for maintaining his secret regarding the MACVSOG program, Braden was granted an honorable discharge and barred from re-entering the military, even though he had committed a grave crime by deserting during a war.

Journalist and fellow Special Forces veteran Don Duncan wrote a profile of Braden in the October 1967 issue of Ramparts magazine, describing him as someone with a “secret death wish” who “continually places himself in unnecessary danger but always seems to get away with it,” referring specifically to Braden’s disdain for military skydiving safety regulations. Additionally, Duncan stated that Braden was “continuously involved in shady deals to make money” when he was serving in Vietnam.

Braden’s life story is largely unknown after his military discharge in 1967, but at the time of the hijacking, he was driving a truck for Consolidated Freightways, which had its headquarters in Vancouver, Washington, which is located not far from the suspected dropzone of Ariel, Washington, and just across the Columbia River from Portland.

It is also known that the FBI looked into him in the early 1970s for allegedly stealing $250,000 from a trucking scheme he had invented, although he was never prosecuted for this claimed offense. It’s unclear if Braden was found guilty in the 1980 Federal grand jury indictment for transporting an 18-wheeler loaded with stolen merchandise from Arizona to Massachusetts.

Braden was detained in Pennsylvania two years later for not having a driver’s license and for using a stolen car with fake license plates. Reference 268 In the end, Braden was detained in a federal prison in Pennsylvania during the late 1980s, but it is unclear what exact offense he had committed.

A family relative referred to him as “the perfect combination of high intelligence and criminality” despite the fact that he was a skilled soldier and not widely loved personally. He probably had the then-classified information of being able to leap from a 727 and the necessary requirements from his experience handling clandestine operations in Vietnam; he could even have done it himself on MACVSOG missions.

Although the two flight attendants claimed that Braden was at least five feet ten inches (178 cm) tall, his military records place him at five feet eight inches (173 cm), which is shorter than his actual height. However, it should be noted that Braden may have looked taller in shoes because this measurement was made while he was still wearing stockings.

He was 43 years old at the time of the hijacking, had short black hair, a medium athletic build, and a dark complexion from years of outdoor military service—all characteristics that fit Cooper’s description.

Christiansen, Kenneth Peter

After viewing a television program on the Cooper hijacking in 2003, Lyle Christiansen, a native of Minnesota, was persuaded that Cooper was actually his late brother Kenneth (1926–1994). Following several ineffective attempts to persuade the FBI and writer and filmmaker Nora Ephron—who he anticipated would film a movie based on the case—he got in touch with New York City-based private investigator Skipp Porteous.

In a book published in 2010, Porteous made the assumption that Christiansen was the hijacker. The circumstantial evidence connecting Christiansen to the Cooper case was also summed up in an episode of Brad Meltzer’s Decoded, a History series, that aired the following year.

Christiansen trained as a paratrooper after enlisting in the Army in 1944. When he was sent in 1945, World War II had already concluded, but in the late 1940s, while stationed in Japan with occupation troops, he occasionally did training jumps.

1954 saw him leave the Army and work as a worker for Northwest Orient, assigned to the airline’s Far East stopover at Shemya Island in the Aleutians. After that, he worked as a flight attendant in Seattle before moving on to become a purser. Christiansen was 45 years old at the time of the hijacking, but compared to Cooper’s reports by eyewitnesses, he was leaner (150 pounds, or 68 kg) and shorter (5 ft 8 in, or 173 cm).

Christiansen, like the hijacker, was a smoker and showed a taste for bourbon, Cooper’s preferred beverage. Although she was unable to positively identify the hijacker, stewardess Florence Schaffner told author Geoffrey Gray that pictures of Christiansen more closely matched her recall of the hijacker’s looks than those of other suspicions.

Even with the media attention brought about by Porteous’s book and the 2011 TV program, the FBI continues to insist that Christiansen is not a key suspect. It points to the lack of any direct damning evidence and the weak fit to the physical descriptions provided by eyewitnesses.

Jack Coffelt

Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith, the last living descendent of Abraham Lincoln, was said to have had a driver and confidant in Bryant “Jack” Coffelt (1917–1975), a con artist, former prisoner, and alleged government informant.

In 1972, he started pretending to be Cooper and made an attempt to sell his narrative to a Hollywood production firm through a middleman, James Brown, a former cellmate. He claimed to have hurt himself and lost the ransom money when he landed close to Mount Hood, which is located around 50 miles (80 km) southeast of Ariel. Although Coffelt was in his mid-fifties in 1971, photos of him resemble the composite drawings.

On the day of the hijacking, he was allegedly in Portland, and at that time, he apparently had leg injuries consistent with a skydiving accident.

After reviewing Coffelt’s story, the FBI determined that it was a fabrication since it differed from material that had not been made public in a number of respects. Brown kept selling the narrative even after Coffelt passed away in 1975. Several media outlets, such as CBS News’ 60 Minutes, had a look at it but decided against it.

Lynn Doyle Cooper

In July 2011, Lynn Doyle “L. D.” Cooper (1931-1999), a leather craftsman and veteran of the Korean War, had his niece Marla Cooper suggest him as a suspect. She remembered as an eight-year-old organizing a “very mischievous” activity at her grandmother’s home in Sisters, Oregon, which is 150 miles (240 km) southeast of Portland, with another uncle and Cooper.

They also planned to use “expensive walkie-talkies” in this activity. The uncles claimed to be hunting turkeys the following day, but L. D. Cooper returned home with a bloodied shirt, claiming it was from an automobile accident. That same day, Flight 305 was hijacked. Marla later said that her parents started to suspect L. D. of being the hijacker.

She also remembered that her uncle, who passed away in 1999, “had one of his comic books thumbtacked to his wall” and was a Canadian comic book hero named Dan Cooper, despite the fact that he was neither a skydiver nor a paratrooper.

An alternate witness drawing was released by New York magazine in August 2011. It was purportedly based on a description provided by Flight 305 eyewitness Robert Gregory and showed horn-rimmed sunglasses, a wide-lapeled suit jacket with a “russet” tint, and marcelled hair.

According to the article, L. D. Cooper (as well as Duane Weber, see below) had wavy hair that gave off a marcelled appearance. The FBI declared that an L. D. Cooper guitar strap had not yielded any fingerprints. After a week, they stated that his DNA did not fit the partial profile of DNA taken from the hijacker’s tie, but they did not say for sure that the organic material from the tie came from the hijacker.

Barbara Dayton

Originally called Robert Dayton, Barbara Dayton (1926–2002) was a recreational pilot and librarian at the University of Washington. She served in the American Merchant Marines and the Army during World War II. Dayton worked with explosives for construction companies after being released from the military and wanted to work for a commercial airline, but he was unable to get a commercial pilot’s license.

In 1969, Dayton underwent gender reassignment surgery, changing her name to Barbara. It is said that Dayton was the first patient in Washington State to undergo this procedure. Two years later, she claimed to have faked the hijacking and presented herself as a guy in an attempt to “get back” at the airline business and the FAA for its unforgiving regulations and procedures that had kept her from pursuing her dream of becoming an airline pilot.

The ransom money, according to Dayton, was stashed away in a cistern close to Woodburn, Oregon, a community located south of Portland. Eventually, perhaps upon discovering that charges for hijacking may still be filed, she renounced the whole account. She also did not really fit the physical description.

William Gossett

Veteran of the Army, Marine Corps, and Army Air Forces, William Pratt Gossett (1930–2003) served in both Korea and Vietnam. He trained in leaping and outdoor survival during his time in the military. It was well known that Gossett was fixated with the Cooper hijacking. Galen Cook, an attorney who has gathered Gossett-related material for years, claims that Gossett once gave his sons the key to a safe deposit box in Vancouver, British Columbia, and claimed it had the long-lost ransom money.

Gossett is not directly implicated by the FBI, and they are unable to locate him in the Pacific Northwest at the time of the hijacking. “There is not one link to the D. B. Cooper case,” stated Special Agent Carr, “other than the statements [Gossett] made to someone.”

Joe Lakich

Joe Lakich (1921–2017), a former Major in the U.S. Army and veteran of the Korean War, lost his daughter Susan Giffe less than two months before to the hijacking due to an FBI-conducted hostage negotiation gone awry. For decades, hostage negotiators would use the sequence of events that resulted in Lakich’s daughter’s death as a model of what not to do in a hostage scenario.

Afterward, he and his spouse filed a lawsuit against the FBI, and in the end, an Appeals Court found in their favor, concluding that the FBI had behaved carelessly throughout the hostage negotiations.

It was later discovered that tiny fragments of rare metals, including unalloyed titanium, were present in Cooper’s tie, which led Lakich to become a prime suspect in the investigation. Few persons in that era are thought to have had contact with such materials, and Cooper may have been an engineer or manager in an electronics manufacturing setting.

Lakich was employed as a production supervisor at an electronics capacitor plant in Nashville at the time of the hijacking, and it is probable that he came into contact with the materials discovered on the tie. In response to Tina Mucklow’s question about why he was carrying out the hijacking, Cooper said, “It’s not because I have a grudge against your airlines, it’s just because I have a grudge.”

Some people think that Lakich harbored this “grudge” since the FBI had failed to save his daughter less than two months prior.

John List

Fifteen days before to the Cooper hijacking, John Emil List (1925–2008), an accountant and war veteran, killed his mother, three teenage children, and wife in Westfield, New Jersey. He then took $200,000 from his mother’s bank account and vanished.

The timing of his departure, the fact that he fit the hijacker’s description more than once, and the notion that “a fugitive accused of mass murder has nothing to lose” all attracted the attention of the Cooper task team.

List denied having anything to do with the Cooper hijacking after he was apprehended in 1989; the FBI no longer views him as a suspect since there is insufficient evidence to support his claims. In 2008, List passed away while incarcerated.

Ted Mayfield

Theodore Ernest Mayfield, who passed away in 2015, was a competitive skydiver, pilot, Special Forces veteran, and skydiving teacher. After two of his pupils died when their parachutes failed to open, he was convicted in 1994 of negligent homicide and was subsequently found to have been indirectly responsible for thirteen more skydiving deaths as a result of defective gear and inadequate instruction.

He was given a three-year probationary period in 2010 for operating an aircraft 26 years after he had lost his rigger and pilot’s licenses. FBI Agent Ralph Himmelsbach, who knew Mayfield from a previous altercation at a nearby airport, stated that he was brought up many times as a suspect early in the inquiry.

He was excluded in part because less than two hours after Flight 305 touched down in Reno, he called Himmelsbach to offer guidance on accepted skydiving procedures, potential landing zones, and contact details for nearby skydivers.

Richard McCoy Jr.

Richard McCoy (1942–1974) was an Army veteran who flew helicopters with the Green Berets during his second tour of service in Vietnam, having earlier served as an expert in demolitions. After serving in the armed forces, he joined the Utah National Guard as a warrant officer and took up skydiving recreationally. He eventually wanted to work as a Utah State Trooper.

McCoy executed the most well-known of the imitative hijackings on April 7, 1972. In Denver, Colorado, he boarded United Airlines’ Boeing 727, Flight 855, which had aft stairs. He then demanded $500,000. and four parachutes, waving what turned out to be a paperweight that looked like a hand grenade and an empty revolver.

Upon receiving the money and parachutes at San Francisco International Airport, McCoy gave the order to restart the aircraft and dropped out over Provo, Utah, leaving his fingerprints on a magazine he was reading and his scrawled instructions for hijacking behind.

He was apprehended on April 9 while in possession of the ransom money, and following his trial and conviction, he was given a 45-year term. Two years later, he and a few accomplices crashed a garbage truck through the main gate of Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary to escape. Three months after being located in Virginia Beach, McCoy was shot and murdered by FBI officers.

Parole officer Bernie Rhodes and retired FBI agent Russell Calame claimed to have recognized McCoy as Cooper in their 1991 book D.B. Cooper: The Real McCoy. They pointed to the striking parallels between the two hijackings, McCoy’s family’s insistence that he was Cooper, and the tie and mother-of-pearl tie clip he left aboard the aircraft. The FBI agent who killed McCoy was among many who supported their claim. “When I shot Richard McCoy,” he stated, “I shot D. B. Cooper at the same time.”

The FBI does not view McCoy as a suspect in the Cooper case, despite the fact that there is no reasonable doubt that he committed the Denver hijacking. This is due to discrepancies in his age and description (for example, he was 29 years old and had projecting ears), his skydiving skill, which was significantly higher than that of the hijacker, and reliable evidence indicating that McCoy was in Las Vegas the day of the Portland hijacking and at home in Utah the following day, enjoying Thanksgiving dinner with his family.

Vincent C. Petersen

Independent researcher Eric Ulis declared Vincent C. Petersen to be a person of interest at a news conference on November 11, 2022. Ulis found three particles in the spectrum analysis of Cooper’s tie that seemed to be an extremely unusual titanium antimony alloy. Petersen was employed by Rem-Cru, a Midland, Pennsylvania-based firm that subsequently relocated to the Pittsburgh metropolitan area, producing titanium-antimony alloys.

Sheridan Peterson

After serving in the Marine Corps during World War II, Sheridan Peterson (1926–2021) worked as a technical editor for Seattle-based Boeing. Soon after the skyjacking, Peterson’s background as a smokejumper and enjoyment of physical danger, together with his comparable look and age (44) to Cooper’s description, piqued investigators’ curiosity as a potential suspect.

Peterson frequently made fun of the media by questioning if he was actually Cooper. After years of investigation, businessman Eric Ulis declared he was “98% convinced” that Peterson was Cooper; nevertheless, when questioned by FBI investigators, Peterson claimed he was in Nepal during the hijacking. In 2021, he passed away.

When compared to a DNA sample from one of Peterson’s live daughters, the study of DNA found on Cooper’s tie for History’s Greatest Mysteries on the History Channel revealed that Peterson was not a match for Cooper. Since then, Eric Ulis has recanted his claim that Peterson could have been Cooper.

Robert Rackstraw

During the Vietnam War, Robert Wesley Rackstraw (1943–2019), a retired pilot and former prisoner, fought with the Army helicopter crew and other troops. In February 1978, he was brought to the notice of the Cooper task force following his arrest in Iran and deportation to the United States on allegations of possessing explosives and check kiting.

A few months later, after being freed on bond, Rackstraw tried to send in a fictitious mayday call to controllers, claiming to be jumping out of a rented aircraft over Monterey Bay. He was later taken into custody by police in Fullerton, California, on suspicion of fabricating federal pilot certifications. The aircraft he had claimed to have abandoned was discovered in a neighboring hangar, having been painted over.

Despite his youth (he was just 28 in 1971), his criminal record, and his physical similarity to Cooper composite sketches, Cooper investigators discarded him as a suspect in 1979 when no concrete proof of his involvement could be produced.

Rackstraw was mentioned as a suspect in a book and on a History channel broadcast in 2016. Author of the book Thomas J. Colbert and lawyer Mark Zaid filed a lawsuit on September 8, 2016, requesting that the FBI reveal the Cooper case file under the Freedom of Information Act.

At an unidentified area in the Pacific Northwest, Colbert and a team of volunteer investigators discovered what they thought to be “a decades-old parachute strap” in 2017. Later in 2017, they found a piece of foam that they thought could have come from Cooper’s parachute bag.

The confession letter, which was first written in December 1971 and had codes matching three units Rackstraw was a part of while in the Army, was revealed to Tom and Dawna Colbert in January 2018.

According to reports, one of the flight attendants on Flight 305 “did not find any similarities” between Cooper’s looks and pictures of Rackstraw from the 1970s. The fresh accusations were described as “the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard” by Rackstraw’s lawyer, and Rackstraw said to People magazine, “It’s a lot of [expletive], and they know it is”.

The FBI declined to provide more commentary. In a 2017 phone conversation, Rackstraw said that the 2016 investigations were the reason he was fired. “I told everybody I was [the hijacker],” Rackstraw said to Colbert before revealing that the confession was a farce. 2019 saw his passing.

Walter R. Reca

Walter R. Reca was an intelligence operative and former military paratrooper who lived from 1933 until 2014. In 2018, his buddy Carl Laurin put him up as a potential suspect. Reca admitted to Laurin that he was the hijacker in a phone call that was taped in 2008.

In a notarized letter, Reca granted Laurin permission to narrate his story following his passing. He also gave Laurin permission to record their phone talks for six weeks in late 2008 regarding the crime. Reca provided information on his account of the hijacking in recordings spanning more than three hours. He told his niece Lisa Story about it as well.

Based on the topography that Reca described traveling to reach the drop zone, Laurin deduced that he landed close to Cle Elum, Washington. Laurin found Jeff Osiadacz, who was driving his dump truck near Cle Elum the night of the hijacking, and met a stranger at the Teanaway Junction Café just outside of town after Reca related an incident he had with a dump truck driver at a wayside café after he landed.

Osiadacz obliged with the man’s request to provide his friend’s phone instructions to the café so that they could be picked up. Laurin persuaded former Michigan State Police officer Joe Koenig of Reca’s guilt. Later, Koenig released Getting The Truth: I Am D.B. Cooper, a book about Cooper.

Skepticism has been sparked by these statements. Cle Elum is located far to the north and east of the flight route that Flight 305 is known to have taken, almost 150 miles (240 km) north of the drop zone that most analysts had thought, and much farther away from Tena Bar, the location of some of the ransom money.

Contrary to the FBI’s advertised description of an amateur skydiver at best, Reca was a military paratrooper and private skydiver with hundreds of jumps to his name. Furthermore, Reca did not fit the FBI’s composite image that Laurin and Osiadacz used to justify Osiadacz’s lack of concern at the time.

The FBI responded to the claims made against Reca by stating that it would not be proper to comment on particular tips that were sent to them and that there was currently no evidence that established any suspect’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

William J. Smith

A story in The Oregonian from November 2018 suggested Bloomfield, New Jersey resident William J. Smith (1928–2018) as a suspect. An Army data analyst’s study, which he delivered to the FBI in the middle of 2018, served as the basis for this story. Smith was a World War II soldier and a native of New Jersey.

He joined the US Navy after graduating from high school and offered to train as a combat aircrew member. Following his release, he was employed by the Lehigh Valley Railroad and was impacted by the 1970 bankruptcy of the Penn Central Transportation Company, which at the time was the biggest bankruptcy in American history.

According to the story, he developed a resentment against the corporate world and the transportation industry as a result of losing his pension, along with an unexpected financial necessity. Smith was forty-three when the hijacking occurred.

One possible source of the hijacker’s codename is Ira Daniel Cooper, who is listed among the graduates of his high school who were slain in World War II in the yearbook. According to the analysis, Smith would have been familiar with airplanes and parachutes from his time in the Navy, and his knowledge of railroads would have enabled him to locate railroad lines and board a train to get away from the scene after landing.

The researcher speculated that the metal spiral chips on the clip-on tie may have come from a business that maintained locomotives. Smith’s close buddy Dan Clair, who was stationed at Fort Lewis during the war, could have provided him with knowledge on the Seattle area.

The analyst pointed out that “Dan LeClair” was the identity of the man posing as Cooper in Max Gunther’s 1985 book. Smith and Clair were coworkers at Conrail’s Oak Island Yard in Newark. Smith worked as a yardmaster there until his retirement.

According to the story, a photo of Smith that was posted on the website of the Lehigh Valley Railroad had a “remarkable resemblance” to drawings done by the Cooper FBI. Remarks on tips pertaining to Smith would be unacceptable, according to the FBI.

Duane L. Weber

A veteran of World War II, Duane L. Weber (1924–1995), served time for theft and forgery in at least six prisons between 1945 and 1968. His widow, Jo, put him up as a suspect mainly because of a confession he made on his deathbed three days before to his passing in 1995: “I am Dan Cooper.”

She claimed the name held no meaning for her, but some months later, a friend informed her of its connection to the hijacking. When she went to her local library to do research on Cooper, she came across Max Gunther’s book and her husband’s handwritten notes in the margins. Weber smoked a chainsaw and drank bourbon, much like the hijacking.

Additional circumstantial evidence included his wife’s memory of his tossing a garbage bag upstream of Tina Bar on a trip to Seattle and the Columbia River in 1979.

Though he did not think Weber was Cooper, Himmelsbach stated, “[Weber] does fit the physical description (and) does have the criminal background that I have always felt was associated with the case”.

When Weber’s fingerprints did not match any of those processed from the hijacked airliner, and no other direct evidence was produced to accuse him, the FBI removed him from the case file as an active suspect in July 1998. His DNA later turned up not to match the samples taken from Cooper’s tie.

Similar Hijackings