Benin, commonly known as Dahomey, is a nation in West Africa. It is officially called the Republic of Benin (French: République du Bénin), but it is also referred to as Benin (/bɛˈniːn/ ben-EEN, /bɪˈni\n/ bin-EEN; French: Bénin [benɛ̃], Fon: Benɛ, Fula: Benen). Burkina Faso borders it to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Nigeria to the east, and Togo to the west. Most of its people reside on the southern shore of the Bight of Benin, which is a section of the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean’s northernmost tropical region. The most populated city and commercial hub, Cotonou, serves as the seat of government, while Porto-Novo serves as the capital.

With a land area of 114,763 km2 (44,310 sq mi), Benin is home to over 13 million people, according to estimates from 2021. It is a tropical nation that exports cotton and palm oil and has a largely agricultural economy.

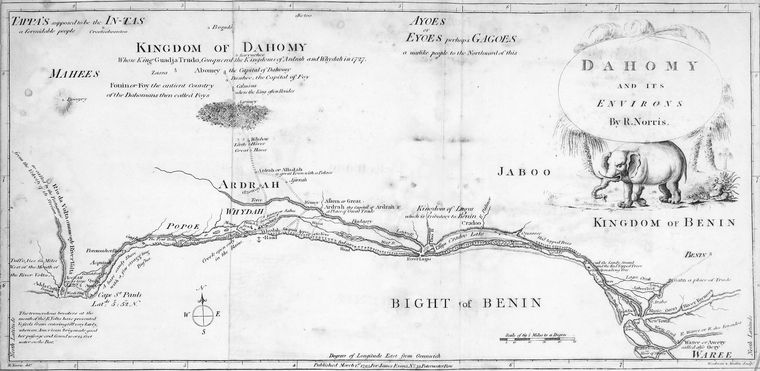

Political entities in the region from the 17th to the 19th centuries included the city-state of Porto-Novo, the Kingdom of Dahomey, and smaller states to the north. Because so many individuals were sold and transported in this area during the Atlantic slave trade to the New World, this area came to be known as the Slave Coast of West Africa in the early 17th century.

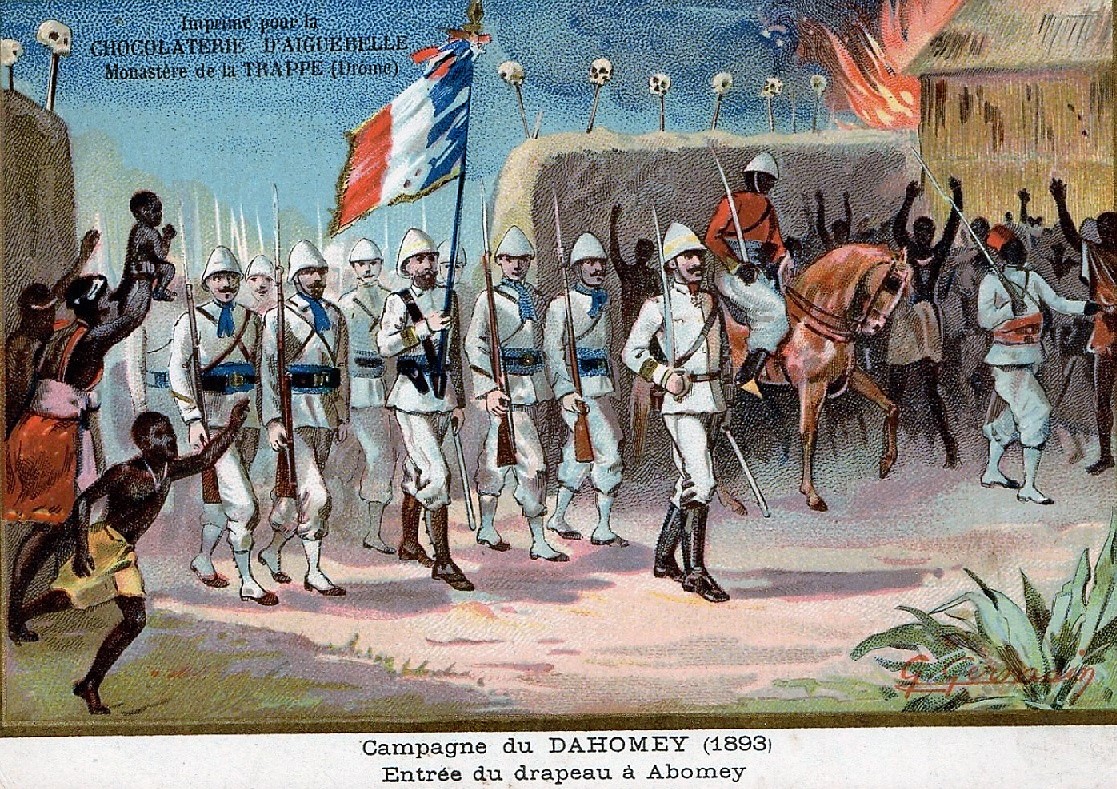

After gaining control of the region in 1894, France annexed French Dahomey and included it in French West Africa. Dahomey fully separated from France in 1960. Benin has seen military takeovers, military regimes, and democratic governments throughout its independence. From 1975 until 1990, the People’s Republic of Benin was a self-described Marxist-Leninist state. The multiparty Republic of Benin took its position in 1991.

While Fon, Bariba, Yoruba, and Dendi are all spoken among the native languages of Benin, French is the official language of the country. Christianity (52.2%) is the most common religious group in Benin, with Islamic (24.6%) and African Traditional Religions (17.9%) following closely behind.

The Community of Sahel-Saharan States, the African Petroleum Producers Association, the Niger Basin Authority, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, the United Nations, the African Union, the Economic Community of West African States, Francophonie, the South Atlantic Peace and Cooperation Zone, and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation all recognize Benin as a member.

Meaning and Origin

Following independence on August 1, 1960, and during French colonial authority, the nation was called Dahomey, after the Kingdom of Dahomey. Due to Dahomey’s association with the Fon people who lived in the southern part of the nation, the country was renamed Benin on November 30, 1975, following a Marxist-Leninist military takeover. The country is called after the Bight of Benin, which borders it. The Kingdom of Benin, which was situated in modern-day Nigeria, is where the bight got its name.

Past Events

Pre-colonial

The modern-day Benin was once made up of several regions with various governmental structures and ethnic groups before 1600. These comprised tribal areas interior (made up of the Bariba, Mahi, Gedevi, and Kabye peoples) and city-states along the coast (mostly of the Aja ethnic group, as well as Yoruba and Gbe peoples).

The Oyo Empire was a military power in the area, mostly to the east of Benin, that carried out raids and demanded tribute from the tribal areas and coastal kingdoms. After the Kingdom of Dahomey, primarily made up of Fon people, was established on the Abomey plateau and started annexing coastal regions in the 17th and 18th centuries, the situation began to shift.

The coastal towns of Whydah and Allada had fallen under the control of King Agaja of the Kingdom of Dahomey by 1727. As a vassal of the Oyo Empire, Dahomey fought against the Oyo-allied city-state of Porto-Novo without going on the offensive. Throughout the colonial and post-colonial eras, Dahomey’s ascent, its rivalry with Porto-Novo, and tribal politics in the northern area endured.

Until they were old enough to enlist in the army, certain younger citizens of Dahomey were trained as apprentices by more experienced soldiers, teaching them the military traditions of the kingdom. Ahosi (the king’s wives), Mino (meaning “our mothers” in Fongbe), or the “Dahomean Amazons” were among the titles given to this elite corps of female soldiers that Dahomey established. Because of its focus on military readiness and success, Dahomey was dubbed “Black Sparta” by European onlookers and 19th-century explorers like Sir Richard Burton.

The Dahomeyan rulers either ritualistically executed their war prisoners during a rite known as the Annual Customs, or sold them into transatlantic slavery. The King of Dahomey sold African captives to European slave dealers for an estimated £250,000 annually by 1750. A thriving slave trade led to the area being dubbed the “Slave Coast”.

Court customs mandating the beheading of some war prisoners from the kingdom’s conflicts reduced the number of slaves transported from the region. By the 1860s, the number had dropped from 102,000 per decade in the 1780s to 24,000 per decade. The Slave Trade Act of 1807, which forbade the transatlantic slave trade started by Britain in 1808 and was later adopted by other nations, contributed to the collapse.

This downward trend persisted until 1885 when the final slave ship left the contemporary Benin Republic for Brazil, a country that had not yet outlawed slavery. The harbor for the slave traffic was the initial purpose of the capital, Porto-Novo, also known as “New Port” in Portuguese.

The Portuguese were interested in carved ivory products, such as hunting horns, spoons, and saltcellars, which were created by Benin’s artisans and sold as exotic commodities outside.

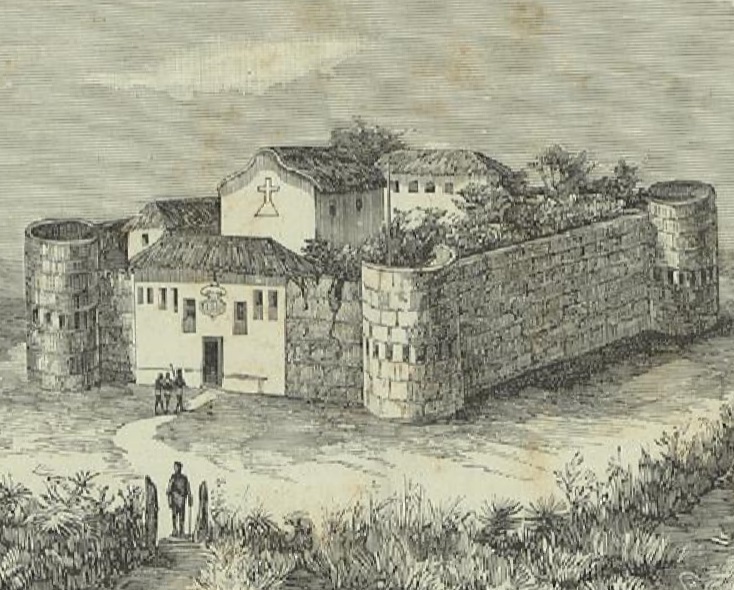

Colonial

Dahomey had “begun to weaken and lose its status as the regional power” by the middle of the 19th century. In 1892, the French occupied the region. The French incorporated the province known as French Dahomey into their broader colonial domain of French West Africa in 1899.

Dahomey “seemed to lack the necessary agricultural or mineral resources for large-scale capitalist development,” which was why France attempted to capitalize on the area. France therefore saw Dahomey as a kind of preserve in case further research turned up riches worth exploiting.

The taking and selling of slaves was forbidden by the French government. Former slaveholders attempted to reinterpret their authority over slaves as authority over land, tenants, and members of their families. This led to a conflict among Dahomeans that “centered around the redistribution of control over land and labor, between 1895 and 1920.” Villages aimed to redraw land and fishery preserve borders. The underlying factional battles over commerce and land control were hardly concealed by religious debates. Great families fought for the leadership of factions.

The Republic of Dahomey received autonomy from France in 1958 and full independence on August 1, 1960, which is observed annually as Independence Day, a national holiday. Hubert Maga was the president who guided the nation toward independence.

Post-colonial

Following 1960, there were coups and changes of governments, with Hubert Maga, Sourou Apithy, Justin Ahomadégbé, and Émile Derlin Zinsou emerging as prominent personalities. The first three each represented a distinct region and ethnic group within the nation. After the 1970 elections were marred by violence, these three decided to establish a Presidential Council.

Maga gave up power to Ahomadégbé on May 7, 1972. After deposing the reigning triumvirate on October 26, 1972, Lt. Col. Mathieu Kérékou took office as president and said that his nation would not “burden itself by copying foreign ideology, and wants neither Capitalism, Communism, nor Socialism”.

He declared on November 30, 1974, that the nation was officially Marxist and that the Military Council of the Revolution (CMR), which had nationalized the banks and petroleum sector, was in charge. He renamed the nation the People’s Republic of Benin on November 30, 1975. Over the course of its existence, the People’s Republic of Benin’s rule saw three phases: a socialist phase (1974–1982), a nationalist phase (1972–1974), and a phase embracing economic liberalism and opening up to Western nations (1982–1990).

Young revolutionaries known as the “Ligmangers” encouraged the government to implement a socialist program in 1974, which included nationalizing key economic sectors, overhauling the educational system, establishing agricultural cooperatives and new local government structures, and waging war against “feudal forces” such as tribalism.

Opposition activities were outlawed by the administration. The National Revolutionary Assembly chose Mathieu Kérékou to be president in 1980, and he was reelected in 1984. He forged alliances with China, North Korea, and Libya and subjected “nearly all” enterprises and economic endeavors to state supervision, leading to a decline in foreign investment in Benin. Kérékou promoted his own proverbs, such as “Poverty is not a fatality,” in an effort to restructure schooling.

Kérékou promoted his own proverbs, such as “Poverty is not a fatality,” in an effort to restructure schooling. By signing contracts to accept nuclear waste from the Soviet Union and then France, the dictatorship was able to finance itself.

Higher economic growth rates were recorded by Benin in the 1980s (15.6% in 1982, 4.6% in 1983, and 8.2% in 1984) until a decline in customs and tax income resulted from the closure of the Nigerian border with Benin. The salaries of civil officials could no longer be paid by the government. When the administration ran out of money to pay its soldiers, protests broke out in 1989. The banking industry failed. Kérékou eventually abandoned Marxism, and he was compelled by a convention to call for elections and the liberation of political prisoners. The Marxist-Leninism system of governance was outlawed in the nation.

On March 1, 1990, the nation’s name was formally changed to the Republic of Benin following the completion of the constitution for the newly established government.

Kérékou became the first President of the African continent to lose office in an election when he was defeated by Nicéphore Soglo in 1991. Kérékou won the 1996 election and went back to ruling. Following the election of 2001, which saw Kérékou win a second term, his opponents accused him of manipulating the results. Kérékou apologized nationally in 1999 for the significant part that Africans had played in the transatlantic slave trade.

The limitations on the age and total terms of candidates set forth in the constitution prevented both Kérékou and former president Soglo from contesting in the 2006 elections. Yayi Boni and Adrien Houngbédji faced a battle in a runoff election on March 5, 2006. After Boni emerged victorious in the runoff election on March 19, she took office on April 6. In order to avoid a runoff election, Boni was reelected in 2011 after receiving 53.18% of the vote in the first round. Since democracy was reinstated in 1991, he was the first president to win an election without a runoff election.

In the March 2016 presidential election, which saw Boni Yayi unable to seek a third term due to constitutional restrictions, billionaire Patrice Talon defeated former prime minister and investment banker Lionel Zinsou in the second round with 65.37% of the vote.

Talon took office on April 6, 2016. Talon announced that he would “first and foremost tackle constitutional reform” on the same day that the Constitutional Court validated the results. He was talking about his proposal to prevent “complacency” by limiting presidents to a single term of five years. He declared that he intended to reduce the number of members in the government from 28 to 16.

Following a presidential election in Benin in April 2021, President Patrice Talon was re-elected with almost 86.3% of the vote. President Talon’s allies gained complete control of parliament as a result of the amendment to the election legislation.

Benin saw the biggest terrorist assault in its history in February 2022.

President Patrice Talon opened an exhibition on February 20, 2022, featuring 26 treasures of holy art that France had restored to Benin, 129 years after colonial soldiers had stolen them.

Characteristics

The south of Benin is home to the vast bulk of its 11,485,000 residents. One can expect to live for 62 years. The Yoruba, who migrated from Nigeria in the 12th century, the Dendi, who arrived in the northeast from Mali in the 16th century, the Bariba and the Fula, the Betammaribe and the Somba in the Atakora Mountains, the Fon in the vicinity of Abomey in the South Central, and the Mina, Xueda, and Aja, who arrived from Togo, are just a few of the approximately 42 African ethnic groups that call this country home.

Ethnic Groups of Benin (2013 Census)

Other African nations, such as Nigerians, Togolese, and Malians, have migrated to Benin. Indians and Lebanese who are interested in trade and commerce are part of the foreign community. A portion of the 5,500 people living in Europe are the staff members of European embassies, overseas assistance missions, humanitarian organizations, and missionary groups.

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1950 | 2000 | 2021 |

| Population | 2,200,000 | 6,800,000 | 13,000,000 |

| ±% | — | +209.1% | +91.2% |

Religion

The two primary faiths in Benin are Islam, which was imported by the Songhai Empire and Hausa traders and is practiced in the provinces of Alibori, Borgou, and Donga, as well as among the Yoruba, who also profess Christianity, and Christianity, which is largely practiced in the south and center. Some people have assimilated the pantheon of Vodun and Orisha into Christianity while maintaining their Vodun and Orisha beliefs. There are also Ahmadiyyas in the nation; they are a 19th-century Islamic group.

Religion in Benin (2020 CIA World Factbook estimate).

48.5% of Benin’s population, as reported in the 2013 census, identified as Christian (25.5% Roman Catholic, 6.7% Celestial Church of Christ, 3.4% Methodist, and 12.9% other Christian denominations), 27.7% as Muslim, 11.6% as Vodun practitioners, 2.6% as followers of other regional traditional religions, 2.6% as followers of other religions, and 5.8% as not affiliated with any religion. According to a government study carried out in 2011–2012 by the Demographic and Health Surveys Program, Muslims made up 22.8% of the population and Christians made up 57.5% (Catholics making up 33.9%, Methodists 3.0%, Celestials 6.2%, and other Christians 14.5%).

In Benin, there were 52.2% Christians, 24.6% Muslims, 17.9% animists, and 5.3% of people who practiced no religion or other religions, according to the most current estimate (2020).

The Yoruba and Tado peoples in the country’s center and south venerate Vodun and Orisha, while indigenous animistic faiths are practiced in the Atakora area. The spiritual hub of Beninese Vodun, or Voodoo, is the town of Ouidah on the country’s central coast.

Education

2015’s projected literacy rate was 38.4% (49.9% for men and 27.3% for women). According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Benin has achieved universal primary education, and in 2013, half of the country’s children (54%) were enrolled in secondary school.

Although there was a period when education was not free, Benin has eliminated school fees and is implementing the suggestions made by its 2007 Educational Forum. Since 2009, the government has allocated nearly 4% of GDP to education. Per the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, state spending on education at all levels was 4.4% of GDP in 2015. Benin contributed 0.97% of GDP, or a portion of this spending, to tertiary education.

The percentage of adults in the 18–25 age group who were enrolled in universities increased from 10% to 12% between 2009 and 2011. Between 2006 and 2011, the number of students enrolled in tertiary education more than quadrupled, rising from 50,225 to 110,181. These figures include students enrolled in non-degree post-secondary diploma programs in addition to those pursuing bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees.

Health

In 2013, the estimated rate of HIV/AIDS among adults in Benin aged 15-49 years was 1.13%. In Benin, malaria poses a significant threat since it is the primary cause of illness and death for children under five years old.

Less than thirty percent of the nation’s population had access to primary healthcare in the 1980s. There were 203 infant deaths in Benin for every 1000 live births. Services for child health care were accessible to one in three moms. This was altered by the Bamako Initiative, which brought community-based healthcare reform and “more efficient and equitable” service delivery.

Benin ranked 26th in the world in terms of maternal mortality as of 2015. A 2013 UNICEF report stated that 13% of women have experienced female genital mutilation. The use of an approach strategy to all facets of healthcare led to improvements in cost and efficiency of care as well as healthcare indicators. Benin has been the subject of Demographic and Health Surveys since 1996.

Geographical

West African terrain is divided into north and south latitudes between 6° and 13°N and longitudes between 0° and 4°E. Nigeria to the east, the Bight of Benin to the south, Burkina Faso and Niger to the north, and Togo to the west form its borders. Approximately 650 kilometers (404 miles) separate the Atlantic Ocean in the south from the Niger River in the north.

The country’s width is around 325 km (202 mi), despite the coastline measuring 121 km (75 mi). Benin’s boundaries are shared by four terrestrial ecoregions: the Guinean forest-savanna mosaic, Nigerian lowland forests, Guinean forest, and West Sudanian savanna. With a mean score of 5.86/10 on the 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index, it was ranked 93rd out of 172 nations worldwide.

From south to north, Benin may be separated into four regions based on differences in height. The lowest region is the sandy coastal plain, with a maximum elevation of 10 m (32.8 ft) and a maximum width of 10 km (6.2 mi). It is covered in marshes and has lakes and lagoons that connect to the ocean all across it.

Beneath the shore is the Guinean forest-savanna mosaic-covered plateaus of southern Benin, which range in elevation from 20 to 200 meters (66 to 656 feet). These plateaus are divided by valleys that cut through them and flow north-south along the Couffo, Zou, and Ouémé Rivers.

Its location leaves it susceptible to climate change. Since most of the nation lives in lower-lying coastal areas, rising sea levels might have an impact on both the people and the economy. More areas in the north will turn into deserts. Around Nikki and Save lies a flatter stretch of terrain interspersed with rocky hills rising to a height of 400 m (1,312 ft).

The Atacora mountain range stretches into Togo and along the northwest boundary. At 658 meters (2,159 feet), Mont Sokbaro is the highest peak. Benin features mangroves, farmland, and woodland remnants. The savanna is peppered with baobab trees and blanketed with prickly brush across the remainder of the nation. Certain woodlands border the sides of rivers. African bush elephants, lions, antelopes, hippopotamuses, and monkeys may be found in the Reserve du W du Niger and Pendjari National Park in the north and northwest of Benin.

Pendjari National Park is one of the lion’s strongholds in West Africa, along with the neighboring Parks Arli and W National Parks in Burkina Faso and Niger. With an estimated 246–466 lions, W-Arli-Pendjari is home to the greatest lion population that remains in West Africa. In the past, Benin has provided a home for the critically endangered African wild dog, Lycaon pictus, which is believed to have been extinct locally.

The coastal area receives 1300 mm, or around 51 inches, of rainfall annually on average. Every year, Benin has two wet and two dry seasons. April through late July is the main rainy season; September through November is a shorter, less severe rainy season. There is a milder dry season from July to September, but the primary dry season runs from December to April. The tropical coast has higher humidity and temperatures. The average high temperature in Cotonou is 31 °C (87.8 °F), while the average low temperature is 24 °C (75.2 °F).

As one travels north over the savanna and plateau toward the Sahel, temperature variations are more pronounced. From December to March, the nation experiences a dry wind from the Sahara known as the Harmattan, which causes the grass to dry up, other plants to become reddish brown, and the skies to seem “overcast” due to a veil of fine dust hanging over the land. Additionally, farmers burn bushes in the fields during this season.

Finance

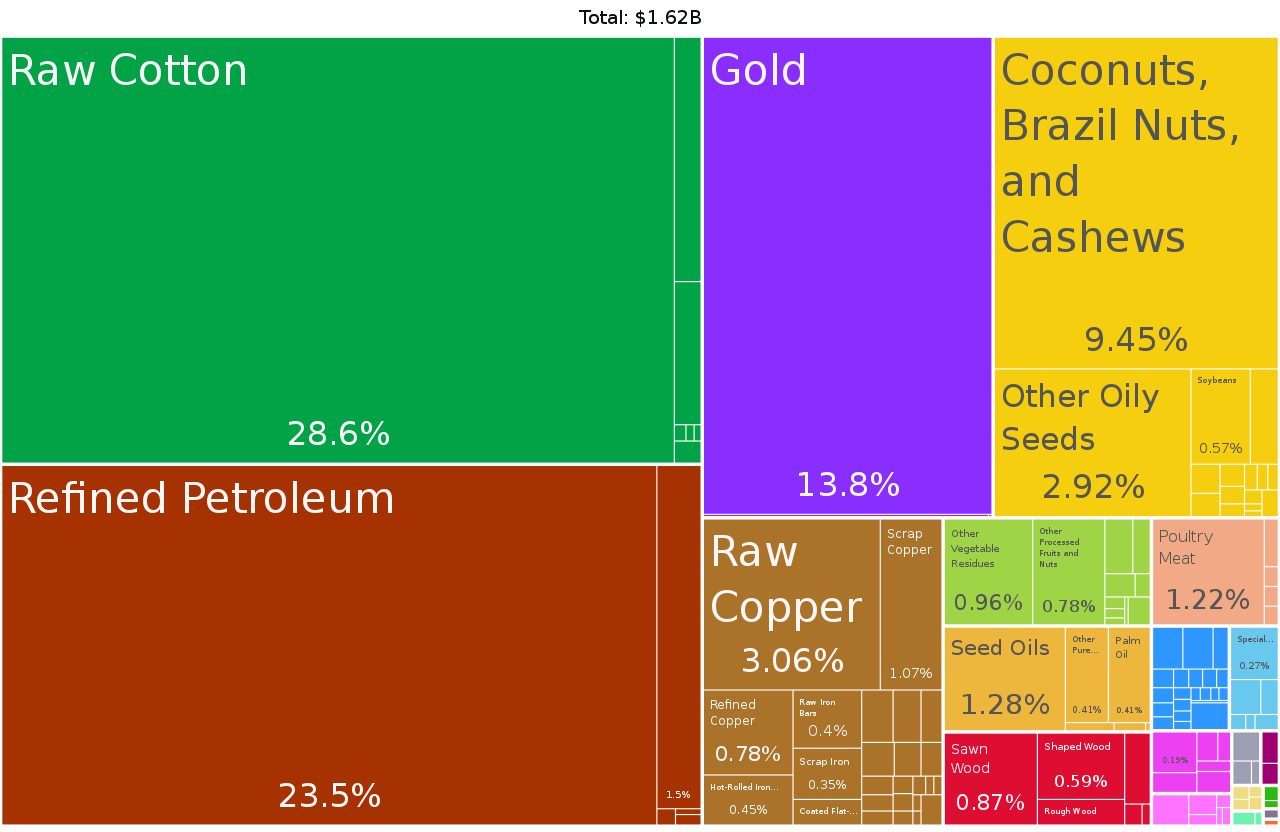

The production of cotton, regional trade, and subsistence farming are the main drivers of the economy. About 80% of official export revenue and 40% of the GDP are derived from the cotton industry.

In 2008 and 2009, real GDP growth was projected to have grown by 5.1% and 5.7%, respectively. The primary engine of development is the agricultural sector, of which cotton is the principal export; services, on the other hand, continue to account for the majority of GDP, mostly as a result of Benin’s advantageous position, which facilitates commerce, transit, and tourism with its surrounding states. 2017 had “positive” macroeconomic circumstances for Benin overall, with a growth rate of about 5.6%. The Port of Cotonou, telecommunications, the cotton sector, and other cash crops were the main drivers of economic expansion.

The Port of Cotonou is an income source, and the government wants to increase the amount of money it receives. Rice, meat and poultry, alcoholic drinks, gasoline plastic materials, specialist mining and excavation machinery, telecommunications equipment, passenger vehicles, toiletries, and cosmetics were among the approximately $2.8 billion in products that Benin imported in 2017. The main exports include timber, cashew, shea butter, cotton cake, cotton seeds, and ginned cotton.

There is less access to biocapacity than the global average. Benin’s biocapacity per capita was 0.9 global hectares in 2016, which was lower than the global average of 1.6 global hectares per person. Benin’s ecological footprint of consumption in 2016 amounted to 1.4 global hectares per person. In other words, they utilize “slightly under double” the amount of biocapacity that Benin has. Benin is experiencing a biocapacity shortage as a result.

Benin benefited from a G8 debt reduction announced in July 2005. The Paris Club and bilateral creditors have improved the external debt position while advocating for more fast structural changes. The government of Benin has taken action to boost domestic power generation since the country’s economic growth is still “adversely affected” by an “insufficient” electrical supply.

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITCU) has observed that there are persistent issues in the informal sector, such as the persistent issue of forced labor, the use of child labor, and the absence of wage equality for women, even while trade unions account for up to 75% of the country’s official workforce. The Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA) has Benin among its members.

The sole international airport and seaport in the nation are located at Cotonou. Two-lane asphalted highways link Benin to its neighboring nations, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Togo. Operators provide mobile phone service throughout the nation. In certain places, ADSL connections are accessible. Since 1998, Benin has been connected to the Internet via satellite links, and since 2001, there has been a single SAT-3/WASC undersea cable. With the launch of the Africa Coast to Europe cable in 2011, relief from “high price” is anticipated.

Since the GDP has grown at a constant pace of 4% to 5% for the past 20 years, poverty has been rising. Benin’s National Institute of Statistics and Economic Analysis reports that the percentage of the population living below the poverty line rose from 36.2% in 2011 to 40.1% in 2015.

Transportation

Benin has access to air, sea, rail, and road transportation. There are 6,787 kilometers of roadway in Benin, of which 1,357 km are paved. There are ten expressways among the nation’s paved roadways. 5,430 km of unpaved road remain after this. Benin is connected to Nigeria to the east and Togo, Ghana, and Ivory Coast to the west via the Trans-West African Coastal Highway. The highway will continue west to seven other countries that are part of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) when work in Liberia and Sierra Leone is completed. Benin is connected to Niger to the north, and from there to Burkina Faso and Mali to the northwest via a paved roadway.

Benin’s rail system is a single track, 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) meter gauge railway spanning 578 km (359 mi). International lines linking Benin to Niger, Nigeria, and Togo have begun to be built; proposals for further links to Burkina Faso and Togo have also been announced. Benin is going to take part in the AfricaRail initiative.

Direct international jet service is available at Cadjehoun Airport in Cotonou to Accra, Niamey, Monrovia, Lagos, Ouagadougou, Lomé, Douala, and other African cities. Cotonou is connected to Paris, Brussels, and Istanbul via direct services.

Culture

Arts

Before French became widely used, Beninese literature was primarily oral. The first Beninese novel, L’Esclave (The Slave), was written in 1929 by Félix Couchoro.

Following independence, local traditional music was blended with French cabaret, American rock, funk and soul, Congolese rumba, Ghanaian highlife, and American rock.

A collaborative event named “Regard Benin” began in the nation in 2010 and is now being carried out by several groups and artists as Biennale Benin. The initiative was transformed into a biennial in 2012 and is now run by a coalition of local groups. Abdellah Karroum was the curator of the 2012 Biennale Benin’s international exhibition and creative program.

Customary names

Some Beninese in the southern part of the nation have names derived from the Akan language that corresponds to the day of the week of their birth. This is a result of the Akwamu and other Akan people’s influence.

Language

In primary schools, the numerous languages of teaching are local languages; French is added later. The only language of teaching in secondary schools is French. Unlike French or English, which use diacritical marks or digraphs for each spoken sound, Beninese languages are “generally transcribed” using a single letter for each phoneme.

This includes Beninese Yoruba, which is written with digraphs and diacritical marks in Nigeria. For example, in Beninese languages, the mid vowels é, è, ô, and o in French are written e, ɛ, o, and ɔ, whereas the consonants transcribed ng and sh or ch in English are written ŋ and c. Digraphs are used for nasal vowels and the labial-velar consonants kp and gb, as in the name of the Fon language, Fon gbe /fõ ɡɡbe/. Diacritics are used as tone indicators. Publications published in that language sometimes combine the orthographies of French and Beninese.

Cuisine

Fresh food is presented with a range of essential sauces in this type of cuisine. Corn is a staple element in southern Benin cuisine, where it’s used to make dough that’s then served with sauces made of tomatoes or peanuts. Consumed foods include cattle, goats, fish, and bush rats. Yams are a mainstay in northern Benin and are typically eaten with the aforementioned sauces.

The people who live in the northern regions consume beef and pig, which is either cooked in sauces or fried in peanut or palm oil. Some recipes call for cheese. Along with fruits including mangoes, oranges, avocados, bananas, kiwi fruit, and pineapples, couscous, rice, and beans are consumed.

It is believed that meals often have a lot of vegetable fat and little meat. Meat is cooked by frying it in peanut or palm oil, while fish is smoked in Benin. Corn flour is ground in grinders to make a dough that is then served with sauces. A dish called “chicken on the spit” calls for roasting chicken on wooden skewers over a fire. To make palm roots more soft, they can occasionally be steeped in a jar with sliced garlic and salt water before being used in recipes. Some people cook on outdoor mud stoves.

Sports

Association football, basketball, tennis, golf, cycling, baseball, softball, and rugby union are the main sports in Benin. Baseball and teqball were brought to the nation in the early years of the twenty-first century.

There are various non-sovereign monarchy in Benin, many of them are descended from kingdoms that existed before colonization (like Arda). Non-sovereign monarchs are mostly ceremonial and deferential to civil and political authority; they have no formal, constitutional function. In spite of this, they have a significant influence on local politics in their respective fields and are frequently courted by Beninese politicians in an attempt to win over voters. Advocate organizations, like the Benin Royal Council, speak for the country’s kings.