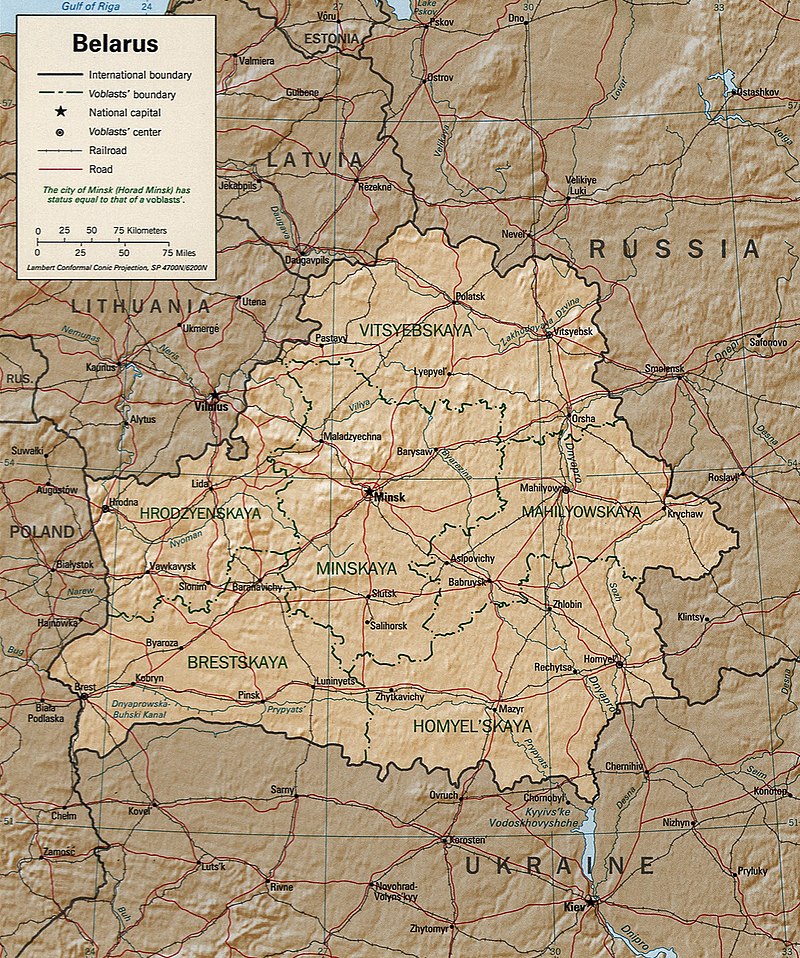

Located in Eastern Europe, Belarus is formally known as the Republic of Belarus. Poland borders it to the west, Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest, Ukraine to the south, and Russia to the east and northeast. With a population of 9.1 million, Belarus has an area of 207,600 square kilometers (80,200 sq mi). Six areas make up the administrative division of this hemiboreal nation. The largest and capital city is Minsk, which is governed independently as a city with a unique status.

The territories of modern-day Belarus were ruled by several nations at different points in time between the Middle Ages and the 20th century, including Kyivan Rus’, the Principality of Polotsk, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Russian Empire.

Following the 1917 Russian Revolution, several nations emerged in the Civil War, vying with one another for legitimacy. This led to the establishment of the Byelorussian SSR, which in 1922 became one of the founding member republics of the Soviet Union. Following the 1918–1921 Polish-Soviet War, Belarus lost about half of its territory to Poland.

After the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, several areas of the Second Polish Republic were reintegrated into Belarus, giving it its current borders, which were formalized after World War II. Belarus lost over 25% of its people and half of its economic resources as a result of military actions carried out during World War II.

Along with the Soviet Union, the Byelorussian SSR joined the UN as a founding member in 1945. A broad and heterogeneous anti-Nazi insurgent movement flourished in the republic, controlling politics well into the 1970s and guiding Belarus’s economic transition from one based on agriculture to one based on industry.

On July 27, 1990, the republic’s parliament declared Belarus’s statehood; on August 25, 1991, as the Soviet Union broke apart, Belarus became an independent nation. Alexander Lukashenko has been the president of Belarus ever since the country’s first and only free election following independence in 1994 when a new constitution was adopted.

Lukashenko leads an extremely centralized authoritarian regime. In comparison to other countries, Belarus has low levels of press freedom and civil rights. Many policies from the Soviet era have been maintained, including state control of significant portions of the economy.

The only nation in Europe still using the death penalty is Belarus. A deal for further cooperation was agreed by Belarus and Russia in 2000, creating the Union State.

In addition to joining the CIS, CSTO, EAEU, OSCE, and Non-Aligned Movement, the nation has been a member of the UN since its creation. Although it hasn’t indicated that it wants to join the EU, it nonetheless keeps up bilateral ties with the organization and takes part in the Baku Initiative.

Meaning and Origin

The word “Belaya Rus,” or “White Rus,” and the name Belarus are intimately associated. Many have disputed the origin of the moniker White Rus. According to an ethno-religious explanation, the name “Black Ruthenia,” which was mostly inhabited by pagan Balts, was instead used to refer to the area of the ancient Ruthenian regions inside the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that had been occupied primarily by Slavs who had converted to Christianity early on.

Another interpretation of the name makes reference to the white attire that the Slavic residents of the area wear. According to a third account, the old Rus’ regions (Polotsk, Vitebsk, and Mogilev) that the Tatars did not overrun were known as the “White Rus.” According to a fourth idea, Belarus was the western region of Russia from the ninth to the thirteenth century, and white was connected with the west.

Belarus is frequently referred to as White Russia or White Ruthenia because the word Rus is frequently confused with its Latin equivalents, Russia and Ruthenia. The term initially occurred in German and Latin medieval literature; the Lithuanian grand duke Jogaila and his mother were imprisoned at “Albae Russiae, Poloczk dicto” in 1381, according to Jan of Czarnków’s chronicles.

The term “White Russia” was originally used to describe Belarus in the late 16th century by Sir Jerome Horsey, an Englishman well-known for his intimate ties to the Russian royal court. The phrase was used by the Russian tsars in the 17th century to refer to the territories that were annexed from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

During the Russian Empire, the Russian Tsar was referred to as “the Tsar of All the Russias” because Russia, or the Russian Empire, was made up of three parts: the Great, Little, and White. The term Belorussia (Russian: Белору́cсия), the latter part spelled and stressed differently from Росси́я, Russia, first appeared. According to this, all of the people and all of the areas are Russian; in the case of the Belarusians, they are just other forms of the Russian people.

Given that it also denoted the name of the armed force that opposed the red Bolsheviks, the phrase “White Russia” created considerable misunderstanding following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. The name “Belorussia” was accepted as a component of the national identity during the Byelorussian SSR. During the interwar period, Byelorussia gained widespread usage in the areas of Białystok and Grodno, which were under Polish authority in western Belarus.

Only in 1991 was the term Byelorussia legally used (its names in other languages, such as English, are based on the Russian version). The official name of the nation is the Republic of Belarus (also known as Respublika Belarus, Рэcпубліка Беларусь, and Республика Беларусь). The term Belorussia is still widely used in Russia.

Belarus is sometimes referred to as Gudija in Lithuanian, in addition to Baltarusija (White Russia). It’s unclear where the word “Gudija” came from. According to one theory, the word comes from the Old Prussian name Gudwa, which is connected to the form Żudwa, which is a perverted form of Sudwa, Sudovia.

In turn, one of the Yotvingians’ names is Sudovia. Another theory links the name to the Gothic Kingdom, which in the fourth and fifth centuries ruled over portions of what is now Belarus and Ukraine. Goths named themselves Gutans and Gytos, which are near Gudija.

Another theory is based on the notion that Gudija, which means “the other” in Lithuanian, may have been a historical term used by Lithuanians to describe anyone who did not speak the language.

Past Events

Earlier times

In what is now Belarus, the Bandkeramik was controlled from 5000 to 2000 BC, and by 1,000 BC, the region was inhabited by the Cimmerians and other pastoralists. Later, around the start of the first millennium, the Zarubintsy civilization expanded widely.

Furthermore, remnants of the Dnieper–Donets civilization have been discovered in Belarus and certain regions of Ukraine. In the third century, Baltic tribes became the first people to dwell in the area permanently. The region was conquered by the Slavs in the fifth century. Although the Balts’ lack of military organization contributed to the takeover, their peaceful absorption into Slavic culture was slow.

Around 400–600 AD, Asian invaders—among them the Huns and Avars—swept across the region, but they were unable to drive out the Slavic population.

Kievan Rus’

The area that is now Belarus was included into Kievan Rus, a sizable East Slavic nation controlled by the Rurikids, in the ninth century. After Yaroslav the Wise’s death in 1054, the state broke apart into several principalities. One of the more important historical occurrences of the time was the Battle of the Nemiga River in 1067, which is regarded as the creation date of Minsk.

A large Mongol invasion in the 13th century practically destroyed or badly damaged several early monarchies, but the regions that would later become modern-day Belarus spared the brunt of the attack and joined the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The annals confirm Polotsk and Lithuania’s cooperation and joint foreign strategy for decades, although there are no sources indicating a military takeover.

Belarusian territories became economically, politically, and ethnoculturally united after being included by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Nine of the principalities that the duchy possessed were populated by a people who would later become Belarusians. The duchy fought in many military operations during this period, most notably the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, where it allied with Poland to defeat the Teutonic Knights and take control of the northwest frontiers of Eastern Europe.

In 1486, the Muscovites, under the leadership of Ivan III of Russia, launched military expeditions in an effort to conquer the old Kievan Rus’ territory, which included the areas that are now Belarus and Ukraine.

Lithuanian-Polish Commonwealth

The rulers of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland were married on February 2, 1386, forming a personal union. The Union of Lublin in 1569 initiated the processes that ultimately led to the establishment of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The progressive Polonization of both Lithuanians and Ruthenians gathered steady impetus in the years after the unification. Both Catholicism and the Polish language gained ground in society and culture. In 1696, Ruthenian was outlawed as an administrative language, and Polish took its place as the official tongue.

The Ruthenian peasants, however, kept speaking in their own tongue. Additionally, the Poles founded the Belarusian Byzantine Catholic Church with the intention of assimilating Orthodox Christians into the See of Rome. Through the Union of Brest in 1595, the Belarusian church maintained its Byzantine liturgy in Church Slavonic while gaining full communion with the Latin Church.

Empire of Russia

With the Third Partition of Poland by Imperial Russia, Prussia, and Austria in 1795, the union between Poland and Lithuania came to an end. The areas of Belarus that the Russian Empire had taken over during Catherine II’s rule were included in the Belarusian Governorate (Russian: Белoрусское генерал-губернаторство) in 1796 and remained under its control until the German Empire occupied them during World War I.

National cultures were suppressed by Nicholas I and Alexander III, whose Russification measures—which included Belarusian Uniates’ conversion to Orthodox Christianity—replaced their Polonization initiatives. While elementary school education with Samogitian literacy was permitted in adjacent Samogitia, the use of the Belarusian language in classrooms was outlawed.

Nicholas I launched a campaign against Belarusian publications, outlawed the use of the Belarusian language in public schools, and attempted to persuade Poles who had converted to Catholicism to return to Orthodoxy as part of a Russification push in the 1840s.

Economic and cultural pressures culminated in a rebellion in 1863 that was spearheaded by Konstanty Kalinowski, sometimes referred to as Kastus. Following the unsuccessful uprising, the Russian authorities restored Cyrillic writing to Belarusian in 1864, and until 1905, the Russian government did not allow the printing of any documents in Belarusian.

On March 25, 1918, under German occupation, Belarus declared its independence and established the Belarusian People’s Republic during the negotiations for the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The Polish-Soviet War broke out shortly after, dividing Belarus’s territory between Soviet Russia and Poland. Since then, the Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic has continued to function as a government in exile; in fact, it is presently the longest-serving government in exile in the world.

States in their early years and the interwar years

The first effort to establish an independent Belarusian state under the name “Belarus” was the Belarusian People’s Republic. The kingdom did not survive despite great efforts; this was mainly due to the area being continuously ruled by the Imperial Russian and German armies throughout World War I, followed by the Bolshevik Red Army.

Although it barely lasted from 1918 to 1919, it set the stage for Belarus to become a state. The nomenclature was presumably determined by the fact that the leading figures in the recently established administration had their education at tsarist universities, which therefore prioritized the ideology of West-Russianism.

From left to right, seated are Vasil Zacharka, Jan Sierada, Jazep Varonka, and Aliaksandar Burbis.

Arkadź Smolič, Pyotra Krecheuski, Kastuś Jezavitaŭ, Anton Ausianik, and Liavon Zayats are standing, left to right.

The final effort to return Lithuania to its former confederacy state was the short-lived Republic of Central Lithuania, which was also intended to establish Lithuania Upper and Lithuania Lower. Following the staged uprising by soldiers of the Polish Army’s 1st Lithuanian-Belarusian Division led by Lucjan Żeligowski, the republic was established in 1920.

For eighteen months, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania centered on Vilna (Lithuanian: Vilnius, Polish: Wilno), and acted as a buffer state between Lithuania, which claimed the region, and Poland, on whose behalf it depended.[58] Following several postponements, the disputed election was held on January 8, 1922, and Poland conquered the province.

Later, in his memoirs published in London in 1943, Łeligowski denounced Poland’s annexation of the Republic, the suppression of Belarusian schools, and Poland’s overall contempt for Marshal Józef Piłsudski’s ambitions for confederation.

The Socialist Soviet Republic of Byelorussia (SSRB) was established in January 1919 for a brief period of time, governing a portion of Belarus under Bolshevik Russian rule. It lasted only two months before merging with the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (LSSR) to become the Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Belorussia (SSR LiB), which lost sovereignty of its territories by August.

In July 1920, the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR) was established.

After the war concluded in 1921, the disputed regions were divided between Poland and the Soviet Union, and in 1922 the Byelorussian SSR joined the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics as a founding member.

Famine and political persecution resulted from Soviet agricultural and economic policies in the 1920s and 1930s, including collectivization and five-year plans for the national economy.

The contemporary nation of Belarus’s west continued to be a member of the Second Polish Republic. Tensions between the growing nationalistic Polish government and different increasingly separatist ethnic minorities began to rise after an initial period of liberalization; the Belarusian minority was no exception.

The Polish National Democracy, headed by Roman Dmowski, who promoted denying Belarusians and Ukrainians the right to a free national development, served as an inspiration for and impact on the polonization movement. The Belarusian Peasants’ and Workers’ Union was outlawed in 1927, and the Polish government’s critics faced punishment from the authorities. However, Belarusians experienced fewer repressions than the Ukrainian minority since they were less politically informed and engaged than the latter.

Following Piłsudski’s death in 1935, a fresh wave of repression was unleashed against the minorities, resulting in the closure of several Orthodox churches and Belarusian schools. The Belarusian language was not to be used. The leadership of Belarus was detained at Bereza Kartuska jail.

Second World War

Two weeks earlier, the German invasion of Poland had triggered the start of World War II, and two weeks later, the Soviet Union invaded and conquered eastern Poland. The Byelorussian SSR acquired and merged the Western Belorussian regions. The areas, inhabited by a mixed population of Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Jews, were formally taken over by the Soviet-controlled Byelorussian People’s Council on October 28, 1939, at Białystok. In 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. The first significant combat of Operation Barbarossa took place during the defense of Brest Fortress.

The Soviet republic most severely damaged in World War II was the Byelorussian SSR, which the Germans occupied until 1944. In order to provide Germans with greater living areas in the East, the German Generalplan Ost called for the eradication, deportation, or slavery of most or all Belarusians. The majority of Western Belarus was included in the Reichskommissariat Ostland in 1941; nonetheless, the German government permitted local allies to establish the Belarusian Central Council as a client state in 1943.

There were several different guerrilla formations in Belarus during World War II, including Soviet, Polish, and Jewish partisans. Belarus has continued to refer to itself as the “partisan republic” since the 1970s. Belarusian partisan formations made up a sizable portion of the Soviet partisans, and these partisans now constitute a fundamental component of the national character of Belarus.

Many former Soviet partisans, including Pyotr Masherov and Kirill Mazurov, who served as the Communist Party of Byelorussia’s First Secretary, joined the government after the war. Former partisans made up nearly the whole Belarusian administration until the late 1970s.

Many media have been produced on the Belarusian partisans, such as the novels Ales Adamovich and Vasil Bykaž and the 1985 film Come and See.

Belarus was ravaged by the conflict on the Eastern Front and the German occupation from 1941 to 1944. In that period, over a million structures, 85% of the republic’s industrial capacity, and 209 of the 290 towns and cities were destroyed. It was claimed that 2.2 million local residents had perished in the conflict, with 810,000 of them being fighters, and some of them being foreign nationals.

This amount was a startling 25% of the prewar population. Some even increased the number to 2.7 million in the 1990s. During the Holocaust, Belarus’ Jewish community suffered greatly and never fully recovered. It took until 1971 for Belarus’s population to return to its pre-war level. Belarus suffered a severe economic setback as well, losing nearly all of its financial resources.

Post-war

The Curzon Line, which was suggested in 1919, was followed by redrawing the borders of Poland and the Byelorussian SSR.

Sovietization was a program put into place by Joseph Stalin to keep the Byelorussian SSR apart from Western influences. As part of this approach, Russians from other Soviet regions were sent and given important posts in the government of the Byelorussian SSR. The cultural hegemony campaign of Stalin was carried out by Nikita Khrushchev following his death in 1953, with the slogan “The sooner we all start speaking Russian, the faster we shall build communism.”

Former Soviet partisans, such as First Secretaries Kirill Mazurov and Pyotr Masherov, controlled Belarusian politics between Stalin’s death in 1953 and 1980. Under Mazurov and Masherov’s direction, Belarus quickly industrialized and went from being one of the poorest to one of the richest republics in the Soviet Union. The majority (70%) of the radioactive fallout from the 1986 explosion at the Chornobyl power station, which was 16 km over the border in the adjacent Ukrainian SSR, was transferred to the Byelorussian SSR.

Political liberalization sparked a national renaissance by the late 1980s, during which the Belarusian Popular Front emerged as a significant movement in favor of independence.

Independence

Elections for seats in the Byelorussian SSR’s Supreme Soviet were held in March 1990. With the issuance of the Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic on July 27, 1990, Belarus proclaimed its independence, despite the opposition candidates, who were primarily affiliated with the pro-independence Belarusian Popular Front, winning just 10% of the seats.

Extensive strikes broke out in April 1991. On August 25, 1991, the name of the nation was changed to the Republic of Belarus with the backing of the Communist Party of Byelorussia. On December 8, 1991, in the Białowieża Forest, Stanislav Shushkevich, the chairman of the Supreme Soviet of Belarus, met with Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine and Boris Yeltsin of Russia to formally announce the breakdown of the Soviet Union and the creation of the Commonwealth of Independent States.

The Belarusian Popular Front began its campaign in January 1992, advocating for early elections that year—two years ahead of schedule. About 383,000 signatures, or 23,000 more than what was then legally needed to be put to a vote, had been gathered by May of that year for a petition to conduct the referendum. In spite of this, there was a six-month delay in the Supreme Council of the Republic of Belarus meeting that was supposed to determine the date of the referendum.

However, the Supreme Council denied the petition due to significant anomalies even though there was no evidence to support such a claim. The Supreme Council elections were scheduled for March 1994. By 1993, a new parliamentary election legislation had not been passed.

The Party of Belarusian Communists, which at the time dominated the Supreme Council and was primarily against political and economic change, was blamed for disputes surrounding the vote. There were claims that some of the lawmakers were against Belarusian independence.

The Lukashenko period

In March 1994, a national constitution was ratified, designating the President of Belarus as the prime minister. Alexander Lukashenko, who was unknown before the two-round presidential election on June 24, 1994, and July 10, 1994, sprang to national notoriety. He defeated Vyacheslav Kebich, who won 14% of the vote, with 45% of the vote in the first round and 80% in the second. After Belarus gained its independence, these were the country’s first and only free elections.

Numerous economic disagreements between Belarus and its main economic partner, Russia, occurred in the 2000s. The first one was the energy dispute between Russia and Belarus in 2004 when Russian energy giant Gazprom stopped importing gas into Belarus due to pricing disputes. Gazprom’s claims that Belarus was stealing oil from the Druzhba pipeline, which passes through Belarus, were at the heart of the 2007 energy conflict between Russia and Belarus. Two years later, Belarus was forced to prohibit the import of dairy products from Russia as a result of the so-called Milk War, a trade dispute that began when Russia demanded that Belarus acknowledge the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

The concentrated economic control exercised by Lukashenko’s administration caused a catastrophic economic crisis in Belarus in 2011, resulting in 108.7% inflation. The 2011 Minsk Metro bombing, which left 204 people injured and 15 dead, happened around the same time. In 2012, two suspects were shot to death after they admitted to being the culprits and were apprehended in less than two days.

The UN Security Council’s extraordinary statement denouncing “the apparent terrorist attack” raised doubts about the official account of events as released by the Belarusian government, hinting at the possibility that the government may have been responsible for the explosion.

Following the contentious 2020 Belarusian presidential election,[96] in which Lukashenko ran for a sixth term in office, widespread demonstrations broke out around the nation. The primary opposition candidate, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, and other members of the Belarusian opposition have been granted a home in Vilnius by the Lithuanian government. The neighboring nations, Poland and Lithuania, do not acknowledge Lukashenko as the legitimate president of Belarus.

Neither the European Union nor the United States nor Canada acknowledged Lukashenko as the rightful president of Belarus. Because of the fraudulent election and political repression that have occurred during the country’s ongoing demonstrations, Belarus has been subject to sanctions from the European Union, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

In 2022, more sanctions were put in place as a result of the nation’s involvement and cooperation with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which was partially orchestrated by Russian forces using Belarusian territory. These comprise private persons employed in the state-owned enterprise industrial sector in addition to corporate offices and certain government personnel. Joining the sanctions regime to cut Belarus off from the global supply chain are Norway and Japan. Also subject to limitations are the majority of Belarusian banks.

Geographical

Between latitudes 51° and 57° N and longitudes 23° and 33° E is where Belarus is located. Its length is 650 km (400 mi) from west to east and 560 km (350 mi) from north to south. It is mostly level, landlocked, and home to extensive wetlands. Belarus has woods covering almost 40% of its land. The nation is located in the Central European mixed forest ecoregion and the Sarmatic mixed forest ecoregion.

Belarus has 11,000 lakes and several streams. The Neman, Pripyat, and Dnieper are the three principal rivers that flow through the nation. The Pripyat flows eastward to the Dnieper, whereas the Neman flows westward into the Baltic Sea. The Dnieper then flows southward towards the Black Sea.

At 345 meters (1,132 feet), Dzyarzhynskaya Hara (also known as Dzyarzhynsk Hill) is the highest point, and the Neman River is the lowest point at 90 meters (295 feet). Belarus is situated 160 meters (525 feet) above sea level on average. The temperature ranges from -4 °C (24.8 °F) in the southwest (Brest) to -8 °C (17.6 °F) in the northeast (Vitebsk) in January minimums. The summers are cool and humid, with an average temperature of 18 °C (64.4 °F). Rainfall in Belarus ranges from 550 to 700 mm (21.7 to 27.6 in) on average each year. The nation is situated in the area where continental and marine climates converge.

Peat deposits, trace amounts of oil and natural gas, granite, dolomite (limestone), marl, chalk, sand, gravel, and clay are examples of natural resources. The 1986 Chornobyl nuclear accident in neighboring Ukraine sent nearly 70% of its radioactive fallout into Belarus, affecting around 5% of the country’s land, mostly farms and woods in the country’s southeast. In order to lower the amounts of cesium-137 in the soil, the United Nations and other organizations have worked to lower the radiation levels in the impacted areas. One such method is the use of cesium binders and rapeseed farming.

Belarus shares borders with Russia to the north and east, Latvia to the north, Lithuania to the northwest, Poland to the west, and Ukraine to the south. Belarus’s borders with Latvia and Lithuania were established by treaties in 1995 and 1996, and in 2009, Belarus accepted a treaty from 1997 that established the boundary with Ukraine. Final boundary delineation documents were confirmed by Belarus and Lithuania in February 2007.

Finance

Although Belarus is a developing nation, it has a “very high” human development index ranking—it is ranked 60th out of all nations. With one of the lowest Gini coefficients for measuring the allocation of national resources, it is among the most equitable nations globally, and its GDP per capita ranks 82nd.

With the manufacturing sector accounting for more than two-thirds of the GDP in 2019, the manufacturing sector contributed 31% of GDP. 34.7% of workers were working in manufacturing. In comparison to the overall economy, the manufacturing sector is expected to increase by only 2.2% in 2021. Potatoes and cow byproducts, such as meat, are significant agricultural goods.

Trade

Belarus trades with more than 180 nations. As of 2007, Belarus’s principal commercial partners were the EU nations, with 25% of exports and 20% of imports, and Russia, which accounted for around 45% of exports and 55% of imports (which included petroleum).

The EU slapped trade sanctions on Belarus in April 2022 due to their assistance of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In August 2023, the restrictions were tightened and prolonged. These penalties are on top of the ones that were put in place after Lukashenko’s 2020 “election” was rigged.

When the Soviet Union broke apart in 1991, Belarus was the richest member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and one of the most industrially developed nations in the world in terms of GDP. 39.3% of Belarusians worked for state-run businesses in 2015, 57.2% for private businesses (in which the government has a 21.1% share), and 3.5% for international businesses.

Belarus’s top exports in 1994 were energy items, agricultural products, and heavy machinery (particularly tractors). In terms of trade, Belarus participated in the Eurasian Economic Community, the Union with Russia, and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The 1990s saw a sharp decline in industrial production as a result of declining investment, imports, and trading partner demand for Belarusian goods.

The GDP of the nation started to increase only in 1996, making it the former Soviet republic with the quickest economic recovery. GDP was estimated to have been US$83.1 billion in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms in 2006, or around $8,100 per person. The GDP grew by 9.9% in 2005, while the average annual inflation rate was 9.5%. In 2023, Belarus came in at number 80 on the Global Innovation Index.

Under Lukashenko’s direction, Belarus has avoided the widespread privatizations observed in other former Soviet republics and retained government ownership over important sectors after the breakup of the Soviet Union.

In 1993, Belarus submitted an application to join the World Trade Organization. Belarus lost its position as an EU Generalized System of Preferences member on June 21, 2007, and as a result, tariff rates were raised to their previous levels as most favored countries. This was due to Belarus’s inability to respect worker rights, notably the passage of legislation prohibiting unemployment or working outside state-controlled industries.

Workplace

There are almost 4 million persons in the workforce, with slightly more women than males. Approximately 25% of the workforce worked in industrial factories in 2005. Agriculture, manufacturing sales, selling products, and education all have high employment rates. Government figures from 2005 show that the unemployment rate was 1.5%. Two-thirds of the 679,000 jobless Belarusians were female. Since 2003, there has been a decrease in the unemployment rate, and the total employment rate is at its highest point since data were first collected in 1995.

Money

The Belarusian ruble is the country’s currency. The currency underwent two rounds of redenomination since it was first established in May 1992 as a replacement for the Soviet ruble. On December 27, 1996, the Republic of Belarus released its first set of coins. Reintroduced with new values in 2000, the ruble has been in circulation ever since.

The Belarusian National Bank stopped linking the currency to the Russian ruble in 2007. Russia and Belarus, as members of the Union, have spoken of implementing a common currency that is similar to the euro. This resulted in a proposal to replace the Belarusian ruble with the Russian ruble (RUB) beginning on January 1, 2008.

The value of the ruble fell by 56% compared to the US dollar on May 23, 2011. On the illegal market, the devaluation was far as severe, and people were rushing to convert their rubles into dollars, euros, durable goods, and tinned goods as the financial collapse appeared near. Belarus asked the International Monetary Fund for an economic rescue package on June 1, 2011.

In July 2016, the Belarusian ruble was replaced by a new currency, the new Belarusian ruble (ISO 4217 code: BYN), at a rate of 1:10,000 (10,000 old rubles = 1 new ruble). Series 2000 notes and coins may be exchanged for Series 2009 from 1 January 2017 until 31 December 2021. The old and new currencies were in concurrent circulation from 1 July to 31 December 2016.

One may argue that this redenomination is an attempt to combat the high pace of inflation. In an effort to address food inflation, Lukashenko outlawed price hikes on October 6, 2022. Belarus made copyright violations of media and intellectual property produced by “unfriendly” foreign countries lawful in January 2023.

The Central Bank (National Bank of the Republic of Belarus) and 25 commercial banks make up the two tiers of Belarus’s banking system.

Demographics

9.41 million people called Belarus home as of the 2019 census, with ethnic Belarusians making up 84.9% of the country’s overall population. Russians (7.5%), Poles (3.1%), and Ukrainians (1.7%) are examples of minority groups. About 50 persons live in each square kilometer (127 in each square mile) of Belarus, while 70% of the population resides in metropolitan areas.

The population of Minsk, the capital and largest city of the country, was 1,937,900 in 2015. As the capital of the Gomel Region, Gomel is the second-largest city with 481,000 residents. Mogilev (365,100), Vitebsk (342,400), Grodno (314,800), and Brest (298,300) are some of the other major cities.

Belarus has a negative natural growth rate and a negative population growth rate, similar to many other Eastern European nations. Belarus had a 0.41% population loss and a 1.22 fertility rate in 2007, which is much lower than the replacement rate. Belarus has a net migration rate of +0.38 per 1,000, meaning that there is somewhat more immigration than emigration there. 69.9% of Belarusians are between the ages of 14 and 64 as of 2015; 15.5% of the country’s population is under 14 and 14.6% is 65 or older.

The population is aging as well; in 2050, the 30-to-34-year-old median age is predicted to increase to between 60 and 64. In Belarus, there are around 0.87 men for every woman. The average life expectancy is 72.15 years, with women living 78.1 years and males 66.53 years. In Belarus, more than 99% of people over the age of 15 are literate.

Religion

As per the results of the November 2011 census, 58.9% of Belarusians identified as religious; around 82% of them were Eastern Orthodox: Although there is a little Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church as well, Eastern Orthodox in Belarus are mostly members of the Belarusian Exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Protestantism comes in several varieties, and Roman Catholicism is primarily popular in western areas. Greek Catholicism, Judaism, Islam, and Neo-Paganism are also practiced by minorities. In general, 48.3% of people identify as Orthodox Christians, 41.1% as agnostics, 7.1% as Roman Catholics, and 3.3% as adherents of other faiths.

The Catholic minority in Belarus is made up of a mixture of Belarusians and the Polish and Lithuanian minorities living in the country’s western regions, particularly the area surrounding Grodno. According to President Lukashenko, the “two main confessions in our country” are those of Orthodox and Catholic Christians.

A significant hub for European Jews in the past, Belarus had 10% of its people of Jewish descent. However, the Holocaust, deportations, and emigration have diminished the Jewish population since the mid-1900s, to the point that it is currently a very small minority of fewer than 1%.

The majority of the nearly 15,000 Lipka Tatars are Muslims. The Constitution’s Article 16 states that there is no official religion in Belarus. Even if the same article guarantees the right to freedom of worship, religious groups that are thought to be disruptive to the state or social order may be outlawed.

Languages

The two official languages of Belarus are Russian and Belarusian; of these, 70% of the population speaks Russian at home, while 23% speaks Belarusian, which is the official first language. Eastern Yiddish, Polish, and Ukrainian are also spoken by minorities. While just 41.5% of people speak it as their mother tongue, 53.2% of Belarusians speak it as their first language, despite being less common than Russian.

After Alexander Lukashenko was elected, the majority of large-city schools switched from teaching Belarusian to Russian. Between 1990 and 2020, the yearly distribution of literature written in Belarusian also saw a notable decline.

Traditions

Arts and Literature

Annual cultural events like Vitebsk’s Slavianski Bazaar, which features Belarusian actors, singers, writers, and painters, are sponsored by the Belarusian government. Many state holidays, notably in Vitebsk and Minsk, attract large crowds, and festivities like military parades and pyrotechnics are common. These include Victory Day and Independence Day. Events that support Belarusian arts and culture both domestically and internationally are funded by the government’s Ministry of Culture.

Religious texts from the 11th to the 13th centuries, including Cyril of Turaw’s poetry from the 12th century, served as the foundation for Belarusian literature.

Francysk Skaryna, a citizen of Polotsk, translated the Bible into Belarusian around the 16th century. It was the first book printed in Belarus or any place in Eastern Europe, having been produced in Prague and Vilnius somewhere between 1517 and 1525.

The late 19th century saw the beginning of the modern age in Belarusian literature, with Yanka Kupala emerging as a notable author. A number of writers from that era, including Ōmitrok Biadula, Yakub Kolas, Kazimir Svayak, Uładzimir Žyłka, and Maksim Haretski, wrote for Nasha Niva, a Belarusian-language publication that was once published in Vilnius but is currently published in Minsk.

Cultural issues in the Republic were taken over by the Soviet government upon Belarus’s integration into the Union. In the newly established Byelorussian SSR, a “Belarusianization” strategy was initially implemented. In the 1930s, this approach was reversed, and most notable nationalist and intellectual figures in Belarus were either banished or executed in Stalinist purges. Up to the Soviet occupation in 1939, Polish-held territory was the only place where literature could flourish freely. Following the Nazi occupation of Belarus, a number of poets and writers fled the country and did not return until the 1960s.

Novels by Vasil Bykaž and Uladzimir Karatkievich published in the 1960s were the last significant rebirth of Belarusian literature. Ales Adamovich was a well-known writer who dedicated his career to making people aware of the tragedies the nation has experienced. He was described as “her main teacher, who helped her to find a path of her own” by Svetlana Alexievich, the 2015 Nobel Prize laureate in Literature and native of Belarus.

The rich heritage of folk and religious music makes up the majority of Belarusian music. Folk music traditions in the nation date back to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s existence. Polish composer Stanisław Moniuszko lived in Minsk during the 19th century and wrote chamber music and operas.

He collaborated on the opera Sialanka (Peasant Woman) with Belarusian poet Vintsent Dunin-Martsinkyevich when he was there. Major Belarusian cities had their own opera and ballet companies toward the close of the 1800s. M. Kroshner’s ballet Nightingale, which debuted at the National Academic Vialiki Ballet Theatre in Minsk, was the first produced in Belarus during the Soviet era.

Following World War II, Belarusian music centered on the suffering of the people or on those who fought for their country. Belarusian composers looked to Anatoly Bogatyrev, the man behind the opera In Polesye Virgin Forest, as their “tutor” at this time. As the best ballet company in the world, the National Academic Theatre of Ballet in Minsk won the Benois de la Dance Prize in 1996.

Although the Belarusian government has made an effort to promote more traditional Belarusian music on the radio and limit the amount of foreign music played, rock music has grown in popularity in recent years. Belarus has been sending performers to the Eurovision Song Contest since 2004.

In 1887, Marc Chagall was born in Liozna, close to Vitebsk. He lived in Soviet Belarus during the First World War, when he rose to prominence as one of the nation’s most renowned painters, belonged to the modernist avant-garde, and founded the Vitebsk Arts College.

Dress

The Kievan Rus’ era is when traditional Belarusian clothing first appeared. Because of the chilly weather, clothing was constructed primarily of wool or flax to retain body heat. Polish, Lithuanian, Latvian, Russian, and other European civilizations were among those whose intricate designs adorned them. Different design patterns have evolved in each area of Belarus. A popular motif seen in traditional attire presently adorns the hoist of the Belarusian national flag, which was chosen following a contentious vote in 1995.

Cuisine

The staple foods of Belarusian cuisine include bread, meat (especially pork), and vegetables. Typically, food is stewed or cooked slowly. Belarusians typically have two substantial meals later in the day after a small breakfast. In Belarus, rye bread is more common than wheat bread since the growing environment is not conducive to wheat production. When receiving a guest or visitor, a host customarily offers an offering of bread and salt as a sign of hospitality.