The West Asian island nation of Bahrain is formally known as the Kingdom of Bahrain. Located on the Persian Gulf, the small archipelago is composed of 33 manmade islands and 50 natural islands, with Bahrain Island constituting the majority of the country’s area. Bahrain is located between Qatar and Saudi Arabia’s northeastern shore, with the King Fahd Causeway connecting the two.

According to elaborations of UN data, as of May 14, 2023, Bahrain had a population of 1,501,635 people, of which 712,362 were citizens of Bahrain. After the Maldives and Singapore, Bahrain is the third-smallest country in Asia, covering an area of around 760 square kilometers (290 sq mi). Manama is the biggest and capital city.

Archaeologist Geoffrey Bibby claims that the ancient Dilmun civilization was located in Bahrain. Since ancient times, it has been well-known for its pearl fishery, which up until the 19th century was regarded as the greatest in the world. During the time of Muhammad, in 628 AD, Bahrain was among the first regions to be affected by Islam. Bahrain was governed by the Portuguese Empire from 1521 to 1602 when Shah Abbas the Great of Safavid Iran drove them out.

This followed a period of Arab dominance. Bahrain was taken from Nasr Al-Madhkur by the Bani Utbah and their allies in 1783, and the Al Khalifa royal family has controlled it ever since. Ahmed al Fateh was Bahrain’s first hakim.

After many treaties with the British, Bahrain became a protectorate of the United Kingdom in the late 1800s. It proclaimed its independence in 1971. After being reduced from an emirate to a semi-constitutional monarchy in 2002, Bahrain’s new constitution, which established Sharia as the primary source of law, included Article 2.

After decades of investment in the banking and tourist industries, Bahrain established the first post-oil economy in the Persian Gulf; as a result, several of the biggest financial institutions in the world have operations in the nation’s capital. The World Bank classifies it as a high-income economy.

Bahrain is a part of the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, the Arab League, the Non-Aligned Movement, and the United Nations. Bahrain is a Shanghai Cooperation Organization Dialogue partner.

Meaning and Origin

“The two seas” is the original meaning of al-Bahrayn, which is derived from the Arabic term Bahr, which means “sea” in Bahrain. The name, however, does not adhere to the grammatical norms for duals since it has been lexicalized as a feminine proper noun and is therefore always Bahrayn and never Bahrān, the anticipated nominative form.

As in the case of the demonym Bahraynī or the national song Bahraynunā (“our Bahrain”), endings are appended to words without altering their meaning. In response, the more strictly accurate phrase Bahrī (lit. “belonging to the sea”) was not employed because it would have been misinterpreted, according to the medieval grammarian al-Jawahari.

Which of the “two seas” the name Bahrayn originally referred to is still up for debate. The phrase is used five times in the Quran, however, it does not allude to the contemporary island that the Arabs initially called Awal.

Presently, the bays to the east and west of Bahrain, the seas to the north and south of the island, or the fresh and salt water found above and below the surface are often understood to constitute the “two seas” of Bahrain.

Apart from wells, tourists have been observing freshwater springs emerging in the middle of seawater in certain parts of the sea north of Bahrain since ancient times. The al-Ahsa area offers an alternate explanation for Bahrain’s toponymy: the two seas were a calm lake on the Arabian mainland and the Great Green Ocean, or the Persian Gulf.

“Bahrain” refers to the Eastern Arabian area comprising Southern Iraq, Kuwait, Al-Hasa, Qatif, and Bahrain until the late Middle Ages. The area extended from the Strait of Hormuz in Oman to Basra in Iraq. Iqlīm al-Bahrayn called this his “Bahrayn Province.”

It’s unclear exactly when the Awal archipelago was the only place the name “Bahrain” was used to refer to. For millennia, the whole Eastern Arabian coast was referred to as “Bahrain”. Up to the 1950s, the name of the island and kingdom was also frequently spelled Bahrein.

Past Events

In the past

Dilmun, a significant Bronze Age trading hub between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley, was located in Bahrain. Later, the Babylonians and Assyrians reigned over Bahrain.

Bahrain was a member of the Achaemenid Empire from the sixth and the third century BC. Around 250 BC, Parthia conquered the Persian Gulf and expanded its sphere of influence to include Oman. To control trade routes, the Parthians erected garrisons along the Persian Gulf’s southern shore.

When Alexander the Great’s Greek admiral Nearchus landed in Bahrain during the classical era, the Greeks referred to the island as Tylos, the hub of the pearl trade. The first of Alexander’s commanders to visit the island is thought to have been Nearchus, who reported: “That on the island of Tylos, situated in the Persian Gulf, are large plantations of cotton trees, from which are manufactured clothes called sindones, of strongly differing degrees of value, some being costly, others less expensive.” Nearchus discovered a lush region that was a part of a vast trading network. These are used not just in Arabia but also in India.”

According to the Greek historian Theophrastus, walking canes decorated with symbols that were traditionally carried in Babylon were a popular export from Bahrain, which was largely covered in these cotton trees.

Though it’s unclear if Alexander’s plans for Greek colonist settlement in Bahrain were carried out to the extent he intended, Bahrain became deeply integrated into the Hellenized world, with Greek serving as the official language of the higher classes and Aramaic being used on a daily basis. Zeus is depicted sitting on local coins; it’s possible that he was revered there as a syncretized version of the Arabian sun deity Shams. Greek sports events were also held at Tylos.

Bahrain was the original home of the Phoenicians, according to Greek historian Strabo. Herodotus also thought that Bahrain was the Phoenicians’ homeland. Arnold Heeren, a 19th-century German classicist, endorsed this theory when he stated: “In the Greek geographers, for instance, we read of two islands, named Tyrus or Tylos, and Aradus, which boasted that they were the mother country of the Phoenicians, and exhibited relics of Phoenician temples.”

The closeness between the terms “Tylos” and “Tyre” has drawn attention, as the residents of Tyre, in particular, have long believed that they are of Persian Gulf descent. Nonetheless, there is scant proof of any human habitation in Bahrain at the purported period of this migration.

According to some theories, the Semitic Tilmun (from Dilmun) became Tylos. Up until Ptolemy’s Geographia, the islands were referred to as Tylos, however, the locals are called Thilouanoi. A few place names in Bahrain date back to the Tylos period. For example, Arad, a residential neighborhood of Muharraq, is said to have sprung from the ancient Greek name for Muharraq, “Arados”.

The first Sassanid dynasty emperor, Ardashir I, invaded Oman and Bahrain in the third century and overthrew Sanatruq, the Bahraini monarch.

An additional god worshipped in Bahrain was an ox named Awal (Arabic: اوال). In Muharraq, worshippers erected a sizable statue of Awal, which is sadly gone today. Awal was the name given to Bahrain many centuries after Tylos.

Bahrain developed into a major hub for Nestorian Christianity by the fifth century, with the hamlet of Samahij serving as the seat of bishops. The synodal records of the Oriental Syriac Church state that a bishop by the name of Batai was excommunicated from the Bahraini church in 410.

The Byzantine Empire frequently punished the Nestorians as heretics, although Bahrain was free from its rule and provided some protection. Bahrain’s Christian heritage is reflected in the names of a number of Muharraq villages today; Al Dair translates to “the monastery”.

Christian Arabs (mostly Abd al-Qays), Persians (Zoroastrians), Jews, and Aramaic-speaking agriculturalists made up Bahrain’s pre-Islamic population. The Arabized “descendants of converts from the original population of Christians (Aramaeans), Jews, and Persians inhabiting the island and cultivated coastal provinces of Eastern Arabia at the time of the Muslim conquest,” according to Robert Bertram Serjeant, might be the Baharna. Pre-Islamic Bahrain’s sedentary population spoke Syriac as a liturgical language and Aramaic and, to a lesser extent, Persian.

The advent of Islam

Muhammad’s Al Kudr Invasion was his first encounter with the Bahraini people. Muhammad gave the command to strike the Banu Salim tribe unexpectedly because they were preparing an attack on Medina. The tribesmen withdrew when they discovered Muhammad was heading an army to fight with them, despite the fact that he had received reports that certain tribes were raising an army in Bahrain and were ready to assault the mainland.

According to conventional Islamic narratives, in AD 628, Muhammad dispatched Al-Ala’a Al-Hadrami as an ambassador to the Bahrain peninsula as part of Zayd ibn Harithah (Hisma). The local monarch, Munzir ibn Sawa Al Tamimi, accepted his mission and converted the whole province.

Middle Ages

The millenarian Ismaili Muslim group known as the Qarmatians took over Bahrain in 899 with the goal of establishing an ideal society founded on reason and property transfer among initiates. The Qarmatians then seized Mecca in 930 and took the holy Black Stone back to their headquarters in Ahsa, in medieval Bahrain, in exchange for a ransom.

They also demanded payment from the caliph in Baghdad. Historian Al-Juwayni claims that the stone was returned in 951—22 years later—under unexplained circumstances. It was tossed into the Great Mosque of Kufa in Iraq, wrapped in a sack, along with a message that said, “By command we took it, and by command, we have brought it back.” The Black Stone broke into seven pieces as a result of being stolen and removed.

The Qarmatians were deposed by the Arab Uyunid dynasty of al-Hasa, who ruled over the whole Bahrain peninsula in 1076 after they were defeated by the Abbasids in 976. Bahrain was ruled by the Uyunids until 1235 when the Persian king of Fars temporarily took control of the archipelago.

After overthrowing the Uyunid dynasty in 1253, the Bedouin Usfurids took control of eastern Arabia, which included the Bahraini islands. Although the Shi’ite Jarwanid dynasty of Qatif ruled the islands locally, the archipelago became a subject state of the Kings of Hormuz in 1330. Midway through the 15th century, the Jabrids—a Bedouin dynasty that dominated most of eastern Arabia out of Al-Ahsa—took control of the archipelago.

Portuguese and early modern era

The Portuguese Empire took control of Bahrain in 1521 by forming an alliance with Hormuz, overthrowing the Jabrid monarch Muqrin ibn Zamil, who was assassinated in the process. For around 80 years, Sunni Persian rulers were the primary source of Portuguese authority. Shia Islam gained momentum when Abbas I of Safavid Iran drove the Portuguese from the islands in 1602.

Persians ruled the archipelago for the following two centuries, with the Ibadis of Oman’s invasions in 1717 and 1738 interfering. For the most part of this time, they used Bushehr as a conduit for government or immigrant Sunni Arab clans as a means of indirectly controlling Bahrain.

The latter were known as Huwala tribesmen, who were returning from Persian lands in the north to the Arabian side of the Persian Gulf. On behalf of Iranian Zand chieftain Karim Khan Zand, the Huwala tribe of Nasr Al-Madhkur invaded Bahrain in 1753 and reinstated direct Iranian sovereignty.

Following his loss in the Battle of Zubarah in 1782 by the Bani Utbah clan and their allies, Al-Madhkur lost the islands of Bahrain in 1783. The Bani Utbah were not strangers to Bahrain; they had lived there since the seventeenth century.

They began buying date palm plantations in Bahrain around that period; according to a record, one of the sheiks of the Al Bin Ali tribe, a branch of the Bani Utbah, had purchased a palm estate from Mariam bint Ahmed Al Sanadi in Sitra island 81 years before to the arrival of the Al Khalifa.

Originally the Bani Utbah’s center of power, Zubarah in the Qatar peninsula was ruled by the Al Bin Ali, a dominant tribe. As a self-governing tribe, the Al Bin Ali enjoyed an essentially autonomous position in Bahrain following the Bani Utbah’s takeover. In Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the Eastern Province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, they flew a banner known as the Al-Sulami flag, which has three white and four crimson stripes.

After Nasr Al-Madhkur of Bushehr fell, some Arab family clans and tribes from Qatar later relocated to Bahrain. Al-Kuwari, Al-Mannai, Al-Noaimi, Al-Rumaihi, Al-Sulaiti, Al-Sadah, Al-Thawadi, and other families and tribes were among these families, which also included the House of Khalifa.

In 1799, the House of Khalifa relocated to Bahrain from Qatar. Due to their predatory tendencies of preying on caravans in Basra and commercial ships in the Shatt al-Arab canal, their forefathers were first driven out of Umm Qasr in central Arabia by the Ottomans. In 1716, the Turks drove them out of Kuwait, where they stayed until 1766.

Al Sabah became the only owner of Kuwait when the Utub Federation’s Al Jalahma and House of Khalifa moved to Zubarah in present-day Qatar in the 1760s.

19th century and later

Both the Omanis and the Al Sauds attacked Bahrain at the beginning of the 1800s. It was ruled by a twelve-year-old when Sayyid Sultan of Oman appointed his son Salim as governor of the Arad Fort in 1802.

The Sheikh of Bahrain wrote to William Bruce, a British politician living in the Persian Gulf, in 1816, expressing anxiety over a rumor that Britain might back the Imam of Muscat’s invasion of the island. He made an unofficial arrangement promising the Sheikh that Britain would continue to be a neutral party and sailed to Bahrain to reassure him that this was not the case.

Following the signing of a treaty partnership, the Al Khalifa tribe was acknowledged by the United Kingdom in 1820 as the rulers of Bahrain, or “Al-Hakim” in Arabic. They sought protection from the British and Persians, but ten years later they still had to pay annual payments to Egypt.

The Al Khalifas employed the same strategy in 1860 to thwart British attempts to oust Bahrain. By writing letters to the Ottomans and Persians, Al Khalifas consented to hand up Bahrain to them in March as they were able to provide better terms. Bahrain was ultimately subjugated by the Government of British India when the Persians declined to defend it. Colonel Pelly put Bahrain under British protection and control when he signed a new treaty with Al Khalifas.

Another agreement was inked by British agents with the Al Khalifas after the 1868 Qatari-Bahraini War. It said that the ruler could not transfer any of his lands to any other country save the United Kingdom and could not establish diplomatic ties with any other country without the approval of the British government.

In exchange, the British pledged to defend Bahrain from any maritime aggression and to provide assistance in the event of a land invasion. More significantly, the British pledged to uphold the Al Khalifa’s precarious position as the nation’s rulers by guaranteeing their assistance. The British were granted Bahrain’s protectorate status through further agreements made in 1880 and 1892.

Bahrain’s population started to become unrest after Britain formally took total control of the region in 1892. The first and largest rebellion against Bahrain’s monarch at the time, Sheikh Issa bin Ali, occurred in March 1895. The first Al Khalifa to reign without ties to Persia was Sheikh Issa. At this time, Sir Arnold Wilson, the author of The Persian Gulf and Britain’s envoy in the Persian Gulf, arrived in Bahrain from Muscat. As the rebellion gained momentum, numerous demonstrators were slain by British soldiers.

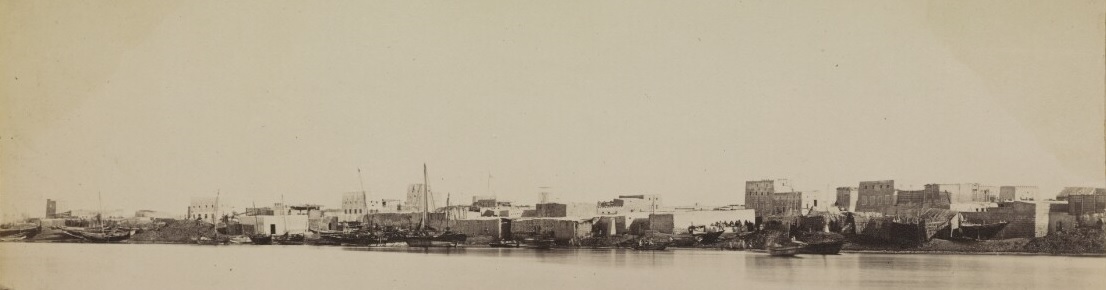

The island was mostly used for pearl fishing before the petroleum business took off, and even in the 19th century, it was thought to have the best pearl fishery in the world. The ancient Qaṣr es-Sheikh was among the historical places that German explorer Hermann Burchardt photographed during his 1903 journey to Bahrain. These images are currently housed at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin. There were over 400 ships seeking pearls before World War I, with an annual export of more than £30,000.

A group of Bahraini businessmen called for limitations on British power in their nation in 1911. The leaders of the gang were then taken into custody and banished to India. In 1923, Sheikh Issa bin Ali was succeeded by his son, and administrative changes were implemented by the British.

A few families and opponents of the clergy, including Al Dosari, were sent to Saudi Arabia or departed. Charles Belgrave, who served as the ruler’s advisor until 1957, assumed de facto control of the nation three years after the British placed them in that position.

Belgrave instituted several changes, including the first modern school to be established in the nation in 1919 and the abolition of slavery in 1937. Concurrently, the pearl diving sector saw exponential growth.

Rezā Shāh, the Iranian Shah at the time, requested Bahrain’s sovereignty in a letter to the League of Nations in 1927. Belgrave responded by enacting severe measures, such as inciting confrontations between Sunni and Shia Muslims in an effort to quell the protests and curtail Iranian influence.

Belgrave went so far as to propose renaming the Persian Gulf the “Arabian Gulf,” but the British government rejected his idea. Concerns over Saudi and Iranian aspirations in the area drove Britain’s interest in Bahrain’s growth.

Oil was discovered in 1932 by the Bahrain Petroleum Company (Bapco), a division of the Standard Oil Company of California (Socal).

The Bahrain Airport was built in the early 1930s. There were Handley Page HP42 aircraft used by Imperial Airways. The Bahrain Maritime Airport was built later that decade specifically for seaplanes and flying boats.

Bahrain joined the Allies on September 10, 1939, and took part in the Second World War. Four Italian SM.82 bombers attacked Allied-run oil facilities in Bahrain and the Saudi Arabian oilfields at Dhahran on October 19, 1940. The attack pushed the Allies to strengthen Bahrain’s defenses, even though it only did little damage in both places. This further taxed their military resources.

Rising anti-British sentiment following World War II caused riots in Bahrain and other Arab countries. The Jewish community was the target of the rioting. The majority of Bahrain’s Jewish population fled their homes and fled to Bombay in 1948 as a result of escalating conflicts and theft.

They eventually settled in Israel (Pardes Hanna-Karkur) and the United Kingdom. There were 37 Jews left in the nation as of 2008. The National Union Committee was established in the 1950s by reformists in response to sectarian conflicts.

They called for the overthrow of Belgrave, the creation of an elected public assembly, and a series of demonstrations and nationwide strikes. A month-long insurrection occurred in 1965 as a result of the hundreds of Bahrain Petroleum Company employees being put off.

Independence

Even though the Shah of Iran was claiming historical authority over Bahrain on August 15, 1971, he approved a UN-conducted referendum, leading to Bahrain’s final declaration of independence and the signing of a new friendship treaty with the United Kingdom. Later in the year, Bahrain became a member of the Arab League and the United Nations.

Bahrain gained a lot from the oil boom of the 1970s, but the economy suffered from the ensuing collapse. When Bahrain took the position of Beirut as the financial center of the Middle East after the war drove Lebanon’s sizable banking industry out of the nation, the nation had already started to diversify its economy and profited even more from the Lebanese Civil War in the 1970s and 1980s.

Under the aegis of a front group called the Islamic Front for the Liberation of Bahrain, the Bahraini Shia community staged a botched coup attempt in 1981 in response to the Islamic revolution that took place in Iran in 1979. The coup aimed to establish Hujjatu l-Islām Hādī al-Mudarrisī, a Shia cleric who was exiled to Iran, as the supreme leader of a theocratic country. A gang of young people attacked female runners who were running an international marathon bare-legged in December 1994 with stones. The ensuing altercation with the police quickly turned into civil unrest.

Between 1994 to 2000, there was a public revolt in which Islamists, liberals, and leftists banded together. About forty people died as a result of the incident, which came to an end in 1999 when Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa was crowned Bahrain’s emir.

He established parliamentary elections, granted suffrage to women, and freed all political prisoners. A referendum held on February 14–15, 2001, yielded overwhelming approval for the National Action Charter.

Bahrain officially changed its name from the State (dawla) of Bahrain to the Kingdom of Bahrain on February 14, 2002, in conjunction with the approval of the National Action Charter. Simultaneously, Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa became King instead of Emir as the Head of State.

In October 2001, following the September 11 attacks, the nation took part in military operations against the Taliban by deploying a frigate for humanitarian relief and rescue missions in the Arabian Sea. Consequently, the administration of US President George W.

Bush named Bahrain a “major non-NATO ally” in November of that same year. Bahrain had given Saddam Hussein shelter in the days preceding the assault and was against the invasion of Iraq. After the International Court of Justice in The Hague settled the boundary dispute over the Hawar Islands in 2001, relations with neighboring Qatar improved. In 2004, Bahrain and the United States established a free trade deal after the country’s political liberalization.

The fort and archaeological complex known as Qal’at al-Bahrain was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2005.

2011 Bahraini protests

Early in 2011, Bahrain’s Shia majority began massive protests against its Sunni government, sparked by the Arab Spring in the area. After the government raided demonstrators tented in Pearl Roundabout before daybreak, protests were first permitted.

A month later, it proclaimed a three-month state of emergency and asked Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Cooperation Council nations for security help. Following that, the government began to crack down on the opposition, making thousands of arrests and torturing people on a regular basis.

Dozens of protestors and security personnel lost their lives in near-daily altercations. There were continuous protests, occasionally organized by opposing groups. As of March 2014, over 80 citizens and 13 police officers had perished.

Physicians for Human Rights claims that 34 of these fatalities were caused by the government’s use of tear gas that was first produced by Federal Laboratories, a U.S.-based company. Several debates have been triggered by the Arab media’s lack of coverage of the Persian Gulf revolt in comparison to other Arab Spring protests. The United States and other parties claim that Iran is involved in the armament of extremists in Bahrain.

Post-Arab Spring years

The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia provided military support to the Saudi-led intervention in Bahrain, which resulted in the rapid repression of large protests against the government.

Inspired by the Arab Spring, the 2011 Bahraini revolt resulted in a brutal crackdown on the mostly Shiite protestors who sought an elected government, putting the Sunni monarchy’s hold on power in jeopardy.

Three oyster beds make up the Bahrain Pearling Trail, which was inscribed as “Pearling, Testimony of an Island Economy” when it was named a World Heritage Site in 2012.

Bahrain established a committee on April 9, 2020, to compensate private sector workers for a three-month duration in an effort to alleviate the financial strain brought on by the COVID-19 epidemic.

International condemnation was swift when Bahrain denounced the movement as an Iranian conspiracy, outlawed opposition groups, tried citizens in military courts, and imprisoned several nonviolent political opponents.

“Ten years after Bahrain’s popular uprising, systemic injustice has intensified and political repression targeting dissidents, human rights defenders, clerics, and independent civil society have effectively shut any space for the peaceful exercise of the right to freedom of expression or peaceful activism”, Amnesty International said in a statement.

Bahrain is still financially and militarily dependent on Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, however, this is beginning to change as a result of the government’s economic reforms.

Geographical

Bahrain is an archipelago in the Persian Gulf that is primarily flat and dry. The region is composed of a flat desert plain that gradually rises to a low central escarpment, with the 134-meter (440-foot) Mountain of Smoke (Jabal ad Dukhan) serving as its highest point. Due to land reclamation, Bahrain’s overall area expanded from 665 km2 (257 sq mi) to 780 km2 (300 sq mi), making it slightly bigger than Anglesey.

Frequently referred to as an archipelago consisting of 33 islands, significant land reclamation initiatives have resulted in an increase in the number of islands and island groupings to 84 by August 2008. Bahrain has a 161-kilometer (100-mile) coastline but no shared land borders with any other nation.

An additional 22 km (12 nmi) of territorial sea and 44 km (24 nmi) of contiguous zone are also claimed by the nation. Bahrain Island, the Hawar Islands, Muharraq Island, Umm a Nasan, and Sitra are the five major islands in Bahrain.

Bahrain experiences scorching, muggy summers and moderate winters. Large amounts of natural gas and oil, as well as fish in the offshore waters, are the nation’s natural resources. The area that is arable only makes up 2.82% of the total.

The major natural risks for Bahrainis are the sporadic dust storms and droughts that affect around 92% of the country. Bahrain faces a number of environmental problems, such as desertification from the loss of its limited amount of arable land, coastal degradation from oil spills and other discharges from big tankers, oil refineries, distribution centers, and illegal land reclamation at locations like Tubli Bay, which damages coastlines, coral reefs, and marine vegetation.

The main aquifer in Bahrain, the Dammam Aquifer, has been overused by the household and agricultural sectors, which has caused neighboring brackish and salty water bodies to saline it. The sources of aquifer salinization were located and their spheres of effect were defined by a hydrochemical analysis.

According to the analysis, groundwater from Bahrain’s northwest, where the aquifer gets its water from lateral underflow from eastern Saudi Arabia, moves toward the country’s south and southeast, considerably altering the aquifer’s water quality. The aquifer is becoming salinized in four different ways: the underlying brackish-water zones in the eastern, western, and north-central regions are causing brackish-water up-flow; the eastern region is experiencing seawater intrusion; the southwestern region is experiencing sabkha water intrusion; and a small area in the western region is experiencing irrigation return flow.

Climate

The water authorities in Bahrain have four options for managing the quality of groundwater; these are examined, and priority regions are suggested depending on the kind and quantity of each source of salinization as well as the groundwater usage in that area.

Summertime brings intense heat. Because of the shallow oceans around Bahrain, summertime temperatures rise rapidly, resulting in extremely high humidity, particularly at night. In the correct circumstances, summer temperatures can rise as high as 40 °C (104 °F). Bahrain receives very little and erratic rainfall. The majority of the year’s precipitation falls during the winter, with an average of 70.8 millimeters, or 2.8 inches, falling. In April 2024, the nation was hit by extensive floods as a result of the Gulf region’s significant rains.

Biodiversity

The Bahraini archipelago is home to around 330 different species of birds, 26 of which breed there. During the winter and fall, millions of migrating birds travel across the Persian Gulf region. Chlamydotis undulata, one species that is internationally threatened, often migrates in the fall.

Bahrain’s numerous islands and shallow waters play a significant role in the worldwide Socotra cormorant breeding population; over the Hawar Islands, records show that up to 100,000 pairs of these birds have been observed. The Arabian oryx is the national animal of Bahrain, while the bulbul is the national bird. And Bahrain’s national flower is the much-loved Deena.

The Bahraini archipelago is home to around 330 different species of birds, 26 of which breed there. During the winter and fall, millions of migrating birds travel across the Persian Gulf region. Chlamydotis undulata, one species that is internationally threatened, often migrates in the fall.

Bahrain’s numerous islands and shallow waters play a significant role in the worldwide Socotra cormorant breeding population; over the Hawar Islands, records show that up to 100,000 pairs of these birds have been observed. The Arabian oryx is the national animal of Bahrain, while the bulbul is the national bird. And Bahrain’s national flower is the much-loved Deena.

Bahrain is home to just eighteen species of mammals; hedgehogs, gazelles, and desert rabbits are all widespread in the wild, but the Arabian oryx was driven to extinction there due to hunting. Along with 21 species of butterflies and 307 species of vegetation, 25 species of amphibians and reptiles were identified.

The marine biotopes are varied and comprise large mudflats and seagrass beds, sporadic coral reefs, and offshore islands. For several endangered species, like dugongs and green turtles, seagrass beds are crucial feeding areas. Bahrain outlawed the taking of dolphins, sea cows, and marine turtles inside its territorial seas in 2003.

The Hawar Islands Protected Area is a globally recognized destination for bird migration, offering a variety of migratory seabirds significant nesting and feeding grounds. The second-biggest dugong aggregation in the world, after Australia, is made up of foraging dugongs from the Hawar Islands, which are home to the world’s largest breeding colony of Socotra cormorants.

Four of Bahrain’s five officially declared protected areas are found in maritime settings. They are as follows:

- Islands of Hawar

- Off the coast of Bahrain is Mashtan Island.

- Bay of Arad, Muharraq.

- Bay of Tubli

- The sole protected area on land that is also the only one that is regularly administered is Al Areen Wildlife Park, a zoo and breeding facility for endangered animals.

Compared to other nations, Bahrain emits a lot of carbon dioxide per person, mostly because it is a small nation.