Armenia, also known as the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked nation in West Asia’s Armenian Highlands (/ˑːrˈmiːniə/ ar-MEE-nee-ə). It is surrounded by Iran and the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan to the south, Georgia to the north, Azerbaijan to the east, and Turkey to the west. It is a part of the Caucasus region. The largest city, financial hub, and capital is Yerevan.

Armenia is a democratic nation-state that is unitary and multiparty, with a rich cultural legacy. The Hayasa-Azzi, Shupria, and Nairi have historically lived in the Armenian Highlands. An ancient dialect of the Indo-European language Proto-Armenian had spread to the Armenian Highlands by at least 600 BC.

In 860 BC, Urartu became the first Armenian kingdom; by the 6th century BC, the Satrapy of Armenia had taken its place. Under Tigranes the Great, the Kingdom of Armenia peaked in the first century BC, and in 301 it became the first state in history to declare Christianity to be its official religion. The oldest national church in the world, the Armenian Apostolic Church, is still acknowledged as the main religious institution in Armenia.

Around the beginning of the fifth century, the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires divided the old Armenian country. The Bagratid Kingdom of Armenia was reestablished in the ninth century and fell under the Bagratuni dynasty in 1045. Between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries, an Armenian principality called Cilician Armenia—which eventually became a kingdom—was situated on the Mediterranean coast.

The Ottoman and Persian empires, which alternated in power over the ages, reigned over the ancient Armenian homeland, which is made up of Eastern Armenia and Western Armenia, during the 16th and 19th centuries. The majority of the western regions of the ancient Armenian homeland were still ruled by the Ottoman Empire by the 19th century, while Eastern Armenia had been taken over by the Russian Empire. Up to 1.5 million Armenians who were residing in the Ottoman Empire on their ancestral lands were methodically wiped off during the Armenian genocide that took place during World War I.

Following the Russian Revolution, the Russian Empire collapsed in 1918, and all non-Russian nations proclaimed their independence, resulting in the founding of the First Republic of Armenia. The state became the Armenian SSR when it joined the Soviet Union in 1920. The breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 led to the independence of the current Republic of Armenia.

According to the Human Development Index (2021), Armenia is a developing nation that is ranked 85th. Mineral extraction and industrial output are the main pillars of its economy. Armenia is seen as geopolitically European even though it is physically located in the South Caucasus.

As a result of its geopolitical alignment with Europe, Armenia is a member of many European organizations, such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Council of Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe, the Eastern Partnership, and Eurocontrol. In addition, Armenia belongs to a number of regional organizations that span all of Eurasia, such as the Eurasian Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the Collective Security Treaty Organization, and the Eurasian Economic Union.

Up until its collapse in September 2023, Armenia backed the de facto autonomous Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh), which was established in 1991 on land that is internationally recognized as being a part of Azerbaijan.

Etymology

ֵ̀֡τ (Hayk) was the nation’s original native Armenian name, albeit it is hardly used now. During the Middle Ages, the Persian suffix -stan (place) was added to the modern name π֡صءؽؿס (Hayastan), which gained popularity. But the word Hayastan has far older roots; it was first mentioned in writings by Agathangelos, Faustus of Byzantium, Ghazar Parpetsi, Koryun, and Sebeos in the fifth century.

The name has historically come from Hayk (πֵ֡֯), the great-great-grandson of Noah and the mythical patriarch of the Armenian people. According to the author Moses of Chorene (Movsis Khorenatsi), who lived in the Ararat region in the fifth century AD, Hayk defeated the Babylonian king Bel in 2492 BC. It’s unclear where the name came from in the past. Additional speculation is that the name Hay originates from one of the two Hittite vassal nations that were confederated, the Ḫayaša-Azzi (1600–1200 BC).

The Old Persian Behistun Inscription (515 BC) mentions the exonym Armenia under the name Armina (𐎠). Hecataeus of Miletus (c. 550–476 BC) is the first person to cite the Ancient Greek names Ἀρμενία (Armenía) and Ἀρμένιoι (Arménioi, “Armenians”). Many facets of Armenian village life and hospitality are described by Xenophon, a Greek general who participated in various Persian expeditions, in 401 BC.

Certain academics have associated the name Armenia with either the Late Bronze Age state of Arme (Shupria) or the Early Bronze Age state of Armani (Armanum, Armi). Since the languages used in these kingdoms are unknown, these links are ambiguous. The location of the ancient Armani site is also up for discussion, even though it is generally acknowledged that Arme was situated just west of Lake Van (likely in the Sason area and hence in the larger Armenia region).

According to some contemporary academics, it was inhabited, at least in part, by an early Indo-European-speaking population and has been located close to modern-day Samsat. It’s probable that Armini, which means “inhabitant of Arme” or “Armean country” in Urartian, is where the term Armenia first appeared.

The Urumu, who launched an invasion of Assyria from the north in the 12th century BC with the help of the Mushki and the Kaskians, may have been the Arme tribe mentioned in Urartian writings. The Urumu are said to have established themselves around Sason, giving names to the Arme districts as well as the adjacent territories of Urme and Inner Urumu.

Since this was an exonym, it could have meant “thick forest, wasteland”; see also armāniš (tree), armaḫḫu (thick forests, thicket), and armutu (wasteland). The woodlands in the north were thought to be home to terrible creatures by those from the south.

Armenia comes from the name of Aram, a lineal descendant of Hayk, according to the chronicles of both Moses of Chorene and Michael Chamchian. The Book of Jubilees confirms that Aram is the son of Shem, as indicated by the Table of Nations in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament.

The fourth component emerged for Aram, which included the all of Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the Chaldee Mountains, the country of 'Arara,' and the boundary between them.

The Ararat Mountains are again attributed to Shem in Jubilees 8:21; however, Jubilees 9:5 elaborates that Aram is to be given the Mountains.

In his Antiquities of the Jews, the historian Flavius Josephus adduces,

Out of the four sons of Aram, Uz created Trachonitis and Damascus; this territory is situated between Palestine and Celesyria. Aram had the Aramites, who the Greeks named Syrians. Currently known as Charax Spasini, Ul created Armenia, together with Gather the Bactrians and Mesa the Mesaneans.

Past Events

Ancient

The discovery of Acheulean artifacts, which are typically found near obsidian outcrops that date back more than a million years, supports the existence of the first human traces.

The Nor Geghi 1 Stone Age site in the Hrazdan River Valley is home to the most recent and significant excavation. Ancient artifacts dating back thousands of years might suggest that this phase of human technical advancement spread sporadically over the Old World instead of coming from a single source, as was traditionally believed to be Africa.

Armenia was the site of several early Bronze Age villages, including those in the Valley of Ararat, Shengavit, Harich, Karaz, Amiranisgora, Margahovit, and Garni. Shengavit Settlement, which was situated on the current site of Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, is one of the significant Early Bronze Age sites.

Things of this sort, such as the earliest shoe, wagon, skirt, and wine-making facilities, have been found in Armenia.

In the past

Armenia is located in the hills around the Ararat Mountains. Around 4000 BC, there is evidence of an early civilization in Armenia that existed during the Bronze Age and beyond. Findings from 2010 and 2011 archeological surveys at the Areni-1 cave complex include the world’s oldest known leather shoe, skirt, and wine-making facilities.

Greater Armenia was home to a number of Bronze Age empires and civilizations, including the Trialeti-Vanadzor culture, Hayasa-Azzi, and Mitanni (in southwest historical Armenia), all of which are thought to have been populated by Indo-Europeans.

The Armenian Highlands were first claimed by the Nairi Confederation and then by Urartu, its successor. The ethnogenesis of the Armenians involved all of the above-named countries and confederacies. A sizable cuneiform lapidary inscription discovered in Yerevan proved that King Argishti I constructed the present-day capital of Armenia during the summer of 782 BC. One of the oldest cities in the world to still be inhabited is Yerevan.

The Armenian Highlands were ruled by the Medes for a while when the kingdom of Urartu fell at the start of the sixth century BC, and then they became a part of the Achaemenid Empire. From the latter part of the 6th century BC until the latter part of the 4th century BC, Armenia belonged to the Achaemenid kingdom, which was divided into two satrapies: XIII (the western portion, with the capital at Melitene) and XVIII (the northern part).

The first geographical region that neighboring populations referred to as Armenia was founded in the Achaemenid Empire’s domains around the late 6th century BC under the Orontid Dynasty.

Under King Artaxias I, the kingdom gained complete independence from the Seleucid Empire’s sphere of influence in 190 BC, ushering in the Artaxiad dynasty. Under Tigranes the Great, Armenia rose to prominence between 95 and 66 BC, becoming the most powerful kingdom east of the Roman Republic.

During the rule of Tiridates I, the founder of the Armenian Arsacid dynasty, which was a subset of the Parthian Empire, Armenia was under the influence of the Persian Empire throughout the following centuries. The kingdom of Armenia experienced both periods of independence and autonomy under modern empires throughout its history.

Due to its advantageous location between two continents, it has been invaded by numerous peoples, such as Assyria (under Ashurbanipal, whose borders stretched as far as Armenia and the Caucasus Mountains between 669 and 627 BC), the Medes, the Achaemenid Empire, the Greeks, Parthians, Romans, Sasanian Empire, Byzantine Empire, Arabs, the Seljuk Empire, the Mongols, the Ottoman Empire, the Iranian dynasties Safavid, Afsharid, and Qajar, and the Russians.

Ancient Armenian religion was historically associated with a system of ideas that gave rise to Zoroastrianism in Persia. In addition to a pantheon of gods that included Aramazd, Vahagn, Anahit, and Astghik, it placed special emphasis on the worship of Mithra. The nation followed the twelve-month solar Armenian calendar.

Early in the fourth century AD, Christianity made its way throughout the nation. Ten years before the Roman Empire officially tolerated Christianity under Galerius and thirty-six years before Constantine the Great was baptized, Tiridates III of Armenia (238–314) established Christianity as the state religion in 301, ostensibly in defiance of the Sasanian Empire. This made Tiridates III of Armenia the first officially recognized Christian state. Armenia was mostly a Zoroastrian nation before this, in the later half of the Parthian era.

A marzpanate of the Sasanian Empire, much of Armenia was included after the Kingdom of Armenia fell in 428. Armenia acquired autonomy and Christian Armenians were able to continue practicing their religion after the Battle of Avarayr in 451.

Middle Ages

After the Rashidun Caliphate overthrew the Sassanid Empire in the middle of the 7th century and brought back the Armenian territories that the Byzantine Empire had stolen, Armenia became Arminiya, an independent principality under the Umayyad Caliphate.

The Caliph and the Byzantine Emperor acknowledged the Prince of Armenia as the principality’s ruler. It belonged to the Arab-created administrative division/emirate Arminiya, which was centered in the Armenian city of Dvin and comprised portions of Georgia and Caucasian Albania. Arminiya persisted until 884 when Ashot I of Armenia’s crumbling Abbasid Caliphate granted it back freedom.

Up until 1045, the Bagratuni dynasty controlled the resurgent Armenian kingdom. While acknowledging the supremacy of the Bagratid kings, several regions of the Bagratid Armenia eventually broke away to become independent kingdoms and principalities. These included the Kingdom of Syunik in the east, the Kingdom of Artsakh on the area that is now modern-day Nagorno-Karabakh, and the Kingdom of Vaspurakan, which was ruled by the House of Artsruni in the south.

The Byzantine Empire overthrew Bagratid Armenia in 1045. The other Armenian principalities were soon ruled by the Byzantines as well. The Byzantine era was short-lived, as the Seljuk Empire emerged from the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, defeating the Byzantines and taking control of Armenia.

An Armenian called Ruben I, Prince of Armenia, fled into the Taurus Mountains’ gorges with a few of his fellow countrymen in order to avoid being killed or forced into slavery by people who had killed his relative, Gagik II of Armenia, King of Ani.

The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia was finally founded on January 6, 1198, under the rule of Leo I, King of Armenia, a descendant of Prince Ruben, thanks to the protection of the Byzantine governor of the palace.

Viewing itself as a bulwark of Christianity in the East, Cilicia was a staunch supporter of the European Crusaders. The fact that the Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church, the spiritual head of the Armenian nation, moved his headquarters to the area attests to Cilicia’s centrality in Armenian history and statehood.

The decline of the Seljuk Empire was swift. The Zakarid line of Armenian rulers expelled the Seljuk Turks at the beginning of the 12th century and created Zakarid Armenia, a semi-independent principality that persisted under the Georgian Kingdom’s support in northern and eastern Armenia.

In some regions of the nation, particularly Syunik and Vayots Dzor, the Zakarids and the Orbelian Dynasty shared authority, while the House of Hasan-Jalalyan ruled the provinces of Artsakh and Utik as the Kingdom of Artsakh.

Early Modern times

The Mongol Empire first captured Zakarid Armenia in the 1230s, and thereafter it invaded the whole of Armenia. Other Central Asian tribes, such as the Kara Koyunlu, Timurid dynasty, and Ağ Qoyunlu, which persisted from the 13th century until the 15th century, shortly followed the Mongolian invasions. With repeated invasions that devastated the nation, Armenia eventually grew weaker.

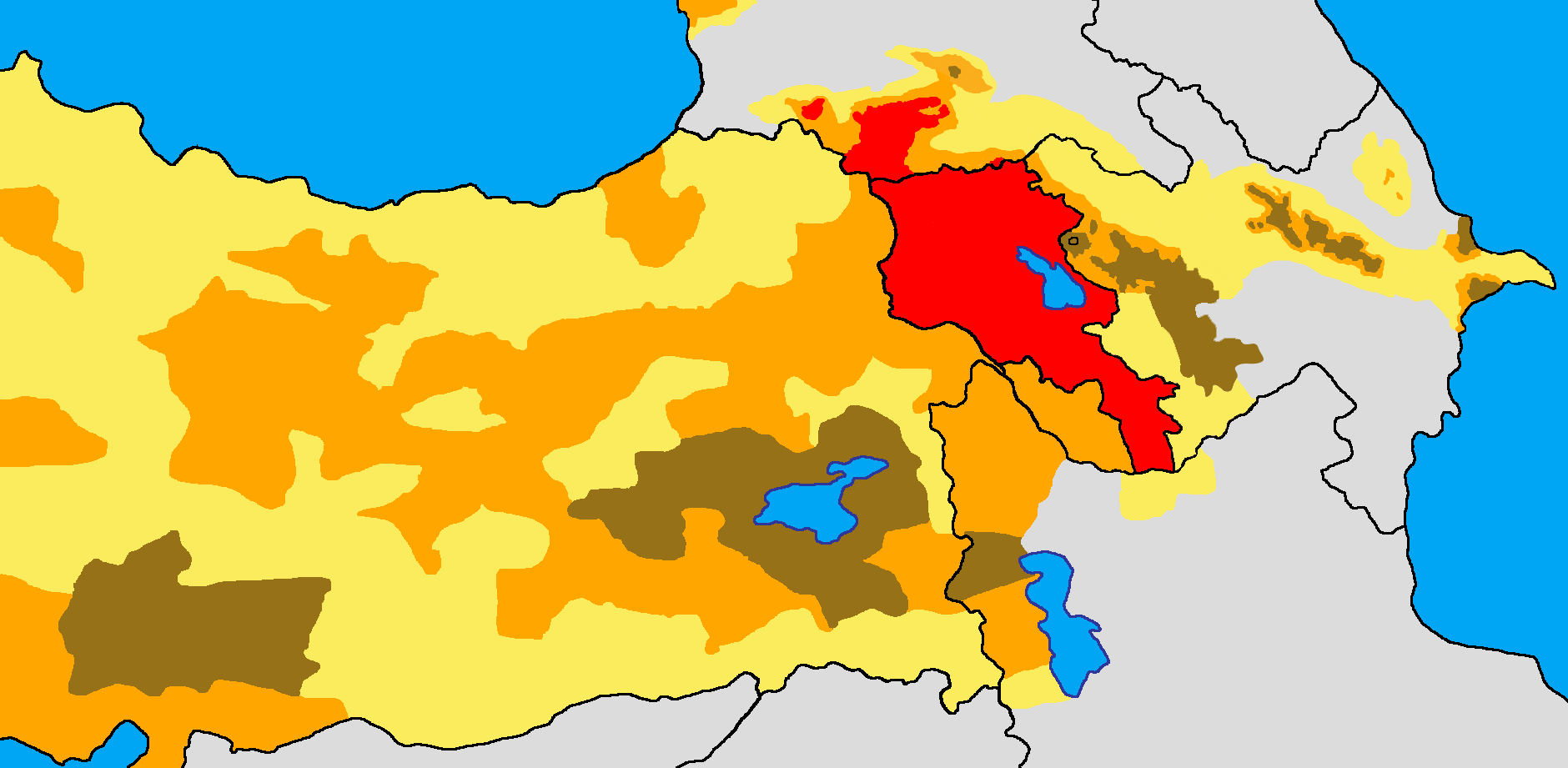

Armenia was partitioned in the sixteenth century by the Safavid dynasty of Iran and the Ottoman Empire. The Safavid Empire conquered both Western and Eastern Armenia starting in the early 16th century. Significant portions of the territory were often battled over by the two rivalling empires during the Ottoman–Persian Wars because of the geopolitical competition between the Turco–Iranian that lasted for a century in West Asia.

Eastern Armenia was ruled by the successive Safavid, Afsharid, and Qajar empires from the mid-16th century with the Peace of Amasya, and decisively from the first half of the 17th century with the Treaty of Zuhab until the first half of the 19th century, with Western Armenia remaining under Ottoman rule.

Abbas I of Iran began implementing the “scorched earth” strategy in 1604, forcing large numbers of Armenians to relocate outside of their native territories in order to defend his northwest frontier against any Ottoman invasion.

The Russo-Persian Wars (1804–13) and (1826–28), respectively, forced the Qajar dynasty of Iran to unconditionally cede Eastern Armenia, which included the Erivan and Karabakh Khanates, to Imperial Russia in the Treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchay (1828). We refer to this era as Russian Armenia.

The Armenians were given significant autonomy inside their own enclaves and coexisted peacefully with other populations in the empire, including the governing Turks, even though Western Armenia was still ruled by the Ottoman Empire. However, Armenians endured widespread prejudice because they were Christians living under a rigid Muslim social order.

Between 1894 and 1896, Sultan Abdul Hamid II organized state-sponsored atrocities against Armenians in retaliation for the Sasun revolt of 1894. Between 80,000 and 300,000 people are said to have died in these massacres. Hamid gained international notoriety as the “Red Sultan” or “Bloody Sultan” as a result of the atrocities known as the “Hamidian massacres.”

In order to defend Armenian villages from massacres that were common in some of the empire’s Armenian-populated areas and to unite the various small groups within the empire that were pushing for reform, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, also known as Dashnaktsutyun, came into being during the 1890s within the Ottoman Empire.

Members of Dashnaktsutyun also founded Armenian fedayi organizations, which used violent resistance to safeguard people who were Armenian. Although they occasionally abandoned this objective in favor of a more practical strategy, such as supporting autonomy, the Dashnaks also worked toward the more general objective of establishing a “free, independent, and unified” Armenia.

As the Ottoman Empire started to fall apart, Sultan Hamid’s administration was toppled in 1908 by the Young Turk Revolution. Up to 20,000–30,000 Armenians may have perished in the Adana massacre, which took place in the Ottoman Empire’s Adana Vilayet in April 1909.

The empire’s Armenian population thought that their inferior status would be lifted by the Committee of Union and Progress. The appointment of an inspector general for Armenian affairs was part of the 1914 Armenian reform package, which was offered as a remedy.

World War I and the Genocide in Armenia

The Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire engaged in combat in the Caucasus and Persian campaigns following the start of World War I. Due to the fact that there was an Armenian volunteer contingent in the Imperial Russian Army, the new administration in Istanbul started to view Armenians with mistrust and suspicion. Armenian intellectuals were detained by Ottoman authorities on April 24, 1915, and when the Tehcir Law was passed on May 29, 1915, a significant number of Anatolian Armenians were eventually killed in what is now known as the Armenian genocide.

The genocide was carried out in two stages: first, the army conscripts were massacred and its able-bodied male population was subjected to forced labor; second, women, children, the elderly, and the sick were deported on death marches toward the Syrian desert.

The deportees, pushed along by military escorts, went without food or water and were frequently the targets of rape, slaughter, and thievery. Local Armenian resistance emerged in the area in opposition to the Ottoman Empire’s actions. Armenians and the great majority of Western historians consider the events of 1915–1917 to have been state-sponsored mass murder, or genocide.

Authorities in Turkey continue to deny that a genocide ever occurred. One of the earliest genocides in contemporary times is widely recognized to have been the Armenian Genocide. Arnold J. Toynbee’s study indicates that between 1915 and 1916, an estimated 600,000 Armenians perished during deportation.

However, this number only includes the first year of the Genocide; it does not account for those who perished or were slain after the report was put up on May 24, 1916. The death toll is estimated at “more than a million” by the International Association of Genocide Scholars. Most estimates place the overall number of deaths between one and 1.5 million.

For more than thirty years, Armenia and the Armenian diaspora have been pushing for the events to be officially recognized as genocide. Every year on April 24, also known as the Day of the Armenian Genocide or Armenian Martyr Day, these events are customarily remembered.

Armenia’s First Republic

Despite taking control of most of Western Armenia during World War I, the Russian Caucasus Army of Imperial forces under Nikolai Yudenich and Armenian volunteers and militia under the leadership of Andranik Ozanian and Tovmas Nazarbekian lost their gains when the Bolshevik Revolution occurred in 1917.

The Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic was an effort at unity at the time between Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Eastern Armenia, all under Russian rule. However, the three parties resolved to dissolve the federation in May 1918, after it had only existed since February. Consequently, on May 28, the Eastern Armenian Dashnaktsutyun administration, led by Aram Manukian, proclaimed themselves the First Republic of Armenia.

During the brief First Republic’s independence, there were several wars, territorial conflicts, large-scale uprisings, and a large-scale inflow of starving and diseased refugees from Western Armenia. Through relief funding and other means, the Entente Powers aimed to assist the recently established state of Armenia.

The winning nations attempted to partition the Ottoman Empire after the war. The Treaty of Sèvres, which was signed on August 10, 1920, in Sèvres between the Ottoman Empire and the Allied and Associated Powers, stipulated that the Armenian republic would continue to exist and that the former Western Armenian territory would be annexed to it.

Western Armenia was also known as “Wilsonian Armenia” since President Woodrow Wilson of the United States was to define the country’s new borders. Furthermore, a few days earlier, on August 5, 1920, Cilicia’s de facto Armenian government, led by Mihran Damadian of the Armenian National Union, proclaimed Cilicia an independent Armenian autonomous republic under French dominion.

The idea of establishing Armenia as a mission under US protection was also entertained. However, the Turkish National Movement opposed the pact, and it was never implemented. The movement replaced the Istanbul-based monarchy with an Ankara-based republic by declaring itself the legitimate government of Turkey on the occasion of the treaty.

Turkish nationalist troops attacked the newly formed Armenian republic from the east in 1920. After the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, Armenian territory was seized by Turkish forces led by Kazım Karabekir, who also took control of the ancient city of Alexandropol (now Gyumri). With the signing of the Treaty of Alexandropol on December 2, 1920, the bloody battle came to an end.

Armenia was compelled by the pact to give up all of the “Wilsonian Armenia” that had been awarded to it at the Sèvres treaty, disband the majority of its armed forces, and relinquish all former Ottoman territory. On November 29, the Soviet Eleventh Army, led by Grigoriy Ordzhonikidze, simultaneously entered Armenia at Karavansarai or modern-day Ijevan.

When Ordzhonikidze’s army arrived in Yerevan on December 4, the short-lived Armenian republic came to an end.

Following the republic’s collapse, the February Uprising occurred shortly after in 1921, and on April 26, Armenian forces led by Garegin Nzhdeh established the Republic of Mountainous Armenia. This region of southern Armenia’s Zangezur region resisted Turkish and Soviet incursions. The insurrection came to an end on July 13 when the Red Army seized control of the area following Soviet negotiations to bring the Syunik Province inside Armenia’s boundaries.

SSR of Armenia

From 1922 to the Second World War

On March 4, 1922, the Transcaucasian SFSR (TSFSR), which included Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan, was merged into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics following Armenia’s annexation by the Red Army. Following this annexation, the Turkish-Soviet Treaty of Kars replaced the Treaty of Alexandropol.

Under the terms of the deal, Turkey gave up authority over the cities of Kars, Ardahan, and Iğdır, which were all a part of Russian Armenia, in exchange for the Soviet Union’s takeover of Adjara, including the port city of Batumi.

The TSFSR was formed in 1922 and lasted until 1936 when it was split into the Armenian SSR, the Azerbaijan SSR, and the Georgian SSR. Armenians lived during a time of relative stability in the USSR, as opposed to the chaotic latter years of the Ottoman Empire.

The church faced challenging circumstances as a result of the USSR’s secular policy. Joseph Stalin, the Communist Party’s general secretary, gradually took control of the USSR when Vladimir Lenin passed away. Millions of people died as a result of the widespread repressions that marked Stalin’s rule across the USSR.

Second World War and the post-Stalinist era

During World War II, there were no engagements fought in Armenia. During the conflict, 175,000 Armenians lost their lives while serving in the Red Army, making up about 500,000 of the country’s total population. Ten non-Armenian persons were among the 117 Armenian citizens who received the Hero of the Soviet Union medal.

Soviet Armenia created six unique military divisions in 1941–1942, in part due to the large number of draftees from the republic who were unable to comprehend Russian. The 89th, 409th, 408th, 390th, and 76th Divisions would go on to have illustrious combat histories; the sixth Division was told to remain in Armenia in order to protect the country’s western frontiers against any Turkish incursions.

Ethnic Armenians made up the 89th Tamanyan Division, which participated in the Battle of Berlin and advanced into the city.

After Nikita Khrushchev became the CPSU’s new general secretary in 1953 and Joseph Stalin passed away, there is a suggestion that the region’s freedom score improved. Life in the SSR of Armenia soon started to rapidly improve. The church, which had suffered during Stalin’s secretaryship, was resurrected in 1955 when Catholicos Vazgen I took up his responsibilities.

A memorial to the victims of the Armenian genocide was constructed in Yerevan in 1967 atop the Tsitsernakaberd hill, which is situated above the Hrazdan valley. This happened following large-scale protests held in 1965 on the occasion of the terrible event’s 50th anniversary.

Gorbachev era

Armenians opposed the pollution that Soviet-built factories brought to their nation and started to demand greater environmental care during the Gorbachev period of the 1980s, with the reforms of Glasnost and Perestroika. Additionally, tensions arose between the majority Armenian territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, which is part of Soviet Azerbaijan’s autonomous district.

In Azerbaijan, there were about 484,000 Armenians in 1970. Karabakh’s Armenian population called for union with Soviet Armenia. Anti-Armenian pogroms in Azerbaijan, like the one in Sumgait, were greeted with nonviolent demonstrations in Armenia in support of the Karabakh Armenians, which in turn sparked anti-Azerbaijani violence in Armenia. Armenia’s issues were made worse in 1988 by a catastrophic earthquake that had a moment magnitude of 7.2.

The failure of Gorbachev to resolve any of Armenia’s issues led to a sense of disappointment among the people, which fueled their rising desire for independence. The New Armenian Army (NAA) was founded in May 1990 to act as a defense force independent of the Soviet Red Army.

When Armenians chose to celebrate the founding of the 1918 First Republic of Armenia, hostilities quickly broke out between the NAA and Soviet Internal Security Forces (MVD) forces stationed in Yerevan. Five Armenians lost their lives as a result of the violence in a gunfight with the MVD at the train station. There were witnesses who said that the MVD started the fight and used excessive force.

Over 26 people, largely Armenians, were killed in additional firefights between Soviet soldiers and Armenian militants in Sovetashen, close to the city. Nearly all 200,000 Armenians living in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, were compelled to leave for Armenia as a result of the pogrom against them that occurred in January 1990.

Armenia proclaimed its autonomy over its territory on August 23, 1990. Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, and the other Baltic nations abstained from a national referendum held on March 17, 1991, during which 78% of voters supported the continuation of the Soviet Union under reform.

Regaining one’s freedom

Following Moscow’s failed August coup attempt, Armenia formally proclaimed its independence on September 21, 1991, RSFSR. On October 16, 1991, Levon Ter-Petrosyan was elected by the people to serve as the first President of the newly established Republic of Armenia. His leadership in the Karabakh movement, which aimed to unite the Armenian-populated region of Nagorno-Karabakh, brought him notoriety. The Soviet Union collapsed on December 26, 1991, and Armenia’s independence was acknowledged.

Alongside Defense Minister Vazgen Sargsyan, Ter-Petrosyan commanded Armenia throughout the First Nagorno-Karabakh War with neighboring Azerbaijan. Economic problems that began early in the Karabakh conflict, when the Azerbaijani Popular Front succeeded in pressuring the Azerbaijan SSR to impose an air and railway embargo against Armenia, characterized the early post-Soviet years. Since trains carried 85% of Armenia’s cargo and supplies, this action essentially crippled the country’s economy. Turkey-backed Azerbaijan by joining the embargo on Armenia in 1993.

In 1994, a ceasefire mediated by Russia brought an end to the Karabakh conflict. The Armenian troops in Karabakh won the conflict, taking control of nearly all of Nagorno-Karabakh as well as 16% of Azerbaijan’s internationally recognized territory. Until 2020, the soldiers supported by Armenia stayed in command of nearly the whole region.

Without a comprehensive settlement, the economies of Armenia and Azerbaijan have suffered, and Armenia’s borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan are still blocked. Over a million people had been displaced and an estimated 30,000 people had died by the time Azerbaijan and Armenia ultimately agreed to a truce in 1994. In the Karabakh war that started later in 2020, thousands of people died.

Geography

Landlocked in the geographical Transcaucasus (South Caucasus) area, Armenia is situated northeast of the Armenian Highlands and between the Black Sea and Caspian Sea in the Southern Caucasus Mountains and their plains. Situated in West Asia, on the Armenian Highlands, it shares borders with Georgia to the north, Iran and Azerbaijan’s exclave of Nakhchivan to the south, and the Lachin corridor—a portion of Lachin District governed by a Russian peacekeeping force—and Azerbaijan proper to the east. Armenia is located between meridians 43° and 47° E and latitudes 38° and 42° N. The Eastern Anatolian montane steppe and Caucasus mixed forests are its two terrestrial ecoregions.

Topographical Features

The total area of Armenia is 29,743 square kilometers or 11,484 square miles. The majority of the area is rugged, with little woods and swift-moving rivers. At Mount Aragats, the ground rises to a height of 4,090 meters (13,419 feet) above sea level; no point is lower than 390 meters (1,280 feet) above sea level. The nation boasts the tenth-highest average elevation in the globe and more mountains—85.9%—than either Nepal or Switzerland.

At 5,137 meters (16,854 feet), Mount Ararat, the tallest mountain in the area, was formerly a part of Armenia. Though it is now in Turkey, Armenians still recognize it as a representation of their homeland. As a result, the mountain still appears on the current Armenian national symbol.

Temperature

Armenia has a distinctly continental highland climate. Summers go from mid-June to mid-September and are hot, dry, and bright. The range of temperatures is 22 to 36 °C (72 to 97 °F). Nonetheless, the impact of the high temperatures is lessened by the low humidity. Cooling and rejuvenating effects are brought about by the evening winds that flow down the mountains. Autumns are lengthy, and springs are short. The leaves of autumn are renowned for being vivid and colorful.

Wintertime temperatures range from −10 to −5 °C (14 to 23 °F), and there is a lot of snowfall. Winter sports fans love to ski Tsaghkadzor’s slopes, which are thirty minutes outside of Yerevan. Nestled in the Armenian highlands, at 1,900 meters (6,234 feet) above sea level, Lake Sevan is the second biggest lake in the world in terms of height.

Environment

According to the Environmental Performance Index (EPI), Armenia came in at number 63 out of 180 nations in 2018. Armenia ranks 109th on the Environmental Health subindex (weighted at 40% in the EPI) and 27th in the world on the Ecosystem Vitality subindex (weighted at 60% in the EPI).

This shows that population health is Armenia’s primary environmental priority, with environmental vitality receiving less attention. Out of all the sub-subindices that go into the Environmental Health subindex, the population’s exposure to air quality is the least satisfactory.

Since none of the 60 landfills in Armenia separate or recycle waste, waste management there is undeveloped. Ten garbage landfills will be able to close after a waste processing plant is built close to Hrazdan city.

The Armenian government is looking into the possibility of building new small modular nuclear reactors, despite recommendations from EU authorities to down the nuclear power station at Metsamor and the abundance of renewable energy sources (particularly hydroelectric and wind power) available in Armenia. The current nuclear reactor is set to undergo refurbishment in 2018 with the aim of improving safety and producing around 10% more electricity.

Finance

Armenians living abroad provide significant financial assistance and investment to the economy. Armenia’s economy was heavily dependent on foreign resources before to its independence and was mostly centered on industry, including chemicals, electronics, equipment, processed food, synthetic rubber, and textiles. The republic had established a sophisticated industrial sector that traded raw resources and energy for manufactured commodities like textiles, machine tools, and other items to sister republics.

Prior to the Soviet Union’s disintegration in 1991, fewer than 20% of the total employment and net material product came from agriculture. Following the country’s independence, agriculture’s economic significance grew significantly, reaching over 30% of GDP and 40% of all jobs by the end of the 1990s.

Due to the population’s need for food security in the face of uncertainty during the early stages of the transition and the collapse of the non-agricultural sectors of the economy in the early 1990s, agriculture has become increasingly important.

Although the percentage of agriculture in employment remained above 40%, the share of agriculture in GDP decreased to just over 20% (according to statistics from 2006) when the economy stabilized and growth restarted.

Lead, gold, zinc, and copper are extracted from Armenian mines. The primary domestic energy source is hydroelectricity; the great majority of energy is produced using fuel imported from Russia, including gas and nuclear fuel (for its only nuclear power plant). Although they are present, small coal, gas, and petroleum resources have not yet been exploited.

Armenia has less access to biocapacity than the global average. Armenia’s biocapacity per person was 0.8 global hectares in 2016, far less than the worldwide average of 1.6 global hectares per person.

Armenia’s ecological footprint of consumption in 2016 was 1.9 global hectares per person. This indicates that they consume twice as much biocapacity as there is in Armenia. Armenia is experiencing a biocapacity shortage as a result.

Armenia’s economy is hampered by the disintegration of previous Soviet trade patterns, just as those of other recently independent former Soviet governments. The Soviet Union’s backing and investments in Armenian industry have all but vanished, leaving just a small number of significant businesses operating today.

Furthermore, 500,000 people are still without a house after the 1988 Spitak earthquake, which claimed over 25,000 lives and left 500,000 more injured. There is still no resolution to the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute with Azerbaijan.

The 1989 nuclear power plant closure was the primary cause of the 1990s energy crisis in Armenia. After the power plant was restarted in 1995, the GDP saw a strong recovery after declining by about 60% between 1989 and 1993.

After being introduced in 1993, the national currency, the dram, experienced hyperinflation during the initial years.

However, the administration succeeded in implementing extensive economic changes that led to a sharp decline in inflation and stable economic development. The economy has also benefited from the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict ceasefire in 1994. Since 1995, Armenia’s economy has expanded rapidly, building on the recovery that started the year before, and inflation has been extremely low for the last few years. More established economic sectors like agriculture are starting to be supplemented by new industries like information and communication technology, tourism, and the manufacturing of precious stones and jewelry.

Armenia is receiving more and more help from foreign organizations as a result of its consistent economic growth. Significant grants and loans are being given by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and other foreign governments and international financial institutions (IFIs).

Over $1.1 billion in loans have been made to Armenia since 1993. The budget deficit and currency stabilization, private company development, energy, agriculture, food processing, transportation, health and education, and continuous restoration in the earthquake zone are the main goals of these loans.

On February 5, 2003, the government became a member of the World Trade Organization. However, the Armenian diaspora continues to be one of the primary sources of foreign direct investments, funding a significant portion of governmental initiatives like as infrastructure repair.

Armenia, as a developing democratic nation, also aspires to receive increased financial support from the West.

In addition to a program of privatizing public property, legislation on privatization was established in 1997 and a liberal foreign investment law was approved in June 1994. The government’s capacity to enhance macroeconomic management—which includes raising revenue collection, enhancing the investment climate, and taking action against corruption—will determine how far it can go in terms of progress. Still, a significant issue with unemployment, which reached 18.5% in 2015, is the thousands of refugees fleeing the Karabakh conflict.

The economy expanded by 7.5% in 2017 as a result of increased copper prices.

According to Heritage Organization, Armenia’s GDP was $39.4 billion in 2022 and its economic freedom score was 65.3.

The massive migration of Russian nationals is expected to propel the Armenian economy into a 13% growth rate by 2022. As of March 2022, the IMF’s preliminary prediction called for 1.5% annual growth.

Technology and science

Armenia spent a meager 0.25% of GDP on research on average between 2010 and 2013. However, because research expenditures by privately held businesses are not polled in Armenia, the statistical record of research expenditures is insufficient. In 2013, the global average for domestic research spending as a percentage of GDP was 1.7%.

“By 2020, Armenia is a country with a knowledge-based economy and is competitive within the European Research Area with its level of basic and applied research,” according to the nation’s Strategy for the Development of Science 2011–2020. It addresses the following issues:

- Establishment of a framework that may support the advancement of science and technology;

- Growth of scientific potential and infrastructure upgrade in science;

- Encouragement of fundamental and practical research

- Building a system of education, research, and innovation that works in concert; and

- Become one of the top destinations in the European Research Area for specialized scientific research.

In June 2011, the government adopted the associated Action Plan based on this plan. It outlines the following objectives:

- Enhance the science and technology management system and establish the prerequisites for sustainable growth;

- Increase the number of youthful, gifted individuals engaged in education and research while modernizing research facilities;

- Establish the prerequisites for the establishment of a comprehensive national innovation system; and

- Promote global collaboration in the field of research and development.

It is evident that the Strategy has a “science push” stance, with public research institutes as the primary policy focus, but it also makes reference to the establishment of an innovation system. Nevertheless, the business sector—which is the primary force behind innovation—is left out.

The government released a resolution on Science and Technology Development Priorities for 2010–2014 in May 2010, in between the publication of the Strategy and Action Plan. These order of importance is:

- Humanities, social sciences, and studies of Armenia;

- Biological sciences

- Innovative and renewable energy sources;

- Cutting-edge and information technology;

- Earth sciences, space exploration, environmentally friendly resource usage, and fundamental research that supports crucial applied research.

May 2011 saw the adoption of the National Academy of Sciences Law. It is anticipated that the Armenian innovation system will be significantly shaped by this law. It makes provisions for restructuring the National Academy of Sciences by uniting institutes engaged in closely related research areas into a single body.

It also permits the National Academy of Sciences to expand its business activities to include the commercialization of research results and the creation of spin-offs. The Center for Biotechnology, the Center for Zoology and Hydro-ecology, and the Center for Organic and Pharmaceutical Chemistry are three of these new centers that are especially noteworthy.

The government is giving specific manufacturing sectors its full backing. The State Committee of Science has co-funded over 20 projects in the following targeted fields: electronics, engineering, chemistry, pharmaceuticals, medicine and biotechnology, agricultural mechanization and machine building, electronics, engineering, and information technology in particular.

The government has worked to promote industry-science ties during the last ten years. The information technology industry in Armenia has been quite active, with many public-private partnerships formed between businesses and academic institutions to help students develop employable skills and produce creative ideas at the nexus of science and business. Synopsys Inc. and the Enterprise Incubator Foundation are two examples. Armenia dropped from 64th place in 2019 to 72nd place in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.

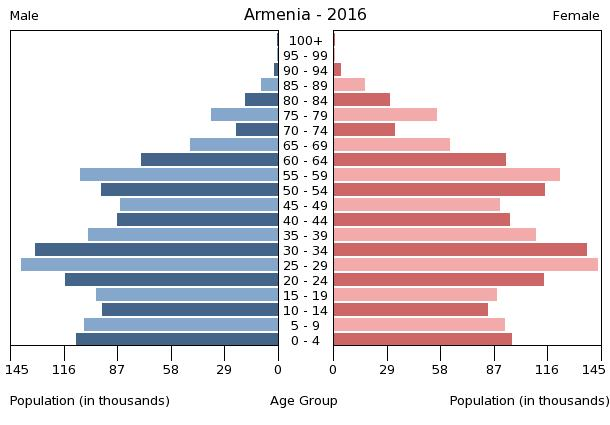

Characteristics

As of 2022, Armenia has 2,932,731 inhabitants, making it the third most densely populated former Soviet country. Since the USSR broke up, there has been a concern with population reduction as a result of high emigration rates. The rate of emigration has decreased recently, and since 2012, there has been some population increase.

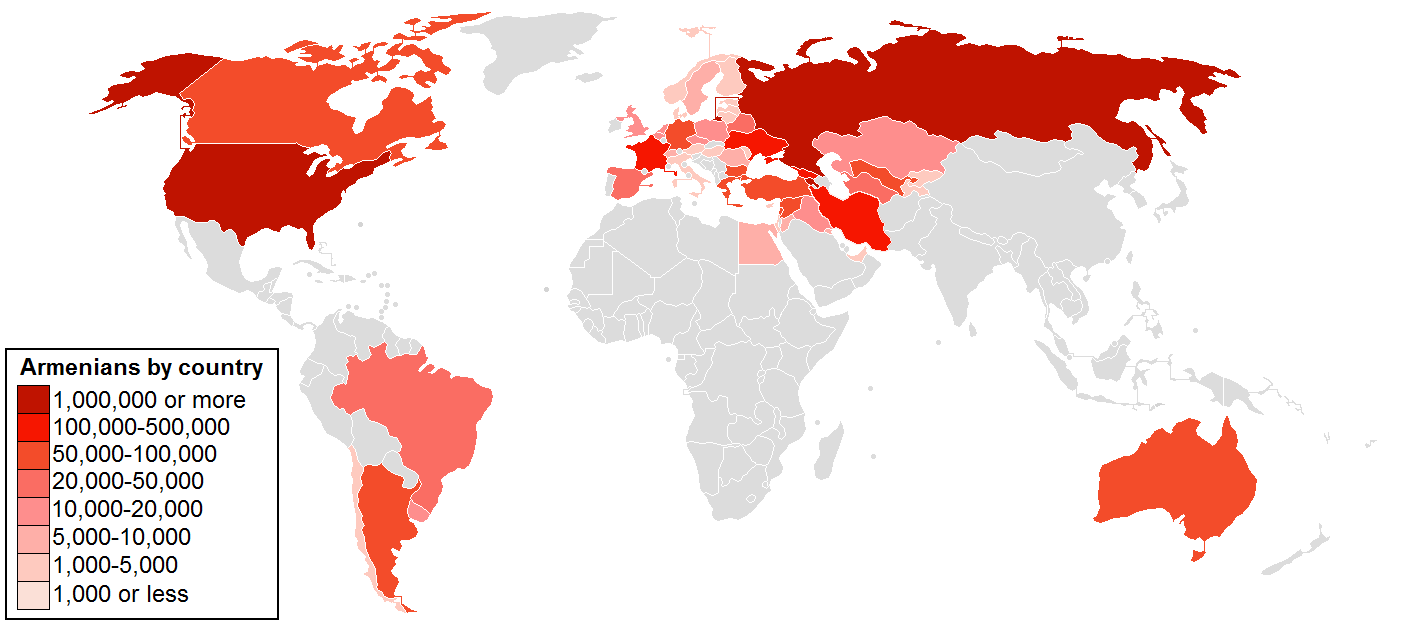

With populations spread around the globe, Armenia has a sizable foreign diaspora (8 million by some estimates, much exceeding the 3 million population of Armenia itself). The countries with the greatest Armenian populations outside of Armenia include Brazil, Georgia, Syria, Lebanon, Georgia, France, Iran, Russia, Australia, Canada, Greece, Cyprus, Israel, Poland, and Ukraine. There are still between 40,000 and 70,000 Armenians in Turkey, primarily in and around Istanbul.

The Armenian Quarter in Jerusalem’s Old City is home to about 1,000 Armenians, who are the surviving members of a once-larger population. The Mechitarists, an Armenian Catholic congregation, operate a monastery entirely on the island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni in the Venetian Lagoon in Italy.

Before October 1, 2023, when nearly all of the region’s inhabitants fled to Armenia, the bulk of the roughly 139,000 Armenians living in the de facto independent country of the Republic of Artsakh were Armenians.

Groups of ethnic people

Ninety-eight percent of the population is ethnic Armenian. Russians comprise up 0.5% and Yazidis 1.1%. Assyrians, Ukrainians, Greeks (often referred to as Caucasus Greeks), Kurds, Georgians, Belarusians, and Jews are among the other communities.

Smaller Vlach, Mordvin, Ossetians, Udis, and Tat populations are also present. Although they have been severely Russified, there are also small populations of Caucasus Germans and Poles. In Armenia, there were 31,077 Yazidis as of 2022.

With 76,550 inhabitants in 1922 and around 2.5% of the total in 1989, Azerbaijanis were historically the second biggest population in the nation throughout the Soviet era. But almost all of them left Armenia for Azerbaijan as a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. On the other hand, a significant number of Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan arrived in Armenia, giving the country a more uniform population.

According to a 2017 Gallup study, Armenia has one of the greatest rates of migrant acceptance (welcoming) in Eastern Europe.