Born:- 20 or 21 July 356 BC

Death:- 10 or 11 June 323 BC (aged 32)

Known by most as Alexander the Great, Alexander III of Macedon (Ancient Greek: Ἀλέξαν΅ρoς, romanized: Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC) was a monarch of the Macedonian state. At the age of 20, he took the kingdom from his father Philip II in 336 BC. During the majority of his reign, he led a protracted military campaign over Egypt, sections of South Asia, Central Asia, and Western Asia. He established one of the biggest empires in history by the time he was thirty years old, spanning from Greece to northwest India. He is regarded as one of the best and most accomplished military leaders in history because of his perfect record in combat.

Aristotle educated Alexander until he was sixteen years old. Shortly after taking up the throne in Macedonia in 335 BC, he launched a Balkan expedition, reclaiming Thrace and portions of Illyria before advancing on Thebes, which was ultimately destroyed in combat. Subsequently, Alexander headed the League of Corinth and employed his power to initiate the pan-Hellenic initiative envisioned by his father. He also took charge of leading all Greeks in their invasion of Persia.

He launched an assault on the Achaemenid Persian Empire in 334 BC, the first of ten years of wars. After capturing Asia Minor, Alexander defeated Achaemenid Persia in several key engagements, including as those at Issus and Gaugamela. He then deposed Darius III and took control of the Achaemenid Empire as a whole. The Macedonian Empire ruled over a sizable area of land between the Adriatic Sea and the Indus River following the collapse of Persia. Alexander set out to conquer the “ends of the world and the Great Outer Sea” and invaded India in 326 BC. At the Battle of the Hydaspes, he decisively defeated Porus, an ancient Indian monarch of modern-day Punjab.

He finally turned back at the Beas River in response to the demands of his soldiers, who were pining for their own land and died in Babylon in 323 BC, in Mesopotamia, the city he intended to construct as the capital of his kingdom. Following Alexander’s death, a number of other planned military and commercial efforts that were to have started with a Greek invasion of Arabia were not carried out. Following his passing, the Macedonian Empire saw several civil conflicts that finally resulted in the Diadochi’s destruction of the empire.

Alexander’s legacy includes the cultural spread and syncretism that his conquests fostered, such as Greco-Buddhism and Hellenistic Judaism, with his death signaling the beginning of the Hellenistic period. He established almost two dozen towns, the most well-known of which being Alexandria, Egypt. Greek immigrants were sent to India by Alexander, and Greek culture flourished as a result, giving Hellenistic civilization enormous domination and influence that reached as far east as the Indian subcontinent. Greek became the regional tongue and the main language of the Byzantine Empire until its fall in the middle of the fifteenth century AD. The Hellenistic era gave rise to current Western culture through the Roman Empire.

Alexander rose to fame as a classical hero akin to Achilles, making frequent appearances in the historical and legendary narratives of both Greek and non-Greek societies. Many other military commanders would measure themselves against him because of his military prowess and extraordinary long-lasting victories in combat, and his strategies are still studied at military colleges throughout the globe. Stories of Alexander’s adventures came together to form the Alexander Romance of the third century. During the premodern era, this narrative underwent more than a hundred recensions, translations, and derivatives, and it was translated into nearly every European dialect and every language spoken in the Islamic world. It was the most widely read genre in European literature, just after the Bible.

Early Years

Family History and Early Life

Alexander III was born on the sixth day of the ancient Greek month of Hekatombaion at Pella, the capital city of the Kingdom of Macedon. This date is unknown, although it likely corresponds to July 20, 356 BC. His parents were Philip II, the former king of Macedonia, and Olympias, his fourth wife, who was the daughter of Neoptolemus I, the king of Epirus. Despite having seven or eight wives overall, Olympias served as Philip’s primary spouse for a while, most likely because she gave birth to Alexander.

There are several myths about Alexander’s conception and early years. The dream that Olympias had on the eve of her marriage to Philip ended with a thunderbolt striking her womb and a flame spreading “far and wide” before going out, according to the ancient Greek writer Plutarch. Philip is reported to have dreamed, at some point after the wedding, of himself sealing his wife’s womb with a seal with the image of a lion. Plutarch provided a number of explanations for these visions, including the notion that Alexander’s father was Zeus and that Olympias was pregnant before she was married, as shown by the closure of her womb.

Commentators from antiquity differed over whether Olympias, who was ambitious, spread the tale of Alexander’s divine lineage. Some said that Olympias had told Alexander about it, while others regarded the idea as sacrilegious.

Philip was prepared to lay siege to Potidea, a city located on the Chalcidice peninsula, on the day Alexander was born. Philip learned the same day that his general Parmenion had won the Olympic Games with his horses and that the united Illyrian and Paeonian army had been routed. Additionally, it was reported that one of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, burned and destroyed on this day. As a result, Hegesias of Magnesia said that it burned down because Artemis was gone attending Alexander’s birth. Legends of this kind may have arisen during Alexander’s reign, maybe even at his request, to demonstrate his superhuman abilities and predestined grandeur from birth.

Early on, Alexander was taken care of by a nurse named Lanike, who happened to be the sister of Alexander’s future commander, Cleitus the Black. Later in his early years, Lysimachus of Acarnania and his mother’s uncle Leonidas, who was rigorous, instructed Alexander. Raised in the way of virtuous Macedonian lads, Alexander learned to ride, fight, hunt, study, and play the lyre. A Thessalian dealer brought Philip a horse when Alexander was ten years old, which he offered to sell for thirteen talents. Philip gave the order to put the horse away since it would not mount. But Alexander saw the horse was afraid of its own shadow and begged to tame it, which he finally did.

According to Plutarch, ecstatic by his son’s bravery and ambition, Philip gave him a heartfelt kiss and said, “My boy, you have to find a kingdom big enough for your ambitions.” “Macedon is too small for you,” they said, and he got him the horse. “Ox-head” is how Alexander dubbed it, Bucephalas. Alexander was transported by Bucephalas as far as India. At the age of thirty, the beast passed away from old age (according to Plutarch), and Alexander named the city Bucephala in his honor.

Learning

When Alexander was thirteen, Philip started looking for a teacher. He looked at scholars like Isocrates and Speusippus, the latter of whom offered to give up his position as steward of the Academy in order to take on the role. Philip ultimately decided on Aristotle and made the Mieza Temple of the Nymphs available as a school. Philip promised to reconstruct Aristotle’s hometown of Stageira, which he had destroyed, and to repopulate it by purchasing and releasing the slaves who were formerly citizens or by pardoning those who had been exiled in exchange for educating Alexander.

For Alexander and the offspring of Macedonian nobility like Ptolemy, Hephaistion, and Cassander, Mieza served as akin to a boarding school. Many of these students—often referred to as the “Companions”—went on to become his pals and future generals. Alexander and his friends learned about logic, art, religion, morality, philosophy, and medicine from Aristotle. Alexander became passionate about Homer’s writings under Aristotle’s guidance, especially the Iliad. Aristotle handed Alexander an annotated copy of the Iliad, which Alexander subsequently took with him on his expeditions. Alexander could recite a passage from Euripides from memory.

During his childhood, Alexander also knew Persian refugees at the Macedonian court who were shielded from Artaxerxes III for a number of years by Philip II. Among them were Artabazos II and his daughter Barsine, who lived at the Macedonian court from 352 to 342 BC and was a potential mistress of Alexander; other notables were Amminapes, who was Alexander’s future satrap, and Sisines, a Persian aristocrat. This provided the Macedonian court with a solid understanding of Persian matters and could possibly have had an impact on some of the advances in Macedonian state administration.

According to Suda, Alexander studied under Anaximenes of Lampsacus, who also accompanied Alexander on his wars.

Successor of Philip II

Regency and ascent of Macedon

Alexander finished his studies with Aristotle when he was sixteen years old. Alexander became regent and heir apparent after Philip II’s campaign against the Thracians to the north. The Maedi tribe of Thracians rose up in rebellion against Macedonia while Philip was away. Swiftly taking action, Alexander expelled them from their domain. After the area was settled, the city of Alexandropolis was established.

Alexander was sent with a small force to quell the uprisings in southern Thrace when Philip returned. Alexander is said to have rescued his father’s life by leading an army against the Greek city of Perinthus. Philip had the chance to further meddle in Greek politics when the city of Amphissa started to work areas near Delphi that were holy to Apollo. Alexander was given the task of gathering an army for a war in southern Greece while Philip was busy in Thrace. Alexander, fearing intervention from other Greek nations, gave the impression that he was getting ready to invade Illyria instead. The Illyrians attempted to conquer Macedonia during this upheaval, but Alexander drove them back.

After putting up a valiant fight against its Theban garrison, Philip and his army marched south through Thermopylae to reunite with his son in 338 BC. They proceeded to seize control of Elatea, which was just a short distance from Thebes and Athens. Under Demosthenes’ leadership, the Athenians decided to form an alliance with Thebes to oppose Macedonia. Philip and Athens each dispatched envoys to court Thebes, but Athens emerged victorious. Presumably responding to an Amphictyonic League request, Philip marched on Amphissa, captured the mercenaries Demosthenes had dispatched there, and acknowledged the city’s capitulation. After that, Philip went back to Elatea and sent one more peace proposal to Thebes and Athens, both of which turned it down.

Philip’s opponents stopped him mid-marching south of Chaeronea, Boeotia. In the subsequent Battle of Chaeronea, Alexander led the left wing while Philip, supported by some of Philip’s reliable generals, commanded the right. The ancient accounts describe a protracted period of fierce fighting between the two sides. In order to break the line of the untested Athenian hoplites, Philip purposefully ordered his forces to retire. Theban lines were first breached by Alexander, then by the generals of Philip. After weakening the enemy’s unity, Philip gave the command for his forces to advance, swiftly destroying them. The Thebans were encircled after the Athenians were defeated. When left to battle on their own, they lost.

Following their triumph at Chaeronea, Philip, and Alexander entered the Peloponnese without encountering any resistance, wreaking havoc on a large portion of Laconia and driving the Spartans from several regions. Philip formed the “Hellenic Alliance” at Corinth, which comprised all of the Greek city-states save Sparta and was modeled after the previous anti-Persian coalition during the Greco-Persian Wars. At that point, Philip declared his intention to invade the Persian Empire and was given the title of Hegemon, which is sometimes translated as “Supreme Commander” of this alliance (today called the alliance of Corinth by contemporary researchers).

Banished and then Brought Back

After arriving back in Pella, Philip fell in love with and wed Cleopatra Eurydice (338 BC), his commander Attalus’s niece. Alexander was only half-Macedonian, hence the marriage made his status as heir less certain. Any offspring of Cleopatra Eurydice would be a completely Macedonian heir. An inebriated Attalus openly appealed to the gods during the wedding feast, hoping that the union might result in a rightful successor.

At the wedding of Cleopatra, whom Philip fell in love with and married, she being much too young for him, her uncle Attalus in his drink desired the Macedonians would implore the gods to give them a lawful successor to the kingdom by his niece. This so irritated Alexander that throwing one of the cups at his head, “You villain,” said he, “what, am I then a bastard?” Then Philip, taking Attalus’s part, rose up and would have run his son through; but by good fortune for them both, either his over-hasty rage or the wine he had drunk, made his foot slip, so that he fell down on the floor, at which Alexander reproachfully insulted him: “See there,” said he, “the man who makes preparations to pass out of Europe into Asia, overturned in passing from one seat to another.”

— Plutarch, describing the feud at Philip’s wedding.

Alexander and his mother left Macedonia in 337 BC, leaving her in the care of her brother, King Alexander I of Epirus, at the Molossian capital of Dodona. Having vanquished them in combat a few years prior, he proceeded to Illyria where he sought sanctuary with one or more Illyrian monarchs, maybe Glaucias. There, he was received as a guest. Philip, it seems, never meant to deny his son’s political and military training. As a result, six months later, Alexander made his way back to Macedon thanks to the mediation efforts of Demaratus, a family friend.

The next year, Philip Arrhidaeus, Alexander’s half-brother, accepted an offer from Pixodarus, the Persian satrap (administrator) of Caria, for his eldest daughter. This, according to Olympias and a few of Alexander’s associates, demonstrated Philip’s intention to name Arrhidaeus his heir.

In response, Alexander dispatched Thessalus of Corinth, an actor, to advise Pixodarus to present his daughter’s hand to Alexander rather than an illegitimate son. Upon learning of this, Philip halted the discussions and chastised Alexander for wanting to wed a Carian’s daughter, stating that he had higher standards for a spouse. Four of Alexander’s comrades were banished by Philip: Harpalus, Nearchus, Ptolemy, and Erigyius. Thessalus was brought to Philip in chains by the Corinthians.

Macedonian King

Accession

The captain of Philip’s bodyguards, Pausanias, killed him on the 24th day of the Macedonian month Dios, which is most likely October 25, 336 BC, while he was at Aegae attending his daughter Cleopatra’s marriage to Alexander I of Epirus, Olympias’ brother. Pausanias was being followed by Perdiccas and Leonnatus, two of Alexander’s friends, when he stumbled on a vine and died. At the age of 20, Alexander was immediately crowned king by the nobility and military.

Concentration of Power

Alexander started his rule by putting an end to any contenders for the throne. He had the former Amyntas IV, his cousin, put to death. In addition, he executed two Macedonian princes from the Lyncestis area for their roles in his father’s murder, but he spared Alexander Lyncestes, the third. Europa, Cleopatra’s daughter with Philip, and Eurydice were set ablaze by Olympias. Alexander was enraged to hear about this. Alexander also gave the order to kill Cleopatra’s uncle, Attalus, who oversaw the army’s advance guard in Asia Minor.

Demosthenes and Attalus were communicating at the time about Attalus’ potential desertion to Athens. In addition, Attalus had insulted Alexander harshly, and once Cleopatra was killed, Alexander could have concluded that Attalus was too dangerous to be left alive. Arrhidaeus, by all accounts mentally crippled, maybe from Olympias’ poisoning, was spared by Alexander.

Many nations, notably Thebes, Athens, Thessaly, and the Thracian tribes north of Macedon rose up in rebellion upon hearing of Philip’s death. Alexander was swift to react after learning of the uprisings. Alexander gathered 3,000 Macedonian cavalry and headed southward against Thessaly despite being persuaded to utilize diplomacy. Ordering his warriors to ride across Mount Ossa, he discovered that the Thessalian army was occupying the pass between Mount Olympus and Mount Olympus.

Thessalonicians awakened the following day to find Alexander behind them. They quickly submitted, joining Alexander’s army with their cavalry. Next, he headed south in the direction of the Peloponnese.

Before continuing south to Corinth, Alexander made a halt at Thermopylae, where he was acknowledged as the Amphictyonic League’s leader. Alexander granted Athens’ request for peace by pardoning the rebels. Alexander was visiting Corinth when he had the renowned encounter with Diogenes the Cynic.

Diogenes scornfully advised Alexander to go to the side as he was obstructing the sunshine when Alexander asked him what he could do for him. Alexander is supposed to have been thrilled by this response and remarked, “But verily, if I were not Alexander, I would like to be Diogenes.” Alexander, like Philip, assumed the title of Hegemon (“leader”) at Corinth and was named commander of the next battle against Persia. There was also word of a revolt among the Thracians.

Balkan offensive

Alexander sought to secure his northern boundaries before traveling to Asia. He moved forward in the spring of 335 BC to put down many uprisings. He left Amphipolis and proceeded eastward into the territory of the “Independent Thracians,” where the Macedonian army fought and routed the Thracian soldiers garrisoned on Mount Haemus. Near the Lyginus River, a branch of the Danube, the Macedonians routed the Triballi army after marching into their land. After that, Alexander marched for three days to the Danube, where he came upon the Getae tribe on the other side. After the first cavalry engagement, he surprised them by crossing the river at night and drove their army to escape.

Alexander then received word that King Glaukias of the Taulantii and the Illyrian chieftain Cleitus were openly defying him. Alexander routed both as he marched westward into Illyria, sending the two kings and their armies running for their lives. He established his northern boundary with these conquests.

Thebes’ destruction

Thebans and Athenians revolted once more while Alexander waged a war to the north. Alexander went south right away. Thebes chose to battle while the other towns hesitated once again. Alexander destroyed the city and distributed its land among the other Boeotian cities when the Theban resistance proved to be futile. All of Greece experienced a brief period of calm after Thebes’ demise intimidated Athens. Antipater took over as regent when Alexander left on his Asian campaign.

Achaemenid Persian Empire conquest

Asia Minor

Following his triumph in the Chaeronea battle (338 BC), Philip II set about assuming the role of hēgemṓn (Greek: ἡγεμώv) of a league. Diodorus states that the league’s mission was to fight the Persians for the various grievances Greece had in 480 and to liberate the Greek cities on the western coast and islands from Achaemenid rule. To prepare for an invasion, he dispatched Parmenion, Amyntas, Andromenes, Attalus, and an army of 10,000 men to Anatolia in 336. The Greek cities on Anatolia’s western shore revolted until word spread that Philip, his infant son Alexander, had been assassinated.

After Philip’s death, the Macedonians lost hope and were routed by the Achaemenids, led by the hired gun Memnon of Rhodes, in the vicinity of Magnesia.

Taking over Philip II’s invasion project, Alexander’s army crossed the Hellespont in 334 BC with roughly 48,100 soldiers, 6,100 cavalry, and a fleet of 120 ships, with 38,000 crew members comprised of mercenaries, soldiers from Thrace, Paionia, and Illyria, as well as soldiers raised feudally. He said that he had taken Asia as a gift from the gods and threw a spear into Asian soil, indicating his intention to subjugate the whole Persian Empire. This further demonstrated Alexander’s desire for combat as opposed to his father’s inclination toward diplomacy.

Following his first triumph against Persian soldiers at the Battle of the Granicus, Alexander went along the Ionian coast, offering the cities sovereignty and democracy, and accepted the surrender of Sardis, the Persian regional seat and treasury. A careful siege campaign was needed to free Miletus from Achaemenid troops, with Persian naval forces in close proximity. Alexander successfully conducted his first extensive siege at Halicarnassus in Caria, further to the south. In the end, he forced his opponents, the Persian satrap of Caria, Orontobates, and the mercenary commander Memnon of Rhodes, to retreat by sea. Ada, a member of the Hecatomnid dynasty, took over as Caria’s ruler after Alexander’s death.

Alexander advanced from Halicarnassus into the Pamphylian plain and hilly Lycia, claiming dominion over all coastal cities to deny the Persians access to naval bases. Alexander proceeded inland as there were no significant ports along the coast beyond Pamphylia. Alexander submitted at Termessos and refrained from overrunning the Pisidian city. Alexander “undid” the Gordian Knot, which had stood unsolved until then, at the ancient Phrygian city of Gordium. This achievement is supposedly reserved for the future “king of Asia”. Alexander, according to legend, chopped the knot apart with his sword, declaring that it did not matter how it was undone.

Syria and the Levant

Alexander crossed the Taurus into Cilicia in the spring of 333 BC. He marched in the direction of Syria after a protracted illness-related hiatus. Despite being outclassed by Darius’s far bigger force, he marched back to Cilicia and beat Darius at Issus. Darius left behind his mother Sisygambis, his two children, his wife, and an incredible fortune when he fled the fight, which contributed to the defeat of his army.

He proposed a ransom of 10,000 talents for his family in exchange for a peace treaty that included the territory he had already lost. Alexander retorted that he alone made decisions on the division of territory because he was now king of Asia. Alexander went on to conquer Syria and the majority of the Levantine coast.

He was compelled to assault Tyre the next year, 332 BC, and eventually succeeded in taking it after a protracted and challenging siege. Women and children were sold into slavery, while males of military age were massacred.

Egypt

The majority of the villages along the way to Egypt promptly submitted after Alexander devastated Tyre. But in Gaza, Alexander encountered opposition. A siege was necessary since the castle was steeply walled and perched on a hill. After “his engineers pointed out to him that because of the height of the mound, it would be impossible… this encouraged Alexander all the more to make the attempt”. The fortress finally gave way after three fruitless attempts, but not before Alexander suffered a critical injury to his shoulder. Men of military age were executed by hanging, while women and children were sold into slavery, much like in Tyre.

Just one of the many lands that Alexander wrested from the Persians was Egypt. Alexander was crowned in Memphis’s Temple of Ptah following his journey to Siwa. It seems that neither his foreign origin nor the fact that he was away for almost the all of his reign alarmed the Egyptian populace.

Alexander erected new monuments honoring the Egyptian gods and renovated the temples that the Persians had abandoned. He constructed a chapel for the holy barge at the Luxor temple, which is close to Karnak. He arranged the military takeover of Egypt and changed the taxing system after studying Greek models during his few months there, but he sailed for Asia in early 331 BC to pursue the Persians.

Just one of the many lands that Alexander wrested from the Persians was Egypt. Alexander was crowned in Memphis’s Temple of Ptah following his journey to Siwa. It seems that neither his foreign origin nor the fact that he was away for almost the all of his reign alarmed the Egyptian populace. Alexander erected new monuments honoring the Egyptian gods and renovated the temples that the Persians had abandoned.

He constructed a chapel for the holy barge at the Luxor temple, which is close to Karnak. He arranged the military takeover of Egypt and changed the taxing system after studying Greek models during his few months there, but he sailed for Asia in early 331 BC to pursue the Persians.

Later in 332 BC, Alexander invaded Egypt, where people saw him as a liberator. Alexander offered sacrifices to the gods at Memphis in order to gain legitimacy for his ascension to power and recognition as a descendant of the ancient pharaohs. He also traveled to the Siwa Oasis in the Libyan desert to consult the renowned Amun-Ra oracle, where he was declared to be the son of the god Amun.

From that point on, Alexander frequently referred to Zeus-Ammon as his real father. Following his passing, coins featuring him with horns were created, utilizing the Horns of Ammon as a representation of his deity. The gods sent this word to all the pharaohs, and the Greeks saw it as a prophesy.

He established Alexandria while he was in Egypt, and it would grow to be the thriving capital of the Ptolemaic Kingdom after his passing. Following Alexander’s death, Ptolemy I (son of Lagos), the Ptolemaic Dynasty’s founder (305–30 BC), inherited control of Egypt.

Assyria and Babylonia

After leaving Egypt in 331 BC, Alexander advanced eastward into Upper Mesopotamia, or modern-day northern Iraq, and triumphed against Darius once more at the Battle of Gaugamela. Darius ran off of the field again, and Alexander followed him all the way to Arbela. Gaugamela would be their last and most important meeting. While Alexander was capturing Babylon, Darius escaped across the mountains to Ecbatana or modern-day Hamadan.

According to Babylonian astrological journals, “the king of the world, Alexander” sent his scouts into the city ahead of time, telling the populace, “I shall not enter your houses.”

Iran

Alexander traveled from Babylon to Susa, one of the Achaemenid capital cities, and took control of its coffers. He used the Persian Royal Road to send the majority of his army to Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of Persia. Alexander personally led a small group of soldiers to the city by the straight path. After overpowering a Persian army led by Ariobarzanes to shut the Persian Gates pass (located in the present-day Zagros Mountains), he rushed to Persepolis to avoid its garrison pilfering the treasure.

Alexander let his army plunder Persepolis for several days after they arrived. Alexander spent five months living in Persepolis. Xerxes I’s eastern palace caught fire during his visit, and the fire quickly spread over the entire city. Possible origins include an intoxicated accident or intentional retaliation for Xerxes’ destruction of the Acropolis of Athens during the Second Persian War; Plutarch and Diodorus claim that Thaïs, Alexander’s hetaera companion, set the fire. Alexander quickly regretted his choice, even as he watched the city burn. According to Plutarch, when he gave the order for his soldiers to put out the fires, the majority of the city was already engulfed in flames.

Alexander, according to Curtius, did not regret his choice until the following morning. According to a story told by Plutarch, Alexander stops and addresses a Xerxes statue that has fallen as though it were a real person:

Should I just walk by and leave you lying there because of the battles you fought against Greece, or should I use your generosity and other virtues to rebuild your strength?

Decline of the Eastern and Persian Empires

After that, Alexander pursued Darius into Media and then Parthia. The Persian monarch lost control over his own fate and was captured by his kinsman and Bactrian satrap, Bessus. Bessus had his soldiers stab the Great King to death as Alexander drew near. He then proclaimed himself Artaxerxes V, the heir to Darius, and withdrew into Central Asia to begin a guerilla war against Alexander. In a stately burial, Alexander interred Darius’s bones near to those of his Achaemenid forebears. He said that Darius had designated him as the Achaemenid king’s heir while he was dying. Most people agree that Darius was the catalyst for the demise of the Achaemenid Empire.

But insofar as Alexander preserved and revived the fundamental institutions of society and the political system throughout his own reign, the Iranologist Pierre Briant notes that he “may therefore be considered to have acted in many ways as the last of the Achaemenids.”

Alexander went out to destroy Bessus because he saw him as a usurper. Originally intended to defeat Bessus, this mission evolved into a massive trip across central Asia. Alexander established a number of new cities that he named Alexandria, notably Alexandria Eschate (“The Furthest”) in present-day Tajikistan and modern-day Kandahar in Afghanistan. Alexander traveled to Drangiana, Arachosia (South and Central Afghanistan), Bactria (North and Central Afghanistan), Scythia, Media, Parthia, and Aria (West Afghanistan).

Bessus was put to death in 329 BC after Spitamenes, an ambiguous official in the Sogdiana satrapy, betrayed him to Ptolemy, one of Alexander’s closest allies. But later on, when Alexander was on the Jaxartes fending off an army of horse nomads, Spitamenes staged an uprising in Sogdiana. At the Battle of Jaxartes, Alexander personally vanquished the Scythians. He then launched an assault against Spitamenes, ultimately defeating him at the Battle of Gabai. Following the loss, Spitamenes’ own soldiers executed him and demanded peace.

The Khalili Collection of Aramaic Documents contains an administrative document from Bactria that dates to the seventh year of Alexander’s reign (324 BC) and is the earliest instance of the name “Alexandros” being used.

Issues and schemes

During this period, Alexander brought various aspects of Persian attire and traditions to his court, most notably the proskynesis habit, which involved prostrating oneself on the ground or giving a symbolic kiss to one’s superiors in society. This was a single facet of Alexander’s comprehensive plan to win the favor and cooperation of the elites in Iran. Nonetheless, the Greeks considered proskynesis to be the domain of gods, and they thought Alexander intended to become a god by mandating it. Many of his compatriots lost sympathy for him as a result, and he finally gave it up.

Throughout the lengthy Achaemenid dynasty, prominent roles in the army, the central administration, and the numerous satrapies were exclusively held by Iranians and, to a large extent, Persian noblemen. The latter were frequently further linked by matrimonial connections with the Achaemenid royal line. Alexander was faced with the dilemma of whether to utilize the different groups and individuals who had contributed to the empire’s stability and cohesion over an extended duration.

Knowing this, he attacked ruler Darius III of the time “by appropriating the main elements of the Achaemenid monarchy’s ideology, particularly the theme of the king who protects the lands and the peasants” in 334 BC. In a 332 BC letter to Darius III, Alexander made the case that he was more deserving of the right “to succeed to the Achaemenid throne” than Darius.

But Alexander’s ultimate choice to set fire to the Achaemenid palace at Persepolis, along with the strong disapproval and resistance of the “whole Persian people,” rendered it impossible for him to pretend to be Darius’ rightful heir. But as Briant notes, Alexander reaffirmed “his claim to legitimacy as the avenger of Darius III” against Bessus (Artaxerxes V).

After it became clear that there was a conspiracy to kill him, one of his officers, Philotas, was put to death for neglecting to warn Alexander. Alexander ordered the assassination of Parmenion, who had been tasked with protecting the treasure at Ecbatana, in order to thwart efforts at retaliation because the son’s death required the father’s death as well. The most notorious incident occurred when Alexander personally killed Cleitus the Black, the man who had saved his life at Granicus, during a violent, inebriated altercation at Maracanda (modern-day Samarkand, Uzbekistan). Cleitus accused Alexander of a number of judgmental errors, most notably that he had abandoned the Macedonian ways in favor of a corrupt oriental lifestyle.

There was another plan for his life that came to light later, during the Central Asian War. His own royal pages were the ones who started this one. In the Anabasis of Alexander, Arrian claims that Callisthenes and the pages were tortured on the rack as punishment and that Callisthenes, his official historian, died shortly after. Callisthenes of Olynthus was implicated in the plan. Since Callisthenes led the resistance to the attempt to impose proskynesis, he had fallen out of favor before his charge, therefore it is still uncertain if he was truly involved in the scheme.

Macedon during Alexander’s absence

Alexander departed for Asia, leaving Macedon under the command of his seasoned commander Antipater, a member of Philip II’s “Old Guard” and a skilled military and political figure. Greece had peace while Alexander was away because of his sacking of Thebes. The lone exception was when Spartan king Agis III called for weapons in 331 BC; Antipater murdered and defeated Agis III in the battle of Megalopolis. Alexander decided to forgive the Spartans when Antipater forwarded the League of Corinth’s penalty to them. Antipater and Olympias also had a great deal of disagreement, and they each complained to Alexander about the other.

Generally speaking, Greece had a time of wealth and tranquility throughout Alexander’s Asian campaign. Large quantities of Alexander’s conquests were returned to him, boosting trade and the economy across his realm. But Macedon’s power was gradually diminished by Alexander’s incessant requests for troops and the migration of Macedonians across his kingdom, which made it much weaker in the years that followed Alexander and finally resulted in Rome’s conquest of Macedon during the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC).

Money

Between 356 and 342 BC, Philip II conquered Pangaeum and subsequently, Thasos, bringing wealthy gold and silver mines under Macedonian rule.

Following the Battle of Issus in 333 BC, Alexander seems to have created a new currency in Cilicia at Tarsus, which eventually became the empire’s primary coinage. Alexander produced a variety of fractional bronze coins, silver tetradrachms and drachims, and gold staters. Throughout his dominion, the designs of these coins never changed. The reverse of the gold series featured a winged Nike (Victory) while the obverse had the head of Athena. The reverse of the silver currency had Zeus aetophoros, or “eagle bearer,” enthroned and holding a scepter in his left hand. The obverse of the coinage featured the bearded head of Heracles with a lionskin headpiece.

This design incorporates both Greek and non-Greek elements. Zeus was the patron of Dium, the principal sanctuary in Macedonia, while Heracles was revered as the progenitor of the Temenid dynasty. Both deities had great significance for the Macedonians. Additionally, the lion served as a sign for Tarsus-worshipped Anatolian god Sandas. Alexander’s tetradrachms’ reverse design is based on a picture of the god Baaltars, also known as Baal of Tarsus, that was found on silver staters that the Persian satrap Mazaeus had produced at Tarsus before to Alexander’s invasion.

Throughout his new conquests, Alexander made no attempt to enforce standardized imperial money. Persian coinage remained in use throughout the empire’s satrapies.

Indian offensive

Incursions onto the Subcontinent of India

Alexander looked to the Indian subcontinent when Spitamenes died and he married Roxana (Raoxshna in Old Persian) to strengthen ties with his new satrapies. He sent an invitation to the chieftains of the erstwhile satrapy of Gandhara, which is currently located near the border between eastern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan, to approach him and submit to his rule. The king of Taxila, Omphis (Ambhi in Indian) whose kingdom stretched from the Indus to the Hydaspes (Jhelum), complied, but some hill clan chieftains, such as those of the Aspasioi and Assakenoi sections of the Kambojas (also called Ashvayanas and Ashvakayanas in Indian texts), refused to submit.

Ambhi hurried to allay Alexander’s fears, presented him with priceless gifts, and offered himself along with all his men.

Ambhi received a wardrobe consisting of “Persian robes, gold and silver ornaments, 30 horses and 1,000 talents in gold” from Alexander in addition to his title and presents. Alexander felt confident enough to divide his army, and Ambhi helped Hephaestion and Perdiccas build a bridge over the Indus where it bends at Hund. He also provided supplies to their troops. Alexander and his entire army were welcomed in Taxila, the capital city, with the utmost friendliness and hospitality.

Taxiles joined the Macedonian monarch on his following offensive with a force of 5,000 soldiers, and they participated in the Battle of the Hydaspes. Following that triumph, Alexander despatched him after Porus, instructing him to make favorable terms. He barely managed to avoid dying at the hands of his longtime foe, though. Alexander personally mediated the reconciliation of the two adversaries; Taxiles assiduously contributed to the fleet’s equipment on the Hydaspes and was given command of the entire region between that river and the Indus.

Following the demise of Philip, son of Machatas, he was bestowed with a significant amount of power, which he continued to hold until Alexander’s death (323 BC), as well as during the division of the provinces at Triparadisus in 321 BC.

Alexander personally oversaw an offensive against the Aspasioi in the Kunar Valley, the Guraeans in the Guraeus Valley, and the Assakenoi in the Swat and Buner Valleys during the winter of 327–326 BC. Alexander was hit in the shoulder by a dart during a heated match between the Aspasioi, but in the end, the Aspasioi were defeated. The Assakenoi then confronted Alexander, engaging them in combat from their strongholds at Massaga, Ora, and Aornos.

After days of brutal battle, during which Alexander suffered a grievous ankle wound, the Massaga fort was diminished. Curtius states that “Not only did Alexander slaughter the entire population of Massaga, but also did he reduce its buildings to rubble.” At Ora, a similar slaughter happened. Many Assakenians took refuge in the stronghold of Aornos after Massaga and Ora. After four deadly days, Alexander closed the gap and took control of the strategically important hill fort.

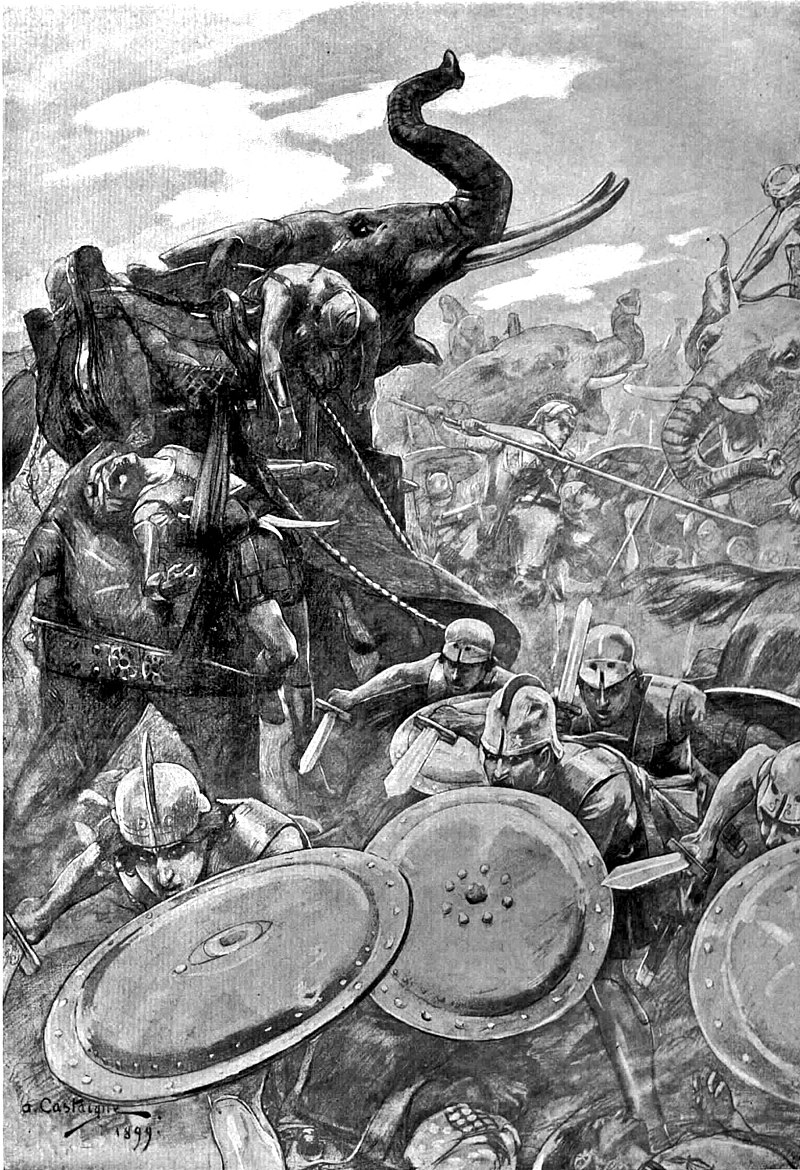

Following Aornos, Alexander crossed the Indus and triumphed in the great Battle of the Hydaspes (326 BC) against King Porus, who governed an area in what is now the Punjab that was between the Hydaspes and the Acesines (Chenab). Porus’s valor won Alexander over, and he became an ally. He made Porus satrap and annexed the area to the southeast, up to the Hyphasis (Beas), that Porus had not previously owned. Selecting a native gave him more authority over these far-off territories from Greece. On different banks of the Hydaspes River, Alexander established two towns, named one Bucephala in memory of his horse, which passed away at this period.

The other was Nicaea (Victory), which is believed to have been situated where Mong, Punjab, is now. In the Life of Apollonius of Tyana, Philostratus the Elder describes how Alexander dedicated the elephant, called Ajax, to the Helios (Sun) after it had fought valiantly against Porus’ army. Alexander felt that such a magnificent creature merited a name of such magnificence. The Greek inscription read, “Alexander the son of Zeus dedicates Ajax to the Helios” (ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΣ Ο ΔIΎΣ ΤΎΝ ΑΙΑΝΤΑ ΤΩΙ ΗΛΙΩΙ), and the elephant’s tusks were ringed with gold.

Army of Greece Revolting

The Indian subcontinent’s Gangaridai Empire and the Nanda Empire of Magadha were located east of Porus’s empire, close to the Ganges River. After years of campaigning, Alexander’s army mutinied at the Hyphasis River (Beas), refusing to march any further east, out of fear of encountering other powerful forces. Thus, this river denotes Alexander’s conquests’ easternmost point.

General Coenus urged Alexander to reconsider and retreat, saying that the troops “longed to see their parents, their wives, and children, their homeland,” despite Alexander’s best efforts to convince them to march deeper. After a while, Alexander consented and marched southward down the Indus. Alexander’s army defeated the Malhi (in present-day Multan) and other Indian tribes en route. However, during the siege of the Malian fortress, an arrow pierced Alexander’s armor and entered his lung, almost killing him.

However, the Macedonians' battle with Porus sapped their bravery and prevented them from moving further with their invasion of India. After exhausting all their options to repel an adversary who managed to muster only 20,000-foot soldiers and 2,000 horse soldiers, they fiercely resisted Alexander's request to cross the Ganges as well. They discovered that the river was thirty-two furlongs (6.4 km) wide, 180 meters deep, and covered in thousands of men-at-arms, horsemen, and elephants on its farther banks. Because they were informed that eighty thousand horsemen, two hundred thousand footmen, eight thousand chariots, and six thousand war elephants were waiting for them at the hands of the rulers of the Ganderites and Praesii.

While Alexander led the remainder of his army back to Persia by the more treacherous southern path across the Gedrosian Desert and Makran, he dispatched a large portion of his army, under General Craterus, to Carmania (modern-day southern Iran). Alexander also commissioned a fleet to investigate the Persian Gulf shore under the command of his Admiral Nearchus. In 324 BC, Alexander made it to Susa, but not before the difficult desert terrain claimed many of his troops.

Persian Years Recently

While traveling to Susa, Alexander discovered that several of his military governors and satraps had misbehaved while he was away. As a result, he beheaded a number of them as examples. In appreciation, he settled his men’s obligations and said that he would return to Macedon with Craterus leading a group of elderly and crippled veterans. At the village of Opis, his soldiers rebelled because they misinterpreted his intentions. They opposed his adoption of Persian attire and traditions, as well as his induction of Persian officers and men into Macedonian formations, and they refused to be sent away.

After three days, Alexander handed Persians command places in the army and gave Persian battalions Macedonian military titles since he was unable to convince his men to give up. Alexander promptly granted the Macedonians’ request for pardon, and he hosted a lavish feast for many thousand of his soldiers. Alexander arranged a mass marriage of his top commanders to Persian and other noblewomen at Susa in an attempt to create a permanent concord between his Macedonian and Persian people, but few of those marriages appear to have lasted much more than a year.

Alexander quickly put an end to the guards who had desecrated Cyrus the Great’s mausoleum at Pasargadae after learning of their actions upon his return to Persia. From a young age, Alexander was inspired by Cyrus the Great after reading Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, which detailed Cyrus’s valor in war and his leadership as a monarch and lawmaker. Alexander gave his architect Aristobulus instructions to adorn Cyrus’s tomb’s sepulchral chamber while he was at Pasargadae.

Alexander then proceeded to Ecbatana in order to recover the most of the Persian loot. Hephaestion, his closest buddy, passed away there from disease or poisoning. Alexander was heartbroken by Hephaestion’s passing and ordered that an elaborate funeral pyre be built in Babylon along with a proclamation of public sorrow. Alexander returned to Babylon and prepared a number of new missions, the first of which would be an invasion of Arabia. However, he would not live to see these through, since he passed not soon after Hephaestion.

To commemorate the conclusion of the Indian War and the start of the Arabian Peninsula invasion, Alexander threw a dinner for his men on May 29. It’s customary for them to begin drinking in earnest only after everyone had finished their meals, but the wine was typically fairly diluted.

Death and the Succession

When someone asked Alexander before he passed away who would take over as his chosen heir in his absence, he replied, “To the strongest one.” It’s possible that he also mentioned that games would be played during his burial.

Alexander passed away at the age of 32 in Nebuchadnezzar II’s palace in Babylon on either June 10 or June 11, 323 BC. There are two accounts of Alexander’s demise, with minor details changing between them. According to Plutarch, Alexander hosted Admiral Nearchus and spent the night and the next day drinking with Medius of Larissa around 14 days before to his death. Alexander started to feel feverish and eventually lost his ability to talk. He waved discreetly to the ordinary troops, who, fearing for their health, were allowed to file past him.

In the second story, Diodorus describes how Alexander, having consumed a big bowl of undiluted wine in honor of Heracles, was hit with anguish and became feeble for eleven days; he did not get feverish but rather passed away after enduring considerable misery. This was another option that Arrian brought forward, although Plutarch expressly refuted it.

Considering the Macedonian nobility’s penchant for assassinations, several versions of his demise suggested foul play. Justin, Arrian, Plutarch, and Diodorus all brought up the possibility that Alexander had been poisoned. Plutarch rejected Justin’s claim that Alexander was the victim of a poisoning plot, while Diodorus and Arrian pointed out that they included the claim just for the sake of being thorough. Despite this, the narratives generally agreed that Craterus, who had just taken over as viceroy of Macedonia from Antipater, was the mastermind behind the supposed conspiracy. Having witnessed the demise of Parmenion and Philotas, and maybe viewing his call to Babylon as a death sentence, Antipater allegedly set up Alexander’s wine-pourer, Iollas, to be poisoned.

It was even suggested that Aristotle could have taken part. The fact that twelve days elapsed between the onset of his illness and his death provides the clearest refutation of the poison theory—such long-acting poisons were most likely unavailable. On the other hand, Leo Schep of the New Zealand National Poisons Centre said in a 2003 BBC program that Alexander’s death may have been caused by the ancient plant known as white hellebore (Veratrum album). In a 2014 paper published in the journal Clinical Toxicology, Schep proposed that Alexander’s wine had been tainted with veratrum album, which would result in poisoning symptoms that corresponded with the plot of the Alexander Romance.

Veratrum album poisoning can take a long time to manifest, and if Alexander was ill, this seems to be the most likely culprit. A different theory of poisoning that surfaced in 2010 suggested that the man’s death was related to water poisoning from the Styx (now Mavroneri in Arcadia, Greece), which contained the toxic substance calicheamicin, which is generated by bacteria.

There have been other natural causes (diseases) proposed, such as typhoid fever and malaria. According to a 1998 New England Journal of Medicine report, he died from typhoid fever that was made worse by ascending paralysis and intestinal perforation. Meningitis or pyogenic (infectious) spondylitis were recommended by a 2004 study. The symptoms can also be found in other conditions such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, West Nile virus, and acute pancreatitis. Natural-cause hypotheses also frequently highlight the possibility that Alexander’s health was generally deteriorating as a result of years of binge drinking and serious injuries. Alexander’s deteriorating health could have also been influenced by the agony he experienced following Hephaestion’s passing.

Occurrences that Follow Death

Alexander’s body was put in a honey-filled gold anthropoid sarcophagus, which was housed inside a gold coffin. Aelian says that a seer by the name of Aristander predicted that the place Alexander was buried “would be happy and unvanquishable forever”. It is possible that the successors viewed the body as a sign of legitimacy because it was their regal right to bury the previous monarch.

Ptolemy grabbed Alexander’s funeral cortege and temporarily transported it to Memphis when it was its route to Macedon. The sarcophagus was moved to Alexandria by his successor, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, and stayed there at least until late antiquity. Alexander’s tomb was replaced with a glass one by Ptolemy IX Lathyros, one of Ptolemy’s last heirs, so he could turn the original into money. Alexander the Great’s massive tomb from Amphipolis, northern Greece, which was discovered in 2014, has sparked conjecture that Alexander was originally intended to be buried there. This would be appropriate given Alexander’s funeral cortege’s intended destination. Nevertheless, it was discovered that the memorial was erected in honor of Alexander the Great’s closest friend, Hephaestion.

Pompey, Julius Caesar, and Augustus all went to the mausoleum at Alexandria where it is said that Augustus knocked off his nose by mistake. Alexander’s armor was allegedly removed by Caligula from the grave for his personal use. Alexander’s tomb was sealed off to the public by Emperor Septimius Severus about the year 200 AD. During his own reign, his great admirer and son Caracalla paid a visit to the grave. What happened to the tomb after this is unclear.

The “Alexander Sarcophagus” was found close to Sidon and is currently housed in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. It was named because of the bas-reliefs that show Alexander and his friends hunting and defeating the Persians, not because it was believed to have Alexander’s bones. Initially, it was believed to be the sarcophagus of Abdalonymus (311–311 BC), the Sidonian ruler Alexander had chosen just after the 331 battle of Issus. Karl Schefold, however, proposed in 1969 that it could have been created before to Abdalonymus’s death.

Demades compared the movements of the Macedonian army following Alexander’s death to those of a blinded Cyclops because of how haphazard and disorganized it was. Moreover, Leosthenes compared the chaos among the generals following Alexander’s demise to that of the blind Cyclops, “who after he had lost his eye went feeling and groping about with his hands before him, not knowing where to lay them”.