Introduction to Afghanistan

At the meeting point of Central and South Asia, Afghanistan, formally known as the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked nation. Pakistan borders it on the east and south; Iran borders it on the west; Turkmenistan borders it on the northwest; Tajikistan borders it on the northeast; Uzbekistan borders it on the north; and China borders it on the northeast and east.

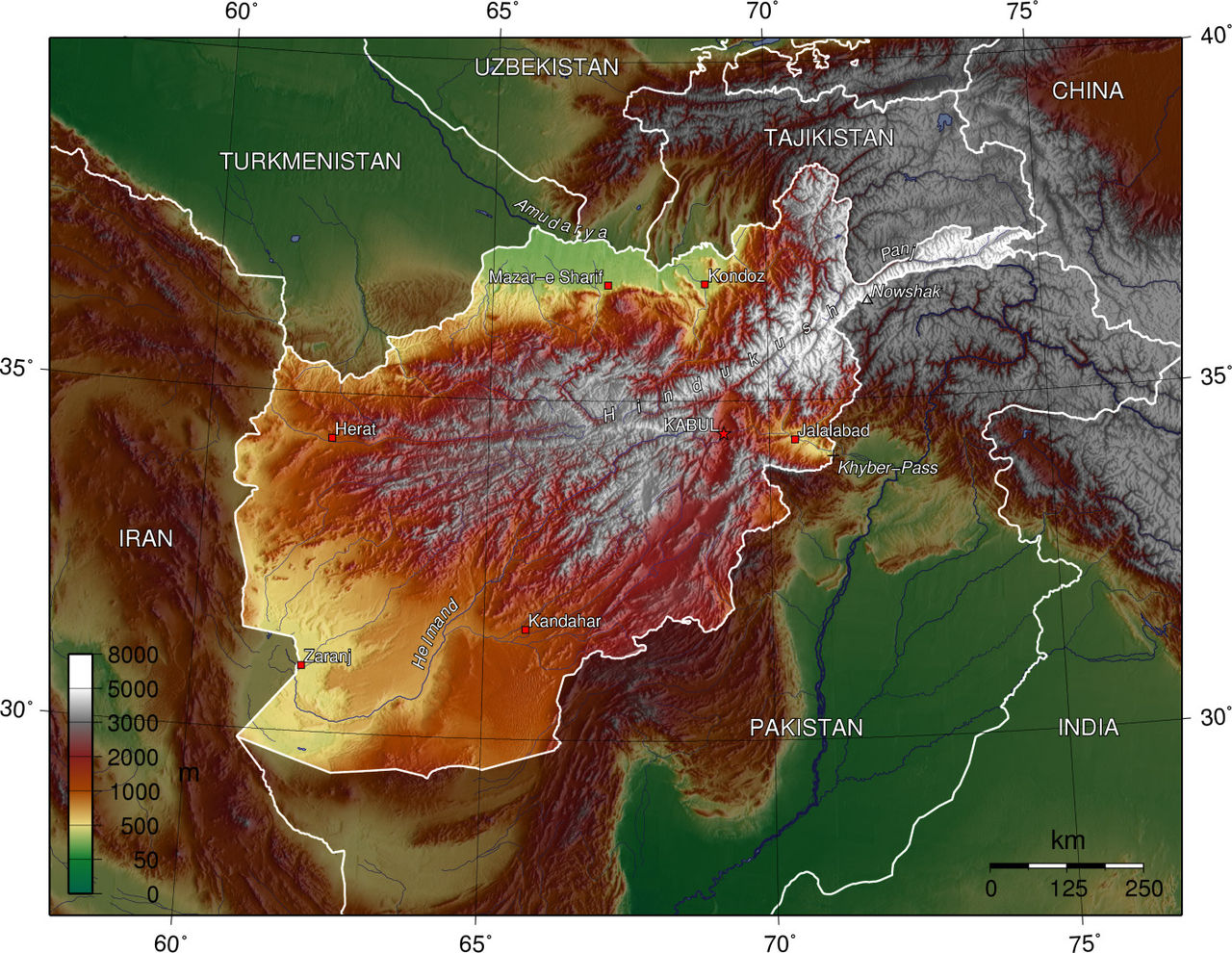

The nation, which has 652,864 square kilometers (252,072 sq mi) of territory, is primarily mountainous, with plains located in the north and southwest and divided by the Hindu Kush mountain range.

The largest city and capital of the nation is Kabul. Afghanistan has 43 million people living there as of 2023, according to the World Population Review. In 2020, the population of Afghanistan was projected by the National Statistics Information Authority to reach 32.9 million.

Afghanistan has been inhabited by humans since the Middle Paleolithic. Known as the “graveyard of empires,” the region has seen several military operations, including those led by the US-led coalition, the Maurya Empire, the Persians, Alexander the Great, Arab Muslims, and the Mongols.

Afghanistan was also the cradle of large empires formed by the Mughals, the Greco-Bactrians, and other groups. The region was a hub for Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and eventually Islam due to the numerous conquests and eras in both the Iranian and Indian cultural domains.

While Dost Mohammad Khan is occasionally cited as the first modern Afghan state’s creator, the Durrani Afghan Empire founded the modern state of Afghanistan in the 18th century. Afghanistan developed and became a bulwark in the Great Game between the Russian and British Empires.

In the First Anglo-Afghan War, the British tried to conquer Afghanistan from India but were defeated; in the Second Anglo-Afghan War, the British won. Afghanistan was freed from foreign political dominion during the

Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919, and it became the sovereign Kingdom of Afghanistan in 1926. This monarchy lasted for over fifty years until the fall of Zahir Shah in 1973, at which point the Republic of Afghanistan was founded.

Afghanistan’s history has been characterized by protracted conflict, including civil wars, invasions, coups, and insurgencies, since the late 1970s. After a communist revolution created a socialist state in 1978, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979 as a result of internal strife.

During the Soviet-Afghan War, the Mujahideen battled the Soviet Union; when the Soviet Union withdrew in 1989, they continued to fight one another. By 1996, the Taliban held sway over much of the nation, but prior to the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, its Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan garnered less international recognition. When the Taliban took control of Kabul in 2021, the conflict that lasted from 2001 to 2021 came to a conclusion. The Taliban administration is still not acknowledged worldwide.

Natural resources abound in Afghanistan, including copper, iron, zinc, and lithium. It is the third-biggest producer of cashmere and saffron, and the second-biggest producer of cannabis resin. The nation is a founding member of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and a member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation.

The nation has struggled with high levels of terrorism, poverty, and child malnutrition as a result of the consequences of conflict in recent decades. Afghanistan, which is ranked 180th in the Human Development Index, is still one of the least developed nations in the world. By purchasing power parity, Afghanistan’s GDP is $81 billion, whereas nominal values place it at $20.1 billion. As of 2020, its GDP per capita is among the lowest of any nation.

Meaning and Origin

According to some experts, the Sanskrit word Aśvakan, which was once used to refer to the ancient people of the Hindu Kush, is where the root name Afghān originates. The phrase “horsemen,” “horse breeders,” or “cavalrymen” is literally translated as “aśvakan” (from the Sanskrit and Avestan roots for “horse”).

Traditionally, ethnic Pashtuns were referred to as Afghān. Hudud al-‘Alam, a geography book from the 10th century, is the first source mentioning the term Afġān in Arabic and Persian. “-stan,” the name’s last component, is a Persian suffix that means “place of.” Consequently, historically speaking, “Afghanistan” means “land of the Afghans” or “land of the Pashtuns”. As stated in the Encyclopedia of Islam, Third Edition:

Afghanistan (Afghānistān, land of the Afghans / Pashtuns, afāghina, sing. afghān) was named for the easternmost region of the Kartid dominion in the early eighth or early fourteenth century. Later, this term was used to several Afghan-inhabited areas under the Ṣafavid and Mughal empires. Even though it was founded on an elite of Abdālī / Durrānī Afghans who supported the state, the Sadūzā\ī Durrānī polity, which emerged in 1160 / 1747, was not known as Afghanistan in its own time. It wasn't until the nineteenth-century colonial interference that the name was designated as a state.

When the British acknowledged Dost Mohammad Khan as king of Afghanistan in 1855, the name “Afghanistan” was first used in an official capacity.

Past Events

Ancient times and prehistory

Prehistoric site excavations indicate that farming societies in the region were among the first in the globe and that humans were residing in what is now Afghanistan at least 50,000 years ago. Afghanistan is a significant location for early historical activity, and many people think that the historical significance of its archeological monuments is comparable to that of Egypt.

Afghanistan has produced artifacts from the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron Ages. It is thought that urban civilization dates back to 3000 BCE. The Helmand culture was centered at the early city of Mundigak, which was located near Kandahar in the southern part of the nation. Recent discoveries have confirmed that the Indus Valley Civilization extended as far as present-day Afghanistan.

On the Oxus River near Shortugai in northern Afghanistan, an Indus Valley site has been discovered.

Following 2000 BCE, waves of semi-nomadic people from Central Asia started migrating southward into Afghanistan; many of them were Indo-Iranians, who spoke Indo-European. Later, these tribes moved across the region north of the Caspian Sea and into Western Asia, South Asia, and eventually toward Europe.

At the time, the area was known as Ariana. The Achaemenids defeated the Medes by the middle of the sixth century BCE, and they included Arachosia, Aria, and Bactria under their control. The Kabul Valley is included among the 29 nations that Darius I of Persia had subjugated in an inscription on his monument.

Some refer to the area that was formerly mostly Zoroastrian—the Arachosia region, which is now in southern Afghanistan—as the “second homeland of Zoroastrianism” since it was crucial in the Avesta’s translation to Persia.

A year after taking down Darius III of Persia at the Battle of Gaugamela, Alexander the Great and his Macedonian army landed in Afghanistan in 330 BCE. The Seleucid Empire, Alexander’s short-lived successor, ruled the area until 305 BCE when they ceded parts of it to the Maurya Empire as part of an alliance pact.

The region south of the Hindu Kush was ruled by the Mauryans until they were driven out in around 185 BCE. Sixty years after Ashoka’s authority ended, they started to collapse, which allowed the Greco-Bactrians to reconquer Hellenistic territory. A large portion of it quickly separated and joined the Indo-Greek Kingdom. In the latter part of the second century BCE, the Indo-Scythians routed and drove them out.

The Parthian Empire conquered the area in the first century BCE, but its Indo-Parthian vassals eventually overthrew them. The enormous Kushan Empire, which was based in Afghanistan, became a major benefactors of Buddhist culture in the middle to late first century CE, causing Buddhism to thrive throughout the area.

The Indo-Sassanids ruled at least some of the region after the Sassanids toppled the Kushans in the third century CE. The Kidarites came after them, and the Hephthalites took their position after them.

In the seventh century, the Turk Shahi took their place. Before the Saffarids took over the region in 870, the Buddhist Turk Shahi of Kabul was succeeded by a Hindu dynasty known as Hindu Shahi.

Buddhism continued to be the predominant religion in a large portion of the country’s northeast and south.

The Middle Ages

In 642 CE, Arab Muslims introduced Islam to Herat and Zaranj and started to move eastward; some local populations they came across embraced it, while others rose up in rebellion. The area was home to a variety of cults and beliefs before to the introduction of Islam, which frequently led to syncretism amongst the main religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, or Greco-Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and ancient Iranian religions.

One example of the region’s syncretism would be the worship of Iranian deities such as Ahura Mazda, Lady Nana, Anahita, or Mihr (Mithra) with Buddhist patrons who depicted Greek gods as Buddha’s guardians.

The Saffarid Muslims of Zaranj initially overthrew the Zunbils and Kabul Shahi in 870 CE. Subsequently, the Samanids spread Islam’s sway south of the Hindu Kush. The tenth century saw the rise to dominance of the Ghaznavids.

Mahmud of Ghazni successfully overthrew the last Hindu kings by the eleventh century, bringing Islam to much of the surrounding area—with the exception of Kafiristan. Mahmud elevated Ghazni to a significant metropolis and supported thinkers like poet Ferdowsi and historian Al-Biruni.

The Ghurid dynasty, whose accomplishments in architecture included the distant Minaret of Jam, toppled the Ghaznavid dynasty in 1186. Afghanistan was ruled by the Ghurids for less than a century before the Khwarazmian dynasty took over in 1215.

Genghis Khan and his Mongol army conquered the area in 1219 CE. It is reported that his armies destroyed Bamyan and the Khwarazmi towns of Herat and Balkh. Many of the residents were compelled to revert to an agricultural rural culture as a result of the Mongols’ damage.

The Ilkhanate in the northwest was the center of Mongol control, while the Khalji dynasty ruled over the tribal regions of Afghanistan south of the Hindu Kush until Timur (also known as Tamerlane) invaded and founded the Timurid Empire in 1370. Under Shah Rukh’s leadership, the city of Herat functioned as the hub of the Timurid Renaissance, an Italian Renaissance movement whose magnificence rivaled Florence.

Babur arrived from Ferghana at the beginning of the 16th century and took control of Kabul from the Arghun dynasty. The Afghan Lodi dynasty, which had dominated the Delhi Sultanate in the First Battle of Panipat, would later be subjugated by Babur.

Parts of the region were administered by the Indian Mughals, the Safavids of Iran, and the Uzbek Khanate of Bukhara during the 16th and the 18th centuries. The northwest region of Afghanistan was known by the regional name Khorasan throughout the medieval era. Native Americans continued to use this term to refer to their homeland until the 19th century.

The Hotak Dynasty

Local Ghilzai tribal chieftain Mirwais Hotak staged a victorious rebellion against the Safavids in 1709. He overthrew Gurgin Khan, the Safavid administrator of Georgia in Kandahar, and founded his own country. After Mirwais passed away in 1715, his brother Abdul Aziz took over as ruler.

However, Mahmud, Mirwais’s son, assassinated Abdul Aziz shortly afterward for allegedly plotting to make peace with the Safavids. Following the Battle of Gulnabad, Mahmud led the Afghan army to the Persian capital of Isfahan in 1722, where he declared himself King of Persia and took control of the city. Following the Battle of Damghan in 1729, Nader Shah drove the Afghan dynasty out of Persia.

The final Hotak stronghold, Kandahar, was taken from Shah Hussain Hotak in 1738 by Nader Shah and his army. The Persian and Afghan armies attacked India shortly after, and Nader Shah, accompanied by his 16-year-old commander Ahmad Shah Durrani, who had aided him in past operations, pillaged Delhi. In 1747, Nader Shah was murdered.

Empire of Durrani

Ahmad Shah Durrani had returned to Kandahar with 4,000 Pashtuns following the death of Nader Shah in 1747. Ahmad Shah had been “unanimously accepted” as the new leader of the Abdalis. Ahmad Shah had led several campaigns against the Mughal Empire, the Maratha kingdom, and the Afsharid dynasty, which was then in decline, since his succession in 1747.

Ahmad Shah had overthrown Nasir Khan, the administrator chosen by the Mughals, and taken Peshawar and Kabul. After that, in 1750, Ahmad Shah took control of Herat, and in 1752, he also took control of Kashmir.

Two expeditions into Khorasan were conducted by Ahmad Shah in 1750–1751 and 1754–1755. The siege of Mashhad had been part of his first campaign, but after four months he was compelled to withdraw.

He marched to lay siege to Nishapur in November 1750 but was unable to take the city and had to withdraw in the early months of 1751. When Ahmad Shah arrived in 1754, he took Tun prisoner and again besieged Mashhad on July 23. On December 2, Mashhad fell, but in 1755, Shahrokh was appointed again. He was compelled to acknowledge Afghan sovereignty and cede to the Afghans Torshiz, Bakharz, Jam, Khaf, and Turbat-e Haidari. Ahmad Shah then laid siege to Nishapur once more and took it.

During his reign, Ahmad Shah invaded India eight times, starting in 1748. His forces crossed the Indus River, ransacked Lahore, and incorporated it into the Durrani Realm. At the Battle of Manupur (1748), he faced Mughal soldiers and was ultimately defeated, being forced to escape back to Afghanistan.

He made a comeback the next year, in 1749, and claimed success for the Afghans in this battle by capturing the region surrounding Lahore and Punjab. Ahmad Shah conducted six further invasions between 1749 and 1767, the most significant of which was the last one, the Third Battle of Panipat, which ended Maratha’s progress by creating a power vacuum in northern India.

Following the death of Ahmad Shah Durrani in October 1772, there was a civil war for succession, with Timur Shah Durrani, who had been selected as his heir, taking power when his brother Suleiman Mirza was defeated. In November 1772, Timur Shah Durrani became the emperor after vanquishing a coalition led by Humayun Mirza and Shah Wali Khan.

In order to establish his authority and unite his supporters, Timur Shah eliminated the Durrani Sardars and powerful tribal chiefs from Kabul and Kandahar at the start of his rule. The Durrani Empire’s capital was moved from Kandahar to Kabul as one of Timur Shah’s reforms. In addition to leading, albeit more effectively than his father, expeditions into Punjab against the Sikhs, Timur Shah put down several series of rebellions in order to establish the empire.

During this war, the most notable of his fights was when he led his soldiers under Zangi Khan Durrani against over 60,000 Sikh men, totaling over 18,000 Afghan, Qizilbash, and Mongol cavalrymen. In this fight, the Sikhs suffered over 30,000 casualties and launched a Durrani uprising in the Punjab area.

Following Ahmad Shah’s death in 1772, the Durranis lost Multan. After this triumph, Timur Shah was able to besiege and retake Multan, reuniting it as a province until the Siege of Multan (1818) and reinstating it into the Durrani Empire. After Timur Shah passed away in May 1793, his son Zaman Shah Durrani took over as ruler. During Timur Shah’s rule, the empire was sought to be stabilized and consolidated.

Timur Shah, however, had more than 24 sons, which led to a civil war in the empire due to issues with succession.

After Timur Shah Durrani, his father, passed away, Zaman Shah Durrani assumed the Durrani Throne. Humayun Mirza and Mahmud Shah Durrani, his brothers, rose up in rebellion against him; Humayun’s base was in Kandahar, while Mahmud Shah’s was in Herat.

Mahmud Shah Durrani’s allegiance would be forced by Zaman Shah’s victory against Humayun. Leading three campaigns into Punjab, Zaman Shah solidified his place on the throne.

Lahore was taken during the first two assaults, but he withdrew after receiving intelligence about a potential Qajar attack. In 1800, Zaman Shah launched his third campaign for Punjab in response to a dissident Ranjit Singh. But Mahmud Shah Durrani pushed him to retreat, and Zaman Shah’s rule came to an end.

But on July 13, 1803, a little under two years into his rule, Mahmud Shah Durrani was overthrown by his brother, Shah Shuja Durrani. At the Battle of Nimla (1809), Shah Shuja was overthrown by his brother despite his attempts to unite the Durrani Realm. Shah Shuja was vanquished by Mahmud Shah Durrani, who then took the throne for himself. On May 3, 1809, his second reign got underway.

British Warfare and the Barakzai Dynasty

The Afghan Empire faced threats from the Persians in the west and the Sikh Empire in the east by the early 1800s. The Barakzai tribe’s chief, Fateh Khan, put several of his brothers in positions of authority across the realm.

Mahmud Shah mercilessly killed Fateh Khan in 1818. A civil war ensued as a result of the rebellion of the Barakzai clan and the brothers of Fateh Khan. The Principality of Qandahar, Emirate of Herat, Khanate of Qunduz, Maimana Khanate, and several more warring polities were among the several governments that emerged from Afghanistan during this volatile time. Dost Mohammad Khan’s Emirate of Kabul was the most well-known state.

After the Durrani Empire fell and the Sadozai Dynasty was sent into exile and left to govern in Herat, Punjab, and Kashmir fell to the Sikh Empire’s Ranjit Singh. In March 1823, Singh invaded Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and took Peshawar after the Battle of Nowshera.

Dost Mohammad Khan launched many expeditions in 1834. He initially went to Jalalabad and then formed an alliance with his rival brothers in Kandahar to oppose the British in the Shuja ul-Mulk expedition headed by Shah Shuja Durrani. The Battle of Jamrud resulted from Dost Mohammad Khan’s effort to subjugate Peshawar in 1837 when he dispatched a sizable army under his son Wazir Akbar Khan.

The Afghan-Sikh Wars came to an end when Akbar Khan and the Afghan army murdered Sikh Commander Hari Singh Nalwa, although they were unable to take the Jamrud Fort from the Sikh Khalsa Army. By now the British were moving eastward, taking advantage of the Sikh Empire’s collapse following Ranjit Singh’s death, which had caused the Emirate of Kabul to get embroiled in the first significant battle of “The Great Game”.

A British invasion army entered Afghanistan in 1839, conquered the Principality of Qandahar, and took control of Kabul in August of the same year. In the Parwan campaign, Dost Mohammad Khan routed the British, only to turn tail and surrender. As the new de facto puppet of the British, he was succeeded as the ruler of Kabul by the old Durrani king, Shah Shuja Durrani.

The British gave up trying to conquer Afghanistan after an uprising that resulted in the assassination of Shah Shuja, the British-Indian forces’ withdrawal from Kabul in 1842 and the destruction of Elphinstone’s army, and the punitive expedition of The Battle of Kabul, which led to its sacking. Dost Mohammad Khan then reestablished his rule over the country.

After this, Dost Mohammad launched a plethora of operations to unify much of Afghanistan under his rule, including many assaults on neighboring nations, including the campaigns of Hazarajat, Balkh, Kunduz, and Kandahar.

Dost Mohammad oversaw his last assault against Herat, bringing Afghanistan back together in the process. In the midst of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, Bukhara and domestic religious leaders put pressure on Dost Muhammad to invade India, but during his campaigns of reunification, he maintained cordial relations with the British despite the First Anglo-Afghan War and confirmed their status in the Second Anglo-Afghan Treaty of 1857.

In June 1863, Dost Muhammad passed away, just a few weeks following his victorious expedition to Herat. A civil war broke out between his sons after his death, with Sher Ali Khan, Mohammad Azam Khan, and Mohammad Afzal Khan leading the charge.

Following his victory in the Afghan Civil War (1863–1869), Sher Ali governed Afghanistan until his passing in 1879. In the Second Anglo-Afghan War, fought during his dying years, the British returned to Afghanistan to counter projected Russian dominance in the area. With the intention of establishing a resistance there like to that of his predecessors, Dost Mohammad Khan and Wazir Akbar Khan, Sher Ali withdrew to northern Afghanistan.

After his sudden death, however, Yaqub Khan was proclaimed the new Amir, and as a result, Afghanistan became an official British Protected State and Britain gained control over its foreign policy by the 1879 Treaty of Gandamak. But an insurrection reignited the fighting, leading to Yaqub Khan’s overthrow.

During this turbulent time, Abdur Rahman Khan started to gain influence and, after seizing control of most of Northern Afghanistan, became eligible to run for the position of Amir. After marching into Kabul, Abdur Rahman was crowned Amir and received British recognition. Ayub Khan challenged the British again, and at the Battle of Maiwand, rebels faced and overcame British soldiers.

After his triumph, Ayub Khan attempted to besiege Kandahar but was ultimately defeated; as a result, the Second Anglo-Afghan War came to a conclusion and Abdur Rahman was securely established as the Amir. Abdur Rahman signed an agreement in 1893 that split the ethnic Pashtun and Baloch lands along the Durand Line, which now serves as Pakistan’s and Afghanistan’s contemporary border.

Political independence was maintained by the Shia-dominated Hazarajat and the pagan Kafiristan until they were overrun by Abdur Rahman Khan in 1891–1896, respectively. Because of his appearance and his merciless tactics against tribes, he was referred to as the “Iron Amir”. Habibullah Khan, his son, succeeded him after his death in 1901.

Afghanistan is a little power, like a grain of wheat between two powerful millstones in a grinding mill, or a goat between these lions (Britain and Russia). How can it stand in the middle of the stones without being crushed to dust?

— “Iron Amir” Abdul Rahman Khan, about 1900

In the Niedermayer-Hentig Expedition, Habibullah Khan was greeted by representatives of the central powers during the First World War, when Afghanistan remained neutral. As part of the Hindu-German Conspiracy, they demanded that Afghanistan formally separate from the United Kingdom, band up with them, and launch an assault on British India.

Although the attempt to include Afghanistan in the Central Powers was unsuccessful, it caused unrest among the populace over their continued neutrality against the British. Following Habibullah’s murder in February 1919, Amanullah Khan came to be in charge. Amanullah Khan, who entered British India through the Khyber Pass, started the Third Anglo-Afghan War by invading the country and was a fervent supporter of the 1915–1916 missions.

Emir Amanullah Khan proclaimed the Emirate of Afghanistan a sovereign and completely independent state following the conclusion of the Third Anglo-Afghan War and the signing of the Treaty of Rawalpindi on August 19, 1919.

He took steps to break his nation’s historical isolation by forging diplomatic ties with other nations, especially the Soviet Union and the Weimar Republic. On June 9, 1926, he declared himself the King of Afghanistan, creating the Kingdom of Afghanistan.

He enacted a number of changes aimed at modernizing his country. Strongly advocating for women’s education, Mahmud Tarzi was a driving force behind these reforms. He campaigned for Afghanistan’s 1923 constitution’s Article 68, which mandated primary education. In 1923, slavery was outlawed.

During this time, Queen Soraya, the spouse of King Amanullah, played a significant role in the struggle for women’s education and against their subjugation.

Many tribal and religious leaders were offended by some of the changes, which included establishing coeducational schools and doing away with the customary veil for women. This animosity sparked the Afghan Civil War (1928–1929).

After King Amanullah abdicated in January 1929, Kabul was overrun by Habibullah Kalakani’s Saqqawist soldiers. After defeating and killing Kalakani in October 1929, Mohammed Nadir Shah, Amanullah’s cousin, was crowned King Nadir Shah. He eschewed King Amanullah’s policies in favor of a more measured modernization strategy, but Abdul Khaliq killed him in 1933.

After his accession to the throne, Mohammed Zahir Shah ruled as king from 1933 to 1973. King Zahir’s rule was challenged during the 1944–1947 tribal uprisings by tribesmen from the Zadran, Safi, Mangal, and Wazir groups, many of whom were loyalists to Amanullah and headed by Mazrak Zadran, Salemai, and Mirzali Khan. In 1934, Afghanistan acceded to the League of Nations.

The 1930s brought with it the construction of infrastructure, roads, a national bank, and higher education. An expanding cotton and textile sector was largely fueled by road connections in the north. The nation forged strong ties with the Axis powers, with Nazi Germany contributing the most to the growth of Afghanistan during that period.

With the help of his uncle, who served as prime minister and carried on Nadir Shah’s policies, King Zahir reigned until 1946. When Shah Mahmud Khan, another uncle, took over as prime minister in 1946, he experimented with granting more political freedom.

After Mohammed Daoud Khan, a Pashtun nationalist who favored the establishment of a Pashtunistan, succeeded him in 1953, ties with Pakistan became extremely strained. Daoud Khan pushed for changes in social modernization and a stronger alliance with the Soviet Union. Following this, the 1964 constitution was drafted and the first prime minister who was not royal was sworn in.

Similar to his father Nadir Shah, Zahir Shah pursued national independence preservation along with progressive modernization, nationalist sentiment building, and better ties with the United Kingdom.

Afghanistan did not take part in the Second World War or support any of the major Cold War powers. However, it benefited from the later rivalry as the US and the USSR competed for dominance by constructing Afghanistan’s key thoroughfares, airports, and other infrastructure.

Afghanistan was the recipient of more Soviet development aid per person than any other nation. The monarchy was overthrown in 1973 when Daoud Khan, acting as the country’s first president, staged a bloodless coup while the King was visiting Italy.

War between the Soviet Union and the Democratic Republic

In what is known as the Saur Revolution, the communist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) overthrew then-President Mohammed Daoud Khan in a violent coup d’état in April 1978. The People’s Democratic Party General Secretary Nur Muhammad Taraki was selected as the first leader of the newly proclaimed Democratic Republic of Afghanistan by the PDPA.

This would set off a chain of events that would drastically transform Afghanistan from a peaceful, impoverished nation into a hub for international terrorism. The PDPA mercilessly suppressed political dissidents while enacting a number of social, symbolic, and land distribution changes that met with fierce resistance.

This led to instability, which by 1979 had swiftly escalated into a civil war fought across the nation by guerilla mujahideen and smaller Maoist insurgents against government troops. With the help of these rebels’ secret training facilities from the Pakistani government, hundreds of military advisors from the Soviet Union, and US assistance from Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the conflict swiftly devolved into a proxy war. In the meantime, tensions between the opposing PDPA factions—the more moderate Parcham and the powerful Khalq—were growing more antagonistic.

Hafizullah Amin, the prime minister at the time, planned an internal coup in which PDPA general secretary Taraki was killed in October 1979. Amin went on to become the new general secretary of the People’s Democratic Party.

Under Amin, the nation’s circumstances worsened and thousands of people vanished. In December 1979, the Soviet Army invaded the nation because they were unhappy with Amin’s regime. They planned to execute Amin by going to Kabul.

The void was filled by a Soviet-run government that included both the Parcham and Khalq groups and was headed by Babrak Karmal of Parcham. The Soviet-Afghan War began when larger contingents of Soviet forces were sent to pacify Afghanistan under Karmal.

Over the course of the nine-year conflict, between 562,000 and 2 million Afghans lost their lives and around 6 million were forced to flee their country, primarily to Pakistan and Iran. Millions of landmines were placed, several rural villages were devastated by heavy air bombardment, and certain towns, including Herat and Kandahar, suffered damage as a result of the shelling. Following the Soviet withdrawal, there was a civil war, which lasted until 1992, when the communist government led by Mohammad Najibullah of the People’s Democratic Party fell.

Afghanistan’s society was drastically impacted by the Soviet-Afghan War. Due to the country’s increasing militarization, highly armed police, private bodyguards, openly armed civic defense organizations, and other similar practices were commonplace in Afghanistan for many years to come. Strong warlords had replaced the military, religion, community leaders, and intellectuals as the traditional power structure.

Conflict following the Cold War

Following the formation of an ineffective coalition government by leaders of several mujahideen factions, another civil war broke out. While Kabul was brutally battered and nearly destroyed by the war, different mujahideen factions perpetrated widespread acts of rape, murder, and extortion in a state of lawlessness and factional infighting.

There were other instances of failed alliances and reconciliations between various leaders. In September 1994, a group of students from Pakistani Islamic madrassas (schools) called the Taliban came into being as a militia and organization.

Pakistan quickly provided them with military backing. After seizing control of Kandahar City in the same year, they continued to annex additional land until, in 1996, they succeeded in forcing the Rabbani administration from Kabul, where they created an emirate.

The Taliban faced worldwide censure due to their strict adherence to their interpretation of Islamic sharia law, which led to the violent mistreatment of several Afghans, particularly women.

The Taliban and its supporters carried out a campaign of scorched earth, burning large tracts of agricultural land and demolishing tens of thousands of homes while in power. They also massacred Afghan people and refused UN food deliveries to hungry civilians.

Ahmad Shah Massoud and Abdul Rashid Dostum established the Northern Alliance, which was eventually joined by others, to oppose the Taliban when the latter took control of Kabul. Following the Taliban’s victories over Dostum’s forces in the Mazar-i-Sharif battles of 1997 and 1998, Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff, Pervez Musharraf, started sent hundreds of Pakistanis to aid the Taliban in their fight against the Northern Alliance.

Just 10% of the region was under Northern Alliance control in 2000, with its northeast cornered. In the Panjshir Valley on September 9, 2001, two Arab suicide terrorists killed Massoud. Between 1990 and 2001, domestic strife claimed the lives of almost 400,000 Afghans.

US-led assault and Islamic Republic

After the Taliban refused to turn up Osama bin Laden, the main suspect in the September 11 attacks, who was a “guest” of the Taliban and running his al-Qaeda network in Afghanistan, the United States invaded the country in October 2001 in order to overthrow the Taliban. Most Afghans were in favor of the US intervention. US and UK soldiers struck al-Qaeda training centers during the first invasion and later collaborated with the Northern Alliance to overthrow the Taliban rule.

Following the toppling of the Taliban regime, Hamid Karzai established the Afghan Interim Administration in December 2001. The UN Security Council created the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to support the Karzai government and offer fundamental security.

Afghanistan had one of the highest newborn and child mortality rates in the world, the lowest life expectancy, a large number of hungry people, and severely damaged infrastructure by this point, following two decades of conflict and a severe famine at the time. Numerous international donors began contributing to the reconstruction of the nation devastated by conflict.

The Taliban launched an insurgency to retake power when coalition forces invaded Afghanistan to aid in the reconstruction effort. Due to the Taliban insurgency, a lack of foreign investment, and government corruption, Afghanistan continues to rank among the world’s poorest nations.

The Islamic Republic of Afghanistan adopted a new constitution in 2004 after the Afghan government was able to establish several democratic institutions. Efforts were undertaken to enhance the nation’s transportation, agriculture, healthcare, education, and economy, sometimes with the backing of outside donor nations.

The Afghan National Security personnel were also put through training by ISAF personnel. Almost five million Afghans were returned after 2002. NATO forces in Afghanistan reached a peak of 140,000 in 2011 and decreased to around 16,000 in 2018.

Following the 2014 presidential election, which saw the democratic transfer of power for the first time in Afghanistan’s history, Ashraf Ghani was sworn in as president in September. NATO fully concluded ISAF combat operations on December 28, 2014, and gave the Afghan government complete control over security matters.

On the same day that ISAF was constituted, the NATO-led Operation Resolute Support was established. Thousands of NATO soldiers stayed behind to support and mentor Afghan government forces as they pursued their conflict with the Taliban. A study named “Body Count” came to the conclusion that all sides in the conflict had murdered between 106,000 and 170,000 civilians in Afghanistan.

Qatar hosted the US-Taliban meeting on February 19, 2020. The agreement was one of the key factors that led to the fall of the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF); after it was signed, the US drastically cut back on airstrikes and denied the ANSF a vital advantage in quelling the Taliban insurgency, which allowed the Taliban to seize control of Kabul.

The Taliban’s second period

On April 14, 2021, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said that the alliance has decided to begin removing its soldiers from Afghanistan by May 1. The Taliban soon surged in front of crumbling Afghan government forces after launching an attack against the government shortly after NATO soldiers started to depart.

On August 15, 2021, the Taliban retook control of the great majority of Afghanistan and took the capital city of Kabul. Many Afghan citizens attempted to depart alongside the foreign diplomats and Afghan government leaders who were evacuated from the country, including President Ashraf Ghani.

First vice president Amrullah Saleh declared himself caretaker president on August 17 and declared that he and Ahmad Massoud would organize an anti-Taliban front in the Panjshir Valley with about 6,000 troops. But by September 6th, resistance fighters had fled to the mountains as the Taliban had taken over much of Panjshir province. By mid-September, fighting in the valley had stopped.

The Costs of War Project estimates that between 2001 and 2021, the fighting claimed the lives of 176,000 individuals, 46,319 of them were civilians. The Uppsala Conflict Data Program estimates that the conflict claimed the lives of at least 212,191 individuals. Even though the country’s state of war ended in 2021, warfare between the Taliban and the local Islamic State branch, as well as an anti-Taliban Republican insurgency, continue to cause violent conflict in some areas.

Hibatullah Akhundzada, the supreme commander of the Taliban, and Hasan Akhund, the interim prime minister, assumed office on September 7, 2021. One of the four founders of the Taliban, Akhund served as the previous emirate’s deputy prime minister and was chosen as a middle ground between moderates and hardliners.

A new cabinet including only men was created, with Abdul Hakim Haqqani appointed as the minister of justice. The acting minister of foreign affairs, Amir Khan Muttaqi, sent a letter to UN Secretary-General António Guterres on September 20, 2021, formally claiming Afghanistan’s seat as a member state for their official spokesman in Doha, Suhail Shaheen.

The previous Taliban administration was not recognized by the UN, which opted to cooperate with the government in exile at the time.

After the Taliban took control of the country in August 2021, the majority of humanitarian help from Western countries was withdrawn; payments from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund were also discontinued.

In October 2021, about half of Afghanistan’s 39 million inhabitants experienced a severe food scarcity. On November 11, 2021, Human Rights Watch claimed that an economic and financial crisis was causing severe starvation in Afghanistan.

The Taliban, who are now ranked 150th on the corruption monitor perception rating, have made great progress in combating corruption. According to reports, the Taliban have also lessened extortion and bribery in public service sectors. Concurrently, the state of human rights in the nation has declined.

More than 5.7 million refugees left Afghanistan after the invasion of 2001 and returned; nevertheless, as of 2021, 2.6 million Afghans were still refugees, mostly in Iran and Pakistan, and a further 4 million were domestically displaced.

The government of Pakistan issued an order for Afghans to be removed from the country in October 2023. Iran likewise made the decision to send Afghan nationals back to their own country. Taliban officials called the deportations of Afghans a “inhuman act” and denounced them. In late 2023, there was a humanitarian catastrophe in Afghanistan.

Geographical

Situated in Southern-Central Asia lies Afghanistan. Afghanistan, the “crossroads of Asia,” has earned the moniker “Heart of Asia” for the region it centers on. Famous Urdu poet Allama Iqbal once described the nation as follows:

The nation of Afghanistan is the center of Asia, a continent made up of ocean and land. From its disagreement, Asia's disagreement; and from its agreement, Asia's agreement.

Afghanistan, spanning approximately 652,864 km2 (252,072 sq mi), is the 41st biggest nation in the world. It is around the size of Texas in the United States and is somewhat larger than France and smaller than Myanmar.

Afghanistan is landlocked, hence there isn’t any shoreline. India recognizes a border with Afghanistan through Pakistani-administered Kashmir. Afghanistan shares its longest land border (the Durand Line) with Pakistan to the east and south. Its borders are followed by those with Tajikistan to the northeast, Iran to the west, Turkmenistan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, and China to the far northeast.

Afghanistan’s borders are as follows, going clockwise from the southwest: Iran’s Sistan and Baluchestan Province, South Khorasan Province, and Razavi Khorasan Province; Uzbekistan’s Surxondaryo Region; Khatlon Region and Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region of Tajikistan; China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region; and Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan territory, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, and Balochistan province.

Afghanistan’s topography is diverse, although it is primarily harsh and hilly, with several peculiar mountain ranges that are complemented by plateaus and river basins. It is dominated by the Hindu Kush range, which is the western extension of the Himalayas that travels through the Karakoram Mountains in far northeastern Afghanistan and the Pamir Mountains to reach eastern Tibet.

Relatively speaking, the “Roof of the World” is composed of rich mountain valleys that house the majority of the highest summits, which are located in the east. The Hindu Kush finishes at the west-central highlands, giving rise to the Turkestan Plains and the Sistan Basin, two plains that are scorching, windy deserts and rolling grasslands, respectively, in the north and southwest.

There is a tundra in the northeast and woods in the corridor that run between the provinces of Nuristan and Paktika (see East Afghan montane conifer forests, p. 260). Noshaq is the highest peak in the nation, rising 7,492 meters (24,580 feet) above sea level. At 258 meters (846 feet) above sea level, the lowest point is located in Jowzjan Province along the bank of the Amu River.

Even though the nation is home to several rivers and reservoirs, a sizable portion of it is desert. One of the driest places on Earth is the endorheic Sistan Basin. The Amu Darya springs north of the Hindu Kush, the Arghandab River flows south from the core area, and the neighboring Hari Rud flows west towards Herat.

Numerous streams that are Indus River tributaries flow to the west and south of the Hindu Kush, including the Helmand River. The Kabul River empties into the Indian Ocean after flowing eastward to the Indus. In the Hindu Kush and Pamir Mountains, Afghanistan has considerable snowfall in the winter. As the snowmelts in the spring, it finds its way into the country’s rivers, lakes, and streams.

Nonetheless, two thirds of the nation’s water supply flows into Turkmenistan, Iran, and Pakistan, its neighbors. According to a 2010 assessment, the state needs to spend more than US$2 billion on irrigation system rehabilitation in order to manage water resources effectively.

Within and surrounding the Badakhshan Province of Afghanistan, the northeastern Hindu Kush mountain range is a geologically active region where earthquakes may occur nearly yearly. They have the potential to be lethal and destructive, triggering avalanches in the winter and landslides in some areas.

A devastating 5.9 earthquake that occurred in June 2022 close to the Pakistani border claimed at least 1,150 lives and raised concerns about a serious humanitarian situation. Approximately 1,400 people lost their lives when a 6.3-magnitude earthquake occurred northwest of Herat on October 7, 2023.

Temperature

Afghanistan has a continental climate, with hot summers in the low-lying areas of the Sistan Basin in the southwest, the Jalalabad Basin in the east, and the Turkestan plains along the Amu River in the north, where temperatures average over 35 °C (95 °F) in July and can reach over 43 °C (109 °F).

The country’s central highlands, the glaciated northeast (around Nuristan), and the Wakhan Corridor experience harsh winters. Summers in the nation are typically dry, with the majority of the country’s rainfall occurring between December and April. Afghanistan’s lower regions in the north and west are the driest; the east has more precipitation.

With the exception of the Nuristan Province, which sporadically experiences summer monsoon rains, Afghanistan lies largely outside of the monsoon zone despite being close to India.

Biological Diversity

There are many different kinds of animals in Afghanistan. The high alpine tundra areas are home to brown bears, snow leopards, and Siberian tigers. Only in the northeastern Afghan area of the Wakhan Corridor do Marco Polo sheep call home.

The eastern mountain forest region is home to foxes, wolves, otters, deer, wild sheep, lynx, and other large cats. Wildlife in the semi-desert northern plains includes a variety of birds, gophers, hedgehogs, and huge predators like hyenas and jackals.

The steppe plains in the south and west are home to gazelles, wild pigs, and jackals, while the semi-desert south is home to mongooses and cheetahs. In Afghanistan’s high highlands, pheasants can be found in some areas, along with marmots and ibex. The Afghan hound is a canine breed indigenous to Afghanistan that is well-known in the West for its long hair and quick speed.

Afghanistan’s native wildlife includes the Afghan flying squirrel, Afghan snowfinch, Afghan leopard gecko, Stigmella kasyi, Vulcaniella kabulensis, Paradactylodon (also known as the “Paghman mountain salamander”), and Wheeleria parviflorellus, among other species. Among the endemic plants is Iris afghanica. Despite its generally dry environment, Afghanistan is home to a large diversity of birds, with an estimated 460 species, 235 of which breed there.

Afghanistan’s steppe grasslands are home to shrublands, short grass, perennial plants, and broadleaf trees, while the country’s forest areas are home to pine, spruce, fir, and larch trees. Small floral plants and resilient grasses make up the cooler high-elevation areas.

There are several locations that have been declared protected; three national parks are Band-e Amir, Wakhan, and Nuristan. Afghanistan ranked 15th out of 172 nations in the world with a mean score of 8.85/10 on the 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index.

Finance

Afghanistan’s purchasing power parity (PPP) GDP in 2020 was $81 billion, despite its nominal GDP of $20.1 billion. Its GDP per person is $611 nominally and $2,459 (PPP). It is still among the least developed nations in the world even though its mineral reserves are worth at least $1 trillion.

Afghanistan has historically been one of the least developed nations in the modern age due to its rugged topography and landlocked position; recent conflict and political instability further impede development. The country imports almost $7 billion worth of products but exports just $784 million, mostly fruits and nuts. It owes $2.8 billion to foreign creditors.

The GDP was mostly contributed to by the service sector (55.9%), then by agriculture (23%) and industry (21.1%).

The Afghani (AFN), which has an exchange rate of around 75 Afghanis to 1 US dollar, is the national currency and is issued by Da Afghanistan Bank. Afghanistan International Bank, New Kabul Bank, Azizi Bank, Pashtany Bank, Standard Chartered Bank, and First Micro Finance Bank are just a few of the domestic and international banks that are active in the nation.

The return of more than 5 million expats, who brought with them skills for generating wealth and entrepreneurship as well as much-needed capital to launch enterprises, is one of the primary forces behind the present economic revival.

One of the biggest sectors in Afghanistan nowadays is construction, which employs a considerable number of Afghans. The $35 billion New Kabul City next to the capital, the Aino Mena project in Kandahar, and the Ghazi Amanullah Khan Town next to Jalalabad are a few of the significant national building projects. Similar development initiatives have already started in other places, including Herat and Mazar-e-Sharif. Every year, an estimated 400,000 individuals join the workforce.

A number of small businesses and industries sprung up in various sections of the nation, bringing in money for the government and generating employment at the same time. Since 2003, changes to the business climate have led to investments in telecom totaling over $1.5 billion and the creation of over 100,000 new employment. Since Afghan carpets were the fourth most exported category of goods in 2016–17, their rising popularity has enabled several carpet merchants around the nation to expand their workforce.

Afghanistan belongs to the OIC, SAARC, ECO, and WTO. In SCO, it has observer status. In 2018, 84% of exports went to Pakistan and India, while the majority of imports originated in China, Iran, Pakistan, and Kazakhstan.

The US has blocked the Afghan central bank’s $9 billion in assets since the Taliban took over the nation in August 2021, preventing the Taliban from accessing billions of funds kept in US bank accounts.

Afghanistan’s GDP is thought to have decreased by 20% after the Taliban retook power. Following this, the Taliban’s prohibition on smuggled imports, limitations on financial activities, and UN assistance caused the Afghan economy to stabilize after months of freefall.

The Afghan economy started to show indications of recovery in 2023. Stable exchange rates, minimal inflation, steady tax collection, and an increase in export commerce have also followed this. The Afghani gained almost 9% value in comparison to the US dollar during the third quarter of 2023, making it the highest-performing currency globally.

Farming

In Afghanistan, agriculture has historically been the main industry and employs over 40% of the labor force. It is the foundation of the country’s economy. As of 2018. Pomegranates, grapes, apricots, melons, and a variety of other fresh and dry fruits are among the products of the nation’s fame. In 2010, Afghanistan emerged as the global leader in the production of cannabis. But in March 2023, Hibatullah Akhundzada issued an order outlawing the cultivation of cannabis.

The priciest spice, saffron, grows in Afghanistan, especially in the province of Herat. Saffron output has increased recently, and officials and farmers are attempting to replace poppy cultivation with this crop.

The International Taste and Quality Institute consistently named Afghanistan’s grown and produced saffron the finest in the world between 2012 and 2019. 2019 had a record high in production (19,469 kg of saffron), with a kilogram selling for between $634 and $1147 locally.

In the 2010s, the availability of inexpensive solar electricity to pump water and inexpensive diesel-powered water pumps that were brought from China and Pakistan led to an increase in agricultural and population in the southern Afghan desert provinces of Kandahar, Helmand, and Nimruz.

Although there is a limited supply of water, wells have been steadily deeper. The main crop, opium, was under attack in 2022 from the newly formed Taliban regime, which was methodically stopping water pumping in order to reduce opium output.

According to a 2023 assessment, Taliban operations to prohibit the crop’s usage for opium caused poppy planting in southern Afghanistan to decrease by more than 80%. This includes the Helmand Province’s opium growth being reduced by 99%.

According to a United Nations study dated November 2023, poppy production in Afghanistan fell by more than 95% overall, distancing the country from its position as the world’s leading producer of opium.

Mining

Coal, copper, iron ore, lithium, uranium, rare earth elements, chromite, gold, zinc, talc, barite, sulfur, lead, marble, precious and semi-precious stones, natural gas, and petroleum are among the nation’s natural resources. Government authorities from the US and Afghanistan calculated in 2010 that the undeveloped mineral resources discovered in 2007 by the US Geological Survey were worth at least $1 trillion.

According to Michael E. O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institution, Afghanistan’s GDP would treble and it would be able to sustainably cover its essential requirements if its mineral riches produced an annual income of around $10 billion.

In 2006, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) calculated that the average amount of crude oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids in northern Afghanistan were 460 million m3 (2.9 billion bbl), 440 billion m3 (15.7 trillion cu ft), and 67 billion L (562 million US bbl), respectively. Afghanistan and China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) inked an oil exploration agreement in 2011 for the development of three oil sites north of the Amu Darya River.

Significant reserves of lithium, copper, gold, coal, iron ore, and other minerals are found throughout the nation. One million rare earth elements (980,000 long tons; 1,100,000 short tons) may be found in the Khanashin carbonatite in Helmand Province.

The China Metallurgical Group paid $3 billion for a 30-year lease on the Aynak copper mine in 2007, making it the largest private commercial venture and foreign investment in Afghanistan’s history.

The massive Hajigak iron ore deposit in central Afghanistan is to be mined by the state-run Steel Authority of India. Thirty percent of the nation’s undeveloped mineral reserves are estimated by government experts to be worth at least $1 trillion.

According to a Pentagon report, Afghanistan may turn become the “Saudi Arabia of lithium,” and one officer predicted that “this will become the backbone of the Afghan economy.” The 21 million tons of lithium deposits may be equivalent to those of Bolivia, which is thought to have the greatest lithium reserves at the moment. Bauxite and cobalt deposits are two other major ones.

Afghanistan has less access to biocapacity than the global average. Afghanistan’s biocapacity per person was 0.43 global hectares in 2016, far lower than the worldwide average of 1.6 global hectares per person. Afghanistan’s ecological footprint of consumption in 2016 was 0.73 global hectares per person or biocapacity. This indicates that their biocapacity usage is somewhat less than double that of Afghanistan. Afghanistan is now experiencing a shortage of biocapacity.

The provinces of Herat, Ghor, Logar, and Takhar are the targets of $6.5 billion in mining contracts that the Taliban inked in September 2023. The contracts cover the extraction of gold, iron, lead, and zinc.

Power

The World Bank reports that in 2018, 98% of rural residents had access to electricity, up from 28% in 2008. In total, the percentage is 98.7%. Afghanistan generates 1,400 megawatts of energy as of 2016, however, it still imports most of its electricity through transmission lines from Iran and the Central Asian republics.

Due in part to the abundance of rivers and streams that originate in the highlands, hydropower generates the bulk of the world’s electricity. But energy isn’t always dependable, and blackouts sometimes occur—even in Kabul.

A growing number of wind, solar, and biomass power facilities have been built in recent years. The Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline and the CASA-1000 project, which would transfer energy from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, are now under development.

The Afghanistan Electricity Company, or Da Afghanistan Breshna Sherkat, is in charge of managing power.

The Sardeh Band Dam, Dahla Dam, and Kajaki Dam are notable dams.

Travel

Because of security concerns, Afghanistan’s tourism industry is tiny. Still, as of 2016, about 20,000 international visitors come to the nation each year. The gorgeous Bamyan Valley, which has lakes, canyons, and historical monuments, is particularly significant for both domestic and foreign tourists.

This is partly because it is located in a secure location away from insurgent activities. Fewer people travel to and hike in places like the Wakhan Valley, which is home to some of the most isolated people on Earth. Afghanistan became a well-liked destination for many Europeans and Americans traveling the well-known hippie path starting in the late 1960s.

The path left Iran and passed through several Afghan provinces and cities, including as Herat, Kandahar, and Kabul, before entering northern India, northern Pakistan, and Nepal. The year 1977 had a high in tourism, just before military war and political unrest began.

Along with Bamyan city, Ghazni has been named the Islamic Cultural Capital and the South Asia Cultural Capital in recent years due to its rich history and historical landmarks. Other ancient cities are Zaranj, Balkh, Herat, and Kandahar.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Minaret of Jam is located in the Hari River valley. The Shrine of the Cloak in Kandahar, the first capital of Afghanistan and a city built by Alexander the Great, is home to a cloak said to have been worn by the prophet Muhammad.

Recently refurbished, the fortress of Alexander is a famous sight in the western city of Herat. The Shrine of Ali is located in the nation’s north and is frequently cited as the site of Ali’s burial.

Numerous Buddhist, Bactrian Greek, and early Islamic artifacts may be found at the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul. The museum was severely damaged during the civil war, but since the early 2000s, it has been gradually restored.

Unexpectedly, since the Taliban took power, Afghanistan’s tourist industry has grown. Due to the Taliban’s active efforts, the number of tourists increased from 691 in 2021 to 2,300 in 2022. From 2022 to 2023, there was a notable surge of over 120% in the number of tourists, with estimates ranging from 7,000 to 10,000. The number of tourists reached around 5,200. However, ISIS-K, which was accountable for assaults on tourists including the 2024 Bamyan shooting, poses a threat to this.

Conversation

Afghan Telecom, Afghan Wireless, Etisalat, MTN Group, and Roshan are the companies that offer telecommunication services in Afghanistan. Millions of phone, internet, and television users are served by the nation’s own space satellite, Afghansat 1.

After years of civil conflict, the telecommunications sector was almost nonexistent by 2001. However, by 2016, it had grown to be a $2 billion business with 5 million internet users and 22 million mobile phone customers. Nationwide, the industry employs at least 120,000 people.

Transport

Afghanistan’s topography has long made transportation between its many regions challenging. Highway 1, also known as the “Ring Road,” is the main thoroughfare in Afghanistan. It stretches 2,210 kilometers (1,370 mi) and links five major cities, including Kabul, Ghazni, Kandahar, Herat, and Mazar-i-Sharif. It also has spurs that connect Kunduz and Jalalabad, as well as several border crossings, and it skirts the Hindu Kush mountains.

The Ring Road is vital to the economy and to both local and foreign trade. The Salang Tunnel, which connected northern and southern Afghanistan and made passage over the Hindu Kush mountain range easier, is an important part of the Ring Road.

It was finished in 1964. There isn’t another land route that links the Indian subcontinent with Central Asia. There are a number of mountain passes that connect different parts of the Hindu Kush.

On Afghan roads and highways, notably the Kabul–Kandahar and Kabul–Jalalabad Roads, serious traffic accidents are frequent occurrences. In Afghanistan, bus travel is still risky because of insurgent activity.

Both the state airline, Ariana Afghan Airlines, and the private firm Kam Air offer air travel in Afghanistan. Flights into and out of the nation are also offered by airlines from several nations. Turkish Airlines, Pakistan International Airlines, Iran Aseman Airlines, Emirates, Gulf Air, and Air India are a few of these.

Hamid Karzai International Airport (previously Kabul International Airport), Kandahar International Airport, Herat International Airport, and Mazar-e Sharif International Airport are the four international airports in the nation. There are forty-three, including domestic airports. A significant military airstrip is Bagram Air Base.

Three rail links connect the nation: a 75-kilometer (47-mile) line that runs from Mazar-i-Sharif to the border with Uzbekistan; a 10-kilometer (6.2-mile) line that runs from Toraghundi to the border with Turkmenistan (where it continues as part of Turkmen Railways); and a short link that runs from Aqina across the Turkmen border to Kerki, with plans to extend it further across Afghanistan.

There is no passenger service on these lines; they are exclusively utilized for freight. As of 2019, work was underway to create a rail line that would carry both people and freight between Khaf, Iran, and Herat, western Afghanistan. Approximately 78 miles (125 km) of the line will be on the Afghan side.

The number of private vehicles owned has significantly grown during the early 2000s. Both auto rickshaws and vehicles make up taxis, which are yellow in color. Donkeys, mules, or horses are frequently used by the peasants in rural Afghanistan to move or carry things. Kochi nomads are the main users of camels. Bicycles are widely used in Afghanistan.

Characteristics

The Afghanistan Statistics and Information Authority stated that 32.9 million people lived in Afghanistan as of 2019, whereas the UN says that it is closer to 38.0 million. The population as a whole was estimated to be 15.5 million in 1979.

Of them, around 23.9% are city dwellers, 71.4% are country people, and the remaining 4.7% are nomads. About 3 million more Afghans, the majority of whom were born and nurtured in neighboring Pakistan and Iran, are being temporarily accommodated there. Afghanistan kept the status of being the world’s greatest refugee-producing nation for 32 years as of 2013.]

With a population growth rate of 2.37%, it is now among the highest outside of Africa. If present population trends continue, it is predicted that its population will reach 82 million by 2050. Afghanistan’s population grew gradually until the 1980s when a civil conflict forced millions of people to escape to neighboring Pakistan.

Since then, millions have returned, and the nation has the highest fertility rate outside of Africa due in part to the war conditions. Although Afghanistan has the lowest life expectancy of any nation outside of Africa, its healthcare system has improved after the year 2000, leading to decreases in neonatal mortality and rises in life expectancy.

This contributed to the 2000s’ tremendous population expansion, which has just now begun to slow down, along with other causes including the repatriation of refugees. In 2008, the Gini coefficient was 27.8.

City Living

The CIA World Factbook projected that by 2020, 26% of the population will be urbanized. The only countries in Asia where this number is greater are Cambodia, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. It is among the lowest globally.

Due to the influx of rural migrants, internally displaced persons, and returning refugees from Pakistan and Iran during 2001, urbanization has risen dramatically, especially in the capital city of Kabul. Afghanistan’s urbanization differs from other urbanization patterns in that it is concentrated in a small number of cities.

Kabul, the nation’s capital and only city with more than a million inhabitants, is situated in the east of the nation. The other major cities are mostly found in the “ring” that encircles the Central Highlands: Herat to the west, Kandahar to the south, Mazar-i-Sharif to the north, Kunduz to the east, and Jalalabad to the east.

Languages and Ethnicity

There are several ethnolinguistic groupings among Afghans. The largest ethnic group in the nation is the Pashtuns, who make up 42% of the population, followed by the Tajiks, who make up 27%, according to research data published by many institutes in 2019. Hazaras and Uzbeks make up the other two largest ethnic groups, each with 9% of the total. Ten further recognized ethnic groups are individually represented in the Afghan National Anthem.

Afghanistan’s official languages are Dari and Pashto, although bilingualism is highly prevalent. Dari, sometimes known as Eastern Persian since it is a dialect of Persian that is mutually intelligible with it (and is frequently referred to as “Farsi” by some Afghans, much like in Iran), serves as the primary language in Kabul and a large portion of the country’s northwest and north.

Any ethnic group who are native Dari speakers is occasionally referred to as Farsiwans. The Pashtuns’ native dialect is Pashto, however many of them can also speak Dari well, and few non-Pashtuns can also speak Pashto well. Dari continued to be the official language of the government and bureaucracy of Afghanistan, even after the Pashtuns had dominated governance for generations.

As per the CIA World Factbook, 78% of people speak Dari Persian (L1 + L2), which serves as the common language. In contrast, 50% of people speak Pashto, 10% speak Uzbek, 5% speak English, 2% speak Turkmen, 2% speak Urdu, 1% speak Pashayi, 1% speak Nuristani, 1% speak Arabic, and 1% speak Balochi (2021 est).

The most commonly spoken languages are shown in the data; shares add up to more than 100% since respondents were permitted to choose more than one language and because bilingualism is common in the nation. Smaller regional languages like Turkmen, Uzbek, Balochi, Pashayi, and Nuristani are among them.

When it comes to foreign languages, a large portion of the population can speak or comprehend Hindustani (Urdu-Hindi), in part because of the popularity of Bollywood films and the return of Afghan refugees from Pakistan. A portion of the populace can also understand English, which has grown in popularity during the 2000s. After learning Russian in public schools in the 1980s, some Afghans are still proficient in the language.

Religion

In 2009, the CIA calculated that 99.7% of Afghans were Muslims, with the majority believed to follow the Sunni Hanafi school of thought. Up to 90% of people identify as Sunni, 7% as Shia, and 3% as non-denominational, according to Pew Research Center. Estimates from the CIA Factbook range from 15% to 89.7% Sunni.

In addition, there are gurdwaras and mandirs in Kabul, Jalalabad, Ghazni, and Kandahar, among other significant cities, where Afghan Sikhs and Hindus may be found. In September 2021, Deutsche Welle reported that 250 people were still in the nation after 67 were relocated to India.

In Afghanistan, there was a small Jewish population that was concentrated in Herat and Kabul. This little group was forced to relocate over time as a result of decades of conflict and religious persecution. With the notable exception of Zablon Simintov, who was born in Herat, almost the whole community had left for Israel and the US before the end of the 20th century.

He stayed for many years, tending to the last surviving Afghan synagogue. Following the second Taliban takeover, he departed for the United States. The likely last Jewish person in Afghanistan has now been identified as a lady who departed not long after him.

There are no official churches in Afghanistan, and the 500–8,000 Christians who follow their faith do so in secret because of strong cultural resistance.

Learning

The Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Higher Education are in charge of overseeing education in Afghanistan. There are around 9 million kids in the nation and more than 16,000 schools. Approximately 60% of them are men and 40% are women. Still, female students and teachers are not allowed to return to secondary schools under the current system.

There are more than 174,000 students enrolled in various colleges around the nation. Among these, women make up around 21%. According to Ghulam Farooq Wardak, the former minister of education, 8,000 new schools must be built in order to educate the remaining children who are not receiving formal education. In 2018, 43.02% of people over the age of 15 were literate (males 55.48% and females 29.81%).

The American University of Afghanistan (AUAF) and Kabul University (KU), both of which are situated in Kabul, are the two best institutions in Afghanistan. The National Military Academy of Afghanistan was a four-year military training center designed to produce officers for the Afghan Armed Forces.

It was fashioned after the US Military Academy at West Point. In Kabul, the Afghan Defense University was built next to Qargha. Kandahar University in the south, Herat University in the northwest, Balkh University and Kunduz University in the north, Nangarhar University and Khost University in the east are some of the prominent institutions that are located outside of Kabul.

When the Taliban took back control of the nation in 2021, it was unknown how long female education would last. Following a period of closure, announcements for the reopening of secondary education were made in March 2022.

But the order was reversed just before reopening, so older girls’ schools stayed closed. Six provinces—Balkh, Kunduz, Jowzjan, Sar-I-Pul, Faryab, and the Day Kundi—allow girl’s schools for grades 6 and beyond despite the prohibition. The UN was conducting investigations in December 2023 into the allegation that religious institutions in Afghanistan permitted girls of all ages to attend classes.

Wellness

Afghanistan is the fifteenth least developed nation in the world based on the Human Development Index. It is expected that the typical person will live for about 60 years. The nation’s infant mortality rate ranges from 66 to 112.8 deaths per 1,000 live births, while the maternal mortality rate is 396 deaths per 100,000 live births.

Before 2020, the infant mortality rate is expected to be reduced to 400 per 100,000 live births by the Ministry of Public Health. There are currently over 3,000 midwives in the nation, and an additional 300–400 are trained annually.

Afghanistan has more than 100 hospitals, with Kabul offering the most cutting-edge medical care. The top children’s hospitals in the nation are the Indira Gandhi Children’s Hospital in Kabul and the French Medical Institute for Children. The Jinnah Hospital and Jamhuriat Hospital are a couple of the other top hospitals in Kabul. Despite this, a large number of Afghans seek cutting-edge medical care in Pakistan and India.

According to a 2006 estimate, about 60% of Afghans reside close to the closest medical facility—a two-hour walk. Afghanistan has a high rate of disability as a result of the prolonged conflict. According to a recent research, over 80,000 individuals are limbless. Non-governmental organizations that support orphans in conjunction with governmental entities include Save the Children and Mahboba’s Promise.

Traditions

Afghans share cultural traits as well as those that are unique to their respective areas, each of which has developed in part due to the physical barriers that separate the nation. Afghan society is centered around the family, which is frequently led by a patriarch.

People in the southern and eastern regions adhere to Pashtunwali, or the Pashtun way, in order to live in accordance with Pashtun culture. The main principles of Pashtunwali are hospitality, giving safety to those in need, and taking retribution for bloodshed. The Pashtuns have strong ties to the Iranian Plateau and Central Asian cultures. The Turkic and Persian cultures are those of the surviving Afghans.

In a process known as Pashtunization, certain non-Pashtuns who coexist with Pashtuns have accepted Pashtunwali, whilst some Pashtuns have undergone Persianization. The cultures of Pakistan and Iran have had a lasting impact on people who have been there for the past thirty years. It is well known that Afghans have strong religious beliefs.

Pashtuns in particular are known for their strong sense of tribal unity and great regard for individual honor among Afghans. There are two to three million nomads in Afghanistan, as well as a variety of tribes. Although pre-Islamic customs still exist, Afghan culture is firmly rooted in Islam. The legal age of marriage is sixteen, however child marriage is common. In Afghan society, marrying one’s parallel cousin is the most desirable union, and the husband is sometimes required to pay a bride price.

Families usually live in mudbrick homes in the villages, or in complexes with stone or mudbrick walls. Traditionally, a village would have a headman (malik), a master in charge of distributing water (mirab), and a religious instructor (mullah). Traditionally, women would accompany males in the fields to labor during harvest.

A quarter or more of the populace are kochis, or nomadic people. Nomads frequently purchase products from communities, including tea, wheat, and kerosene, while villagers purchase wool and milk from the nomads as they pass by.

The most common kinds of Afghan clothes for both men and women are shalwar kameez, particularly khet partug, and perahan tunban. Normally, women would cover their heads with chadors; but, some, usually from very orthodox groups, wear burqas, which cover the entire body.

Although some Pashtun women wore these even before Islam arrived in the area, the Taliban required women to wear them when they were in control. An additional common garment is the chapan, which serves as a coat. A hat known as a “karakul” is fashioned from the fleece of a particular local sheep breed.

Former Afghan rulers were fond of it, and when President Hamid Karzai wore it on a daily basis in the 21st century, it gained widespread recognition. Another traditional hat from the country’s far east is the pakol, which was made famous by guerilla commander Ahmad Shah Massoud. The origins of the Mazari hat are in northern Afghanistan.

Buildings

The country has a rich past that has persisted in the forms of many languages, monuments, and modern cultures. Afghanistan is home to numerous artifacts from all historical periods, such as Islamic minarets, monasteries, monuments, temples, and stupas from Buddhism and Greek culture.

The most well-known are the Blue Mosque, the Great Mosque of Herat, the Chil Zena, the Qala-i Bost near Lashkargah, the Blue Mosque, and the ancient Greek city of Ai-Khanoum. However, as a result of the civil conflicts, many of its ancient sites have suffered damage in more recent times. The Taliban demolished the two well-known Buddhas of Bamiyan because they believed them to be idols.

Although it is uncommon, European-style architecture may be found in Afghanistan due to the lack of colonization throughout the modern era. Two examples of such buildings are the 1920s-century Victory Arch in Paghman and the Darul Aman Palace in Kabul. Deep into India, Afghan architecture may be seen in places like Agra and the mausoleum of Sher Shah Suri, the Afghan Emperor of India.]

Ceramics and Art

In Afghanistan, carpet weaving has long been a tradition, and many of these are still manufactured by tribal and nomadic people today. For millennia, women have been the primary producers of carpets in this area. A subset of Afghan carpets known as “war rugs” were made with motifs that symbolized the suffering and agony brought about by the battle following the start of the Soviet-Afghan War.

Afghanistan has been producing pottery for thousands of years. Particularly well-known for its distinctive turquoise and green pottery, and with centuries-old making techniques, is the town of Istalif, north of Kabul. A large portion of the lapis lazuli stones that were earthed in present-day Afghanistan were utilized as cobalt blue in Chinese porcelain, which was then used in prehistoric Mesopotamia and Turkey.

Afghanistan has a rich artistic heritage; its cave murals are the oldest known examples of oil painting in the world. Gandhara Art is a prominent art form that emerged in Afghanistan and eastern Pakistan around the first and seventh centuries CE as a result of the blending of Buddhist and Greco-Roman art.

The Persian miniature style became more popular in later times; among the most renowned miniature artists of the Timurid and early Safavid eras was Kamaleddin Behzad of Herat. The country started utilizing Western artistic styles in the 1900s. During the 20th century, Abdul Ghafoor Breshna was a well-known painter and sketch artist from Kabul, Afghanistan.

Every province has unique qualities that are unique to its rug-making industry. The bride’s weaving abilities determine the cost of the wedding ceremony and bride in certain of the northwest’s Turkic-populated districts.

Books

Afghan culture cherishes the poetry of the old Persian and Pashto languages. Since poetry has become so ingrained in the local culture, it has long been one of the main foundations of education in the area. Landay is the name of one of the poetry forms. The horrific monsters known as Divs are a common motif in Afghan mythology and folklore. Thursdays are known as “poetry night” in the city of Herat, where men, women, and kids get together to perform poems from antiquity and the present day.

Three mystical writers—Khwaja Abdullah Ansari of Herat, a great mystic and Sufi saint in the eleventh century; Sanai of Ghazni, a writer of mystical poems in the twelfth century; and Rumi of Balkh, a 13th-century poet regarded as the greatest mystical poet in the Muslim world—are regarded as true national glories, albeit Iran claims them with equal ardor.

Despite being statistically impressive and seeing significant development in the past century, Afghan Pashto literature has always been fundamentally local in nature, drawing inspiration from both Persian and Indian literature that are next to it. Since the latter part of the nineteenth century, both major literatures have demonstrated a sensitivity to European genres, movements, and stylistic elements.

The national poet is regarded as 17th-century Khushal Khan Khattak. Rabi’a Balkhi, Jami, Rahman Baba, Khalilullah Khalili, and Parween Pazhwak are a few other well-known poets.

Music

Afghan classical music uses Hindustani terminology and ideas, such as raga, and has historical ties to Indian classical music. Poetic music (ghazal) and instruments like the Indian tabla, sitar, and harmonium, as well as regional instruments like the zerbaghali and dayereh, and tanbur, which are also well-known in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Middle East, are genres of this kind of music. The Indian sarod instrument was inspired by the rubab, the nation’s native instrument. Classical musicians such as Sarban and Ustad Sarahang are well-known.

Pop music emerged in the 1950s thanks to Radio Kabul and had a significant impact on societal transformation. Around this period, female musicians began to emerge as well; Mermon Parwin was the first.

Probably the most well-known performer in this genre was Ahmad Zahir, who blended several genres and is still remembered for his soulful voice and insightful lyrics even after his passing in 1979. A few more prominent figures in Afghan music, whether it be traditional or contemporary, include Nashenas, Ubaidullah Jan, Mahwash, Ahmad Wali, Farhad Darya, and Naghma.